Overview

Myanmar has been embroiled in violence since the military staged a coup d'état overthrowing the government in 2021. The country's air force has waged deliberate campaigns targeting rebel groups and civilians alike throughout the country, striking hospitals, schools, and religious buildings. In the years preceding civil war, the Myanmar Air Force (MAF) improved its aerial strike capabilities by upgrading infrastructure and procuring additional offensive aircraft, according to regional media.[1]

Over the course of the civil war, and in violation of the Geneva Convention's Additional Protocols of 1977 prohibiting the attack of noncombatant populations, the MAF has used a wide variety of Russian and Chinese-made aircraft to intentionally strike civilians, according to human rights organization reporting. [2] This analysis of air base infrastructure and aircraft upgrades can provide evidence for accountability in potential post-conflict human rights cases.

Activity

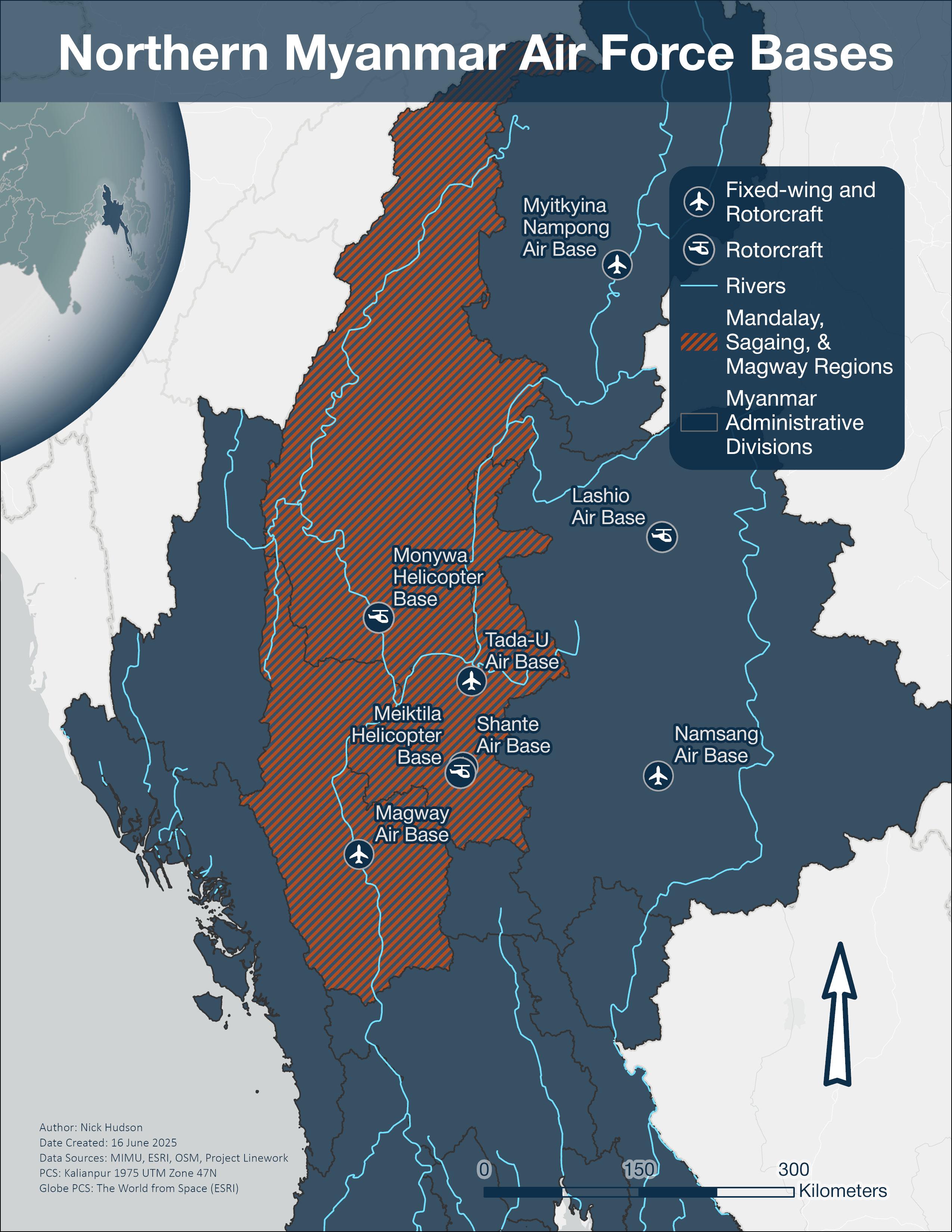

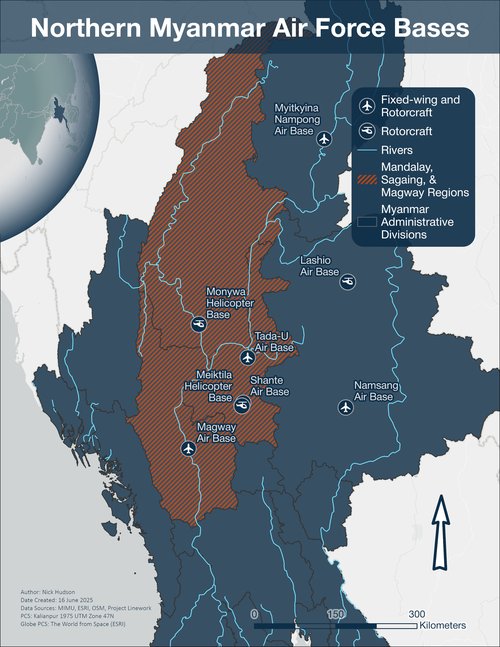

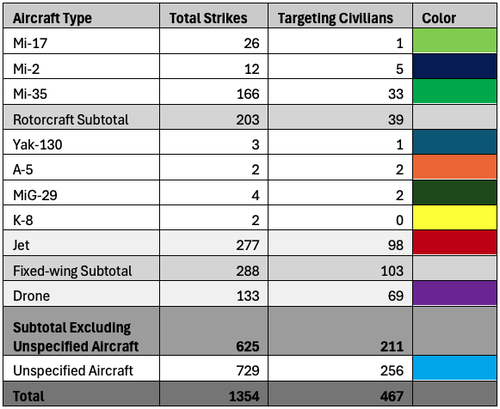

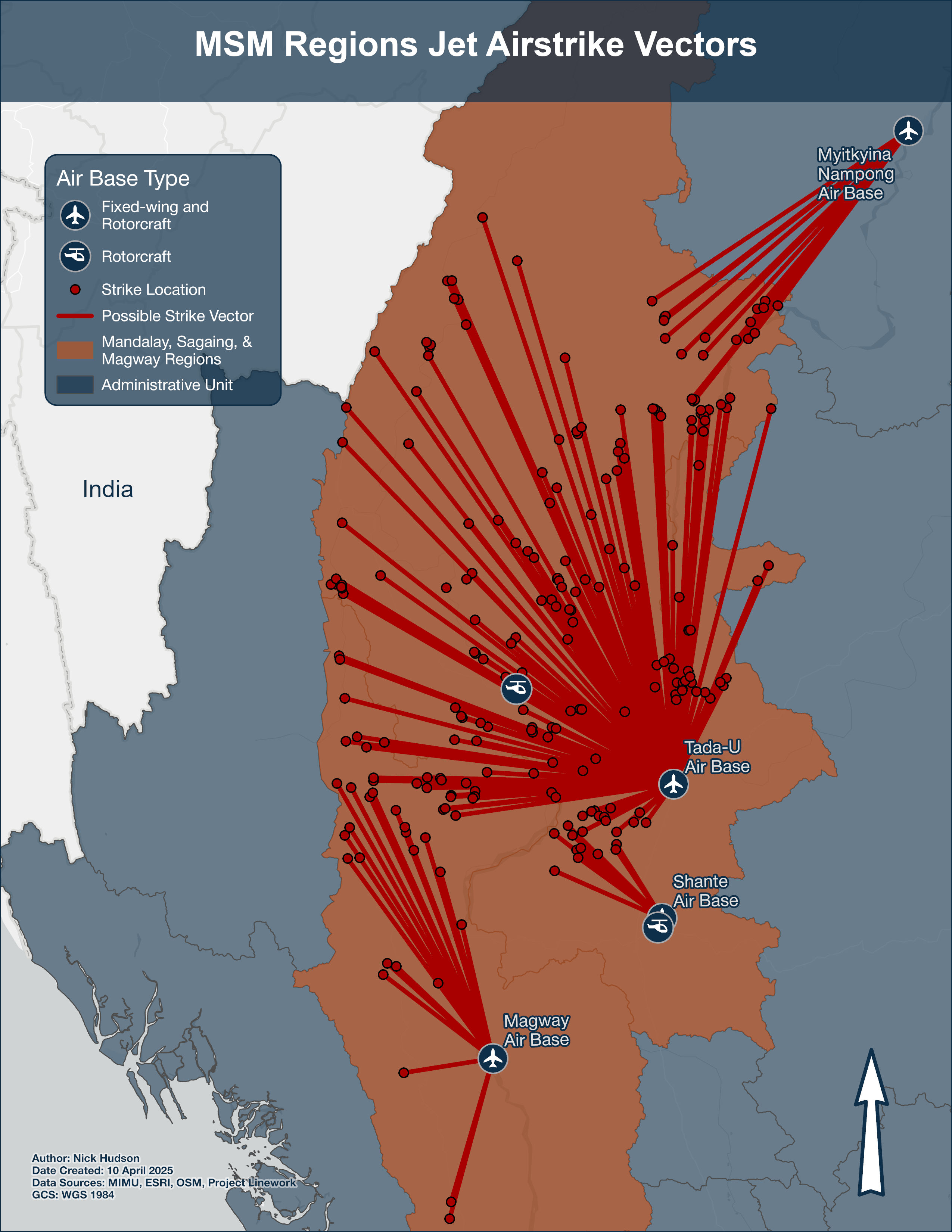

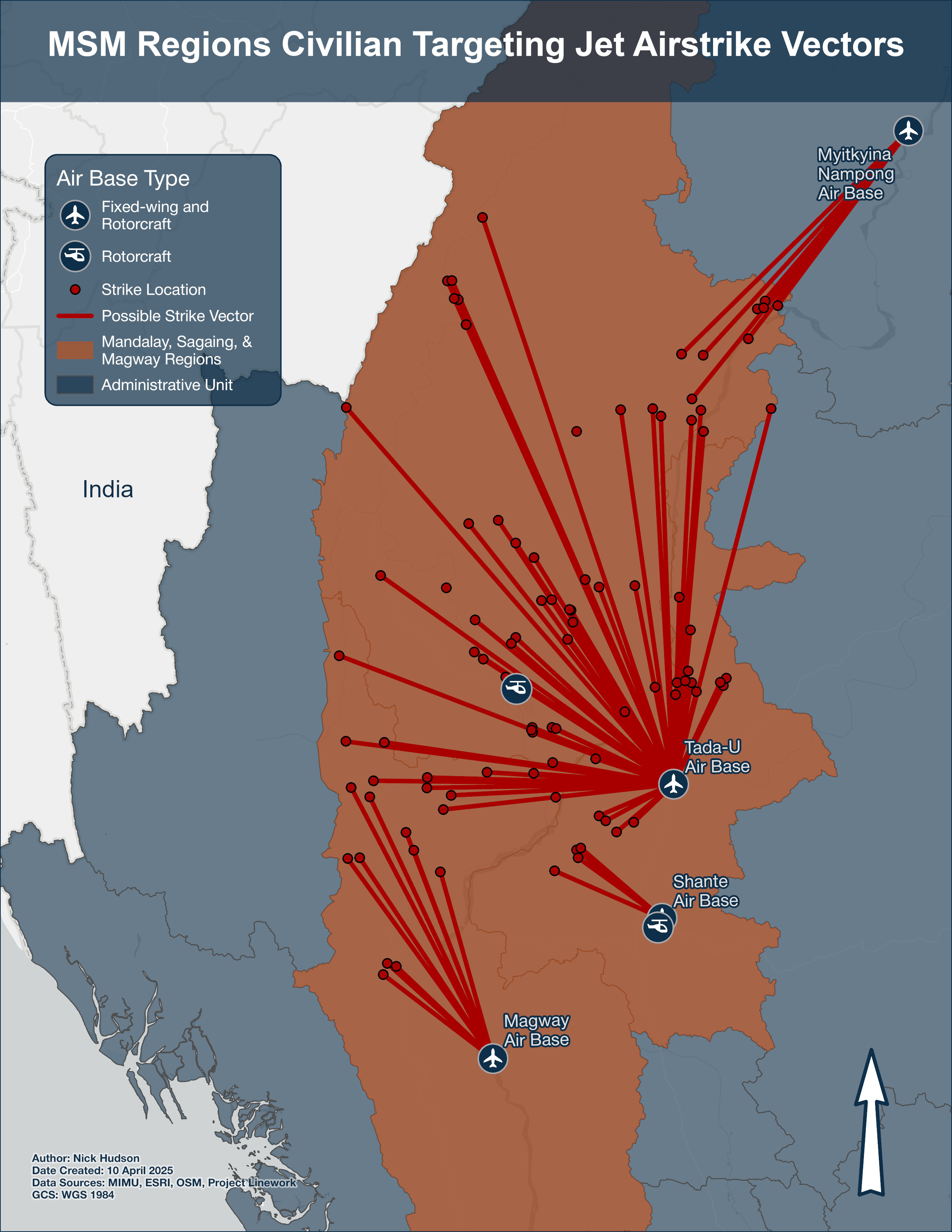

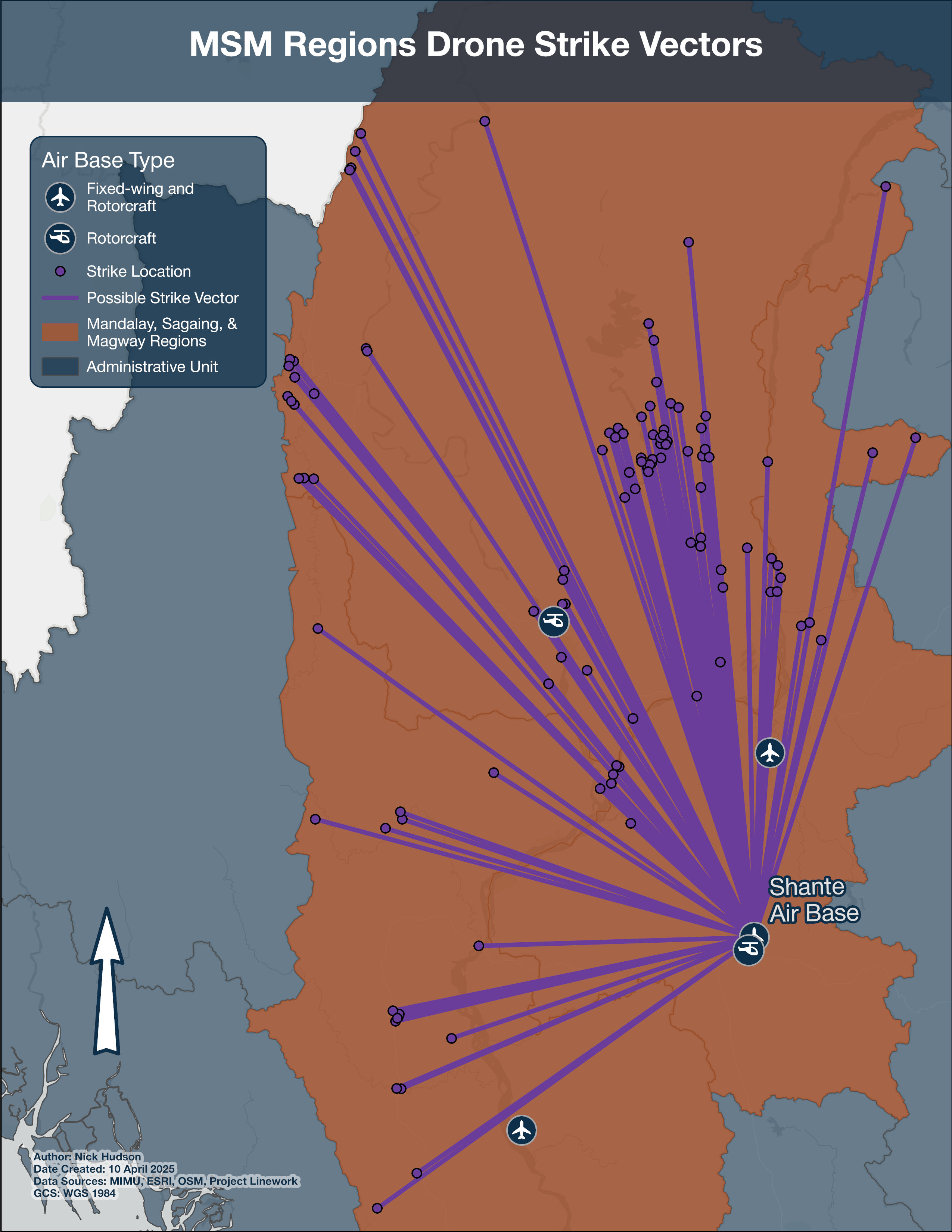

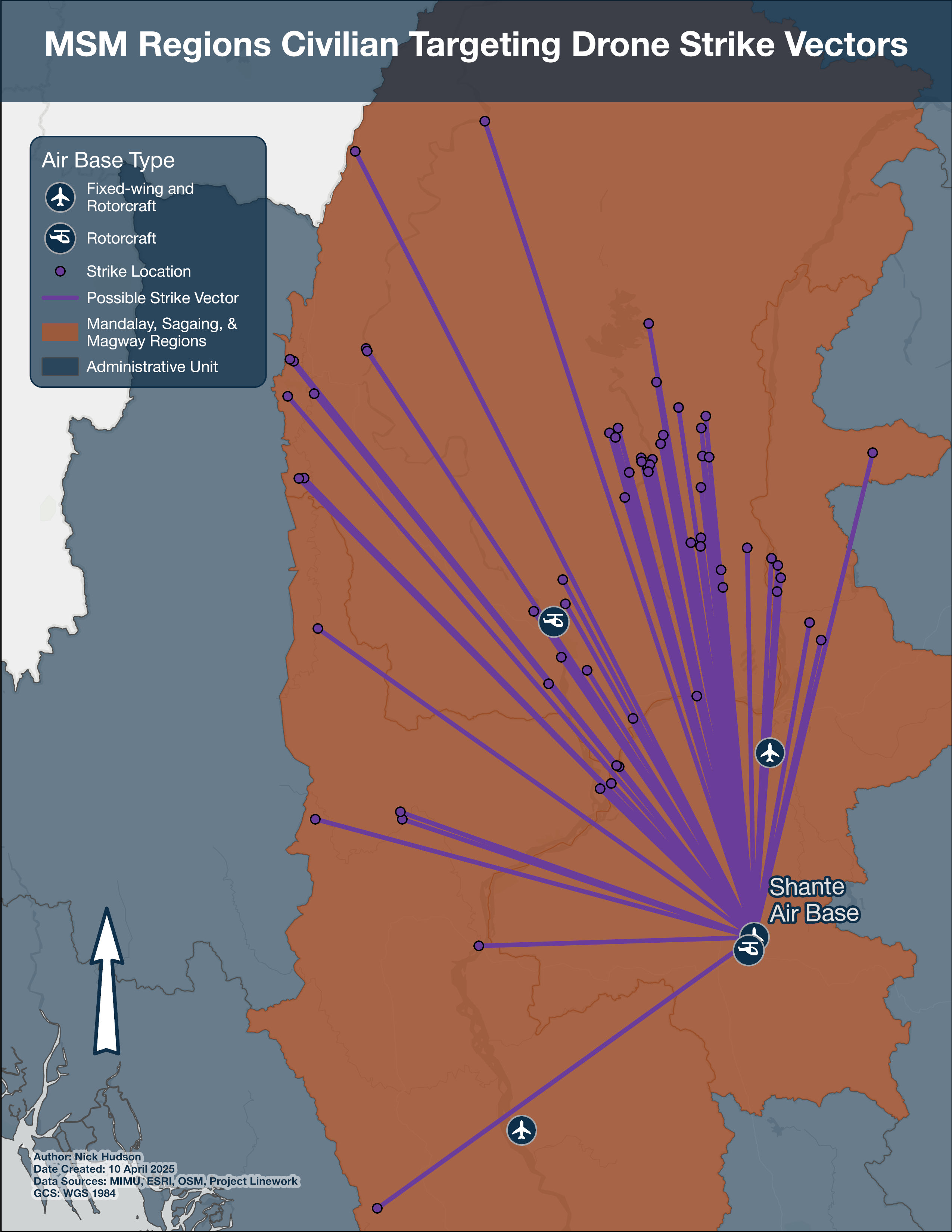

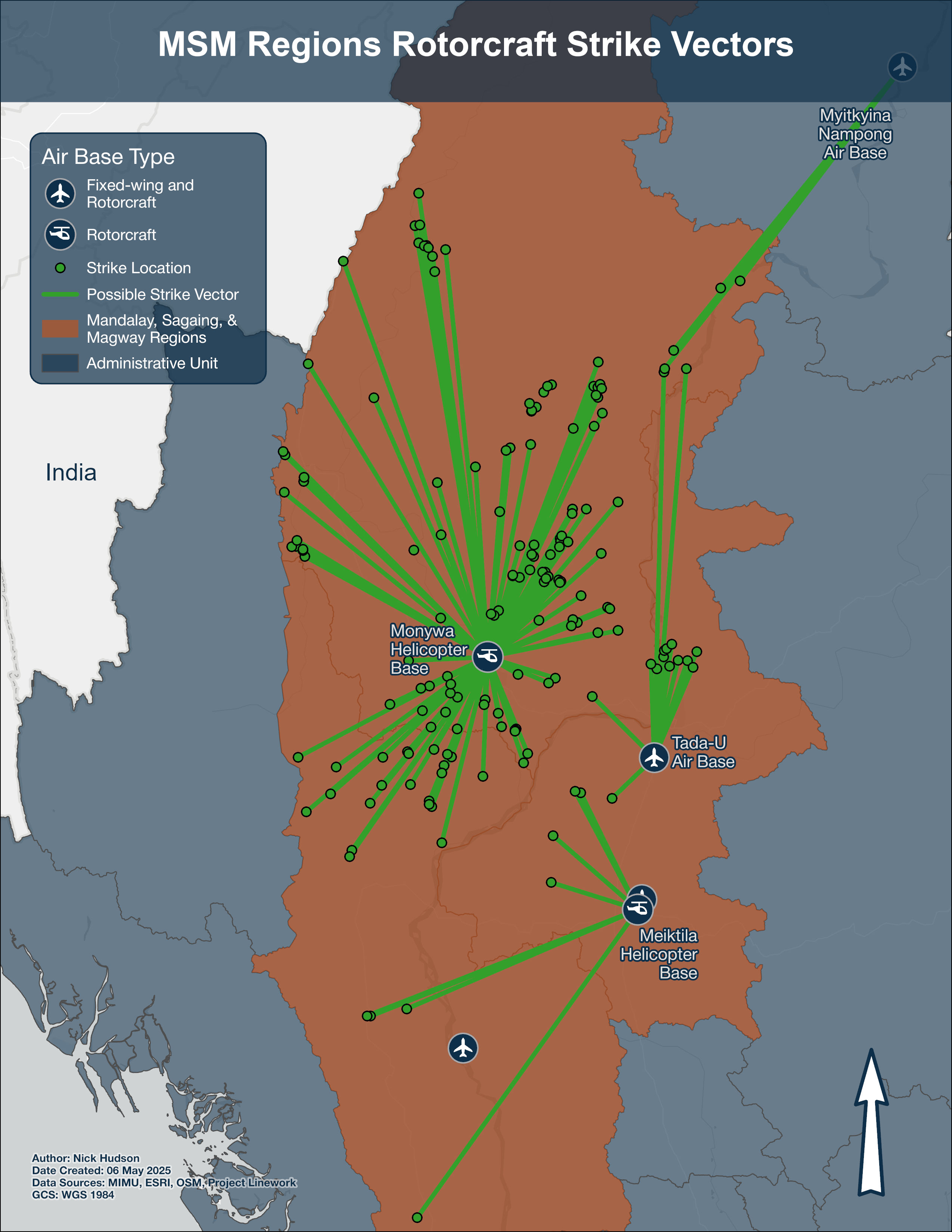

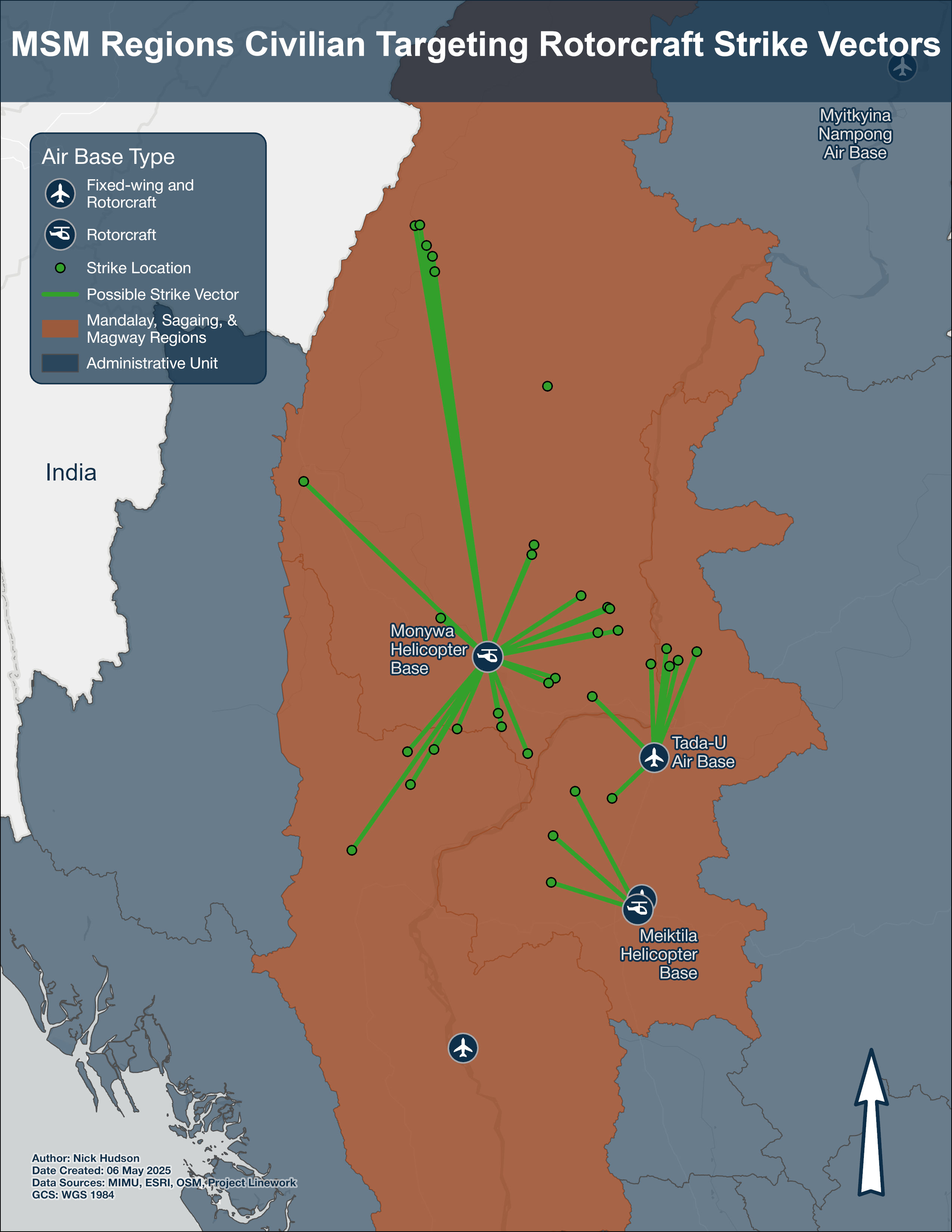

This geospatial report investigates the aircraft delivered, airbase facilities upgraded, and civilian infrastructure attacked by the MAF between February 2021 and March 2025, the first four years of the Myanmar civil war. Using strike-vector analysis from airbases to village strike locations in the Mandalay, Sagaing, and Magway (MSM) regions, the report finds MAF airstrikes targeting civilians occurred from all the airbases studied in north-central Myanmar during this timeframe. While there exists no significant difference between the mean distance travelled by aircraft when targeting civilians versus rebels, each aircraft type possesses a different average attack radius. In order from largest to smallest in range, drones flew 212km, jet aircraft 148km (including Yak-130, A-5, MiG-29 and K-8), and the Mi-35P helicopter 94km on average from airbase to target in the MSM regions. The most frequently identified type of aircraft targeting civilians was the Mi-35P attack and transport helicopter with 33 airstrikes; the broad categories of jet and drone were responsible for 98 and 69 civilian targeting airstrikes. MAF aerial attacks predominantly occurred during the driest months of the year, between November and February/March, when there is the least cloud cover. According to the strike vector analysis, the primary airbase for jet airstrikes is Tada-U Airbase, Shante for drone operations, and Monywa for helicopters and staging before strikes in Sagaing. [Editorial Note: This article follows the author's selected terminology in using “Myanmar” in place of “Burma.”]

Background

On the morning of February 1, 2021, one day before Myanmar’s Parliament was set to endorse an overwhelming majority national vote for Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League of Democracy, the military junta, led by Min Aung Hlaing, arrested the winning candidates and claimed control in a coup.Sebastian Strangio, “Protests, Anger Spreading Rapidly in the Wake of Myanmar Coup,” The Diplomat, February 8, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/02/protests-anger-spreading-rapidly-in-the-wake-of-myanmar-coup/[3] Initial resistance began as peaceful protests that met harsh, deadly retaliation by government forces, leading the country on a path to civil war. The repression and violence compelled diaspora members to form a National Unity Government in exile while those who remained in Myanmar rallied together to form the Peoples Defense Force (PDF) in the north-central part of the country.Richard C. Paddock, “Myanmar coup: What to know about the protests and unrest,” The New York Times, December 9, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/article/myanmar-news-protests-coup.html[4]

