Overview

Although North Korea officially announced the closure of Kwan-li-so No. 18 in 2006, commercial satellite imagery analysis indicates that the camp has not been completely razed. Imagery analysis further indicates that the remaining facility, whether officially designated as such or not, is a large and active detention facility.

The Kwan-li-so No. 18 area remains active and is well-maintained, as indicated by numerous agricultural, light industrial, and mining activities.

Activity

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) to use satellite imagery and former detainee interviews to shed light on human suffering in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK, more commonly known as North Korea) by monitoring activity at political prison facilities throughout the nation.

Facility Analysis

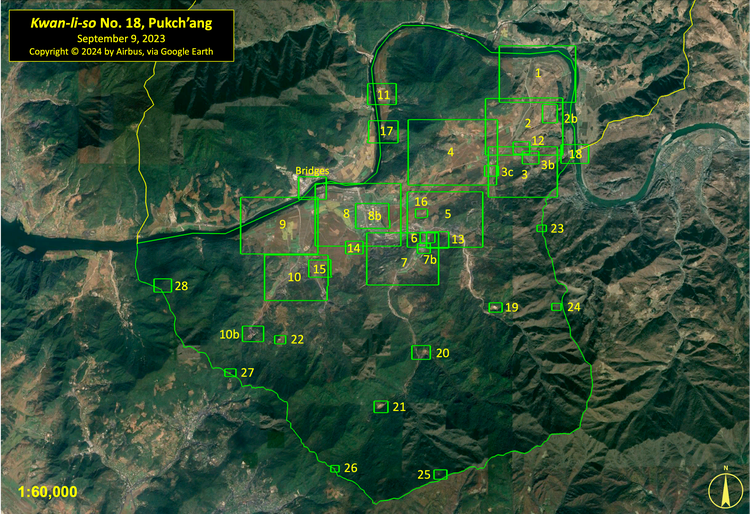

Location: Pukch’ang-gun, P’yŏngan-namdo (Pukch’ang County, South Pyongan Province)

CenterPoint coordinates: 39.552435°N, 126.073063°E

Date of Imagery Used: September 9, 2023 (Airbus, via Google Earth), January 25, 2024 (Maxar)

Size of Original Facility: approximately 71.5km2 (11.5 km by 11.2 km)

Executive Summary

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former prisoner interviews to shed light on human suffering in North Korea by monitoring activity at political prison and other detention facilities throughout the nation.Previous reports in the project can be found at: https://www.hrnk.org/publications/hrnk-publications.php.[1]

Specifically, this is HRNK’s first satellite imagery report concerning a prison facility commonly identified by researchers and former prisoners as Kwan-li-so No. 18 (Political Penal-Labor Colony No. 18, “Camp No. 18,” or Pukch’ang Detention Camp). While this report provides a preliminary overview of major changes that have occurred at this facility in the past ten years, it also provides more general analysis dating back to 2004.For additional information concerning Kwan-li-so No. 18 from 2003 through 2013, please see HRNK’s Hidden Gulag series of reports by David Hawk: The Hidden Gulag: Exposing North Korea’s Prison Camps (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2003). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/The_Hidden_Gulag.pdf (hereafter: HG1); The Hidden Gulag: The Lives and Voices of “Those Who are Sent to the Mountains” (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2012). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_HiddenGulag2_Web_5-18.pdf (hereafter: HG2); North Korea’s Hidden Gulag: Interpreting Reports of Changes in the Prison Camps (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2013). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/NKHiddenGulag_DavidHawk(2).pdf (hereafter: HG3).[2]

This analysis supports previous HRNK and media reports that, in response to a number of prisoner escapes and subsequent international attention, the North Korean authorities initiated a public closure of Kwan-li-so No. 18 in 2006. In subsequent years, prisoners were released or transferred to other camps.Hawk, HG1, 24–25, 36–38, 101–08; Parliament of Canada, Subcommittee on International Human Rights of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, Number 40, 3rd Session, 40th Parliament, Testimony of Kim Hye-sook, February 1, 2011. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/403/SDIR/Evidence/EV4916717/SDIREV40-E.PDF; Hawk, HG2, 27, 48, 70–77, 216–21; Hawk, HG3, 23–33; Han Dong-ho et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2014 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, July 2014), 139–43; Do Kyung-ok et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2015 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, September 2015), 80–84; Do Kyung-ok et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2016 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, April 2016), 79–81; UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, UN Doc. A/HRC/25/CRP.1, February 7, 2014, 65–66, 199; 2015 White Paper on North Korean Human Rights (Seoul: Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, December 2015), 426.[3] Some of those released reportedly elected to stay within the area of the former camp under some level of civilian administration, rather than returning to their hometowns or cities.Ibid.[4]

According to Hwang Jang-yop, the highest-ranking North Korean official to ever defect to South Korea, the detention facility for what would eventually become Kwan-li-so No. 18 was first established at the Pukch’ang mine in 1958.Lee Keum-soon et al., Bukhan jeongchibeom suyongso [North Korea’s Political Prison Camps] (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, 2013), 17. https://repo.kinu.or.kr/bitstream/2015.oak/2246/1/0001459195.pdf.[5] A former prisoner testified that many individuals targeted by the Sim-hwa-jo campaign, including the purge of Agricultural Secretary Seo Kwan-hee in 1997, were imprisoned at the camp.Written testimony obtained by HRNK. The 1997 Sim-hwa-jo incident, also known as the Sim-hwa-jo Sa-eop (Intensification Operation), was a massive purge of many of Kim Il-sung’s close associates, their institutional support structure, and family members. The goal of this purge was twofold: to replace the old power base with Kim Jong-il loyalists, and to identify and blame scapegoats for the catastrophic policy failure that resulted in the great famine and humanitarian disaster of the 1990s. Eventually, the Public Security Department (later known as the Ministry of People’s Security, currently known as the Ministry of Social Security) incarcerated or executed over 30,000 officials and family members. See Ken E. Gause, Coercion, Control, Surveillance, and Punishment: An Examination of the North Korean Police State, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2013), 59, 131–35. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_Ken-Gause_Translation_5_29_13.pdf.[6] Recent reports suggest that officials purged during Kim Jong-un’s rule, as well as the family members of these officials, may have been sent to Kwan-li-so No. 18.Mun Dong-Hui, “Kim Jong Un reopens political prison camp to house political enemies,” Daily NK, January 9, 2024. https://www.dailynk.com/english/kim-jong-un-reopens-political-prison-camp-house-political-enemies/.[7]

After its establishment, the camp was expanded and continued to operate at a high level until about 2006, when the process of closure began.Hawk, HG1, 24–25, 36–38, 101–08; HG2, 27, 48, 70-77, 216–21; and HG3, 23-33.[8] Despite repeated official and unofficial statements since then that Kwan-li-so No. 18 has been completely deactivated, satellite imagery analysis indicates that significant elements remained operational until about 2012–13, when major sections of the camp began to be razed.

This process, however, did not completely close the camp. New walled facilities, guard barracks, and perimeter guard positions in remote mountainous areas were erected, all within the borders of what was previously known as Kwan-li-so No. 18. This process of razing old facilities and expanding or building new facilities continued through 2016–2017, when it dropped off significantly. Smaller changes have continued until early 2024, indicating that the camp (or its successor organization) remains active, albeit at a reduced level compared to its predecessor.

Whether the official designation of this facility remains Kwan-li-so No. 18 is unknown. A new designation may—in a semantic sleight of hand—allow the North Korean regime to claim that the facility has been deactivated. It is likely that a subset of former detainees has been moved into these new detention facilities.

It is not currently practical to distinguish the areas that are being utilized as detention facilities from those being used for nominal civilian purposes. For ease of comprehension, this report will refer to the entire area as Kwan-li-so No. 18 until more up-to-date information about its detailed organization and official designation(s) become available.

HRNK anticipates that it will be able to develop a more complete understanding of the development and status of Kwan-li-so No. 18 and any successor organization(s) when former prisoners and other North Korean citizens with direct knowledge of the camp are able to provide additional testimony.

As with the analytical caution presented in previous HRNK reports, it is important to reiterate that North Korean officials, especially those within the Korean People’s Army (KPA), Ministry of State Security, and Ministry of Social Security, clearly understand the importance of implementing camouflage, concealment, and deception (CCD) procedures to mask their operations and intentions.Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., Greg Scarlatoiu, and Amanda Mortwedt Oh, North Korea’s Political Prison Camp, Kwan-li-so No. 14, Update 1 (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, December 22, 2021). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Camp%2014%20v.8.pdf.[9] It would not be unreasonable to assume that they have done so at this facility.

Overview

For this report, HRNK reviewed high-resolution commercial pan-sharpened multispectral satellite images of Kwan-li-so No. 18 and its immediate environs, with a focus on the following features.The term “high resolution” in this report refers to digital satellite images with a ground sample distance (GSD) of less than 1 meter. The GSD is the distance between pixel centers when measured on the ground. Analog (film) satellite imagery is measured in ground resolution.[10]

- Security perimeters (internal and external), entrances, and guard barracks and positions

- Headquarters, administration, and support facilities

- Housing, agricultural, and agricultural support facilities

- Mining and forestry activity

- Internal road network

- Light industrial facilities

- Railroad network

- Bridges, fords, and ferry crossings

Based on this analysis of key features, it is clear that large sections of Kwan-li-so No. 18 were deactivated over a period of at least eight years and that smaller sections remain active as a detention facility. It is equally clear that access to the former camp remains physically restricted and a security perimeter is being actively maintained. Thus, any personnel within this security perimeter are unlikely to have the freedom of movement or access to services and resources as the average North Korean. Significantly, satellite imagery indicates that elements of the former camp, including some in remote, mountainous areas, appear to remain active as a political prison facility.

Satellite imagery coverage of the facility and former detainee testimony indicate that the prison’s economic activity is a combination of agricultural production and mining, with some instances of light industry. It is not currently possible to determine the division of labor between those individuals who have been released but remain within the deactivated areas of the camp, and those who are still being held as prisoners within the active elements of the camp.

