Overview

Based on an analysis of key physical features, political prison camp (kwan-li-so) no. 25, established around 1968, remains an operational prison. The prison camp is well maintained by North Korean standards. The estimated population, based on imagery analysis of the compound, is between 2,500 and 5,000 prisoners.

The prison camp's forced labor activity consists of a combination of agricultural production and light industrial manufacturing, such as bicycles and wood products.

Activity

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) to use satellite imagery and former detainee interviews to shed light on human suffering in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK, more commonly known as North Korea) by monitoring activity at political prison facilities throughout the nation.

Facility Analysis

Location: Susŏng-dong, Ch’ŏngjin-si, Hamgyŏng-bukto (Susŏng neighborhood, Ch’ŏngjin City, North Hamgyŏng Province)

CenterPoint Coordinates: 41.834384°N, 129.725280°E

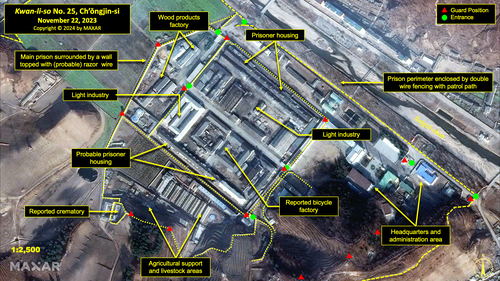

Date of Imagery Used: November 22, 2023 (Maxar)

Size of Facility: 0.98 km2 (0.38 mi2); 1,810 m by 1,240 m (1,979 yd by 1,356 yd)

Executive Summary

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former detainee interviews to shed light on human suffering in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, more commonly known as North Korea) by monitoring activity at political prison facilities throughout the nation.Previous reports in the project can be found at https://www.hrnk.org/publications/hrnk-publications.php.[1] This report provides an abbreviated update to our previous reports on a long-term political prison commonly identified by former detainees and researchers as Kwan-li-so no. 25Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., 'North Korea Camp No. 25 – Update 2' (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Nov. 29, 2016). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/ASA_HRNK_Camp25_Update2.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., 'North Korea Camp No. 25 – Update' (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Jun. 5, 2014). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Camp%2025%20Update%20Good.pdf; and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., “Satellite Imagery Shows Captives Inside Camp No. 25 in North Korea,” HRNK Insider, Aug. 8, 2018. https://www.hrnkinsider.org/2018/08/satellite-imagery-shows-captives-inside_30.html.[2] by providing details of significant activity observed between 2021 and 2023.Some interviewees and researchers have occasionally identified the facility as “Political Prison Camp 25,” “Camp 25,” or the “Susŏng-dong Kyo-hwa-so” (re-education through labor camp).[3]

For this report, HRNK analyzed commercial pan-sharpened multispectral satellite images of Kwan-li-so no. 25 and its immediate environment taken in November 2023, focusing on the following physical features.The term “high resolution” in this report refers to digital satellite images with a ground sample distance (GSD) of less than 1 meter. The GSD is the distance between pixel centers when measured on the ground. Analog (film) satellite imagery is measured in ground resolution.[4]

- Security perimeters (internal and external), 8 entrances (internal and external), and approximately 45 guard positionsGiven the small size of many of the guard positions and the limitations of satellite imagery, these numbers should be viewed as approximate.[5]

- Main prison

- Headquarters, administration, barracks, and support facilities

- Activity in the immediate environment of the facility

- Walled compounds

Based on an analysis of these physical features, political prison camp (kwan-li-so) no. 25, established around 1968, remains an operational prison. Ongoing activity and good maintenance within and in areas immediately surrounding the prison indicate that Kwan-li-so no. 25 is a mature and well-maintained facility by North Korean standards.