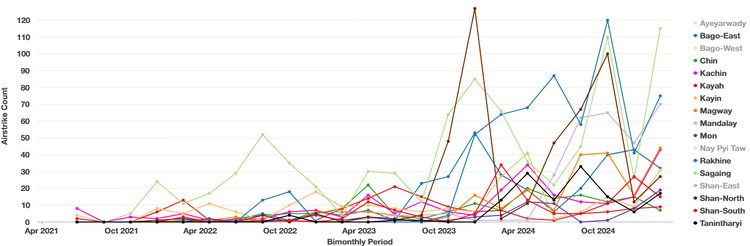

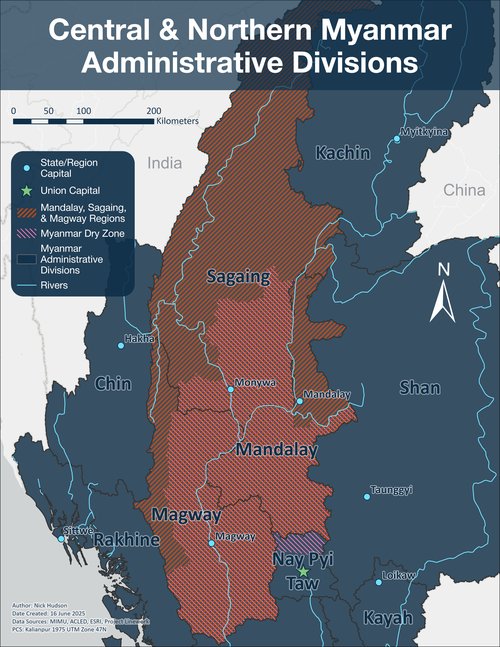

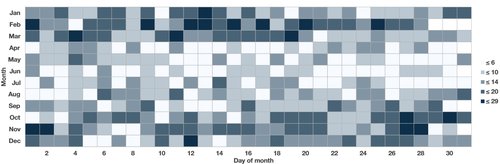

As of February 2025, the militaryState Administration Council (SAC), Junta, Tatmadaw, and military all refer to Myanmar state forces[5] crackdown on the rebelling civilian population has resulted in an estimated 13,500 ‘civilian targeting’ deaths, over 20,000 arbitrary detentions, and more than 3.5 million internally displaced people (IDP).ACLED, “Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED),” Data set, Myanmar, March 21, 2025, http://www.acleddata.com/. The data downloaded from ACLED exclusively looked at events in Myanmar between February 1st, 2021, and March 21st, 2025. The only alteration of the original dataset was to add a field for date queries in ArcGIS Pro. No data were added or amended from the dataset. This applies for all other analysis sections.[6]Amnesty International, “Myanmar: Four Years After Coup, World Must Demand Accountability for Atrocity Crimes,” January 31, 2025, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/01/myanmar-four-years-after-coup-world-must-demand-accountability-for-atrocity-crimes/[7]“Myanmar UNHCR Displacement Overview 31 Mar 2025,” UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP), April 3, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/115466.[8] The Tatmadaw (local name for Myanmar’s armed forces) has tried various different methods to ‘fight fire with fire’ by torching villages in north central Myanmar and a significantly ramped-up airstrike campaign against rebels and civilians over the past year and a half to “pacify through fear.”Morgan Michaels, “Fighting rages along Myanmar’s transport routes,” IISS Myanmar Conflict Map (International Institute for Strategic Studies, September 2023), accessed April 12, 2025, https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2023-09.[9]Centre for Information Resilience, “Impact of ‘pacify Through Fear’ Strategy From Myanmar Military - Centre for Information Resilience,” October 14, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/articles/open-source-analysis-reveals-impact-of-new-myanmar-military-operation-designed-to-pacify-through-fear/[10] See Figure 1 for a visualized representation of increased air and drone strike activity since October 2023. One third of all MAF air and drone strikes hit Mandalay, Sagaing, or Magway, three administrative divisions which encompass Anyar.

Anyar, also referred to as the Dry Zone, is the main homeland for the Burmese ethnic majority Bamar people , and has a semi-arid climate in the rain shadow of the Arakan Mountains which catch the brunt of monsoons before they reach the valley. Two rivers, the Chindwin and Irrawaddy, act as main arteries for the transportation of goods in an area where road travel is unreliable. The Dry Zone is considered the area with the most intense ground fighting since February 2021 and accordingly 385 airstrikes were categorized as ‘civilian targeting’ in the Myanmar, Sagaing, and Magway (MSM) regions.Centre for Information Resilience, “An Epicentre of Violence: A Sagaing Region Anthology - Centre for Information Resilience,” Centre for Information Resilience, December 31, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/reports/an-epicentre-of-violence-a-sagaing-region-anthology/[11] Before the 2021 coup, the MSM region was comprised of Bamar Buddhists, Christian Chins, and other historically disregarded minorities. The younger generation took up arms against the government, joining the PDF and local militias, gaining significant territory in the Dry Zone, where the regime’s foothold was weakest.Centre for Information Resilience, “Why Is Sagaing the Epicentre of Myanmar’s Conflict?,” February 20, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/articles/why-is-sagaing-the-epicentre-of-myanmars-conflict/[12] Since the coup, 33.36% of MAF air and drone strikes have targeted civilians in the MSM regions.“Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Codebook (ACLED)” (October 7, 2024), accessed June 14, 2025, https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2024/10/ACLED-Codebook-2024-7-Oct.-2024.pdf[13] No drone strikes by rebel groups have targeted civilian populations.