HRNK is presently unable to estimate the number of people remaining within the deactivated sections of the camp or those held within the active areas of the camp.

Location

Kwan-li-so No. 18 is located approximately 66 kilometers northeast of the capital city of P’yongyang, approximately 25 kilometers southeast of the city of Kaech’on, and primarily within Pukch'ang-gun (Pukch'ang County). It occupies an irregularly shaped area that measures approximately 11.5 kilometers by 11.2 kilometers (7 miles by 7 miles), encompassing approximately 71.5 km2 (27.6 mi2), with nine named villages and numerous unnamed villages. The northern perimeter of the camp is the Taedong-gang (Taedong River), which separates it from Kwan-li-so No. 14, located on the north side of the river. The southern perimeter consists of a fence and patrol path on the slopes of Satkat-pong (Satkat Peak).

Subordination and Organization

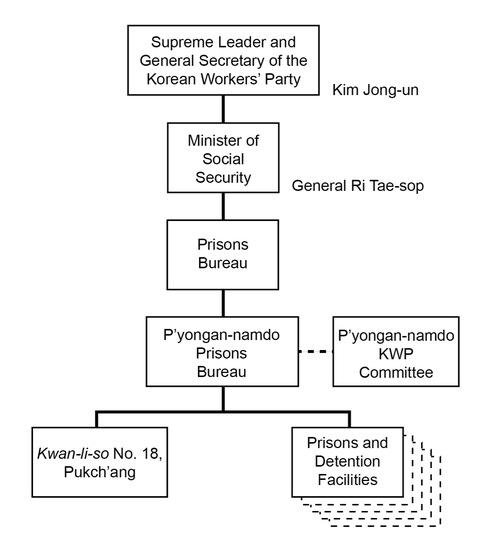

The best available information indicates that Kwan-li-so No. 18 has been and remains an anomaly among North Korea’s Kwan-li-so. Camp No. 18 is operated by the Ministry of Social Security (formerly the Public Safety Department and Ministry of People’s Security), rather than the Ministry of State Security (formerly the State Security Department).The Ministry of People’s Security is reported to have changed its name to the Ministry of Social Security around 2020. Jeongmin Kim, “North Korea likely renames Ministry of People’s Security, NK News, June 3, 2020. https://www.nknews.org/2020/06/north-korea-likely-renames-ministry-of-peoples-security/?t=1591178315505; and “평양종합병원건설장으로 달려오는 마음,” Ryugyong, June 2, 2020. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1591084868-679913493/%ED%8F%89%EC%96%91%EC%A2%85%ED%95%A9%EB%B3%91%EC%9B%90%EA%B1%B4%EC%84%A4%EC%9E%A5%EC%9C%BC%EB%A1%9C-%EB%8B%AC%EB%A0%A4%EC%98%A4%EB%8A%94-%EB%A7%88%EC%9D%8C/.[11] This has meant that it has operated as a less strict and severe prison facility compared to other Kwan-li-so, which are all run by the Ministry of State Security.

However, this does not diminish the cruelty and severity of the human rights abuses committed at Kwan-li-so No. 18. Some of these abuses amount to crimes against humanity, according to the UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) on human rights in North Korea. It was reported that the camp had a prisoner population of approximately 50,000, including the families of the prisoners, in the early 2000s. Of this population, approximately 30,000 were organized into work teams, while the remaining 20,000 were children and elderly relatives.Hawk, HG1, 38.[12] However, another source indicates that by 2020, the detainee population of Kwan-li-so No. 18 had fallen to 24,000.Mun Dong-Hui, “The number of inmates in North Korean political prisons have increased by at least 20,000 since March 2020,” Daily NK, July 28, 2021. https://www.dailynk.com/english/number-inmates-north-korean-political-prisons-increased-at-least-20000-since-march-2020/.[13] Notably, there have been intermittent reports indicating that areas of the camp have continued to operate as a detention facility.For example, see Blood Coal Export from North Korea: Pyramid scheme of earnings maintaining structures of power (Seoul: Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights, 2021), 58–61. https://www.nkhr.or.kr/en/publications/nkhr-research-reports/blood-coal-export-from-north-korea-pyramid-scheme-of-earnings-maintaining-structures-of-power/.[14]

HRNK is unable to independently confirm reports about the size of the prisoner population with any level of accuracy. Additionally, due to a paucity of detailed and reliable information, HRNK is not in a position to either confirm these earlier numbers or to present a reliable estimate of current prisoner population at Kwan-li-so No. 18.

The Ministry of Social Security and its minister, General Ri Tae-sop (리태섭), report directly to Kim Jong-un as the Supreme Leader and General Secretary of the Korean Workers’ Party (KWP).For a comprehensive discussion of North Korea’s prison camp command-and-control structure, see Robert Collins, “Control of the Kim Regime’s Political Prison Camps,” HRNK Insider, November 28, 2016. http://www.hrnkinsider.org/2016/11/control-of-kim-regimes-political-prison.html. Collins states, in part: “These political prison camps started with the early Kim Il-sung regime’s concept of banishment of those deemed enemies of the party and state—religious persons, landowners, businessmen, those that cooperated with the Japanese colonial government in Korea, and even those deemed too popular locally—to North Korea’s mountainous northeast. These banishments developed into the current form of actual political prisons concurrently with the development of the Ten Principles of Monolithic Ideology.”[15] The Ministry of Social Security has reportedly had eight ministers since 2010: Chu Sang-song (2004–11), Ri Myong-su (2011–13), Choe Pu-il (2013–19), Kim Jong-ho, Ri Yong-gil, Pak Su-il, Chang Jong-nam, and Ri Tae-sop.Based on search results from 'North Korea Information Portal,' Republic of Korea Ministry of Unification. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://nkinfo.unikorea.go.kr/nkp/prsn/view.do.[16] It is notable that Choe Pu-il, a former Minister of Social Security, is under U.S. sanctions.Also known as Choe Pu Il or Ch’oe Pu-il. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “North Korea Administrative Designations Updates,” May 13, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/recent-actions/20200513.[17]

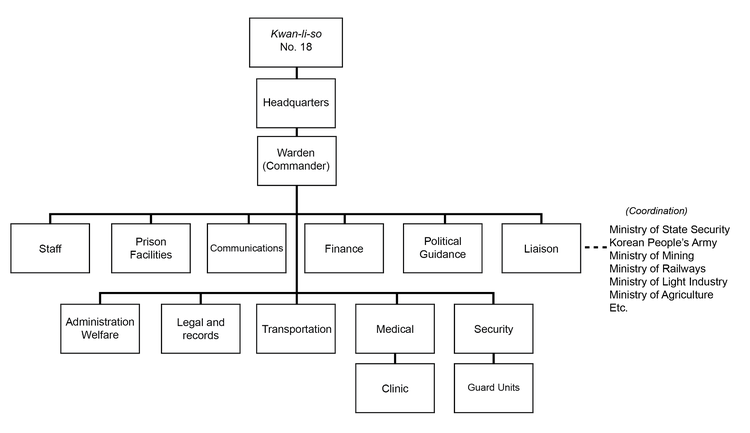

Based on open-source information and known North Korean organizational patterns, Kwan-li-so No. 18 is likely to be organized along a somewhat standard pattern—probably similar to, but an enlarged version of that seen at kyo-hwa-so (long-term prison-labor facilities). Such an organization would likely consist of a headquarters staff, communications section, finance section, political guidance section, legal and records, administration and welfare section, liaison section (Ministry of State Security, KPA, South Pyongan Province KWP Committee, and various ministries), transportation section, safety/medical section, and a security section (guard unit). The nature of the coordination between the camp and the ministries is uncertain.

The area encompassing Kwan-li-so No. 18 was historically involved in agricultural production (e.g., fruit orchards, beans, potatoes, corn) and coal mining. Over the years, light industrial activities were introduced, and coal mining increased dramatically. Since the closure process of the camp began, agricultural activity appears to have continued at previous levels, while coal mining and light industrial activities appear to have decreased slightly.

Functionally, the majority of villages and agricultural and light industrial activities are located near the northern area, while mining activities are located in the central and southern areas. Former prisoners report that activities within the camp were organized into work “units” or “divisions” that were geographically separated and arranged by type (e.g., agriculture, mining, and light industry).Hawk, HG2, 216–21.[18]

For analytical purposes, this report divides the camp into 28 discrete areas depicting specific activities or that are representative of more general activities. Former detainees report that the camp contained a small “revolutionizing zone” for prisoners who were eligible for release back into society and a “liberation zone” where prisoners were allowed additional privileges.Ibid., 70.[19] The precise locations of these zones are unknown, however.

Electric power for both the deactivated and remaining sections of the camp is likely provided by both the hydroelectric power plants across the Taedong-gang (1 kilometer west of Chamsang-ni) and by local generators. Likewise, both areas are connected to the national rail network via the Pongch’ang-ni railroad station and the various coal loading stations south and southwest of the station. The closest air facility is the Korean People’s Air Force Pukch’ang-ni Airbase, 11.6 kilometers to the southwest of Pongch’ang-ni. This base is home to MiG-23 and MiG-29 air regiments. Due to its mission, organization, and location, it provides no support to the camp.

Camp Perimeter, Security Facilities, and Entrances

Kwan-li-so No. 18 encompasses 71.5 km2, enclosed within an approximately 39.5 kilometer-long security perimeter consisting of five entrances connected by patrol paths and roads. The perimeter is secured by at least 13 identified guard barracks, perimeter remote guard barracks, and perimeter guard positions, 8 of which were constructed after 2013 and the camp’s reported closure in 2006. Supplementing these guard facilities are an estimated 35 to 40 small guard posts scattered around the camp, along the Taedong-gang, and internally throughout the camp. Facilities used by the Ministry of State Security, as well as a paramilitary reserve training facility, are not included in these numbers.