Satellite imagery coverage of the facility and previous interviewee testimony continue to indicate that the prison’s economic activity consists of a combination of agricultural production and light industrial manufacturing (i.e., bicycles, wood products, and other products) using forced labor.Interview of former prisoner by HRNK, Seoul, April 23, 2019 (hereafter: Interview i33).[6]

Despite analysis of extensive satellite imagery of the prison during the past 11 years, HRNK is presently unable to confirm or deny escapee and open-source reports that the prison has a prisoner population of approximately 5,000 people. Our analysis of the composition and physical size of the prison suggests that it could accommodate between 2,500 and 5,000 prisoners. However, the population estimate could trend toward the higher end of the range as our composition analysis is anchored to bed count. Overcrowding from a lack of accommodation standards and human concerns can stretch the population estimate toward the high end of facility composition and dimension analysis. At any rate, reports dating from 2021 stating that the prison has a population of 41,000 appear to be exaggerated.Mun Dong Hui, “The Number of Inmates in North Korean Political Prisons Have Increased by at Least 20,000 Since March 2020,” (original article in Korean) Daily NK, July 28, 2021. https://www.dailynk.com/english/number-inmates-north-korean-political-prisons-increased-at-least-20000-since-march-2020/.[7]

As with our analytical caution presented in previous HRNK reports (such as North Korea's Chŭngsan No. 11 Detention Facility),Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., 'North Korea's Chŭngsan No. 11 Detention Facility' (Washington, D.C., Dec. 21, 2020). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Chu%CC%86ngsan%20No_%2011%20Detention%20Facility%20Web.pdf.[8] it is important to reiterate that North Korean officials, especially those associated with the Korean People’s Army, Ministry of Social Security, and various internal security organizations, clearly understand the importance of implementing camouflage, concealment, and deception (CCD) procedures to mask their operations and intentions.

Location and Subordination

Kwan-li-so no. 25 (41.834384°N, 129.725280°E) is located outside the town of Susŏng-dong (수성동, 41.827222°N, 129.736111°E), Ch’ŏngjin-si (청진, Ch’ŏngjin City, 41.887222°N, 129.831944°E), Hamgyŏng-bukto (함경북도, North Hamgyŏng Province)—approximately 7.5 km northwest of Ch’ŏngjin and 458 km northeast of the capital city of P’yŏngyang. Specifically, it is located on the south bank of the Solgol-ch’ŏn (i.e., Solgol stream) across from sections of the village of Susŏng-dong, to which one foot and two road bridges connect it. The prison consists of a moderate-sized walled compound, and headquarters, support, and guard housing areas.

It should be noted that although escapee descriptions of this facility's function and operations match that of other kwan-li-so, the physical characteristics observed in satellite imagery are more representative of the country's kyo-hwa-so (long-term prison labor facilities).For a discussion of the difference between the two types of facilities, see David Hawk with Amanda Mortwedt Oh, The Parallel Gulag: North Korea's 'An-jeon-bu' Prison Camps (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2017), 5-8. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Hawk_The_Parallel_Gulag_Web.pdf.[9] Escapee testimony about Kwan-li-so no. 25 indicates that it "houses political prisoners only, while those who committed economic crimes are not allowed into the facility."Do Kyung-ok et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2015 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, 2015), 122. https://kinu.or.kr/eng/module/report/view.do?idx=113754&nav_code=eng1674806000.[10]

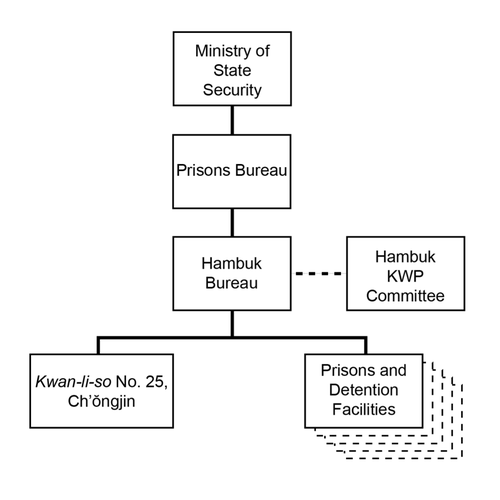

This kwan-li-so is reported to be subordinate to the Ministry of State Security's (MSS) Prisons Bureau.Also known as the “Farm Bureau” and “Farm Guidance Bureau.” See https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/recent-actions/20200513. The United Kingdom identifies “Bureau 7 of the MSS” [likely the Prisons Bureau] as part of its Global Human Rights sanctions regime. UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, Letter to HRNK, dated July 22, 2021.[11] It is likely under the control of the ministry’s North Hamgyŏng Bureau, but it may be subordinate to the ministry’s Ch’ŏngjin-si Bureau.