The MAF aerial capabilities were made possible by a modernization campaign that started in 2014-2015, when the MAF’s budget and procurement of aircraft significantly ballooned. Massive overhauls to airbase infrastructure, taxiways, aircraft aprons and the construction of new hangers and aircraft coverings had all been completed to accommodate the arrival of new, modern aircraft. The modernized air force has not been used for the defense of Myanmar’s territorial integrity but instead in an offensive role against the domestic population and rebel groups. In a UN report from Spring 2023, the Myanmar military imported at least $1 billion USD in arms, equipment, and raw materials to manufacture weapons, mostly from Russia, China and Singapore, between the 2021 coup and May 2023.Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, The Billion Dollar Death Trade: The International Arms Networks that Enable Human Rights Violations in Myanmar, Online, 53rd session (UN Human Rights Council, 2023), 4, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/myanmar/crp-sr-myanmar-2023-05-17.pdf[14]The $1 billion USD in imports supporting the defense industry were in amounts listed from the following countries: $406 million USD from entities in the Russian Federation, including state-owned entities; $267 million USD from entities in China, including state-owned entities; $254 million USD from entities operating in Singapore; $51 million USD from entities in India, including state-owned entities; $28 million USD from entities operating in Thailand.[15]

The use of this newly acquired weaponry by the military junta impacted both rebel groups and the civilian population. More than 17 different armed organizations are currently fighting against the Tatmadaw, another name for the military junta. The main factions involved in fighting the military junta are as follows: The PDF, with an estimated 100,000 fighters, maintains lofty aims of overcoming the well-equipped Tatmadaw using guerrilla warfare tactics to reinstate democratic governance at the national level.Banyar Aung, “An assessment of Myanmar’s parallel civilian govt after almost 2 years of revolution,” The Irrawaddy, August 4, 2023, https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/analysis/an-assessment-of-myanmars-parallel-civilian-govt-after-almost-2-years-of-revolution.html[16] Competing regional ethno-nationalist rebel groups and alliances are simultaneously fighting to stake claims to different portions of territory currently controlled by the junta.

Another important player in the conflict is The Brotherhood Alliance. This faction was formed in June 2019, between the Arakan Army (in control of Rohingya area of Myanmar in Rakhine State), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army. While the Brotherhood Alliance is currently allied with the PDF against the Junta, it has much more prominent nationalistic goals in the conflict. The Alliance only started to fight against the Junta in 2023 with a massive offensive called Operation 1027 in northern Shan State, conquering the city of Lashio in northern Shan State in August 2024.Morgan Michaels, “Is the Brotherhood headed to Mandalay?,” IISS Myanmar Conflict Map (International Institute for Strategic Studies, October 2024), accessed April 12, 2025, https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2024-09[17]

This geospatial report analyzes the ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data) dataset documenting air base infrastructure, aircraft involved in MAF airstrikes, a subset of ACLED strikes that hit civilian infrastructure, and vector analysis from airbases to strike points in the MSM regions in north-central Myanmar.