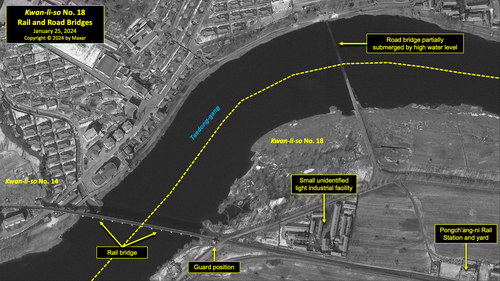

There are five entrances that control access to Kwan-li-so No. 18. The primary entrances are located along the north side of the camp across the Taedong-gang. These include a rail bridge, a road bridge, and a ferry point, all of which cross directly into Kwan-li-so No. 14.

- The rail bridge connects Kwan-li-so No. 18’s Pongch’ang-ni Rail Station and yard, and the Pongch’ang-ni and Yŏngdŭng coal loading stations to the national rail system through the Yasach’am Rail Station in Kwan-li-so No. 14.Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., Andy Dinville, and Mike Eley, North Korea Imagery Analysis of Camp 14 (Washington, D.C.: HRNK, 2015), 4, 14–16, 48, 61–62. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/ASA_HRNK_Camp14_v7_highrezFINAL_11_30_15.pdf.[20]

- The road bridge is 500 meters northeast (upstream) of the rail bridge. It is sometimes incorrectly referred to as an “underwater bridge” or “reinforced ford,” as the elevated water levels of the Taedong-gang during spring and summer flow over the top of the bridge, making it impassable.Ibid.[21]

- Located on the Taedong-gang, 2.5 kilometers northeast (upstream) of the road bridge, is a ferry crossing connecting Kwan-li-so No. 14 to Kwan-li-so No. 18. The crossing was built sometime between 2007 and 2011 and consists of an entrance checkpoint, landing ramps on both sides of the Taedong-gang, and a 12 meter-long ferry. This ferry crossing was likely built to support the activities of a sand/gravel quarry located 200 meters to the south.Ibid.[22]

Secondary entrances are southwest of the Hanjae mine and east of the Sang-ni Orchard Village.

- Located 1 kilometer southwest of the Hanjae mine is the Hallyŏng Southwest perimeter guard position and entrance. A small dirt road connects Kwan-li-so No. 18 to the coal mining town of Hallyŏng-ni, 1 kilometer to the southwest. The dirt road is useable by light vehicles and foot traffic.

- The final entrance is located on the extreme east side of the camp on the Taedong-gang, approximately 900 meters east of the Sang-ni Orchard Village. It controls access to a dirt and gravel road connecting Kwan-li-so No. 18 to the coal mining town of Myonghak-dong to the south.

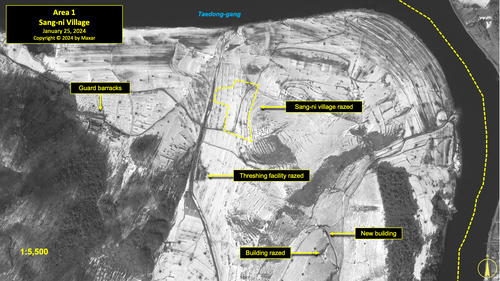

Area 1. Sang-ni Village

Sang-ni is located in the northeast corner of the original camp on the southern bank of the Taedong-gang. It consists of several small villages and is associated with various agricultural activities.

There have been substantial changes to the village and general area during the past ten years. Among these were the razing of the village, consisting of approximately 37 structures and eight additional structures in the general area, in 2016. The threshing complex (eight structures in total) serving the village and three nearby small buildings were also razed. Six small unidentified buildings were constructed in the area from 2016 to 2023.

Approximately 500 meters west of the former village is what appears to be a guard compound partially surrounded by a security wall with four guard positions that encompasses approximately 0.3 hectares that was built sometime between 2007 and 2011. Since then, it has continued to be slowly developed with sheds, a partially paved courtyard, and a small building. Several small out-buildings adjacent to the compound have been razed, built, or rebuilt in the past five years.

Additional minor changes have been observed in this area since 2013.

Area 2. Sang-ni South

Although the village historically identified as Sang-ni was razed in 2016, an unnamed, larger village located approximately 1 kilometer to the south-southeast is visible in all available satellite imagery. Given the common practice in North Korea of naming groups of small villages (especially farming villages) using the same name, it is likely that this village is also known as Sang-ni. For clarity, this report will identify it as Sang-ni South.

On October 1, 2013, the village consisted of approximately 35 housing and agricultural structures including a threshing facility and a guard position. During 2018–19, there was a reorganization of the housing areas in the village. Housing units were razed, rebuilt, and walled in. The housing units in this area are divided into two distinct walled compounds, with a guard position centrally located between the two. There is a threshing facility at the south side of the village. Various smaller changes have occurred in and around the village during the past ten years. As of January 25, 2024, there were 44 structures overall.

Approximately 1,100 meters to the west-southwest of Sang-ni South is a walled compound identified by a former detainee as a KPA Paramilitary Reserve Training Unit facility.Also known as a “Reserve Military Training Unit (RMTU).” Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; also David Hawk interview data with Kim Hye-sook, July 2016, Seoul, Republic of Korea (hereafter: Hawk Interview).[23] This facility encompasses approximately 2 hectares (of which approximately 1.4 are walled) and consists of approximately 13 structures. It is visible in all commercial satellite imagery since 2007.

During 2016, a new agricultural complex was constructed 800 meters to the southeast of the paramilitary reserve training facility. In total, eight buildings were constructed, including a threshing building and two greenhouses. The complex has been gradually enlarged and consisted of approximately 20 structures as of January 25, 2024.

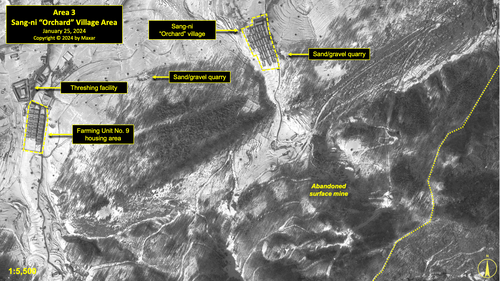

Area 3. Sang-ni Orchard Village

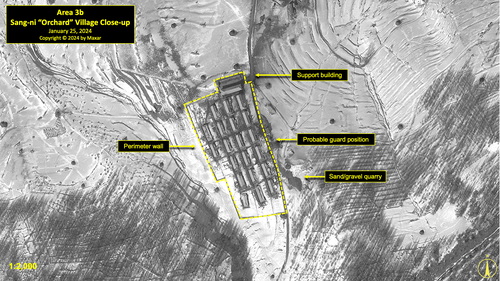

Approximately 175 meters south of the Sang-ni South village is a small village identified as the “Sang-ni Orchard Unit” by a former detainee because of the small orchards in the area.Hawk Interview.[24] The village is present in all available commercial satellite imagery and has experienced minor changes over time.

In 2013, the village contained 22 houses aligned on the west side of the village road, with a single guard position on the east side of the road. During March 2016, a large support facility was added on the north side of the village. While there was formerly a guard position and partial walls in and around the village, a walled perimeter was erected sometime around 2019. This perimeter enclosed an area of about 1.73 hectares, with two guard positions—one on the north side and another on the south side. During 2021–23, this perimeter was reduced, and a greenhouse was added. As of January 25, 2024, the village encompassed 1.4 hectares and consisted of approximately 24 structures, including two guard positions and a greenhouse.

Adjacent to the village, on the east side, is a sand quarry that has been present since 2007. A second sand quarry located approximately 500 meters west of the village was established during 2016–17. As of January 25, 2024, both were active at a low level.

Located in the hills south of the south of the Sang-ni Orchard Village is a large, abandoned surface coal mining area, where at least 11 buildings were razed during 2016–17. While numerous mining haul roads and tailings piles remain visible throughout the area, no new building activity, enlarged tailing piles, or vehicle activity can be seen in available commercial satellite imagery. This suggests that the mine has been closed and abandoned.

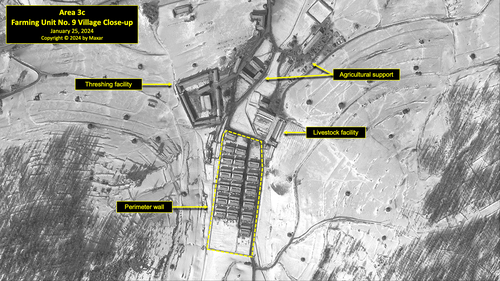

Approximately 950 meters west of the Sang-ni Orchard Village is a compound identified by a former detainee as Farming Unit No. 9. In 2013, it consisted of 64 structures including a threshing facility and greenhouses and encompassed an area of approximately 5.5 hectares. By 2016, 16 structures had been razed. Between 2017 and 2020, an additional 32 of the original structures were razed. However, in the same time frame, 15 new houses were constructed, and a perimeter wall was built around them, enclosing a total area of 4.3 hectares, of which 1.3 hectares is walled housing. No further significant changes could be identified until the most recent imagery of January 25, 2024.

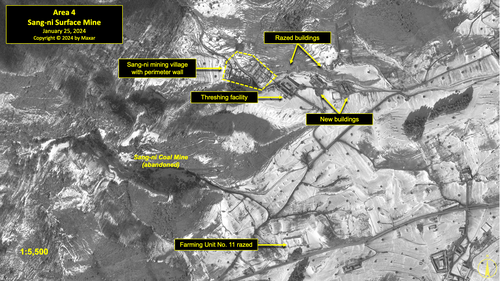

Area 4. Sang-ni Surface Mine

To the west of the Sang-ni Orchard Village and Paramilitary Reserve Training Unit compound are what have been identified by a former detainee as the Sang-ni Surface Mine, Farming Unit No. 11, and a small unnamed village.Ibid.[25] Between 2007 and 2013, the Sang-ni Surface Mine showed little discernible activity. By March 2016, the last remaining building at the mine had been razed. No activity of significance has been noted since, and the coal mine has been abandoned.