The MSS reports to the State Affairs Commission, which is chaired by Kim Jong-un, the General Secretary of the ruling Korean Workers' Party (KWP).According to Fyodor Tertitskiy, the MSS is under the de facto control of the Korean Workers’ Party’s (KWP) Organization and Guidance Department (OGD). Tertitskiy also states that the MSS became the Ministry for Protection of the State (국가보위성, Guk-ga-bo-wi-sung) in 2016 under Kim Jong-un. Fyodor Tertitsky, “How the North is Run: The Secret Police,” NK News, July 24, 2018. https://www.nknews.org/pro/how-the-north-is-run-the-secret-police-2/.[12] It was reported in June 2022 that Ri Chang-dae was appointed as the Minister of State Security, replacing Jong Gyong-taek.'North Korea’s sweeping leadership reshuffle could signal policy changes to come,' NKPro, June 16, 2022. https://www.nknews.org/pro/north-koreas-sweeping-leadership-reshuffle-could-signal-policy-changes-to-come/. Jong Gyong-taek is also identified as Jong Kyong Thaek, Jong Kyong-thaek, or 정경택. Jong has since been appointed as the director of the Korean People's Army General Political Bureau. See https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20221208005000325.[13] Jong was sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury in December 2018U.S. Department of the Treasury, 'Treasury Sanctions North Korean Officials and Entities in Response to Regime's Serious Human Rights Abuses and Censorship,' December 10, 2018. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm568.[14] and the European Union in March 2021Official Journal of the European Union 64, no. L 99 I (March 22, 2021): 7, 31. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2021:099I:FULL&from=EN.[15] for his role in perpetrating human rights abuses as the Minister of State Security.

Organization

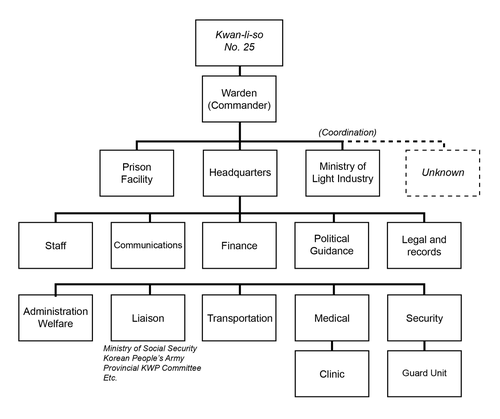

The organizational structure of Kwan-li-so no. 25 is likely similar to that of North Korea's other detention facilities, including its kyo-hwa-so prison labor camps. A provisional organizational structure, based on publicly available information about how North Korea operates its detention facilities, is shown below. There is likely some level of coordination between Kwan-li-so no. 25 and the Ministry of Light Industry, but the camp's relationship with other organizations is unclear.

There is limited information about the forced labor activities imposed on the prisoners at Kwan-li-so no. 25. Interviews with escapees indicate that prisoners at this facility have been engaged in agricultural production, furniture manufacturing, bicycle manufacturing, and other activities. While unconfirmed, prisoners may also be used as forced labor outside the physical confines of the camp. It is also unknown whether there is any economic relationship between Kwan-li-so no. 25 and the light industrial facility (workshop) located immediately outside the northwest corner of the camp.

There are at least 3 military garrisons (likely for both active and paramilitary reserve forces) and 11 air defense artillery sites observed within 5 kilometers of the prison. These air defense sites are well positioned to provide protection to Kwan-li-so no. 25. However, they should be understood as components of the integrated air defense of Ch’ŏngjin-si.No surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites are observed within this area.[16] The closest air facility to Kwan-li-so no. 25 is the Korean People’s Air Force’s Sŭngam-ni Airbase, located approximately 18 kilometers to the south-southwest and a small partially complete air club/UAV airfield approximately 1 kilometer northwest. Sŭngam-ni is a training base. Due to its mission, organization, and location, it almost certainly provides no support to Kwan-li-so no. 25. Likewise, the incomplete air club/UAV airstrip provides no support to Kwan-li-so no. 25.