Data and Methodology

Leveraging the ACLED dataset, which is trusted by a wide range of organizations reporting on Myanmar including the International Institute for Strategic Studies and the Centre for Information Resistance, all events between February 1, 2021 and March 21, 2025 were converted into point data using ArcGIS Pro.ACLED[18] The ACLED dataset was used as the basis for the base air and drone strike calendar year and region analysis and in-part to determine common types of aircraft striking civilians and civil infrastructure in the MSM regions as mentioned in local news articles. Each airstrike event is accompanied with an identifying event code, latitude and longitude, interaction type, geoprecision score, source name, fatality total, civilian targeting designation, and a summary of the event in the notes section. The determination whether an event is considered ‘civilian targeting’ is when “civilians were the main or only target of an event” and “events in which civilians were incidentally harmed are not included in this category.”Ibid.[19] Data points with a geoprecision score higher than 2 were eliminated to ensure spatial analysis results would be meaningful (no more than 10 datapoints). An initial search for rebel vs civilian event interactions yielded no results but under half of the documented air or drone strikes in Myanmar are launched by rebels against Tatmadaw forces. The dataset was again subdivided to include only air or drone strikes occurring in Myanmar’s MSM regions to focus on the area with the highest concentration of activity.

For temporal analysis, a Jenks natural breaks method was used to divide the frequency of air and drone strikes over a calendar year into five classes. The Jenks natural breaks method of data clustering minimizes the variation between ranges of values while leaving no gaps between classes.Rhumbline Studio, “Classification Methods: Equal Interval, Natural Breaks (Jenks), Geometric Interval, Quantile,” October 12, 2015, accessed June 15, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ebL8OvG8Jc[20]

Discovering what aircraft to look for at airbases was based on the ACLED database, Janes, Embraer’s World Air Force Directory, and Myanmar Witness’ geospatial reporting to identify those that carried out airstrikes in the MSM regions. Homalin Air Base, located in the northern part of Sagaing region, is assessed as having an operational 3780m runway, but is designated for civilian use and therefore will not be examined.

When documenting phenomena in the ACLED database, four decimal places are used in the latitude and longitude fields to identify approximate geolocation, meaning it would theoretically be possible to identify where airstrikes took place on a street within 12 meters of the actual location. However, the approximation used is at the level of the city, town, or village center instead of a specific building. Hypothetically it would be possible to use the ACLED coordinates to confirm airstrikes had indeed hit a particular building type, yet this requires both before and after imagery of airstrike locations, which is relatively difficult to find given that 58.2% of all airstrikes occurred between March 2024 and March 2025 and image catalogues are inconsistent. Therefore, a random subset of 50 from 187 airstrikes that hit schools, hospitals, clinics, or religious buildings occurring between May 31, 2021 and March 18, 2025 were selected from the MSM regions for verification. Nine of the fifty strikes in the sample have a geoprecision rating of 2, meaning the phenomena occurred generally within a designated township, since 18.64% of the strikes in this region had this level of observation precision. The geocoordinates for these events were then verified using panchromatic and multispectral imagery from either the Maxar GEGD imagery portal or Google Earth. An Excel spreadsheet including the ACLED Event ID, coordinates for the village center & more precise building coordinates, the most recent imagery, and sources for before and after each strike, observations, and original event notes is provided. excelACLED ResourceACLED Resource

The requirements for choosing imagery are as follows: 1) the imagery must not cut off any part of the village being viewed and the target area should be largely cloud-free 2) imagery resolution size must be 50cm or better in either panchromatic or multispectral imagery 3) the “prior” image must be taken within a year before the airstrike date and 4) the “post” image must be taken within six months following the airstrike date. An assumption being made is that generally when the bombs fall in Myanmar, civilians are typically unable to make quick repairs to structures after an airstrike. The expectation is that post-airstrike imagery analysis should yield relatively good results in exposing war crimes against civilian infrastructure such as schools, hospitals/clinics, and religious buildings, yet this hypothesis proved difficult to confirm using only satellite imagery. 46% of the locations had no post-airstrike imagery in the selected libraries while four of nine 2nd level geoprecision-coded aerial strikes were unable to be found at all. Additionally, the transliteration of Burmese into Latin script is highly inconsistent.

Air and Drone Strike Analysis

The Tatmadaw’s campaign against civilians has become increasingly violent, with the number of airstrikes delivered between 2024 and 2025 doubling from the previous year. From March 21, 2024 to March 20, 2025 the MAF launched 2,267 aerial strikes or 58.2% of all airstrikes in Myanmar and documented in ACLED, compared to 1,127 airstrikes from March 2023 to March 2024 (A 101% increase year-over-year).ACLED[21]Clionadh Raleigh, Roudabeh Kishi, and Andrew Linke, “Political Instability Patterns Are Obscured by Conflict Dataset Scope Conditions, Sources, and Coding Choices,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10, no. 1 (February 25, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01559-4[22] Accordingly, the average number of daily airstrikes increased from 5.1 to 10.82. Despite the marked increase in intensity, the distribution of aerial attacks is highly uneven throughout the course of a year. Employing a calendar heat chart revealed a seasonal pattern to air and drone strike activity during the Myanmar Civil War through mid-March 2025. 52.2% of aerial strikes by the MAF occurred during the country’s dry winter season, which runs from November to February.Richard Powell, “The Climate of Myanmar,” Blue Green Atlas, accessed April 12, 2025, https://bluegreenatlas.com/climate/myanmar_climate.html[23] March marks the beginning of the two-month hot season, when there typically was a drawdown in the frequency of airstrikes.Ibid.[24] For the majority of April through August there were relatively few airstrikes. For the first three years of the conflict, the MAF has maintained this seasonal pattern.

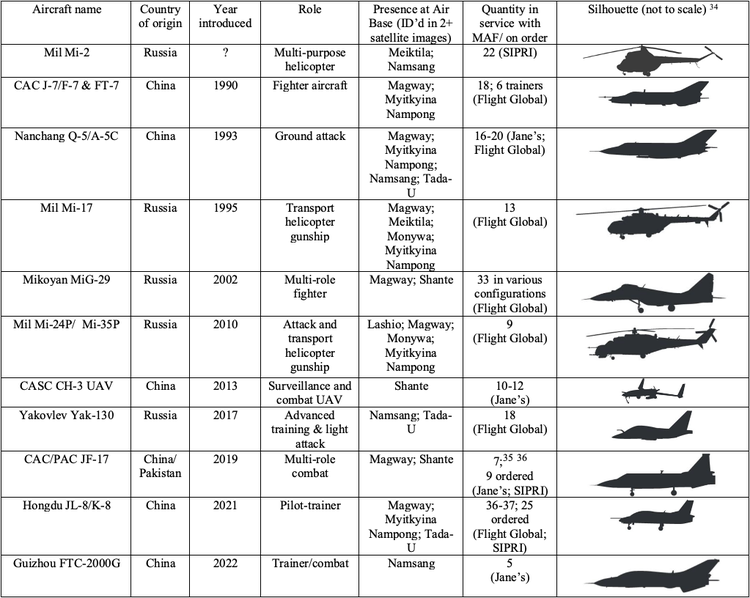

Analysis of ACLED event descriptions from March 2021 to March 2025 found 1154 airstrikes were executed in the MSM regions, with the broadest categories of jet, drone, and “aircraft” responsible for 242, 116, and 592 strikes, respectively. The three most frequently identified rotorcraft attacking ground targets were all Russian-made, with 159 airstrikes attributed to Mi-35s, 24 to Mi-17s, and 12 to Mi-2s. Understandably, identifying the type of jet fighter during an airstrike on civilian targets is difficult given the speed and concern for observer safety, therefore accurate aircraft type identification for fixed-wing aircraft is relatively rare. Only four types of fixed-wing aircraft are mentioned specifically in the ACLED dataset as being involved in strikes against targets in the MSM region; these include the Yak-130, MiG-29, K-8, and A-5. In 2015, the government initiated an air force modernization program to bring the MAF into the 21stCentury with modern aircraft and new facilities. Due to age and limited payloads, the Chengdu F-7 and Chengdu A-5C were largely phased out in favor of more modern alternatives such as the K-8 in 2015-2016, JF-17 in late 2017, and FTC-2000G being commissioned as of late 2024, which all fit a similar profile as the aircraft they replace.Akhil Kadidal and Andrew MacDonald, “Scorched Earth: Myanmar Air Force increases airstrikes across country,” Janes (Janes, July 3, 2023), 4, accessed April 12, 2025[25] See Table 1for information on aircraft identification characteristics.

The most notable acquisition, however, is the Yak-130 which possesses 9 hardpoints, a larger operational range at a relatively low cost, and a 3000kg maximum payload (18 in MAF).Centre for Information Resilience, “Yak-130 - Centre for Information Resilience,” November 20, 2024, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/guides/yak-130/[26]FlightGlobal, “World Air Forces Directory 2025,” Flightglobal.Com (Embraer, season-01 2025), 25, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.flightglobal.com/download?ac=106507[27] Most importantly, the Yak-130 possesses optical weapon aiming systems and liquid crystal displays for navigation, enabling operations in low-light conditions.Kadidal and MacDonald, “Scorched Earth: Myanmar Air Force Increases Airstrikes across Country,” 4.[28] However, the addition of the Yak-130 is not the only improvement the MAF has made to enhance nighttime operations. Myanmar’s Mi-35s, the MAF’s most frequently spotted/ identified aircraft in operation, received FLIR (forward-looking infrared) gimbal camera system upgrades by Russian engineers in mid-2017, enhancing the accuracy of air-to-surface missiles.NurW, “Myanmar Air Force Received the First Modernized Mi-35P Helicopter,” Defense Studies: Focus on Defense Capability Development in Southeast Asia and Oceania (blog), October 7, 2017, accessed April 12, 2025, https://defense-studies.blogspot.com/2017/10/myanmar-air-force-received-first.html[29]Ekaphom Nakphum, “Burma Air Force’s Mi-35P attack helicopter is equipped with a TV camera.: เฮลิคอปเตอร์โจมตี Mi-35P กองทัพอากาศพม่าติดตั้งกล้อง TV/FLIR ใหม่,” October 5, 2017, accessed December 19, 2023, https://aagth1.blogspot.com/2017/10/mi-35p-tvflir.html[30]

As of early 2025, the MAF is also looking to upgrade their CASC CH-3 UAVs with similar FLIR capabilities to enable low light operations, as revealed by military-published UAV footage in the IR bands acquired over rebels in norther Kachin State.Anthony Davis, “Myanmar Military Adapts FLIR Systems for Expanding Drone War,” by Janes, Janes, February 20, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-and-national-security-analysis/post/myanmar-military-adapts-flir-systems-for-expanding-drone-war[37] While night operations currently remain limited, as the Yak-130’s strikes have often resulted in significant civilian as opposed to military casualties, it is likely the more widespread deployment of FLIR technology will increase the future frequency of low-light airstrikes. It is unclear how the implementation of FLIR technology will impact the rate of civilian fatalities by airstrike. Additionally, Russia sold Orlan-10E and Orion-2 surveillance drones to Myanmar in 2024 to bolster the junta’s military operations.Davis, “Myanmar Military Adapts FLIR Systems for Expanding Drone War.”[38] Collaboration with Russia continues to prove important for the Tatmadaw, as Putin, in a March 6, 2025 Myanmar State visit to Moscow, informed the media about the recent founding of a satellite imagery analysis center in Myanmar with Russian assistance. Russia offered to share GEOINT captured by their satellites with Myanmar for military purposes.The Irrawaddy, “Eight Takeaways from Myanmar Junta Chief’s Meeting with Putin,” March 5, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/eight-takeaways-from-myanmar-junta-chiefs-meeting-with-putin.html[39] It remains to be seen how quickly the MAF will begin using their newly upgraded surveillance capabilities.

