Overview

Despite anticipated positive impacts to the Nigerian economy, the Lagos-Ibadan railway has failed to generate positive economic spillover. Nigeria will need additional infrastructure investment to meet the promise of positive economic development.

Activity

This report will focus on economic spillover created by the Lagos-Ibadan railway to the Nigerian economy. To determine the status of development, the report will analyze railway connectivity to industrial bases. GEOINT will enhance economic data to show the connections.

Introduction

Unveiled by China in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative is currently the world's most ambitious economic development program. Rooted in Beijing's desire to become a leader in global development, BRI aspires to promote economic development through infrastructure investment in over 68 countries whose economies constitute a combined 40 percent of global GDP. The program has invested an estimated $200 billion in partner countries globally, raising hopes that infrastructure mega-projects, such as railway investments, will stimulate economic growth in the developing world.1

In a number of countries, this has been the case. In Ethiopia, for example, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) serves as Beijing's flagship BRI project, successfully linking land-locked Ethiopia to Djibouti's seaports and global maritime shipping lanes. Through the project, the Ethiopian government connected existing fragmented industrial bases, such as dry ports and industrial parks, creating a connected infrastructure to encourage economic growth in Ethiopia. While the project has indeed brought about modest positive impacts on the Ethiopian economy, the economic outcome is not as successful as anticipated, drawing into question the validity of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway as a model for African infrastructure development.

In Nigeria, a new high-capacity, standard-gauge rail line is scheduled to begin operation in May 2019, linking Lagos, Nigeria's largest city, to the inland city of Ibadan, a non-oil industrial hub. The Lagos-Ibadan Railway shares several key characteristics and policy goals with the Addis Ababa-Djibouti line in East Africa; the Nigerian government plans to streamline the logistics by connecting the railway to major industrial cities and hence encourages export from different industries. However, unlike the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, the Lagos-Ibadan Railway is poorly connected with existing inland industrial bases, raising concerns over logistics efficiency and, ultimately, the potential for the Lagos-Ibadan Railway to replicate the modest economic gains attributed to the Addis Ababa-Djibouti line. Our research shows Nigeria will need additional infrastructure/logistical capacity before the BRI investment can contribute to the economic development of the Nigerian economy.2

Given the unprecedented scope of BRI and its potential geopolitical ramifications, the Chinese economic development model has attracted both enthusiastic fans and strident critics. However, while volumes are being written about the initiative, much of the conversation is based on opinion and subjective analysis. In the absence of cohesive data about financing terms, project details, and economic development outcomes of BRI projects, fact-based approaches to evaluating the BRI are badly needed.

Methodology

To this end, satellite imagery provides unique insights and objective evidence of BRI projects unfolding on the ground in real time. As the Lagos-Ibadan SGR approaches completion in May 2019, satellite imagery analysis is a critical tool in examining and projecting the railway's developmental impacts. Imagery analysis is in turn supported by additional sources, such as project documents, macroeconomic data, expert interviews, and other traditional research tools. In this way, we aim to gain new insights into BRI projects and the future value of similar assets that have cost billions of dollars to construct.

Current State of Nigerian Railway Network

Railways have played a critical role in economic development since the 19th century, transporting not only passengers but also high-value goods and services.3 Nigeria's existing narrow-gauge railway network, inherited from the British colonial period, is outdated and insufficient to handle modern freight and passenger volume. Moreover, the Nigerian government has not adequately maintained the existing rail system. The deteriorating railway has decreased transportation efficiency, resulting in increased transport costs and travel delays, contributing to hindered economic growth.

The Lagos-Ibadan line is a significant step in the Nigerian government's goal of a modernized rail network. In 2012, the Nigerian government signed a construction contract for the railway with China Civil Engineering Construction Company (CCECC), a Chinese state-owned enterprise. China Export-Import (EXIM) Bank financed the $1.53 billion project cost under concessional loan terms. The new standard-gauge Lagos-Ibadan line was designed to improve logistical efficiency, increase capacity to transport passengers and freight and generate comprehensive benefits for local economies along the railway.

However, the rail project has already encountered challenges. Weather and equipment delivery delays have pushed back the railway's completion date from the original target in December 2018 to May 2019. In July 2018, construction of the Abeokuta station, an important hub between the Lagos and Ibadan, was suddenly relocated from its planned location at Trade Fair Complex to Oba New City, a six-kilometer distance apart after problematic engineering conditions were discovered. While construction delays are commonplace in complex projects, managerial complexities and construction quality play a key role in operational efficiency throughout the lifespan of a railway project.

Examination of Benchmark Case in Ethiopia

To assess the impacts of the standard-gauge Lagos-Ibadan line, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti SGR serves as a helpful benchmark. Also constructed by the CCECC, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti line has been completed and operated since January 2018. The relatively new railway project has not yet fulfilled its role as a central part of the Ethiopian economy, as Ethiopian authorities are constructing connections between existing production facilities outside of the 759 km Addis Ababa-Djibouti line to the railway, including two dry ports and five fully operational industrial parks.4-5 The Addis Ababa-Djibouti line serves as a baseline for both the potential and the pitfalls facing the Lagos-Ibadan line in Nigeria.