Approximately 490 meters northeast of the Sang-ni Surface Mine is a small unnamed village. In 2013, it consisted of 60 structures including housing units, threshing facility, greenhouses, and other agricultural related buildings. By 2016, thirteen houses had been razed and the threshing facility rebuilt. Fourteen more houses were razed and ten rebuilt between 2017 and 2020. A perimeter wall was built between 2017 and 2019, partially enclosing a total of 29 houses. It appears that at least one guard position was added during 2019–20, but it is no longer present in 2024.

This village is likely a component of Farming Unit No. 11, as it is adjacent to the relatively large open agricultural area south of the Sang-ni Surface Mine that a former detainee has identified as Farming Unit No. 11.

In 2007, a small compound was located in the middle of this open agricultural area. This partially walled compound consisted of four buildings arranged around a central courtyard. By 2011, two buildings had been demolished and a wall had been constructed around the compound, enclosing an area of 0.95 hectares. Sometime between 2014 and 2016, the compound started to be razed. The last vestiges of this compound were fully removed between 2018 and 2019.

Approximately 470 meters south of this compound and across a road was a small group of buildings that were likely also part of Farming Unit No. 11. In 2013, there were 12 buildings. Of these buildings, eight were demolished by 2016 during the same time period as the above compound. A further two were demolished by 2019, and the remaining two buildings were rebuilt and enclosed by a wall, along with a small, new building.

During 2007–11, a small walled compound was built 900 meters north of Farming Unit No. 9, in the same open agricultural area identified as Farming Unit No. 11. This compound, encompassing approximately 0.17 hectares, showed no significant changes until the most recent image of January 25, 2024.

Most recently, during 2017–19, the main road running through the area was rebuilt, straightened, and resurfaced.

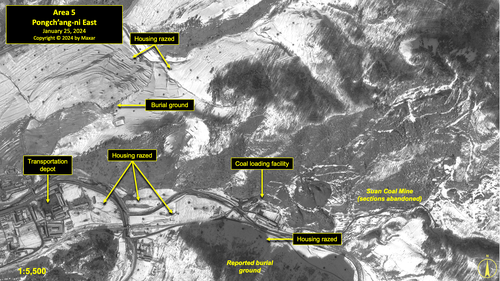

Area 5. Pongch'ang-ni East

Pongch’ang-ni is the administrative and industrial center of Kwan-li-so No. 18. Aside from detainee and civilian housing areas located in the eastern section of the town, there are several guard positions, three coal mines (Suan Mine, Gingol Mine, and Pongch’ang Mine), a coal loading station for trucks, a Ministry of Social Security compound, a mining tools factory, a threshing facility, and a motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility in the area.Ibid.[26] A former detainee has tentatively identified two high explosives (used for mining) storage structures and a burial ground in the area.

In 2013, this area contained five housing sections. Between 2013 and 2019, a total of about 93 houses were razed in this area. On November 9, 2020, there were approximately 45 houses. By January 25, 2024, there were only 38 remaining. Two of these housing sections (one next to the motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility and one south of the explosives storage area) had perimeter walls added between 2017 and 2019.

Located in the eastern section of Pongch’ang-ni are the motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility and a small mine tools shop. The site was partially renovated in 2016–17, but largely retains the same layout as it did in 2013.

A former detainee reports that a Ministry of State Security compound is located 200 meters northwest of the motor vehicle depot. According to former detainee testimony, a small detention facility exists within the compound. The roofs of four of the buildings were replaced between 2019 and 2020. Although some minor changes took place, the compound essentially remained unchanged between 2020 and 2024.

The Suan Coal Mine has seen continuous activity in all imagery since 2007. Its eastern section appears to have been abandoned around 2013 and its support buildings razed. The remaining western section of the mine, including the loading depot, underwent changes during 2016–17 and again during 2019–20. There were no significant changes between 2020 and 2024. A former prisoner testified that the family of Kim Yong-suk, Kim Il-sung’s sister-in-law, was brought to Kwan-li-so No. 18 in 1993 and worked at the Suan Mine.Written testimony obtained by HRNK.[27]

Farming Unit No. 9 is reported to be located in and around the village of Samp’o-dong (sometimes identified as the “New Village”).This is the same 'Farming Unit No. 9' that is referenced in Area 3. According to a former detainee, structures associated with Farming Unit No. 9 are located at both ends of a broad and fertile farming area that stretches between Areas 3 and 5. The structures associated with Farming Unit No. 9 in Area 5 are in the top-left corner of the image, under the title box.[28] This unit is engaged in both agricultural work in the surrounding fields and raising small livestock (pigs). Between 2013 and 2016, a small section of the village on the southeast corner was razed. No significant changes were observed between 2016 and 2024.

Area 6. "Suan Dynamite Warehouse"

Approximately 475 meters west of the Suan Mine’s coal loading station is a walled compound with 12 buildings. Activity within the compound suggests that it may be a small threshing facility that also raises small livestock and has a greenhouse. In 2013, the compound was only partially walled and contained six buildings. The wall was completed in 2017, and six of the buildings were renovated in 2019–20. Additional buildings were added by 2023, bringing the total to 12. There have been no further changes between 2023 and 2024.

Fifty meters to the south is a small compound with three bermed buildings that a former detainee identified as the “Suan Dynamite Warehouse.” Additionally, there is another partially bermed building 80 meters to the west of this compound that has also been identified as an explosives storage facility. All of these structures are present in all imagery from 2003 to 2024. The three bermed buildings are similar to structures typically used for explosives storage at mines elsewhere in North Korea, including those within other detention facilities.

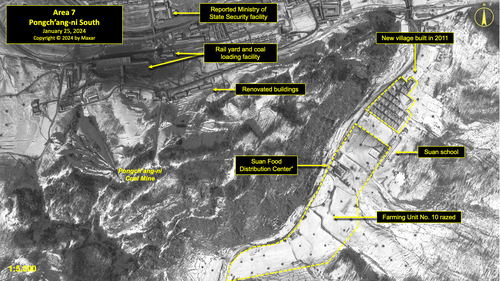

Area 7. Pongch'ang-ni South

Among the more significant activities within this area are the Pongch’ang-ni coal mine, rail coal loading station, sawmill, Ministry of Social Security compound, Suan School, Suan food distribution building, and the former village housing Farming Unit No. 10.Hawk Interview. The name of this village is unknown.[29]

At least 201 houses were razed within this area between 2013 and 2020, including all but four houses in the village associated with what a former detainee identified as Farming Unit No. 10. At the same time, three houses were rebuilt. By November 2020, there were 98 houses within this reporting area. Nearly all of the houses were located within three districts, each with a perimeter wall that was added between 2017 and 2019.

The village associated with Farming Unit No. 10 is present in satellite imagery from at least 2007 to 2015, when razing activity can be first observed. The entire village was razed by 2020, with the exception of what a former detainee identified as the Suan Food Distribution Facility and Suan School. The former has undergone minor renovations over the past eight years. The Suan School building remains, but its current use is unknown.

The Pongch’ang-ni Mine continues to be active. The number of rail cars observed at the coal loading station in the past several years appears to have decreased somewhat, indicating a lower level of activity than before.This development requires further study.[30] Despite the camp’s reported closure, almost all the significant structures at the mine and coal loading station have been renovated to some degree. Eight buildings were constructed between 2013 and 2020, while only one was razed. Coal extracted from the Pongch’ang-ni Mine is moved to the coal storage yard adjacent to the coal loading station. From here, it is loaded onto rail ore cars for transportation to industries around the country.See also Blood Coal Export from North Korea, 62–72.[31]

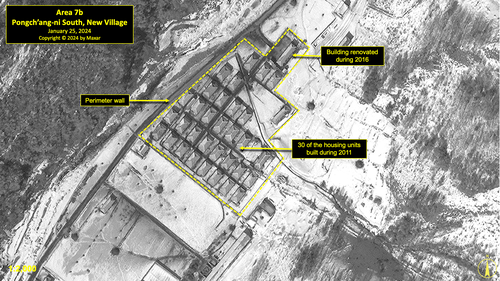

Area 7b. Pongch'ang-ni South, New Village

Immediately north of the Suan School is a small unnamed village built during 2011. This village consists of about 34 housing and administration/support structures, including three that were already present on the site. Between 2017 and 2019, a perimeter wall was built around the village, enclosing an area of 1.8 hectares. One of the administration/support structures was rebuilt sometime between 2013 and 2016. Between 2019 and 2020, one of the older housing units was razed and replaced by another house. No other significant changes were identified from 2020 and 2024.

Area 8. Pongch'ang-ni and Samp'o-dong

This area is known as the Pongch’ang District and encompasses the towns of Pongch’ang-ni and Samp’o-dong. Samp’o-dong, sometimes identified as the “New Village,” is primarily a housing area for camp security and administrative personnel and their dependents. Pongch’ang-ni is the administrative and industrial center for all activity within Kwan-li-so No. 18. It also provides some housing for detainees.

According to a former detainee, among the more significant light industries located in this area are a cement factory, roof tile factory, foodstuffs factory, mine tools factory, and a wood products factory. In addition to the numerous agricultural fields around the two towns, there were reported to be pig farms and processing facilities (slaughterhouses).Hawk Interview. While former detainees state that there were both a cement factory and a roof tile factory, they are both part of the same facility. In addition, the “cement factory” does not appear to be similar other known cement factories in North Korea. It is likely the “cement factory” was simply the name given to that part of the compound where sand, cement, and other ingredients were mixed for production of roof tiles. Between 2003 and 2016, the original chicken farm was converted to a pig farm and expanded.[32] The primary pig farm was razed sometime between 2013 and 2016, but a new livestock facility was built during that time period as a replacement. The slaughterhouses remained as of January 25, 2024.

Activity at the cement and roof tile factories, both located together along the south bank of the Taedong-gang, has been continuously observed in all available imagery. The quarry where raw materials are mined for production is located 350 meters to the east of the factories. It was noticeably enlarged between 2016 and 2020. A plume can be observed emerging from a stack at the tile factory in numerous satellite images since March 30, 2016, including the January 25, 2024 image.