In terms of munitions, an MAF defector from Mingaladon Air Base outside of Yangon estimates “95 to 98 percent of the bombs used are locally made. While imported bombs might exist, they would only be used for critical targets under specific conditions.”DVB English Editor, “Weapons Factories Keeping Regime in Power, States Analysts,” DVB, January 23, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://english.dvb.no/weapons-factories-keeping-regime-in-power-states-analysts/[40] A 2022 OSINT investigation with BalkanInsight revealed evidence of the MAF using imported larger “cruel weapons” such as 250kg bombs and unguided rockets from Serbia.Marija Ristic et al., “Serbian Rockets Sent to Myanmar Even After 2021 Coup,” Balkan Insight (Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, February 22, 2022), accessed April 12, 2025, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/02/22/serbian-rockets-sent-to-myanmar-even-after-2021-coup/[41] Bombs weighing 250kg or more are capable of collapsing multiple floors and walls of concrete structures. Additionally, multiple reports have indicated the MAF has restarted their use of incendiary weapons, banned under the Chemical Weapons Convention that Myanmar ratified in 2015, during the Civil War.Caleb Quinley, “Anti-coup Forces Allege Myanmar Military Using Banned, Restricted Weapons,” Al Jazeera, July 2, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/7/2/anti-coup-forces-allege-myanmar-military-using-banned-restricted-weapons[42]

Additional Information on the Mi-24P/Mi-35P:

The base Mi-35 has a 450km operational range without auxiliary fuel and rockets.Yefim Gordon and Dmitriy Komissarov, Mil Mi-24 Hind Attack Helicopter (Airlife Publishing, 2001), 28–30.[43]Robert Sherman, “Mi-24 HIND (MIL),” Military Analysis Network, August 9, 2000, accessed December 17, 2024, https://man.fas.org/dod-101/sys/ac/row/mi-24.htm[44] The Mi-35P is a more heavily armed variant of the Mi-24V. The request was to replace the front-mounted machine gun with a bigger gun. The Mi-24V/Mi-35 Hind-E has a distinctly rounded front end, a large dielectric dome, unlike its predecessors.Ibid. 25.[45] The Mi-35/P both possess intake filters that allow operation in extremely dusty environments, as was needed for fighting in Afghanistan.

The cannon was mounted on the starboard side of the forward fuselage because the recoil when fired from other fixed-wing strike aircraft was too violent for rotorcraft chin mounting.Ibid. 64.[46] This meant that the pilot would have to rotate the helicopter to aim at the target, which became a liability for the Russian air force in Afghanistan. In the next evolution of the Mi-24, they opted for a rotatable cannon installation in the GSh-23L, but this mechanism was prone to jamming.Ibid. 31.[47]

Rotorcraft Identification:

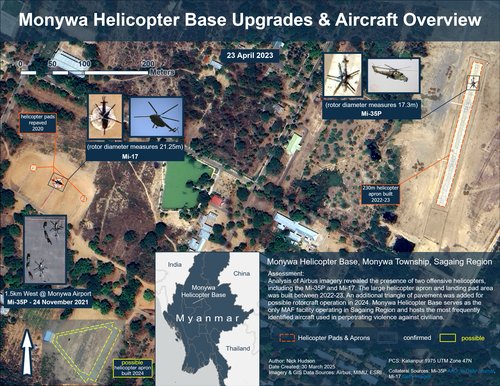

All helicopters identified in this report were identified by measuring the diameter of the rotor propeller. For example, the helicopter at the rounded landing pads in the Monywa report is determined to be an Mi-17 because of the wide, rounded shadow profile while the diameter of the main rotor was measured as roughly 21.25m.Robert Sherman, “Mi-17,” Military Analysis Network, September 21, 1999, accessed December 19, 2024, https://man.fas.org/dod-101/sys/ac/row/mi-17.htm[48]The Mi-35 has a slightly smaller rotor diameter of 17.3m and the small winglets for rocket pods are occasionally visible on both sides of the body of the helicopter.Gordon and Komissarov, Mil Mi-24 Hind Attack Helicopter, 30.[49]

Fixed-wing aircraft identification:

The A-5C was identified as it is the only aircraft Myanmar possesses with swept-back wings, flattened wingtips, a long pointed nose, and an elliptical tail configuration.Greg Goebel, Nanchang Q-5I Silhouette, January 15, 2007, Wikimedia, January 15, 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nanchang_Q-5I_silhouette.png[50] The light blue camouflaged color scheme, two engines directly underneath the fuselage with their exhaust protruding at the back, a twin tail configuration suggest the middle aircraft is a MiG-29.aviation-images.com, Mikoyan MiG-29M OVT Fulcrum Parked in the Static-Display at the 2006 Farnborough International Airshow[51] The F-7M is distinguished by a flat nose, isosceles triangular wing shape, elliptical tail shape, and brown color scheme.profilbaru.com, “List of Chengdu J-7 Variants,” n.d., https://profilbaru.com/article/List_of_Chengdu_J-7_variants[52] The JF-17 multi-role combat aircraft is identified with a single engine behind the pilot and under a 3m wide fuselage, conventional tail shape and trapezoidal wings with flattened wingtips.Shimin Gu, Pakistan Air Force Chengdu JF-17, September 3, 2017, Wikimedia, September 3, 2017, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pakistan_JF-17_(modified).jpg[53] The CASC CH-3 UCAV has a canard layout, no tail, large winglets, and a propeller located at the rear.Army Recognition, “Myanmar Armed Forces Use Chinese Armed Drones to Fight Rebels in the Country,” January 9, 2020, accessed December 19, 2023, https://www.armyrecognition.com/january_2020_global_defense_security_army_news_industry/myanmar_armed_forces_use_chinese_armed_drones_to_fight_rebels_in_the_country.html[54] The export variant of the JL-10, known as the FTC-2000G, is still heavily influenced by the MiG-21/ J-7 design but can be identified with two seats, two lateral engine intakes adjacent to the nose, leading-edge root extensions.Bradley Perrett, “Chinese Air Force Declares Supersonic Trainer Operational,” Aviation Week Intelligence Network (Aviation Week, November 9, 2015), accessed April 13, 2025[55] Finally, the K-8 has rounded low wings that begin in line with the back of the cockpit, a 9.6m wingspan, and most of the aircraft’s length being in front of the wings (including the protruding air pressure sensor).Bangladesh Air Force, Bangladesh Air Force K-8, December 2017, Wikimedia, December 2017, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bangladesh_Air_Force_K-8_(cropped).jpg[56]

Air Base Analysis

The eight MAF air bases used when striking the MSM region are Lashio, Magway, Myitkyina-Nampong, Namsang, Mandalay/ Tada-U, Shante, and helicopter bases at Monywa and Meiktila. Many of these airbases received substantial infrastructure upgrades such as larger hangars, extended or improved runways/taxiways, and new aircraft to realize the goals of Myanmar’s 2015 air force modernization program. Date ranges provided for imagery only reflect the images used in the airbase graphics and aircraft identification snapshots; larger imagery libraries outside of these date ranges were reviewed to determine aircraft presence at each base.

Lashio Air Base (22.979051°, 97.752486°)

Lashio Air Base is in North Shan State, surrounded by the Tatmadaw’s Northeast Military Command. The air base possesses a dual-purpose runway and is the smallest air base mentioned in this report with only one aircraft hangar, used primarily by rotorcraft. Analysis of Maxar multispectral imagery from 28 November 2023 and 30 January 2024 obtained through the GEGD platform in recent years exposed the frequent presence of two different types of helicopters at this air base’s military aircraft apron: the Mi-35P and Mi-17. Using mensuration via ArcGIS, it was possible to differentiate the helicopter rotor diameters which measured roughly 17.3m and 21¼m respectively. Most notably, the runway at Lashio Air Base has been extended twice in the last five years. The first runway extension added 380m of tarmac in 2020 and a second runway extension added an additional 370m in early 2024. The farmland to the immediate north of the runway was also leveled in mid-2024 but construction progress has been halted since the Brotherhood Alliance captured the Northeast Military Command and city of Lashio on August 3rd, 2024.Jack Nicholls and Nidhi Dalal, “Insight report: Re-launch of ‘Operation 1027’ underlines increasing threat of nationwide insurgency to Myanmar government’s stability in short term,” Janes (Jane’s Intelligence Review, November 22, 2024), 2, accessed April 12, 2025.[57] The main terminal at the airport in Lashio was notably damaged in October 2024 imagery of the site. A ceasefire agreement was negotiated between the junta and MNDAA in January 2025 with substantial Chinese involvement to reopen cross-border trade along Myanmar’s National Highway 3 from Mandalay to China.Morgan Michaels, “Crossing the Rubicon: Are Myanmar’s Ethnic Armies Prepared to Go All in?,” IISS Myanmar Conflict Map (The International Institute for Strategic Studies, February 2025), accessed April 12, 2025, https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2025-02[58] In late April 2025, Tatmadaw troops reentered the city of Lashio in accordance with the ceasefire while the MNDAA forces remain in control of the rural areas surrounding the city.RFA Burmese, “China Monitors Ceasefire as Myanmar Rebel Army Hands Northern City Back to Junta,” Radio Free Asia, April 22, 2025, https://www.rfa.org/english/myanmar/2025/04/22/mndaa-lashio-junta/[59] It is unclear if Lashio Air Base resumed operations since the Junta regained Lashio.

Meiktila Helicopter Base (20.888974°, 95.890169°)

Meiktila Helicopter Base is in the city of Meiktila in Mandalay Region. The base is surrounded by Myanmar’s Central Military Command and is located four kilometers southwest of the MAF’s main and largest air base, Shante. Despite its proximity to other more modern bases with paved runways, analysis of recent panchromatic Maxar imagery made available in the GEGD imagery portal supports the conclusion that this airbase is still active as of 14 December 2024. As the only runway at Meiktila has a dirt surface and no planes have been spotted in satellite imagery at Meiktila, it is unlikely the base is used by the MAF’s fixed-wing strike aircraft. The helicopters found operating from Meiktila included the Mi-17 and Mi-35P, with operation of Mi-2s designated as probable. Due to cloud cover on the imagery on the date the Mi-2 was observed at Meiktila, it was not possible to confirm identification using only the main rotor’s diameter. See the above section on Rotorcraft Identification for how the Mi-35P and Mi-17 were differentiated. Meiktila Helicopter Base provides three roughly 2900m² hangars for covered rotorcraft storage, connected to an 1800m dirt runway. The dirt runway was re-leveled and additional aircraft aprons were added between 2014 and 2015.

Shante Air Base (20.939435°, 95.913419°)

Four kilometers northeast of Meiktila and next to Tatmadaw Central Command is Shante Air Base, Myanmar’s largest air base. Analysis of Maxar imagery from Google Earth yielded significant results in identifying key aircraft used in domestic airstrikes. In April 2025 imagery, it was possible to confirm the presence of the K-8, A-5C, and Mi-17 helicopters at the airbase. Additional aircraft spotted with a level of uncertainty include the probable JF-17 and three possible Mi-2 helicopters, while a probable FTC-2000G was identified in January 2022. The A-5C was a well-equipped CAS and ground attack aircraft on arrival, needing no modifications, but is quickly being replaced by more modern aircraft.Andrew Selth, “The Myanmar Air Force Since 1988: Expansion and Modernization,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 19, no. 4 (1998): 395, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25798399[60] The MAF continues to receive spare parts for the MiG-29 and other aircraft from Russian suppliers.Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, The Billion Dollar Death Trade: The International Arms Networks That Enable Human Rights Violations in Myanmar, 13.[61] Three events designated as targeting civilians in the ACLED database specifically attribute airstrikes to fixed-wing aircraft originating from Meiktila Air Base, with one of these airstrikes attributed to a MiG-29.ACLED[62]

Minor upgrades were made to Shante Air Base’s facilities between 2019 and 2025, including the addition of a probable aircraft support facility and a large aircraft hangar. Helipads were painted onto the aircraft aprons in areas on the southern end of the airbase in 2022. Shante’s 3610m runway was repaved along with part of the taxiway and aircraft apron in the southeastern corner in 2019.