While the prison is likely connected to the regional telephone network, it is likely via buried service, as no evidence of overhead service was identified in satellite imagery. The prison is connected to the regional electric power grid via overhead high voltage power transmission cables that run from the prison to a substation approximately 1 kilometer to the southeast. The nearest rail facility is the rail station at Susŏng-dong, 800 meters to the east of the prison.

Minor Construction Activity

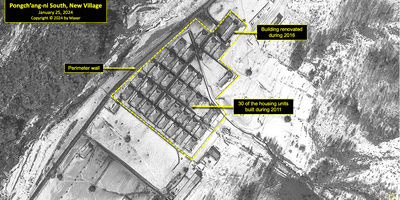

Readers are encouraged to review the development of Kwan-li-so no. 25 between 2003 and 2021, as analyzed in our previous four reports on this facility.Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr. et al., 'North Korea’s Political Prison Camp, Kwan-li-so No. 25, Update 3' (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Sep. 30, 2021). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Bermudez_KLS25_FINAL.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., 'North Korea’s Camp No. 25 Update-2' (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Nov. 29, 2016). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/ASA_HRNK_Camp25_Update2.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., 'North Korea’s Camp No. 25 Update' (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Jun. 5, 2014). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Camp%2025%20Update%20Good.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. and Micah Farfour, 'North Korea’s Camp No. 25' (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Feb. 25, 2013). http://hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_Camp25_201302_Updated_LQ.pdf.[17] This report only addresses major changes between 2021 and 2023.

Our analysis shows that the prison and associated agricultural and light industries were active from 2021 to 2023. This is indicated by ongoing maintenance of agricultural fields and orchards, the planting and harvesting of different crops over the years, movement of vehicles and supplies at the camp's light industry facilities, and people observed throughout the facility. Most changes observed to the physical infrastructure of Kwan-li-so no. 25 were minor in nature and typical of what had previously been observed at the prison. These changes include rearrangement, razing or construction of small structures, and minor adjustments of roads and trails.

Located in the southeastern corner of Kwan-li-so no. 25 is a small 690 m2 (823 yd2) compound with a high security wall. Inside the compound is a 160 m2 (190 yd2) single-story building. Approximately 100 meters to the east is a 115 m2 (138 yd2) single-story building. Both structures were constructed during 2010 and remain today.

This walled compound is relatively isolated within the prison, and it is overlooked by 12 guard positions. Moreover, its size and construction are not consistent with North Korean practices for the storage of heavy equipment or munitions. Therefore, the most reasonable explanation for the walled compound is that it is a high-security prison compound for prisoners of significant importance. The adjacent single-story building is likely for guard or support personnel, as it is not enclosed by a high-security wall. These buildings have not changed noticeably since their construction and remain active.

Sometime between February and August 2018, a second walled compound was constructed 50 meters to the east of the high-security compound. This approximately 198 m2 (237 yd2) compound is surrounded by a security wall and contains an approximately 48 m2 (57 yd2) building. The presence of an opening in the security wall suggests that it is not a high-security compound. Although the purpose of this compound is unknown, its proximity to the existing high-security compound indicates a close association.

Overall Assessment

Taken in context with previous high-resolution satellite imagery analysis, analysis of recent high-resolution satellite imagery of Kwan-li-so no. 25 and its environment indicates the following.

- Kwan-li-so no. 25 remains an operational prison facility that has witnessed minor changes between 2021 and 2023. These changes appear to be typical of those observed at other North Korean detention facilities. It remains a mature and well-maintained prison facility by North Korean standards.

- The current prisoner population is employed to both maintain the agricultural fields, orchards, and livestock and to work in the prison's wood products and light industrial factories.

- Perimeter walls, fences, and gates are well maintained and in good repair.

- Guard positions are well positioned to provide overlapping fields-of-view of the prison and are well maintained and in good repair.

- Administrative buildings, barracks, housing, cultural buildings, support buildings, and grounds are well maintained and in good repair.

- The grounds and buildings (i.e., wood products factory, light industrial facility, and prisoner housing) of the central compound appear to be moderately well maintained and in a moderate state of repair.