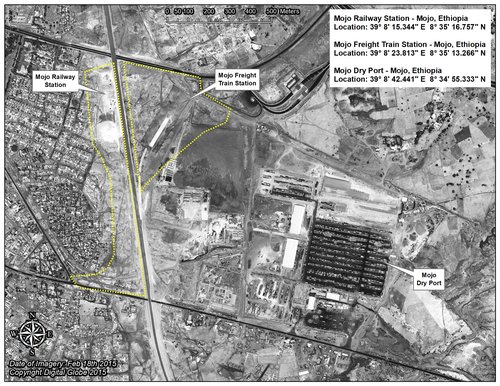

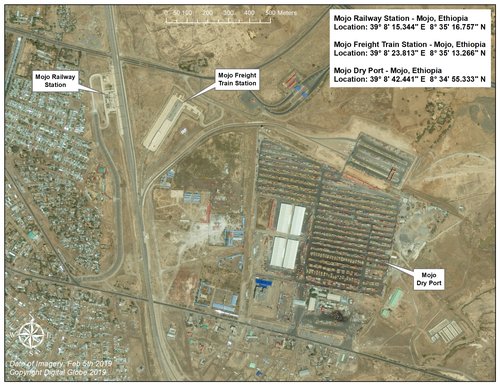

In Ethiopia, increased industrial and transport capacity has sprung up in the vicinity of railway stations. For example, an industrial park in the Ethiopian city of Adama was inaugurated in October 2018, shortly after construction of the Adama Railway Station.6 Imagery analysis confirms the expansion of the Adama Industrial Park following the completion of the nearby railway station. The park now houses two Chinese manufacturing firms and is nearing its projected goal of 25,000 local new jobs. In the city of Modjo, synergies between new railway connectivity and existing facilities are also evident, as the dry port adjacent to the new railway station already handles 74% of Ethiopia's import/export and is under expansion to increase its export capacity.7 In the city of Awasa, since its inception in 2017, the inland Hawassa Industrial Park, the largest industrial park in Ethiopia, has already generated more than $38 million in revenue between January 2017 and December 2018. Textile companies in the park have created 23,000 jobs for local Ethiopians.8 However, freight transport remains extremely expensive: roughly $2,000 per container between Hawassa and the Djibouti port, which qualifies the optimism about Ethiopia's economic development.9 To address high transportation costs, the Ethiopian government began construction of an expressway connecting Hawassa Industrial Park to Modjo dry port, a project intended to streamline transport efficiency and simplify import and export processes. As illustrated by the Hawassa Industrial Park case, it is clear that rail infrastructure alone cannot support economic development without a coordinated plan connecting the railway to dry ports, industrial parks, and other critical infrastructure.

The opening of the Adama Industrial Park after the construction of the new Adama railway station.

Active Mojdo dry port had been expanded further with the opening of a new Modjo railway station.

Fully completed Hawassa Industrial Park. Connected to an expressway that runs to the city of Modjo.

The Nigerian Case

The Addis Ababa-Djibouti case suggests that the potential of the Lagos-Ibadan SGR to support economic development will depend on the quality of its integration with regional industrial facilities. However, the manufacturing build-outs spotted in Ethiopia, and the jobs they have created are not yet visible along the Lagos-Ibadan SGR. Ambitions for dual passenger and freight have not been accompanied by connections to critical industrial assets along the Lagos-Ibadan line. Several key manufacturing plants including a British-American Tobacco processing facility, a Nestle production plant, and Dangote Cement facility as well as the Ogun-Guangdong Special Economic Zone (SEZ) are within a few dozen miles of the Lagos-Ibadan line. However, no plans have been announced to connect these facilities to the rail line, casting doubt on whether proximity to the railway will enable efficiency gains for the firms in question.

Attempts to identify instances of significant spillover activity that can be attributed to the construction of the Lagos-Ibadan line yielded few results. For example, while the expansion of a railyard in Laguna Station in Abeokuta is evident from imagery analysis, activity beyond the railyard is limited to scattered residential and commercial developments. Examination of the railway's path along the Lagos-Ibadan corridor reveals little development that is comparable to Ethiopia's Adama Industrial Park, or similar industrial assets.

Fully completed Laguna railyard near Abeokuta displays a few residential developments along with the railway station.

While the outlook for immediate economic development along the Lagos-Ibadan line is insignificant as illustrated by few residential and commercial build-outs around the railway station, some planned features of the railway raise hopes for future inland business opportunities. At present, inland producers face numerous challenges seeking to transport export goods to international markets, including cumbersome custom clearance procedures, high inland transport costs, and perennial congestion at the seaports.10 To address this issue, the Ibadan government announced a plan to add a dry port at the end of the Lagos-Ibadan SGR to facilitate expedited custom procedures and reduce congestion at Lagos ports in November 2018. A dry port is an inland intermodal terminal, facilitating a bidirectional flow of goods from inland areas to seaports by way of road or rail transfer.