The modern aircraft observed since the February 2021 coup include the JF-17, K-8, and CASC CH-3 UCAV. While the JF-17 has experienced significant operational issues, including structural cracks and technical problems, since its delivery in 2018, several other air assets give the MAF many other ground-attack options.ANI, “Myanmar Angry With Pakistan Over ‘unfit’ Fighter Jets Supplied by Islamabad: Report,” The Economic Times, September 4, 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/myanmar-angry-with-pakistan-over-unfit-fighter-jets-supplied-by-islamabad-report/articleshow/103335997.cms?from=mdr[63] The K-8 possesses a 23mm cannon and four hardpoints capable of carrying 943kg in guided or unguided payload, fulfilling the close-air-support role.Centre for Information Resilience, “Hongdu K-8 Karakorum,” Centre for Information Resilience, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/guides/k-8/[64] In the first year and a half, the K-8 was one of the most observed aircraft behind the Mi-35, but as the civil war has progressed, the Yak-130 has supplanted its participation in a ground attack capacity.Centre for Information Resilience, “Hongdu K-8 Karakorum.”[65] The China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) CH-3, spotted on the northern aircraft apron in November 2022, is a UCAV which possesses the capability to carry and fire/ drop both AR-1 air-to-ground missile and FT-9 guided bomb.Douglas Barrie et al., “Armed uninhabited aerial vehicles and the challenges of autonomy,” The International Institute for Strategic Studies (The International Institute for Strategic Studies, December 2021), accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/globalassets/media-library---content--migration/files/research-papers/armed-uninhabited-aerial-vehicles-and-the-challenges-of-autonomy.pdf[66] There are also rumors that CASC has sold the CH-4, a externally looking copy of the MQ-9 Reaper, to Myanmar.Barrie et al., “Armed Uninhabited Aerial Vehicles and the Challenges of Autonomy.”[67]

Magway Air Base (20.154580°, 94.965747°)

Magway Air Base is in Magway Township of the Magway Region in Central Myanmar and possesses a dual-purpose runway. Analysis of recent Maxar imagery from the GEGD platform revealed the presence of offensive aircraft including the MiG-29, K-8, A-5C, and the JF-17 before structural flaws and technical malfunctions resulted in their grounding.[68] The identification of F-7BK aircraft is designated as probable given challenging shadow angles in many of the images viewed, although the mensuration yields wingspans and aircraft lengths that roughly match specifications. The F-7 is a Chinese modified version of the MiG-21 and generally considered ill-equipped for striking ground targets. According to analysis compiled by Israeli Australian military reporter Sol Salbe, the F-7s proved to be difficult for the MAF to maintain due to their high maintenance requirements and inadequate fit for the ground attack role and thus, the Tatmadaw turned to Israel for assistance.[69] Accordingly, in the following years, Israel provided laser-guided bombs while Israeli defense manufacturing company Elbit won the contract to modify the F-7 fighters.Salbe, “Israeli Military Aid to Burmese Regime: Jane’s.”[70] Within the ACLED dataset, there were two airstrikes, on February 23, 2025 and January 7, 2024, which are designated as “civilian targeting” and attributed to fixed-wing aircraft based at Magway.

Magway is another air base with improved infrastructure as part of the 2015 Myanmar Air Force modernization plan. New taxiways were built to connect the aircraft aprons and hangars at both ends of the runway in 2015 along with an additional six aircraft coverings beyond the northwestern end of the runway. These new aircraft coverings are believed to be used by the K-8 light attack aircraft which were delivered in the same year.Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “SIPRI Arms Transfers Database - Myanmar.”[71] In 2017, a large aircraft apron, support building, and the largest aircraft hangar at the base were constructed, possibly to accommodate logistics aircraft.

Monywa Helicopter Base (22.221500°, 95.093449°)

Located 12.5km north of Monywa city in Sagaing Region, Monywa Helicopter Base is surrounded by the Northwestern Military District Headquarters. Analysis of Airbus imagery from Google Earth showed the presence of two types of offensive helicopters at Monywa: the Mi-17 and Mi-35P. Uniquely, this base has no aircraft hangars to house the helicopters when they are not in use, therefore it is likely they come to the facility for rearming/ refueling before sorties. While Mi-35s have been spotted once at Monywa Airport, no additional evidence suggests that the terminal serves a fully military purpose as there are regularly scheduled flights from this airport to other cities in Myanmar every other day. Due to its proximity to the majority of Sagaing helicopter airstrike locations, MAF units based at Monywa are more likely than not responsible for the high level of civilian targeting.

In terms of infrastructure, Monywa has ample space for helicopter operations with three original landing pads (repaved in 2020) and added a 230m helicopter landing pad/ apron in 2022-2023. An additional clearing where helicopters had previously been imaged landing, south of the main three paved pads, was paved in a triangle pattern in 2024, possibly to accommodate another pair of rotorcrafts.

Myitkyina Nampong Air Base (25.353513°, 97.295557°)

Along the Irrawady River, Myitkyina Nampong Air Base is in Myitkyina Township of Kachin State, five kilometers southwest of the Northern Military Headquarters and roughly 50km west of the Myanmar-China border. Analysis of multispectral Maxar imagery between January 17, 2021 and January 5, 2024 from the GEGD imagery portal revealed the presence of several types of fixed-wing and rotorcraft believed to be stationed at Nampong Air Base, including the F-7BK/F-7IIK, K-8, Mi-35P, and Mi-17. One observation of note is the presence of a wide variety of seemingly cannibalized aircraft around the K-8 aircraft coverings at Nampong, including former F-7s, A-5Cs, while three four-rotor helicopters have been stationary south of the three main aircraft hangars for the last two years. While the K-8 was last seen at Nampong in February 2021, infrequent observations may be due to inconsistent imagery collection in recent years as Google Earth imagery consistently captured the aircraft between 2017 and 2022. As recently as January 2022, F-7s and an Mi-17 were lined up on main aircraft apron, presumably before a sortie. Mi-17s have also been observed at the airbase since 2021. The most frequently spotted aircraft at Nampong is the Mi-35P.

Nampong Air Base’s infrastructure was upgraded in 2015 to include taxiways extending to both ends of the runway and additional aircraft coverings to accommodate the delivery of new K-8 trainer/light attack aircraft. A tower-defended compound was also added adjacent to the northern taxiway junction the same year.

Namsang Air Base (20.892187°, 97.733167°)

Namsang Air Base, with a dual-purpose 3660m runway, is in Nansang Township, South Shan State. Analysis of Airbus imagery from Google Earth and Maxar imagery shot between January 13, 2020 and March 22, 2024 from the GEGD platform exposed the presence of the FTC-2000G, A-5C, and Mi-2 helicopters at Namsang. The FTC-2000G was spotted on satellite imagery at the airbase for the first time in February 2024, shortly before the new aircraft were set to be commissioned at Namsang later that Fall.The Irrawaddy, “Myanmar Junta Receives Six More Chinese Warplanes Amid Deadly Airstrikes on Civilians,” September 30, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-receives-six-more-chinese-warplanes-amid-deadly-airstrikes-on-civilians.html[72] The first round of delivery for the FTC-2000G was made in November 2022.Nyein Chan Aye, “Observers: Chinese-made Fighter Jets Play Key Role in Deadly Airstrikes in Myanmar,” Voice of America, October 11, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/observers-chinese-made-fighter-jets-play-key-role-in-deadly-airstrikes-in-myanmar/7816747.html[73] The FTC-2000G augments the junta’s striking abilities against ground targets with a 23mm cannon, four wing hardpoints, and a center hardpoint for bombs or extra fuel.Akhil Kadidal, “Myanmar Orders FTC-2000G Jets,” Janes (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 26, 2022), accessed April 12, 2025.[74] A-5Cs have also been observed taxiing near the hangars southeast of the runway. Mi-2s have been spotted several times on the aircraft apron northwest of the runway. Minor upgrades to the airbase were made, with aircraft apron expansion occurring in 2017 near the largest aircraft hangar south of the runway. North of the runway, near the rotorcraft and fixed-wing hangars, the taxiway was expanded to the passenger terminal apron.

Tada-U Air Base (21.705325°, 95.971248°)

Tada-U Air Base, sharing a runway with Mandalay International Airport, is in central Myanmar. Analysis of multispectral Maxar imagery shot between April 30, 2024 and February 26, 2025 from the GEGD platform revealed the base’s location at the southeastern corner of the 4265m runway and the existence of offensive aircraft including the K-8, Yak-130, A-5C, and Mi-35P attack helicopter. The most consistently observed aircraft at the airbase is the A-5C, spotted in imagery at Tada-U almost every year since 2014. A batch of Yak-130s was delivered to the airbase shortly after six aircraft coverings were completed early 2016.Centre for Information Resilience, “Arms Investigation: Russian Yak-130 aircraft in Myanmar,” Centre for Information Resilience, July 28, 2022, accessed December 19, 2023, https://www.info-res.org/app/uploads/2024/10/e8f7c0_ae839033f3314a0a9574460b02484b18.pdf[75] The Yak-130 is capable of being identified with cuts on the horizontal stabilizer, almost delta-shaped wings with extended wing roots, and large air intakes alongside the body of the aircraft.Centre for Information Resilience, “Yak-130 - Centre for Information Resilience.”[76] Yak-130s have been consistently observed in satellite imagery of the airbase since 2018. The K-8 with its rounded wings was first spotted at Tada-U in April 2024.

Between April 2015 and March 2016 six new aircraft coverings were constructed along with several support buildings in the following years. The airbase is one of the Tatmadaw’s most active given it is one of the most equipped bases closest to rebel-controlled area. All Tada-U’s aircraft hangars were constructed when the airbase was first commercially imaged for Google Earth in 2011.

Investigating the Destruction of Civilian Infrastructure

A total of 22 villages targeted by MAF airstrikes conducted between May 2021 and March 2025 were imaged before and after the strikes, even though 12 of these incidents had imagery that was beyond one year prior to the incident. Of these 22 instances where before and after satellite imagery existed at a resolution sufficient for damage assessment, only 9 were capable of being positively identified as damaged or destroyed based solely on satellite imagery (40.9%). The remaining 59% of buildings were unable to be confirmed as destroyed or damaged either because the building mentioned could not be found using open-source mapping services, other buildings around the location had previously been destroyed/burned, the post-strike imagery was beyond a year after the occurrence, or a combination of the aforementioned factors.

However, through this analysis, it was possible to geolocate airstrike phenomena on 60% of the village locations down to a particular building. Often it was possible to identify the purpose of buildings in a particular village using informational layers included in Google Maps and OSM.

During the analysis of satellite imagery from 50 random airstrike locations, a 7.7 magnitude earthquake hit on March 28th, 2025, 10km north of the city of Sagaing and 17km west of Mandalay (1.5 million population). Despite the earthquake and calls from numerous rebel factions in the conflict, the MAF has continued its aerial campaign against civilian and rebel ground targets alike, impeding efforts to rescue survivors across Myanmar.“Myanmar Junta Continues Airstrikes Despite Post-earthquake Ceasefire Declaration,” Global Voices, April 7, 2025, https://globalvoices.org/2025/04/07/myanmar-junta-continues-airstrikes-despite-post-earthquake-ceasefire-declaration/[77] As of April 7th, 2025, the death toll from the earthquake is 3,600 and still climbing.Edith Lederer, “Rescue Efforts From Myanmar’s Deadly Earthquake Wind Down as Death Toll Hits 3,600 | AP News,” AP News, April 7, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/myanmar-ceasefire-military-resistance-earthquake-disaster-05329d5a2448d0afd9d7c09e55a1c759[78] Any additional satellite imagery analysis of airstrikes in Myanmar would need to attempt to differentiate damage caused by the earthquake and aftershocks from bombs or rockets.

Airstrike Vector Analysis

All 1354 airstrikes in the MSM regions between March 21, 2021 and March 21, 2025 were evaluated. Although in most of the ACLED events the perpetrating aircraft is not identified, the raw data in this region provides unique insights into how the MAF wages its air campaign in the heartland of the Bamar people. ACLED’s event descriptions are condensed parts of longer articles detailing battles and atrocities in the Civil War from local news outlets.

When the aircraft type was established in the database’s entry, 44% of airstrikes were attributed to “jet” aircraft/ fighters. Aircraft that would fall into this broad category include all fixed wing aircraft in service by the MAF, including the F-7, A-5, MiG-29, K-8, Yak-130, JF-17 and FTC-2000. In a few cases these aircraft are specifically identified in the articles. 27% of airstrikes were carried out by an upgraded version of the Mi-35P Hind-F attack helicopter. Drones were the third most used type of aircraft in the first four years of the conflict. Before January 2025, the MAF was only known to use two types of drones for airstrikes, one of which is the CH-3 stationed at Shante Air Base and the other the CH-4, a Chinese Reaper UCAV replica.RFA Burmese, “Myanmar Military Adds Advanced Chinese Drones to Arsenal,” Radio Free Asia, September 27, 2024, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/military-junta-china-drones-05142024134227.html[79] Since January, the MAF has adopted a tactic from the rebel groups which use smaller drones to drop mortars on targets.“Myanmar military deploys drones to counter rebels, using greater firepower and larger scale,” interview by Um-e-Kulsoom Shariff, January 9, 2025, 00:23, accessed April 12, 2025, https://youtu.be/ODOADz-gF9s?si=jjnSV8xQcxkNF7ed&t=23[80] In 2024, Russia sold upgraded Orlan-10E and Orion-2 surveillance drones to the Tatmadaw, but the “extent to which [Russia has] assisted in the … limited development of a small first-person-view (FPV) rotary suicide drone program is unclear.”Davis, “Myanmar Military Adapts FLIR Systems for Expanding Drone War.”[81] Additionally, some aerial bombings have been attributed to piloted paragliders, a low-tech alternative to counter the frequently rebel-jammed low-altitude airspace.Ibid.[82] The next two aircraft that were most frequently identified in articles were both rotorcraft: the Mi-17 and Mi-2 were spotted in 24 and 12 airstrikes respectively. The rest of the aircraft were spotted striking targets in the MSM regions fewer than 5 times.