- The wood products and light industrial factories appear to be operating, as suggested by the presence of various numbers of vehicles, supplies, and the changing size and shape of the associated wood chip/sawdust piles.

- All agricultural fields are well-defined, maintained, and irrigated. The fields to the north of the prison have crops under cultivation through almost all four seasons of the year.

- The livestock structures are well maintained and in use.

- There is likely both an important economic and social relationship between Kwan-li-so no. 25 and the adjacent villages of Susŏng-dong and Songgong-ni.

- It is unknown if there is any economic relationship between Kwan-li-so no. 25 and the light industrial facility (workshop) immediately outside the northwest corner of the prison.

Background for Context

The United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in North Korea (UN COI) determined that “crimes against humanity have been committed in North Korea, pursuant to policies established at the highest level of the State.”UN Human Rights Council, Report of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, UN Doc. A/HRC/25/63, February 7, 2014, p. 14. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/co-idprk/reportofthe-commissionof-inquiry-dprk.[18] Many of these crimes against humanity take place against persons detained in political and other prisons—persons who the Commission determined are among the “primary targets of a systematic and widespread attack” by the North Korean regime,Ibid.[19] including murder, enslavement, torture, imprisonment, rape, forced abortions and other sexual violence, persecution on political grounds, and the enforced disappearance of persons. According to the UN COI, “The unspeakable atrocities that are being committed against inmates of the kwan-li-so political prison camps resemble the horrors of camps that totalitarian States established during the twentieth century.”Ibid., p. 12.[20]

Based on research conducted by HRNK, seven trends have defined the human rights situation under the Kim Jong-un regime:

- an intensive crackdown on attempted defections;

- a restructuring of the political prison camp system, with some facilities closer to the border with China being shut down, while inland facilities have been expanded, and construction of internal high-security compounds within the prisons;

- the sustained, if not increased, economic importance of the political prison camps;

- the disproportionate oppression of women by North Korean officials. Women have assumed primary responsibility for the survival of their families and thus represent the majority of those arrested for perceived wrongdoing at the jangmadang markets, or for "illegally" crossing the border;

- an aggressive purge of senior officials, aimed at consolidating the leader's grip on power;

- targeting of North Korean escapees; and

- increased focus on eliminating "anti-reactionary" thoughts.

While commercially available satellite imagery allows the outside world to see guard positions and often people, for example in political prison camps, the full extent of Kim Jong-un’s human rights violations in the camps remains hidden. Nevertheless, the continued monitoring of such camps provides a way to shed some light on the abuses endured by North Korea’s most vulnerable—its political prisoners, who are oppressed through unlawful arrest, detention, torture, inhospitable prison conditions, sexual violence, and public and private executions.

References

- Previous reports in the project can be found at https://www.hrnk.org/publications/hrnk-publications.php.

- Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., "North Korea Camp No. 25 – Update 2" (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Nov. 29, 2016). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/ASA_HRNK_Camp25_Update2.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., "North Korea Camp No. 25 – Update" (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Jun. 5, 2014). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Camp%2025%20Update%20Good.pdf; and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., “Satellite Imagery Shows Captives Inside Camp No. 25 in North Korea,” HRNK Insider, Aug. 8, 2018. https://www.hrnkinsider.org/2018/08/satellite-imagery-shows-captives-inside_30.html.

- Some interviewees and researchers have occasionally identified the facility as “Political Prison Camp 25,” “Camp 25,” or the “Susŏng-dong" kyo-hwa-so (long-term prison labor facility).

- The term “high resolution” in this report refers to digital satellite images with a ground sample distance (GSD) of less than 1 meter. The GSD is the distance between pixel centers when measured on the ground. Analog (film) satellite imagery is measured in ground resolution.

- Given the small size of many of the guard positions and the limitations of satellite imagery, these numbers should be viewed as approximate.

- Interview of former prisoner by HRNK, Seoul, April 23, 2019 (hereafter: Interview i33).