The planned Ibadan dry port would serve as a consolidation point, receiving cargo from Lagos ports and preparing goods from inland producers to be transferred to the coast. Notably, the planned port will also be a customs clearance spot for both export and import cargoes which would reduce the cargos processing time in Lagos.11 A well-functioning dry port in Ibadan would have the potential to serve as a pressure valve for congested port capacity in Lagos since goods could be transported directly up the rail line before undergoing customs processes in Ibadan. Conversely, exporters might enjoy expedited processing and transfer of goods from Ibadan to global destinations.

However, potential gains offered by the dry port depend on timely completion of both the Lagos-Ibadan SGR and an operationally sound and bureaucratically sanctioned dry port. Recent imagery shows that Ibadan Station is far from complete, suggesting that the plans for the dry port, construction has not yet begun, may be delayed indefinitely. With the slow progress of railway construction and history of deferred deadlines by the Nigerian government, it is unlikely that the Nigerian government will pursue construction of the dry port any time soon.

Although the Lagos-Ibadan SGR planners aspired to improve logistics and transport efficiency, poor connectivity between the rail line and existing industrial facilities, and a lack of blueprints for new industrial parks cast doubt on the prospect of local economic benefits along the Lagos-Ibadan corridor.

Conclusion

It is no coincidence that railways are one of the most enduring symbols of industrialization and economic development. Throughout its many years of operation, the Lagos-Ibadan SGR will undoubtedly play an extended role in local economies along the rail line. However, high hopes for the future cannot displace the railway's inauspicious start in cultivating interconnections and physical development along the line.

With a lack of infrastructure connecting industrial parks and facilities to the railway, along with unclear plans for a capacity-increasing dry port, economic spillover attributable to the Lagos-Ibadan SGR is modest at best. A handful of scattered residential developments along the trunk line cannot support a message of regional stimulus to the Nigerian economy. The future of the Ibadan dry port and associated optimism for the local economy will depend mainly on a coordinated policy response from the Nigerian government. In a separate Tearline article, we examine the intermodal connection between Lagos-Ibadan Railway and Lagos ports, exploring the potential and pitfalls for efficiency gains at Lagos ports, and the implications this may have for a diversified Nigerian export economy.

Importantly, closing gaps in critical infrastructure remains at the top of the agenda for Nigeria and other sub-Saharan African countries. However, productive increases drawn from infrastructure development depend heavily on complementary policy support. In this sense, BRI infrastructure investment is not a quick fix, providing only one half of the equation for economic success. The future of the Lagos-Ibadan line, and the success of the BRI projects generally, can be fulfilled only if integrated into the broader framework of coordinated development policy.

References

- Council on Foreign Relations. "China's Massive Belt and Road Initiative" February 21, 2019. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative

- Emmanuel Ukoh. The Lagos-Ibadan rail: An Economic Frontier. February 13, 2019. https://www.von.gov.ng/the-lagos-ibadan-rail-an-economic-front-tier/

- Council on Foreign Relations. "All Aboard Nigeria Railways" April 9, 2013. https://www.cfr.org/blog/all-aboard-nigeria-railways

- African Press Agency. "Ethiopia to construction five dry ports - official" November 6, 2017.http://apanews.net/mobile/NewsInterieure_EN.html?id=4884156

- Industrial Parks Development Corporation. Our Other Parks http://www.ipdc.gov.et/index.php/en/industrial-parks/our-other-parks

- Ethiopia Broadcasting Organization. Adama Industrial Park Inaugurated October 8, 2018. http://www.ebc.et/web/news-en/-/adama-industrial-park-inaugurated

- Ethiopian Press Agency. "Modjo dry port: Nation's major import-export destination key to save foreign currency" February 5, 2019.https://press.et/english/?p=2200#

- All Africa. Ethiopia: Hawassa Industrial Park Generates U.S.$38m December 29, 2018.https://allafrica.com/stories/201901020119.html

- The Guardian. Park Life. Workers Struggle to Make Ends Meet at Ethiopias $250 m Industrial Zone December 5, 2017.https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/dec/05/ethiopia-industrial-park-government-investment-boost-economy-low-wages

- Paul Garnwa, Anthony Beresford, and Stephen Pettit. "Dry Ports: A Comparative Study of the United Kingdom and Nigeria" No. 78, 2099. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/bulletin78_Article-2.pdf

- Yusuf Babalola. "Proposed $134 million Ibadan Port Will End Apapa Traffic" April 1, 2019. https://leadership.ng/2019/04/01/proposed-134m-Ibadan-port-will-end-apapa-traffic/

Look Ahead

The construction of the SGR is part of Nigeria's broader development framework. Anticipating its completion in May 2019, it is important to take notice of recent developments along the railway.

Things to Watch

- Possible upstream supply chain and manufacturing production effects of Lagos-Ibadan SGR upon its immediate completion.

- Changes in planned stations.

- The new location of the planned station in Ebute-Metta and its connectivity to the Port of Lagos.

About The Authors

Columbia School of International and Public Affairs 2019

Columbia School of International and Public Affairs 2019

Columbia School of International and Public Affairs 2019

Columbia School of International and Public Affairs 2019

Columbia School of International and Public Affairs 2019

Columbia School of International and Public Affairs 2019

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.