Of the 1354 MAF airstrikes that occurred between March 2021 and March 2025, 467 were designated “civilian targeting” in the MSM regions within the ACLED dataset. Again, in most of the strikes targeting civilians the type of aircraft was not stated. The percentage of airstrikes targeting civilians attributed to “jets” remained just above 45%, while the proportion of strikes attributed to drones accounted for a third and the Mi-35 16% where the aircraft perpetrating the violence was identified.

When the aircraft carrying out an airstrike was identified in the ACLED dataset as a “jet,” the mean distance travelled was 148 km and median 137 km to the strike location. Unlike the piloted counterparts, Tatmadaw drones went 212 km on average with a median distance of 217 km. Unlike fixed wing aircraft, the Mi-35 attack helicopter flew an average of 94 km with a median 72 km geodesic distance from base to strike location.

This raises the question whether the Myanmar Air Force travels further on average to target civilians than rebels? An OSINT investigation, leveraging social media posts, completed by Myanmar Witness on the January 7, 2024, airstrike on civilians in Kanan village of Sagaing Region, near the India border, suggests the MAF is not dissuaded from striking from afar.“Myanmar war – Airstrike and denial (who is telling the truth?) မြန်မာနိုင်ငံမှစစ်ပွဲများ,” November 21, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://vimeo.com/1031938482[83] The strike vector graphics included below display possible paths taken from the closest base to each respective airstrike location that was categorized as targeting civilians. The Kanan village airstrike by an A-5C from Tada-U is highlighted by an orange square. The mean and median geodesic distance travelled from air base to target by “jet” aircraft, including when fixed-wing aircraft are identified, are 138 km and 132 km travelled, with the leading airbase being Tada-U using the minimize weighted distance method to assign responsibility for airstrikes.

The average geodesic distance for drones to travel between base and strike point was considerably more at 210 km and a median of 214 km. Only Shante is known to host the CH-3 UAV/drone which operates at high altitudes in north-central Myanmar. The MAF has at least 10 CH-3s. The CH-4, an external copy of the US-made Reaper drone, is rumored to be manufactured and in operation in Myanmar but was not found in satellite imagery of airbases in nor adjacent to the MSM regions as of March 2025.

Finally, rotorcraft were found to average travelling 86 and a median of 62 geodesic km from airbase to village when targeting civilians. The MAF’s most used rotorcraft, the Mi-35P, was reportedly involved in 166 airstrikes in the MSM regions and 33 of these strikes targeted civilians. One of the most high-profile cases where Mi-35s were probably used against civilian infrastructure was a multi-day air campaign against Pyin Taw U village in Kale Township, Sagaing Region between March 30 and April 6, 2023.Centre for Information Resilience, “Air Attacks Damage Homes and Religious Sites in Pyin Taw U,” November 15, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/reports/air-attacks-damage-homes-and-religious-sites-in-pyin-taw-u/[84] Footage from the first day of sorties is clear enough to identify the helicopters in the sky as Mi-35s.Centre for Information Resilience, “Air Attacks Damage Homes and Religious Sites in Pyin Taw U.”[85] Shiloh Baptist Church was damaged in airstrikes where remnants of Soviet-designed S-8 rockets were found in the courtyard, according to an investigation by Centre for Information Resilience’s Myanmar Witness program.Ibid.[86] The S-8 rockets are employed by the Mi-35, attached to the stub-winged pylons, lending credibility to the claim that the MAF more likely than not used these rotorcraft to target the village.

From the strike vector graphics, several determinations can be made about the airbases used predominantly by certain aircraft types. Jet aircraft attacking targets in the MSM regions predominantly originate from Tada-U Airbase, Shante is the origin for drones, and airstrikes by the Mi-35P are likely staged from Monywa. Civilian targeting by MAF aircraft occurs from all airbases studied and no one unit is responsible for all airstrikes.

The most frequently targeted building types are typically monasteries which are generally adjacent to several tall stupas enclosed in a compound with gates facing in all cardinal directions. According to the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee in 2016, a quarter of Myanmar’s 1479 pagodas over 8.2m (27 feet) in height are in Sagaing Region, making them easy to spot for MAF aircraft.The State Samgha MahaNayaka Committee, “The Account of Pagodas and Stupas which are over 27 feet height,” mahana.org.mm, 2016, accessed April 12, 2025, http://www.mahana.org.mm/en/religious-affairs/the-account-of-pagodas-and-stupas-which-are-over-27-feet-hight/[87] 111 of 323 (34%) airstrikes that hit religious buildings were in the Mandalay, Sagaing, or Magway regions. 72 of the 208 airstrikes that impacted schools in Myanmar were in the MSM regions. Of the 107 hospitals or clinics that were damaged or destroyed in Myanmar, 33 medical buildings are in the MSM regions.

Conclusion

The Tatmadaw’s emphasis on stabilizing the situation in Myanmar through air supremacy and perpetrating violence against its own civilians warrants international attention. By upgrading MAF’s air bases, and purchasing new attack aircraft, the Tatmadaw enabled their strategy of terror and expanded their capability to conduct operations with new taxiways, extended runways, new hangars, and aircraft coverings. Now that the MAF aircraft and the bases they use have been identified, the OSINT community and people on the ground in Myanmar can continue identifying and documenting the aircraft being used to strike civilians.

Verification of a random sample of civilian infrastructure airstrike impact locations from the ACLED database using only satellite imagery proved difficult to complete due to a lack of high-resolution post-strike imagery for most of the incidents. While 22 of the 50 randomly selected strike locations had pre- and post-strike imagery, at only 9 of the villages it was possible to confirm airstrike damage to hospitals, clinics, religious buildings, and schools. However, using the village coordinates provided, the geolocation of phenomena could be enhanced to a particular building with 60% of the sample locations. There were additional cases where off-nadir imagery might have been beneficial given the MAF typically uses relatively small-sized munitions, and not all civilian infrastructure had observable roof damage below at the 50cm spatial resolution.

The distance travelled by MAF aircraft to strike rebel targets vs civilian targets is not substantially different. While the difference between all airstrikes and those designated civilian targeting when “jet” and drone aircraft were employed was less than 10 km, the MAF’s Mi-35P travelled roughly 30km shorter on average when targeting civilians. MAF units operating the Mi-35P from Monywa Helicopter Base, fixed-wing jet aircraft from Tada-U Air Base, and drones from Shante Air Base are responsible for targeting civilians most frequently in the MSM Regions. There is an expectation that the frequency of drone use in combat scenarios by the Tatmadaw will increase in 2025 as senior officials have hailed it the ‘year of the drone.’Anthony Davis, “Special Report: Myanmar’s military readies for the ‘year of the drone’,” Janes (Jane’s Defence Weekly, February 3, 2025), 1, accessed April 12, 2025.[88]

In the future, projects focusing on Myanmar could build OSINT identification profiles for airstrikes carried out by new additions to the MAF, conduct comprehensive arson mapping investigations, and expose civilian targeting while Myanmar continues to recover from the catastrophic earthquake which struck Sagaing in March 2025.

References

- Kyaw Ye Lynn, “7 Countries Still Supplying Arms to Myanmar Military,” Anadolu Agency, August 6, 2019, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/7-countries-still-supplying-arms-to-myanmar-military/1550371

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Eyes on the skies: The dangerous and sustained impact of airstrikes on daily life in Myanmar,” Centre for Information Resilience, January 27, 2023, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/reports/eyes-on-the-skies/

- Sebastian Strangio, “Protests, Anger Spreading Rapidly in the Wake of Myanmar Coup,” The Diplomat, February 8, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/02/protests-anger-spreading-rapidly-in-the-wake-of-myanmar-coup/

- Richard C. Paddock, “Myanmar coup: What to know about the protests and unrest,” The New York Times, December 9, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/article/myanmar-news-protests-coup.html

- State Administration Council (SAC), Junta, Tatmadaw, and military all refer to Myanmar state forces

- ACLED, “Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED),” Data set, Myanmar, March 21, 2025, http://www.acleddata.com/. The data downloaded from ACLED exclusively looked at events in Myanmar between February 1st, 2021, and March 21st, 2025. The only alteration of the original dataset was to add a field for date queries in ArcGIS Pro. No data were added or amended from the dataset. This applies for all other analysis sections.

- Amnesty International, “Myanmar: Four Years After Coup, World Must Demand Accountability for Atrocity Crimes,” January 31, 2025, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/01/myanmar-four-years-after-coup-world-must-demand-accountability-for-atrocity-crimes/

- “Myanmar UNHCR Displacement Overview 31 Mar 2025,” UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP), April 3, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/115466.

- Morgan Michaels, “Fighting rages along Myanmar’s transport routes,” IISS Myanmar Conflict Map (International Institute for Strategic Studies, September 2023), accessed April 12, 2025, https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2023-09.

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Impact of ‘pacify Through Fear’ Strategy From Myanmar Military - Centre for Information Resilience,” October 14, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/articles/open-source-analysis-reveals-impact-of-new-myanmar-military-operation-designed-to-pacify-through-fear/

- Centre for Information Resilience, “An Epicentre of Violence: A Sagaing Region Anthology - Centre for Information Resilience,” Centre for Information Resilience, December 31, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/reports/an-epicentre-of-violence-a-sagaing-region-anthology/

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Why Is Sagaing the Epicentre of Myanmar’s Conflict?,” February 20, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/articles/why-is-sagaing-the-epicentre-of-myanmars-conflict/

- “Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Codebook (ACLED)” (October 7, 2024), accessed June 14, 2025, https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2024/10/ACLED-Codebook-2024-7-Oct.-2024.pdf

- Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, The Billion Dollar Death Trade: The International Arms Networks that Enable Human Rights Violations in Myanmar, Online, 53rd session (UN Human Rights Council, 2023), 4, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/myanmar/crp-sr-myanmar-2023-05-17.pdf

- The $1 billion USD in imports supporting the defense industry were in amounts listed from the following countries: $406 million USD from entities in the Russian Federation, including state-owned entities; $267 million USD from entities in China, including state-owned entities; $254 million USD from entities operating in Singapore; $51 million USD from entities in India, including state-owned entities; $28 million USD from entities operating in Thailand.

- Banyar Aung, “An assessment of Myanmar’s parallel civilian govt after almost 2 years of revolution,” The Irrawaddy, August 4, 2023, https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/analysis/an-assessment-of-myanmars-parallel-civilian-govt-after-almost-2-years-of-revolution.html

- Morgan Michaels, “Is the Brotherhood headed to Mandalay?,” IISS Myanmar Conflict Map (International Institute for Strategic Studies, October 2024), accessed April 12, 2025, https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2024-09

- ACLED

- Ibid.

- Rhumbline Studio, “Classification Methods: Equal Interval, Natural Breaks (Jenks), Geometric Interval, Quantile,” October 12, 2015, accessed June 15, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ebL8OvG8Jc

- ACLED

- Clionadh Raleigh, Roudabeh Kishi, and Andrew Linke, “Political Instability Patterns Are Obscured by Conflict Dataset Scope Conditions, Sources, and Coding Choices,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10, no. 1 (February 25, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01559-4

- Richard Powell, “The Climate of Myanmar,” Blue Green Atlas, accessed April 12, 2025, https://bluegreenatlas.com/climate/myanmar_climate.html

- Ibid.

- Akhil Kadidal and Andrew MacDonald, “Scorched Earth: Myanmar Air Force increases airstrikes across country,” Janes (Janes, July 3, 2023), 4, accessed April 12, 2025

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Yak-130 - Centre for Information Resilience,” November 20, 2024, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/guides/yak-130/

- FlightGlobal, “World Air Forces Directory 2025,” Flightglobal.Com (Embraer, season-01 2025), 25, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.flightglobal.com/download?ac=106507

- Kadidal and MacDonald, “Scorched Earth: Myanmar Air Force Increases Airstrikes across Country,” 4.

- NurW, “Myanmar Air Force Received the First Modernized Mi-35P Helicopter,” Defense Studies: Focus on Defense Capability Development in Southeast Asia and Oceania (blog), October 7, 2017, accessed April 12, 2025, https://defense-studies.blogspot.com/2017/10/myanmar-air-force-received-first.html

- Ekaphom Nakphum, “Burma Air Force’s Mi-35P attack helicopter is equipped with a TV camera.: เฮลิคอปเตอร์โจมตี Mi-35P กองทัพอากาศพม่าติดตั้งกล้อง TV/FLIR ใหม่,” October 5, 2017, accessed December 19, 2023, https://aagth1.blogspot.com/2017/10/mi-35p-tvflir.html

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Eyes on the Skies: The Dangerous and Sustained Impact of Airstrikes on Daily Life in Myanmar,” 5–6.