An unidentified light industrial facility is located west of the cement and roof tile factories, next to the rail bridge entering the camp. This facility is visible in all available imagery. It underwent a number of changes over the years, most recently during 2022–2023. As of January 25, 2024, it consisted of approximately 16 buildings.

The Pongch’ang-ni rail station is located on the main rail line for the camp, between the unidentified light industrial facility and the cement and roof tile factories. This station and a support building have been visible in all available imagery since 2007. Both have undergone numerous changes over the years.

Located within the administrative area of Pongch’ang are a number of facilities identified by a former detainee, including the camp headquarters, Ministry of Social Security headquarters, Ministry of State Security headquarters, Cultural Hall (i.e., Kim Family Research Center), Cultural Center, Pongch’ang Clinic, motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility, the Department of Youth Services, a kindergarten and grade school, Pongch’ang Store, several additional stores, and the Pongch’ang Food Distribution Center. Minor changes have been observed at a number of these locations since 2007, most recently in 2019 and 2020.

In terms of housing, there are three large housing sections within Pongch’ang and Samp’o-dong. Between 2013 and 2019, about 118 houses were razed and six rebuilt. Approximately 418 houses remained by November 2020. Most of the housing is surrounded by low perimeter walls. There are eight small guard positions, built between 2017 and 2020. These guard positions are scattered around the housing sections. Minor changes have continued until January 25, 2024.

Area 8b. Pongch'ang-ni Administrative Center

Numerous changes have occurred within the Pongch’ang-ni administrative center since 2013.

At the north end of this area are the houses of the Chief Secretary and Camp Commander. A compound located to the west of the Chief Secretary’s house, consisting of services facilities (including shoe repair and clothes repair shops), was razed in 2016. This area was renovated during 2017–19, and three buildings were added in 2016–17. During 2020, the Chief Secretary’s house was renovated, and the Camp Commander’s house was expanded.

A short distance to the northeast of the Chief Secretary’s house is the motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility. This facility was updated during 2020–24, with several small buildings razed and four buildings added. Further west—across the stream that bisects Pongch’ang-ni—are the Construction Support Office and Pongch’ang Clinic. Outside the southeast corner of the Construction Support Office is the Pongch’ang Clinic. A small tower was removed from in front of the clinic between 2013 and 2016.

To the east of the Chief Secretary and Camp Commander houses are the Samp’o-dong kindergarten and village store. The two-story kindergarten consists of a central building approximately 50 meters in length that is flanked by a hall at each end.

South of these facilities is a larger area consisting of several buildings identified by former detainees as the Kwan-li-so No. 18 administrative headquarters, Samp’o-dong administrative headquarters, central plaza, Department of Youth Services, Pongch’ang School, Kim Family Research Center, and the Cultural Center.

The Kwan-li-so No. 18 administrative headquarters was enlarged between 2013 and 2016 with the addition of a new building. During the same timeframe, two additional small buildings were constructed. Adjacent to the east side of the headquarters is a large public area consisting of four large ponds, a 3,800 m2 paved plaza, and a pavilion. The plaza once had a mural portrait of Kim Il-sung. Between 2011 and 2013, a second mural of Kim Jong-il was added, mirroring a nationwide program of mural installation following Kim Jong-il’s death in 2011.Jacob Bogle, “Kim Jong-un’s First Decade - A Decade of Monument Growth,” Access DPRK, September 29, 2021. https://mynorthkorea.blogspot.com/2021/09/kim-jong-uns-first-decade-decade-of.html.[33]

During 2017–19, a small building was added in the southeast corner. During 2020–23, a second, larger building was added in the center. Immediately to the east is a building reported to be the complex containing the Department of Youth Services. Northeast of this is the Samp’o-dong (sometimes identified as the “New Village”) administrative office. A new building was constructed next to it during 2017–19. Immediately to the south of the Department of Youth Services is the Pongch’ang School, which serves the children (aged 7 to 17) of camp personnel. There was once a tall tower at the southwest corner of the four-way intersection between the school and main administration building. This monument was removed between 2013 and 2016, with only the base remaining.

According to former detainee testimony, the Cultural Center is located approximately 200 meters south of the Kwan-li-so No. 18 administrative headquarters. Meetings were reportedly held at this building each time detainees were released. The building was renovated in 2017. Approximately 50 meters south of the Pongch’ang School is the Kim Family Research Center. This three-story building remains in good repair, and two small buildings were added within the walled compound between 2013 and 2016.

Area 9. Kumpyong-ni, P'yong-dong, and Yŏngdŭng

Located on the northwest side of Pongch’ang-ni, along the Taedong River, are the small villages of Kumpyong-ni and P’yong-dong. P’yong-dong is reported to house Farming Unit No. 1, and Kumpyong-ni houses Farming Unit No. 3. Farming Unit No. 2 is located further south.Hawk Interview.[34] Former detainees have referred to this area as Yŏngdŭng, likely in reference to the Yŏngdŭng mine and its associated town, located further to the south.

Farming Unit No. 1 is located in the small village of P’yong-dong. A small hospital (or clinic) and a re-education building are reportedly located here.Ibid.[35] The education building, however, was demolished during 2016 and a new building constructed in its place later that year. Between 2016 and 2018, all housing units were gradually razed and replaced by 12 new ones between 2017 and 2020. These new houses are partially enclosed by a perimeter wall.

Approximately 600 meters to the west of Farming Unit No. 1 is the Pukch’ang Pig FarmIbid.[36] and a small “distillery village” for those who worked at what was reported to be the camp’s distillery, located a further 1.1 kilometers to the west at Hyonan. In 2013, there were 12 houses in the “distillery village.” By 2016, eight houses had been razed. By November 9, 2020, only one house remained. The information concerning Hyonan and a potential distillery is unclear and conflicting, as the location is also reported to be a guard facility with VIP housing.

As of January 25, 2024, satellite imagery shows a small walled facility with what appear to be guard positions. Some sources indicate that there may be a guard position located in the extreme northwest corner of the Kwan-li-so No. 18, along the Taedong-gang, that is operated by troops from this facility. This remains to be confirmed, however.

Sometime about 2019, a small system of irrigation ditches was excavated in the fields east of P’yong-dong. By 2020, however, these were allowed to fill in and return to cultivated land. Why exactly these ditches were excavated is unclear, as they did not extend into other areas. Regardless, it was another example of moderate improvements to the area’s infrastructure.

In the northeastern corner of this reporting area was the village of Kumpyong-ni, which housed Farming Unit No. 3. In 2013, it consisted of 30 houses and a threshing facility. All of the houses were razed by March 2016, leaving only the threshing building. Subsequently, three buildings were constructed at the threshing facility between 2013 and 2016. In 2017, another building was constructed and two were renovated. Between 2019 and 2020, three buildings were razed, and a new, single building was constructed in their place.

Approximately 1 kilometer south of Kumpyong-ni and 750 meters southeast of P’yong-dong is an area often referred to as Yŏngdŭng. A former detainee stated that Farming Unit No. 2 was located here. In 2013, the area reportedly consisted of a school for detainee children aged 7 to 17, a kindergarten, threshing facility, livestock facility (pig pen), hospital, and a Ministry of State Security office.

The school for 7-to-17-year-olds consisted of three main buildings and a courtyard partially surrounded by a wall. By 2016, one of the buildings had been razed and part of the wall was removed. By August 2018, a second building had been razed, the full length of the wall removed, and the entire courtyard was under cultivation. By November 2020, there were no signs that the remaining building was being used as a school.

The building that has been identified as the Yŏngdŭng Hospital lies 120 meters south of the former school. The original building was razed between 2011 and 2013, and a new building was constructed approximately 15 meters away. Detainee testimony confirms that a small Ministry of State Security office was located within the hospital grounds. After the hospital’s reconstruction, a group of small buildings was added to the front of the hospital’s courtyard. This may be where the Ministry of State Security office is located, or it may have been removed entirely.

Thirty meters south of the new hospital building is a collection of buildings that have variously been reported to have included a kindergarten, a “pig pen” for Farming Unit No. 2, and a threshing facility. From 2004 to 2006, the area remained relatively unchanged. Then, around 2007, a number of buildings were razed and the land was converted to agricultural use. It remained in this state until about 2014–16, when a number of buildings were built, including a threshing facility. Although the level of activity has varied over time, the number and type of buildings present has remained relatively stable since 2016.

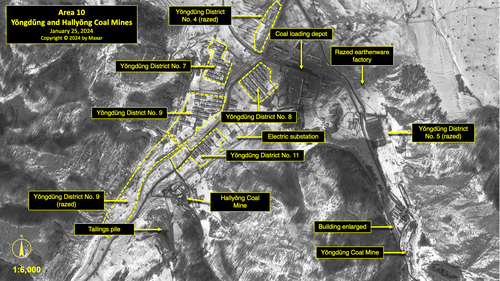

Area 10. Yŏngdŭng, Hallyŏng, and Hanjae Coal Mines

The town of Yŏngdŭng is one of the larger mining areas in Kwan-li-so No. 18. It was reportedly organized into at least eight districts—Districts 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12—that house detainees. Within and around these eight districts are administrative offices, at least two Ministry of State Security buildings, a food distribution center, a carbonate supply building, a small earthenware factory, a mine ore car repair shop, and a workers’ bath site.Ibid.[37] Changes have occurred in the housing districts from 2013 to 2024. To the west of the Hallyŏng mine, Districts 10 and 11 were razed between 2013 and 2015. During 2015–16, 15 buildings within District 4, including the Yŏngdŭng Administrative Office, were razed. The six remaining housing units were enclosed by walls from 2018 to 2019. The earthenware factory, located north of District 9, was razed during 2019–20. District 5 was razed sometime between 2023 and 2024. As of January 25, 2024, all reported detainee housing units (approximately 93 structures) were distributed among the five remaining districts.

