- NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

Wings of Violence: Locating the Source and Method of Aerial Attacks on Civilians and Civil Infrastructure in North-Central Myanmar

Myanmar has been embroiled in violence since the military staged a coup d'état overthrowing the government in 2021. The country's air force has waged deliberate campaigns targeting rebel groups and civilians alike throughout the country, striking hospitals, schools, and religious buildings. In the years preceding civil war, the Myanmar Air Force (MAF) improved its aerial strike capabilities by upgrading infrastructure and procuring additional offensive aircraft, according to regional media.[1]

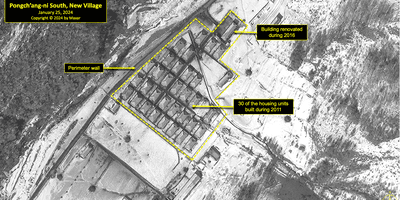

North Korea's Political Prison Camp, Kwan-li-so No. 18

Although North Korea officially announced the closure of Kwan-li-so No. 18 in 2006, commercial satellite imagery analysis indicates that the camp has not been completely razed. Imagery analysis further indicates that the remaining facility, whether officially designated as such or not, is a large and active detention facility.

North Korea's Political Prison Camp, Kwan-li-so No. 25

Based on an analysis of key physical features, political prison camp (kwan-li-so) no. 25, established around 1968, remains an operational prison. The prison camp is well maintained by North Korean standards. The estimated population, based on imagery analysis of the compound, is between 2,500 and 5,000 prisoners.

Tracking the Relocation of Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh: A Nighttime Lighting Approach

This report uses nighttime lighting data to track the relocation of Rohingya refugees from the Cox's Bazaar region of Bangladesh to Bhasan Char, a 'floating island' in the Bay of Bengal built by the Government of Bangladesh to house roughly 100,000 refugees. Constructed on reclaimed land in a monsoon, cyclone, and tsunami-prone region, Bhasan Char poses not only humanitarian challenges, but physical and human rights challenges as the Rohingya become isolated from the mainland.

Part 1: Investigating the Growth of Detention Facilities in Xinjiang Using Nighttime Lighting

A growing body of research has systematically documented Chinese efforts to imprison, detain, and re-educate ethnic Uyghur and minority groups throughout its western Xinjiang province. In this three-part investigation, RAND researchers explore new data on nighttime lighting in Xinjiang to offer new, empirical insights into China's efforts to reeducate, detain, and imprison its Uyghur and ethnic minority populations across Xinjiang.

Part 2: Have Any of Xinjiang's Detention Facilities Closed?

This report, the second in a three-part series, employs a novel empirical approach to systematically assess the current operating status of known detention facilities in Xinjiang using nighttime lighting. This analysis provides new, empirical evidence to suggest that the overwhelming majority of detention facilities in Xinjiang remain active, operational, and in many cases, still under construction – despite Chinese claims to the contrary.

Part 3: Explaining Variation in the Growth and Decline of Detention Facilities across Xinjiang

This report, the final in our series, explores trends in the growth and decline of nighttime lighting over detention facilities across Xinjiang. It reveals evidence to suggest that long-term prisons have become a greater priority than reeducation centers, along with those located in rural areas or in areas administered by the XPCC, among other trends. Overall, this report helps chart the current trajectory of China's widespread detention of Uyghur and ethnic minority populations in the region.

Empty Lots, Green Spaces, and a Parking Lot – What Happened to the Demolished Uyghur Cemeteries?

Analysis of 48 Uyghur cemeteries in Xinjiang indicates that while many were repurposed for the reasons cited by the Chinese government, fully a third were demolished with no further development on the site.

Part 3: More "Boarding" Facilities Geolocated in Southern Xinjiang

In this third Tearline report, RAND identified 21 facilities that could be where western researchers, press accounts and professional journals indicate preschool-aged Uyghur children are schooled and often housed in Qira (Chira) County, Hotan prefecture. Some of the newly identified facilities are on the grounds of primary schools, while others were not imaged frequently enough in the last four years to determine firm construction timelines.

Part 2: Geolocating Growth of Suspect "Boarding" Facilities in Xinjiang China

RAND has identified 55 facilities suspected of housing young children the construction of which coincided with a publicly stated policy to build “boarding schools” in Xinjiang. Western researchers and press allege that Xinjiang authorities are using repurposed and newly built schools to board Uyghur youth as part of a policy of intergenerational separation.