- Janes, Scorched Earth: The role of the MAF in Myanmar’s civil war, July 2023, July 2023, accessed April 12, 2025, https://pbs.twimg.com/media/F_8KFoBXwAAf736?format=jpg&name=4096x4096

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “SIPRI Arms Transfers Database - Myanmar,” Online, Data set, March 10, 2025, https://doi.org/10.55163/safc1241

- Janes, Scorched Earth: The Role of the MAF in Myanmar’s Civil War

- The JF-17’s operational status is questionable after widespread reports of “technical malfunctions” since 2022. All the aircraft are rendered unusable despite attempts by engineers from Pakistan Aeronautical Complex to bring the planes back to operational status. The planes were most recently spotted in Maxar satellite imagery at Shante Air Base in March 2025.

- Asia Pacific Defense Journal, “Myanmar Raises Issue of Grounded JF-17 Thunder Fighter Aircraft to Pakistan,” Asia Pacific Defense Journal, September 5, 2023, https://www.asiapacificdefensejournal.com/2023/09/myanmar-raises-issue-of-grounded-jf-17.html

- Anthony Davis, “Myanmar Military Adapts FLIR Systems for Expanding Drone War,” by Janes, Janes, February 20, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-and-national-security-analysis/post/myanmar-military-adapts-flir-systems-for-expanding-drone-war

- Davis, “Myanmar Military Adapts FLIR Systems for Expanding Drone War.”

- The Irrawaddy, “Eight Takeaways from Myanmar Junta Chief’s Meeting with Putin,” March 5, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/eight-takeaways-from-myanmar-junta-chiefs-meeting-with-putin.html

- DVB English Editor, “Weapons Factories Keeping Regime in Power, States Analysts,” DVB, January 23, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://english.dvb.no/weapons-factories-keeping-regime-in-power-states-analysts/

- Marija Ristic et al., “Serbian Rockets Sent to Myanmar Even After 2021 Coup,” Balkan Insight (Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, February 22, 2022), accessed April 12, 2025, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/02/22/serbian-rockets-sent-to-myanmar-even-after-2021-coup/

- Caleb Quinley, “Anti-coup Forces Allege Myanmar Military Using Banned, Restricted Weapons,” Al Jazeera, July 2, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/7/2/anti-coup-forces-allege-myanmar-military-using-banned-restricted-weapons

- Yefim Gordon and Dmitriy Komissarov, Mil Mi-24 Hind Attack Helicopter (Airlife Publishing, 2001), 28–30.

- Robert Sherman, “Mi-24 HIND (MIL),” Military Analysis Network, August 9, 2000, accessed December 17, 2024, https://man.fas.org/dod-101/sys/ac/row/mi-24.htm

- Ibid. 25.

- Ibid. 64.

- Ibid. 31.

- Robert Sherman, “Mi-17,” Military Analysis Network, September 21, 1999, accessed December 19, 2024, https://man.fas.org/dod-101/sys/ac/row/mi-17.htm

- Gordon and Komissarov, Mil Mi-24 Hind Attack Helicopter, 30.

- Greg Goebel, Nanchang Q-5I Silhouette, January 15, 2007, Wikimedia, January 15, 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nanchang_Q-5I_silhouette.png

- aviation-images.com, Mikoyan MiG-29M OVT Fulcrum Parked in the Static-Display at the 2006 Farnborough International Airshow

- profilbaru.com, “List of Chengdu J-7 Variants,” n.d., https://profilbaru.com/article/List_of_Chengdu_J-7_variants

- Shimin Gu, Pakistan Air Force Chengdu JF-17, September 3, 2017, Wikimedia, September 3, 2017, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pakistan_JF-17_(modified).jpg

- Army Recognition, “Myanmar Armed Forces Use Chinese Armed Drones to Fight Rebels in the Country,” January 9, 2020, accessed December 19, 2023, https://www.armyrecognition.com/january_2020_global_defense_security_army_news_industry/myanmar_armed_forces_use_chinese_armed_drones_to_fight_rebels_in_the_country.html

- Bradley Perrett, “Chinese Air Force Declares Supersonic Trainer Operational,” Aviation Week Intelligence Network (Aviation Week, November 9, 2015), accessed April 13, 2025

- Bangladesh Air Force, Bangladesh Air Force K-8, December 2017, Wikimedia, December 2017, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bangladesh_Air_Force_K-8_(cropped).jpg

- Jack Nicholls and Nidhi Dalal, “Insight report: Re-launch of ‘Operation 1027’ underlines increasing threat of nationwide insurgency to Myanmar government’s stability in short term,” Janes (Jane’s Intelligence Review, November 22, 2024), 2, accessed April 12, 2025.

- Morgan Michaels, “Crossing the Rubicon: Are Myanmar’s Ethnic Armies Prepared to Go All in?,” IISS Myanmar Conflict Map (The International Institute for Strategic Studies, February 2025), accessed April 12, 2025, https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2025-02

- RFA Burmese, “China Monitors Ceasefire as Myanmar Rebel Army Hands Northern City Back to Junta,” Radio Free Asia, April 22, 2025, https://www.rfa.org/english/myanmar/2025/04/22/mndaa-lashio-junta/

- Andrew Selth, “The Myanmar Air Force Since 1988: Expansion and Modernization,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 19, no. 4 (1998): 395, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25798399

- Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, The Billion Dollar Death Trade: The International Arms Networks That Enable Human Rights Violations in Myanmar, 13.

- ACLED

- ANI, “Myanmar Angry With Pakistan Over ‘unfit’ Fighter Jets Supplied by Islamabad: Report,” The Economic Times, September 4, 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/myanmar-angry-with-pakistan-over-unfit-fighter-jets-supplied-by-islamabad-report/articleshow/103335997.cms?from=mdr

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Hongdu K-8 Karakorum,” Centre for Information Resilience, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/guides/k-8/

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Hongdu K-8 Karakorum.”

- Douglas Barrie et al., “Armed uninhabited aerial vehicles and the challenges of autonomy,” The International Institute for Strategic Studies (The International Institute for Strategic Studies, December 2021), accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/globalassets/media-library---content--migration/files/research-papers/armed-uninhabited-aerial-vehicles-and-the-challenges-of-autonomy.pdf

- Barrie et al., “Armed Uninhabited Aerial Vehicles and the Challenges of Autonomy.”

- ANI, “Myanmar Angry With Pakistan Over ‘unfit’ Fighter Jets Supplied by Islamabad: Report.”

- Sol Salbe, “Israeli Military Aid to Burmese Regime: Jane’s,” Scoop Independent News, October 2, 2007, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/HL0710/S00013.htm

- Salbe, “Israeli Military Aid to Burmese Regime: Jane’s.”

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “SIPRI Arms Transfers Database - Myanmar.”

- The Irrawaddy, “Myanmar Junta Receives Six More Chinese Warplanes Amid Deadly Airstrikes on Civilians,” September 30, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-receives-six-more-chinese-warplanes-amid-deadly-airstrikes-on-civilians.html

- Nyein Chan Aye, “Observers: Chinese-made Fighter Jets Play Key Role in Deadly Airstrikes in Myanmar,” Voice of America, October 11, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/observers-chinese-made-fighter-jets-play-key-role-in-deadly-airstrikes-in-myanmar/7816747.html

- Akhil Kadidal, “Myanmar Orders FTC-2000G Jets,” Janes (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 26, 2022), accessed April 12, 2025.

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Arms Investigation: Russian Yak-130 aircraft in Myanmar,” Centre for Information Resilience, July 28, 2022, accessed December 19, 2023, https://www.info-res.org/app/uploads/2024/10/e8f7c0_ae839033f3314a0a9574460b02484b18.pdf

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Yak-130 - Centre for Information Resilience.”

- “Myanmar Junta Continues Airstrikes Despite Post-earthquake Ceasefire Declaration,” Global Voices, April 7, 2025, https://globalvoices.org/2025/04/07/myanmar-junta-continues-airstrikes-despite-post-earthquake-ceasefire-declaration/

- Edith Lederer, “Rescue Efforts From Myanmar’s Deadly Earthquake Wind Down as Death Toll Hits 3,600 | AP News,” AP News, April 7, 2025, accessed April 12, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/myanmar-ceasefire-military-resistance-earthquake-disaster-05329d5a2448d0afd9d7c09e55a1c759

- RFA Burmese, “Myanmar Military Adds Advanced Chinese Drones to Arsenal,” Radio Free Asia, September 27, 2024, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/military-junta-china-drones-05142024134227.html

- “Myanmar military deploys drones to counter rebels, using greater firepower and larger scale,” interview by Um-e-Kulsoom Shariff, January 9, 2025, 00:23, accessed April 12, 2025, https://youtu.be/ODOADz-gF9s?si=jjnSV8xQcxkNF7ed&t=23

- Davis, “Myanmar Military Adapts FLIR Systems for Expanding Drone War.”

- Ibid.

- “Myanmar war – Airstrike and denial (who is telling the truth?) မြန်မာနိုင်ငံမှစစ်ပွဲများ,” November 21, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://vimeo.com/1031938482

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Air Attacks Damage Homes and Religious Sites in Pyin Taw U,” November 15, 2024, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.info-res.org/myanmar-witness/reports/air-attacks-damage-homes-and-religious-sites-in-pyin-taw-u/

- Centre for Information Resilience, “Air Attacks Damage Homes and Religious Sites in Pyin Taw U.”

- Ibid.

- The State Samgha MahaNayaka Committee, “The Account of Pagodas and Stupas which are over 27 feet height,” mahana.org.mm, 2016, accessed April 12, 2025, http://www.mahana.org.mm/en/religious-affairs/the-account-of-pagodas-and-stupas-which-are-over-27-feet-hight/

- Anthony Davis, “Special Report: Myanmar’s military readies for the ‘year of the drone’,” Janes (Jane’s Defence Weekly, February 3, 2025), 1, accessed April 12, 2025.

- “Enemy Air Route Channel,” Telegram, n.d., https://t.me/enemyairroute

- MyanmarWitness, “Claims Recently Emerged Online That a Myanmar Air Force Helicopter Fired on a School Where IDP Children Were Studying on 10 September 2023 in Yinmarbin Township, Sagaing Region.,” Twitter/ X, September 14, 2023, accessed November 26, 2023, https://x.com/MyanmarWitness/status/1702358822499553420?s=20

- MyanmarWitness, “Claims Recently Emerged Online That a Myanmar Air Force Helicopter Fired on a School Where IDP Children Were Studying on 10 September 2023 in Yinmarbin Township, Sagaing Region.”

- Su Mon, “Q&A: Will the Ceasefires After the Earthquake Bring Peace to Myanmar?,” ACLED, April 25, 2025, accessed May 6, 2025, https://acleddata.com/2025/04/24/qa-will-the-ceasefires-after-the-earthquake-bring-peace-to-myanmar/

- Mon, “Q&A: Will the Ceasefires After the Earthquake Bring Peace to Myanmar?”

- Ibid.

Look Ahead

The time it took to complete this report spanned roughly 6-7 months of cumulative work over a year-and-a-half period related to establishing the type of geospatial report that would be created, devising a color palette for the creation of maps, icon creation, searching libraries and downloading imagery, identifying aircraft, digitizing airbase upgrades, verifying strike locations, separating datasets by aircraft/ civilian targeting, and many other functions. If another analyst was to repeat this type of analysis in another country, it would be possible to complete a similar report in 4-5 months with an aggressive timeline. For future analysts, the percentage of time spent envisioning the report's focus was 10%, 35% spent on discovering, 25% spent comprehending, 10% tracking new <50cm spatial resolution imagery added to libraries, and 20% reporting findings. I recommend a similar blend of time spent on these tasks if the analysis were replicated in another region or country. The workflow that was implemented for this project leveraged imagery libraries from the GEGD Maxar and Google Earth platforms and utilized ArcGIS Pro for statistical analysis and map creation. While the Maxar library was made available to the researcher at no cost, another team working independently of Tearline would need to fund a large imagery bill through a site that permits the purchasing of imagery slices such as UP42. Ideally, future analysis in this conflict zone should leverage a larger library of commercially available satellite imagery, explore a host of available Telegram channels covering the conflict like “enemyairroute” and MyanmarWitness, and join local Facebook groups documenting atrocities.[89][90][91] Since the March 28 earthquake that struck central Myanmar there have been four ceasefires negotiated, two of which were extended.[92] However, without robust ceasefire enforcement mechanisms and the continuation of junta-enforced limitations on internet access and the transport of humanitarian aid to impacted regions, there is no clear path to a resolution.[93] The MAF continues to wage an aerial campaign against civilians, a pattern that increased in intensity after the Brotherhood Alliance launched Operation 1027 in late October 2023, resulting in significant territorial losses for the Tatmadaw.[94]

Things to Watch

- Can future airstrikes against civilian targets that appear in the news be geolocated from OSINT imagery or videos posted on Facebook or Telegram?

- Will international aid groups operating in Myanmar be targeted by MAF airstrikes as they help earthquake victims in rebel-controlled territories?