Five vertical shaft coal mines are reported to exist—or have existed—in and around Yŏngdŭng, including Hallyŏng, Hanjae, and Yŏngdŭng. A former detainee stated that all of these mines made extensive use of prisoner labor.Ibid.[38] While two of the mines appear to have been abandoned as of 2020, the Hallyŏng, Hanjae, and Yŏngdŭng mines still appeared to be active as of January 25, 2024.

During 2015–16, the Yŏngdŭng coal loading station was rebuilt and enlarged, indicating sustained activity at these mines. Between 2019 and 2020, a new conveyor belt system was constructed at the coal loading station. Between mid-2023 and January 2024, the size and shape of the coal ore piles in the storage yard changed, and the nearby tailings piles increased and changed in shape. This indicates continuing activity at the mine.

At the Hallyŏng mine, located 900 meters southwest of the Yŏngdŭng coal loading station, the only activity of note from 2004 to 2012 was the presence of six or seven buildings of various sizes in the administrative/support area. Sometime between 2013 and 2015, 87 buildings (including one for the Ministry of State Security) in District 11 were razed. This marked the beginning of a number of changes that expanded the mine. By the end of 2015, the mine was upgraded with the addition of a new mine railroad for transporting ore to the Yŏngdŭng coal loading station, and the number of buildings present in the administrative/support area increased to about 12. By the end of 2016, a second large building was added in the administrative/support area, along with several small agricultural buildings including a greenhouse. During 2018–19, a new structure was built to facilitate the handling of increased tailings. During 2023–24, the number of buildings in the administrative/support area increased to approximately 20.

Although there have been minor changes at the Yŏngdŭng mine, typical of what has been observed at other small mines in North Korea, it has remained largely unchanged since 2006. Notably, the tailings piles have not changed significantly since 2006. Two buildings south of the Yŏngdŭng mine were razed in 2015. These buildings were replaced by two buildings in 2016. Two additional buildings closer to the mine were razed in 2016. At the mine, one building was enlarged in 2015–16, and two buildings were renovated in 2016. One of the renovated buildings was reported to be for the Ministry of State Security. Sometime between 2023 and 2024, District 5, which supported the mine, was razed. If the Yŏngdŭng mine remains active, it is likely to be operational at a very low level.

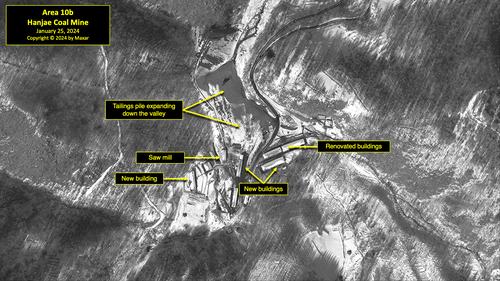

The Hanjae Coal Mine is located approximately 1.2 kilometers southwest of the Hallyŏng mine and 2 kilometers southwest of the Yŏngdŭng coal loading station. From 2003 to about 2008, it consisted of 10 buildings and the mineshaft. However, by 2011, five of the buildings were razed. During this period, only minor changes were observed on the tailings pile. Significant changes began around 2016, by which time the number of buildings had increased to about 16, including a greenhouse. The tailings pile also began to expand. Four years later, the number of buildings increased to 18, including a greenhouse and sawmill, while the tailings pile slowly grew down the valley. As of January 25, 2024, the number of buildings present was approximately 22, and the tailings pile has continued to slowly expand.

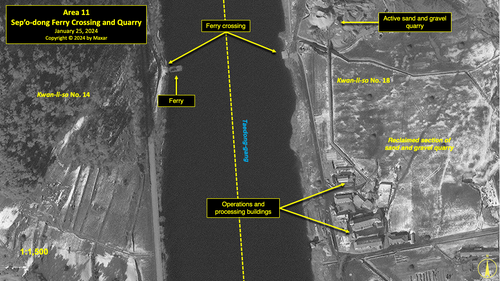

Area 11. Sep'o-dong Ferry Crossing and Quarry

Sometime before 2007, a small sand and gravel quarry was established on the east side of the Taedong-gang, on the north-northwest side of Kwan-li-so No. 18 near the village of Sep’o-dong. Subsequently, between 2007 and 2011, the village of Sep’o-dong was razed and a ferry crossing was constructed. Much of this was done to support construction activity within Kwan-li-so No. 14 on the opposite side of the river.

According to former detainees, some of the buildings razed at Sep’o-dong included a “labor training center” and a facility for the terminally ill, while the cultivated fields had been worked by Farming Unit No. 12.Hawk, HG1, 109; HG2, 210; and Hawk Interview.[39] The ferry crossing, with landings on both sides of the Taedong-gang, includes a 12-meter-long ferry that has been observed transporting vehicles and people.

When first established, the quarry consisted of approximately five administration and processing buildings and a guard position along the river, located some 200 meters south of what would subsequently become the ferry crossing. Over the years, the active pit has slowly moved northward as material was extracted. As it moved north, the former area was returned to agricultural production.

As of January 25, 2024, the sand and gravel quarry remained active, with an administration and processing area covering 0.7 hectares and a pit covering approximately 1.1 hectares.

Burial Grounds (Areas 12–16)

At present, there are a total of five reported burial grounds within the perimeter of Kwan-li-so No. 18. Four of these sites have been identified by former detainees, and one was identified in satellite imagery.

Considering the extremely harsh living conditions reported by former detainees, along with the length of time the camp has been in operation, there are undoubtedly additional burial sites that have not yet been identified. With a few exceptions, there are considerable challenges with identifying or confirming burial grounds within North Korean detention facilities. These areas are often used as farmland, which is routinely cultivated, or are sometimes located in wooded areas.

Of the identified or reported burial grounds at Camp No. 18, two are of traditional Korean style, with individual grave sites that each have a roughly circular appearance and a central burial mound. There is a reasonable likelihood that these were not for detainees, but rather for the camp’s officers and staff or their dependents. Former detainees from other North Korean detention facilities have reported that detainees’ bodies are buried in shallow pits or burned, leaving little to no trace.

A small number of former detainees from other detention facilities have also reported the use of crematories. However, none have been mentioned in interviews with former detainees of Kwan-li-so No. 18, and none have been identified in satellite imagery.

Area 12. Sang-ni "Orchard" Village Burial Ground

A former detainee has identified a burial ground as being located on the north facing slope of a hill immediately north of the Sang-ni Orchard Village.Hawk Interview.[40] Except for typical agricultural activity, this area has remained unchanged in satellite imagery since at least 2007. Satellite imagery has not detected any indications of burial sites.

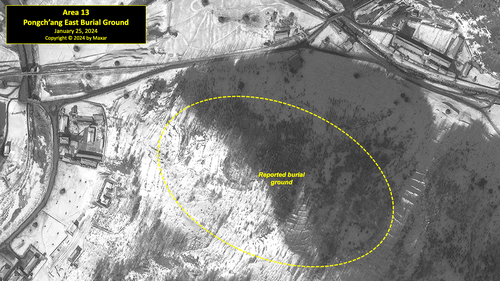

Area 13. Pongch'ang East Burial Ground

This burial ground is located on the east side of Pongch’ang and is the second such site identified by a former detaineeIbid.[41]is on the northern slope of a small, wooded hill east of the village. As with the Sang-ni location, except for typical agricultural activity, this area has remained unchanged in satellite imagery since at least 2007. Satellite imagery has not detected any indications of burial sites.

Area 14. Pongch'ang West Burial Ground

A former detainee identified a third burial ground approximately 650 meters west of the Pongch’ang-ni coal loading station and immediately east of a small unnamed village, where 23 buildings were razed between 2013 and 2017Ibid.[42]with the previous two locations, except for typical agricultural activity, this area has remained unchanged in satellite imagery since at least 2007. Satellite imagery has not detected any indications of burial sites.

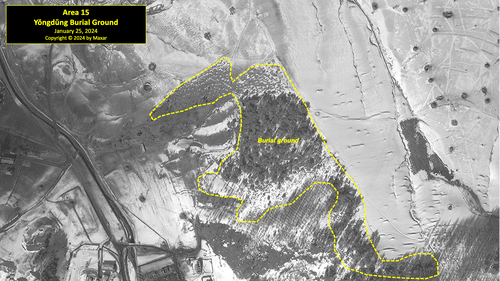

Area 15. Yŏngdŭng Burial Ground

The fourth burial ground, and last identified by a former detainee, is located among several low hills approximately 450 meters east of the Yŏngdŭng coal loading station.Ibid.[43]Immediately to the west of the burial site is Yŏngdŭng District 5, where housing for unmarried detainees is reportedly located. Over 200 traditional burial mounds are visible in this irregularly shaped burial ground that has been visible in all satellite imagery since 2007. No significant changes have been observed to the burial ground since 2013.

Area 16. Samp'o-dong Burial Ground

Located approximately 680 meters southeast of the village of Samp’o-dong and between several cultivated fields is a small, irregularly shaped traditional burial ground. At least 75 individual burial mounds are visible in all satellite imagery since 2007. No significant changes have been observed in satellite imagery over the past five years.

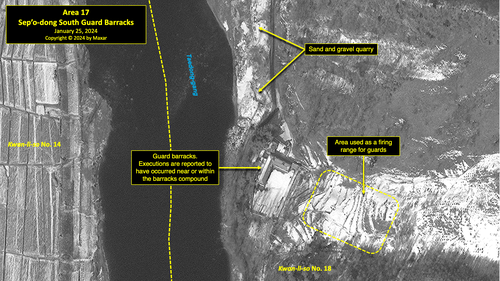

Area 17. Sep'o-dong South Guard Barracks

Located on the east bank of the Taedong-gang and approximately 1 kilometer south of Sep’o-dong, there is a walled guard barracks that is visible in all imagery from 2007 to 2024. Former detainees have indicated that the barracks or the adjacent bank has been used as an execution site in the past.Ibid.[44] The hillside to the east of the barracks is reported to be used as an informal firing range for guards.