- Mun Dong Hui, “The Number of Inmates in North Korean Political Prisons Have Increased by at Least 20,000 Since March 2020,” (original article in Korean) Daily NK, July 28, 2021. https://www.dailynk.com/english/number-inmates-north-korean-political-prisons-increased-at-least-20000-since-march-2020/.

- Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., "North Korea's Chŭngsan No. 11 Detention Facility" (Washington, D.C., Dec. 21, 2020). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Chu%CC%86ngsan%20No_%2011%20Detention%20Facility%20Web.pdf.

- For a discussion of the difference between the two types of facilities, see David Hawk with Amanda Mortwedt Oh, The Parallel Gulag: North Korea's "An-jeon-bu" Prison Camps (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2017), 5-8. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Hawk_The_Parallel_Gulag_Web.pdf.

- Do Kyung-ok et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2015 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, 2015), 122. https://kinu.or.kr/eng/module/report/view.do?idx=113754&nav_code=eng1674806000.

- Also known as the “Farm Bureau” and “Farm Guidance Bureau.” See https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/recent-actions/20200513. The United Kingdom identifies “Bureau 7 of the MSS” [likely the Prisons Bureau] as part of its Global Human Rights sanctions regime. UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, Letter to HRNK, dated July 22, 2021.

- According to Fyodor Tertitskiy, the MSS is under the de facto control of the Korean Workers’ Party’s (KWP) Organization and Guidance Department (OGD). Tertitskiy also states that the MSS became the Ministry for Protection of the State (국가보위성, Guk-ga-bo-wi-sung) in 2016 under Kim Jong-un. Fyodor Tertitsky, “How the North is Run: The Secret Police,” NK News, July 24, 2018. https://www.nknews.org/pro/how-the-north-is-run-the-secret-police-2/.

- "North Korea’s sweeping leadership reshuffle could signal policy changes to come," NKPro, June 16, 2022. https://www.nknews.org/pro/north-koreas-sweeping-leadership-reshuffle-could-signal-policy-changes-to-come/. Jong Gyong-taek is also identified as Jong Kyong Thaek, Jong Kyong-thaek, or 정경택. Jong has since been appointed as the director of the Korean People's Army General Political Bureau. See https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20221208005000325.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, "Treasury Sanctions North Korean Officials and Entities in Response to Regime's Serious Human Rights Abuses and Censorship," December 10, 2018. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm568.

- Official Journal of the European Union 64, no. L 99 I (March 22, 2021): 7, 31. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2021:099I:FULL&from=EN.

- No surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites are observed within this area.

- Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr. et al., "North Korea’s Political Prison Camp, Kwan-li-so No. 25, Update 3" (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Sep. 30, 2021). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Bermudez_KLS25_FINAL.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. et al., "North Korea’s Camp No. 25 Update-2" (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Nov. 29, 2016). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/ASA_HRNK_Camp25_Update2.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., "North Korea’s Camp No. 25 Update" (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Jun. 5, 2014). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Camp%2025%20Update%20Good.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. and Micah Farfour, "North Korea’s Camp No. 25" (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Feb. 25, 2013). http://hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_Camp25_201302_Updated_LQ.pdf.

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, UN Doc. A/HRC/25/63, February 7, 2014, p. 14. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/co-idprk/reportofthe-commissionof-inquiry-dprk.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 12.

Look Ahead

HRNK will continue to use satellite imagery to assess the operational status of North Korea's political prison camps (kwan-li-so), including kwan-li-so no. 14, 15, 16, and 18. This analysis will be augmented with escapee testimony and open-source information whenever possible, and it will also seek to identify major changes at these facilities. North Korea's intensified crackdown on attempted escapes and the consumption & distribution of foreign information may have been accompanied by the reorganization or expansion of key detention facilities. In addition, HRNK will seek to develop a more complete picture of North Korea's network of detention facilities by looking beyond the kwan-li-so and the kyo-hwa-so to examine other types of facilities through satellite imagery.

Things to Watch

- How have North Korea's detention facilities changed amidst the Kim Jong-un regime's efforts to exert greater control over the population during and after the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Next report will provide updates on Camp 18

About The Authors

Senior Fellow for Imagery Analysis, HRNK

Executive Director, HRNK

Director of Operations & Research, HRNK

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.