In 2007, the barracks consisted of a square walled compound (approximately 40 meters on each side) with a guard tower in its northeast corner and two buildings outside the walls. Sometime between 2008 and 2011, the facility was completely rebuilt into its current form—a 35 meter-by-25-meter L-shaped structure surrounded by a perimeter wall enclosing an area of approximately 0.3 hectares.

The entrance to the barracks is secured by a guard position. A mural or monument can be observed within the courtyard. A second building, roughly square in shape, is located to the north of the main barracks. This second building is separated from the main barracks by a wall, and a small guard position is positioned at the northwest corner of the wall.

Approximately 250 meters north of the barracks and along the Taedong-gang is a small sand quarry that completely lacks the industrial infrastructure seen at the Sep’o-dong Quarry, further to the north. Activity was noted here in satellite imagery from 2007 to 2022. Imagery from 2023 and 2024, however, suggests that this sand quarry may have been abandoned.

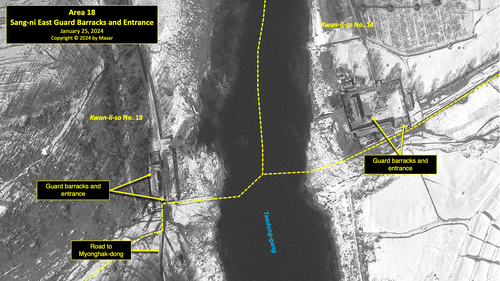

Area 18. Sang-ni East Guard Barracks and Entrance

Located on the west bank of the Taedong-gang, approximately 900 meters east of the Sang-ni Orchard Village, is a small guard barracks and an entrance gate that controls access to Kwan-li-so No. 18 from the civilian coal mining town of Myonghak-dong to the south along a dirt and gravel road. This barracks is also opposite a similar but larger guard barracks and entrance for Kwan-li-so No. 14 on the east side of the Taedong-gang. Between 2013 and 2016, the Sang-ni East guard facility was rebuilt and enlarged. Concurrently, a small unnamed village of 14 houses immediately west of the barracks was razed.

Similar in design to the Sep’o-dong South guard barracks, the walled compound covers approximately 0.31 hectares and contains a central L-shaped building. The entrance to the barracks is secured by a guard position, and there is a mural or monument within the interior courtyard. Approximately 60 meters of fencing was also built in the narrow margin between the river and the guard position, further securing the site.

Located approximately 100 meters south of the barracks are the remains of what appears to have been a reinforced ford across the Taedong-gang. It appears to have been built and actively maintained from 2007 to 2011 before falling into disuse. A further 700 meters south of the guard barracks, and not part of Kwan-li-so No. 18, is a checkpoint with a small guardhouse, built between 2013 and 2016, on the outskirts of the mining village of Myonghak-dong.

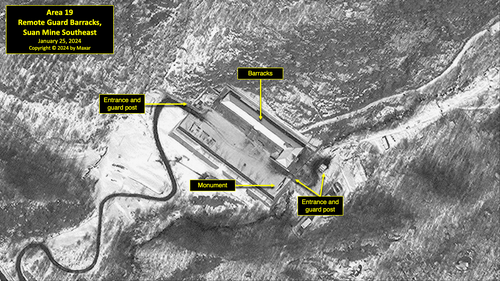

Area 19. Remote Guard Barracks, Suan Mine Southeast

Located in the remote mountainous southeast section of Kwan-li-so No. 18, and 2 kilometers southeast of the Suan mine, there is a new guard barracks facility that was built in 2015.

The main walled compound encompasses approximately 0.52 hectares and consists of a large L-shaped building with a guard position at its entrance in the north wall and a monument. Immediately outside the south wall are two small buildings that appear to be for housing, a small greenhouse, and a second guard position. This facility is similar in size and layout to those observed at Pongch’ang-ni South and Hallyŏng East. This guard barracks and those at Pongch’ang-ni South and Hallyŏng East may also serve as small detention centers.

It is also similar in size and layout to guard barracks observed within other North Korean kwan-li-so. For example, similar structures can be found in the remote north of Kwan-li-so No. 15 at Yodok. A former Yodok detainee identified these buildings as being used for detention and as a guard barracks.Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.[45] While it cannot be ascertained through satellite imagery alone whether Kwan-li-so No. 18’s barracks facilities are also used as detention centers, the remote location and physical similarities with other known facilities in North Korea should be noted. The construction of these barracks directly contradicts reports of Kwan-li-so No. 18’s closure.

As of January 25, 2024, this guard barracks remained active, as indicated by vehicle tracks in the snow.

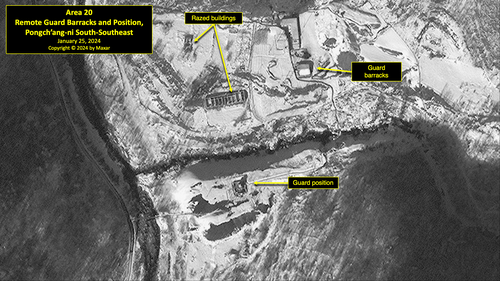

Area 20. Remote Guard Barracks and Position, Pongch'ang-ni South-Southeast

Located along the southern perimeter of the camp, approximately 3 kilometers south of Pongch’ang-ni, there is a remote guard position built during 2015–16. It is positioned on the site of a former mine. All but two of the mine’s buildings were demolished sometime between 2013 and 2015. In 2016, a small guard position was constructed on top of the tailings pile and the two remaining buildings were converted to a small guard barracks. The position was then rebuilt in 2017 and appears to secure the only road south, which leads to the Pongch’ang-ni South guard barracks. As of January 25, 2024, this guard position remained active, as indicated by tracks in the snow.

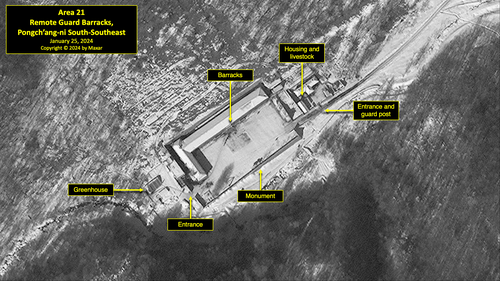

Area 21. Remote Guard Barracks, Pongch'ang-ni South

Located in the remote mountainous area approximately 4.1 kilometers south of Pongch’ang-ni and 1,400 meters southwest of the Pongch’ang-ni South-Southeast guard position, there is a walled guard barracks that was built in 2015. This walled compound partially encloses approximately 0.7 hectares, consisting of three distinct walled sections. The main section consists of a large L-shaped building, monument, and a courtyard with areas outlined for sports and exercise/physical training. The two smaller walled sections appear to contain headquarters, housing, and agricultural or livestock areas. A small checkpoint may be located along the entrance wall. A gate on the west side leads to two or three support buildings, one of which is a greenhouse. This gate also leads to a small, long-abandoned mine 400-meters to the southwest. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by tracks in the snow.

Area 22. Remote Guard Barracks, Hallyŏng East

Located in the southwestern section of Kwan-li-so No. 18, and approximately 1,200 meters south of the Hallyŏng Coal Mine, there is a third walled guard barracks that was built in 2015. This walled compound encloses approximately 0.33 hectares. It consists of an L-shaped building, a guard position on the southwest corner, a monument, an entrance on its east side, and a smaller walled compound attached to its northeast corner. This second compound encloses approximately 530m2 and contains a single building. A winding mountain road leads downhill from this compound to the guard position and camp entrance connecting to the town of Hallyŏng-ni. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by the partial clearing of snow.

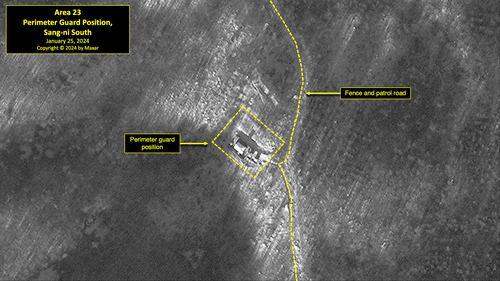

Area 23. Perimeter Guard Position, Sang-ni South

This small guard position is located on the camp’s eastern perimeter, approximately 1.8 kilometers southwest of the Sang-ni East Guard Barracks and entrance gate. It is typical of checkpoints located elsewhere along Kwan-li-so No. 18’s perimeter and of those identified along the remote security perimeters of other kwan-li-so.

This guard position was built sometime between 2013 and 2016. It consists of a small rectangular building surrounded by two walls encompassing approximately 0.08 hectares. This guard position is approximately 15 meters from the perimeter fence and a patrol path. The patrol path runs northeast and southwest to the next guard positions. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by the partial clearing of snow.

Area 24. Perimeter Guard Position, Suan Mine Southeast

This guard position is located 1,500 meters east of the perimeter guard barracks, southeast of the Suan Mine. This guard position was built sometime between 2013 and 2015. It consists of two small buildings surrounded by double walls. The outer wall encompasses approximately 0.19 hectares. This guard position is approximately 230-meters from the perimeter fence and patrol path and a second path leads west to the guard barracks, southeast of the Suan Mine. The patrol path runs both north and south to the next guard positions. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by the partial clearing of snow.

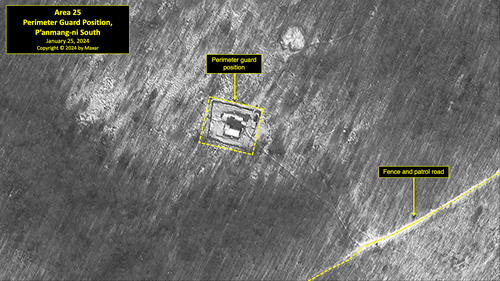

Area 25. Perimeter Guard Position, P'anmang-ni South

Located approximately 4.2 kilometers southeast of the Pongch’ang-ni South Guard Barracks is the P’anmang-ni South perimeter guard position. This position was originally built between 2013 and 2015. It was razed in 2016 and rebuilt 80 meters away at its present position. It is surrounded by double walls that encompass approximately 0.11 hectares and contain two buildings. This guard position is connected to the patrol path approximately 120 meters away that runs both northeast and southwest to the next guard positions. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by the partial clearing of snow.

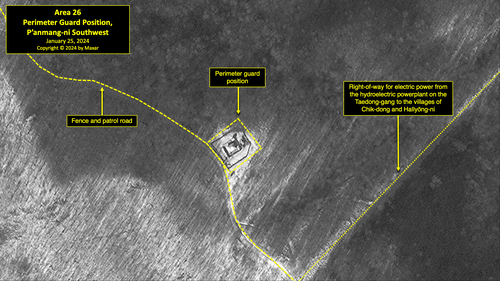

Area 26. Perimeter Guard Position, P'anmang-ni Southwest

Located 3.7 kilometers southwest of the P’anmang-ni Southwest Guard Barracks is the P’anmang-ni Southwest perimeter guard position. It was built between 2013 and 2015, replacing an older, abandoned position 350 meters to the northeast. The new position is surrounded by double walls that encompass approximately 0.06 hectares and contain one large and two small buildings. This guard position is immediately adjacent to a patrol path that runs both northwest and southeast to the next guard positions. Trails connect this guard position to the P’anmang-ni Southwest Guard Barracks. An electric right-of-way passes to the east of the guard position to provide power from the hydroelectric power plant on the Taedong-gang to the villages of Chik-dong and Hallyŏng-ni. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by the partial clearing of snow.

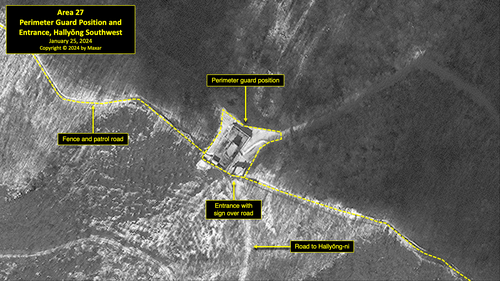

Area 27. Perimeter Guard Position and Entrance, Hallyŏng Southwest

Located 1 kilometer southwest of the Hanjae mine is the Hallyŏng Southwest perimeter guard position and entrance. A perimeter guard position appears to have been present at this location since Kwan-li-so No. 18’s establishment. The earliest available satellite imagery shows that this position was razed and replaced by a semi-enclosed guard position that is shown in imagery from 2004. Subsequently, during 2015–16, this position was razed and replaced by a single-walled compound consisting of three buildings, enclosing an area of approximately 0.06 hectares. As of January 25, 2024, it consisted of two buildings and a sign board over the dirt road leading southwest to the coal mining town of Hallyŏng-ni, 1 kilometer to the southwest. This dirt road is useable by light vehicles and foot traffic. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by the partial clearing of snow.

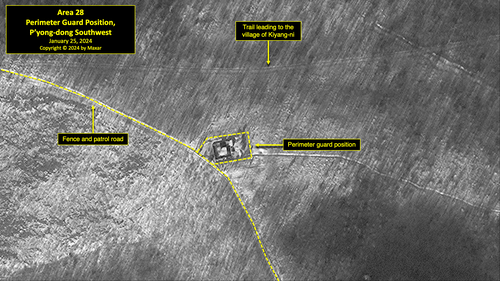

Area 28. Perimeter Guard Position, P'yong-dong Southwest

Located on the western perimeter, 2.6 kilometers southwest of P’yong-dong, there is another double-walled guard position. This position was constructed in 2015, replacing an older guard position located 280 meters to the northeast that was razed sometime after December 13, 2014. An old trail leading to the village of Kiyang-ni passes 65 meters north of the position. Like the other guard positions noted above, this position consists of a central building surrounded by a wall and an outer fence. The northwest corner of the guard building has what appears to be a raised observation platform. As of January 25, 2024, this barracks compound remained active, as indicated by the partial clearing of snow.

Assessment

Observations and analysis derived from satellite imagery collected by Maxar, combined with statements by former detainees and other publicly available information, indicate the following.

- Although North Korea officially announced the closure of Kwan-li-so No. 18 in 2006, satellite imagery indicates that the camp has not been completely razed. It further indicates that the remaining facility, whether officially designated as such or not, is a large and active detention facility.

- Despite the 2006 closure announcement, substantial infrastructure closure activity was only identified in satellite imagery six years later. This closure activity began in approximately 2012 and lasted until 2016. Moreover, it occurred alongside significant ongoing operations and development activity.

- Approximately 830 structures in 50 locations were razed between 2012 and January 2024. Concurrently, this was accompanied by the construction of approximately 225 new structures in 51 locations, and the renovation of approximately 90 existing structures in 24 locations.

- Despite satellite imagery coverage of the prison, HRNK is presently unable to estimate either the number of detainees remaining within the deactivated sections of the camp, those held within the active elements of the camp, or precisely delineate the areas occupied by the remaining detainee population.

- Since 2012, satellite imagery has shown the construction of five new perimeter guard positions, one significant internal guard position, and three new guard barracks/detention facilities. Satellite imagery also identified an estimated 35–40 small guard posts (scattered around the camp, along the Taedong-gang, and internally throughout the camp), and the enclosure of a number of reorganized residential areas with walls.

- The Kwan-li-so No. 18 area remains active and is well-maintained, as indicated by numerous agricultural, light industrial, and mining activities.

- The agricultural, mining, light industrial, housing, and support structures throughout the area appear to be well-maintained and in relatively good repair.

- Although the road network supporting the area has remained essentially unchanged, it is generally well-maintained, and some sections have been improved.

- The small number of livestock facilities within the camp are well-maintained and active.

- Orchards and fields under cultivation are well-maintained and show no signs of being left fallow.

Broad Conclusion

It is clear that the prisoner population of Kwan-li-so No. 18 has been reduced. However, satellite imagery shows that the North Korean regime is continuing to use areas of the camp to house detainees and to exploit them for various forms of economic activity. The recent changes made to mining, light industrial, and agricultural areas of the camp suggest that human rights abuses and forced labor have continued, and that additional detention facilities may continue to be established in other remote areas of the camp.

Acknowledgements

HRNK would like to extend a special note of thanks to satellite imagery analyst Jacob Bogle for his work on an earlier version of this report, and also to Bobby Holt for his gracious support of HRNK’s efforts to analyze and document conditions in Kwan-li-so No. 18.

HRNK is always grateful to veteran imagery analyst Al Anderson for his staunch and unwavering friendship, wise counsel, and support.

HRNK would also like to express sincere gratitude to the following individuals for their contributions: Amanda Mortwedt Oh, for drafting and reviewing this report; Maria Del Carmen Corte and Joseph Han Sung Lim for their editorial work and design of the report; Ava Jane Moorlach for her graphic design assistance; and Guk-hyeon An, Scott Cho, Lauren Chung, Michelle Dang, Diletta De Luca, Yubin Jun, Doohyun Kim, Claire McCrea, Jung-eun Park, Juntae Rocker, David Shaw, and Lia Vincenzo for their research and imagery analysis support.

References

- Previous reports in the project can be found at: https://www.hrnk.org/publications/hrnk-publications.php.

- For additional information concerning Kwan-li-so No. 18 from 2003 through 2013, please see HRNK’s Hidden Gulag series of reports by David Hawk: The Hidden Gulag: Exposing North Korea’s Prison Camps (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2003). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/The_Hidden_Gulag.pdf (hereafter: HG1); The Hidden Gulag: The Lives and Voices of “Those Who are Sent to the Mountains” (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2012). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_HiddenGulag2_Web_5-18.pdf (hereafter: HG2); North Korea’s Hidden Gulag: Interpreting Reports of Changes in the Prison Camps (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2013). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/NKHiddenGulag_DavidHawk(2).pdf (hereafter: HG3).

- Hawk, HG1, 24–25, 36–38, 101–08; Parliament of Canada, Subcommittee on International Human Rights of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, Number 40, 3rd Session, 40th Parliament, Testimony of Kim Hye-sook, February 1, 2011. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/403/SDIR/Evidence/EV4916717/SDIREV40-E.PDF; Hawk, HG2, 27, 48, 70–77, 216–21; Hawk, HG3, 23–33; Han Dong-ho et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2014 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, July 2014), 139–43; Do Kyung-ok et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2015 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, September 2015), 80–84; Do Kyung-ok et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2016 (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, April 2016), 79–81; UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, UN Doc. A/HRC/25/CRP.1, February 7, 2014, 65–66, 199; 2015 White Paper on North Korean Human Rights (Seoul: Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, December 2015), 426.

- Ibid.

- Lee Keum-soon et al., Bukhan jeongchibeom suyongso [North Korea’s Political Prison Camps] (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification, 2013), 17. https://repo.kinu.or.kr/bitstream/2015.oak/2246/1/0001459195.pdf.

- Written testimony obtained by HRNK. The 1997 Sim-hwa-jo incident, also known as the Sim-hwa-jo Sa-eop (Intensification Operation), was a massive purge of many of Kim Il-sung’s close associates, their institutional support structure, and family members. The goal of this purge was twofold: to replace the old power base with Kim Jong-il loyalists, and to identify and blame scapegoats for the catastrophic policy failure that resulted in the great famine and humanitarian disaster of the 1990s. Eventually, the Public Security Department (later known as the Ministry of People’s Security, currently known as the Ministry of Social Security) incarcerated or executed over 30,000 officials and family members. See Ken E. Gause, Coercion, Control, Surveillance, and Punishment: An Examination of the North Korean Police State, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2013), 59, 131–35. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_Ken-Gause_Translation_5_29_13.pdf.

- Mun Dong-Hui, “Kim Jong Un reopens political prison camp to house political enemies,” Daily NK, January 9, 2024. https://www.dailynk.com/english/kim-jong-un-reopens-political-prison-camp-house-political-enemies/.

- Hawk, HG1, 24–25, 36–38, 101–08; HG2, 27, 48, 70-77, 216–21; and HG3, 23-33.