Overview

Social sustainability revolves around how the zone treats its workers and the surrounding community. We observed variation in the provision of housing, training facilities and quality of infrastructure supporting workers' commutes.

Imagery can provide insight into the level of support a zone provides for its workers, but often leaves unanswered questions. Contextual research about how these facilities are being used is important to providing a balanced assessment.

Activity

The focus of our imagery analysis is on cataloging facilities that would be used towards bettering the life of the resident workers. Housing, training facilities and even paved access roads to the entrance of the zone for commuting are all included.

How are we evaluating?

Social sustainability presents unique challenges when using an approach based on satellite imagery. While all our indicators rely on physical proxies, social sustainability is also heavily influenced by the behavior of zone operators and workers. Because of this, our indicators in the categories of health, education, quality of life, and labor relations necessarily include a blend of imagery and contextual research.

Indicators

Health: Chinese overseas SEZs exist in developing countries where medical infrastructure widely varies in availability and quality. This is difficult to ascertain via imagery alone. At minimum, a hospital or clinic within close proximity of a zone increases the chance of timely care for zone staff in a medical emergency.1 We evaluate the distance of a zone to medical facilities as proxy for healthcare capacity, supplementing imagery with open-source research on quality of care, availability, and cost where reports are available.

Education: For host countries, SEZs may offer the potential to develop a more skilled labor force able to participate in higher value-added activities. Beyond standard job training, additional vocational training can occur inside a tenant company or in a dedicated training facility. We examine zones for the presence of identifiable training facilities (including those constructed by zone management). Where applicable and where open-source reports are available, we also consider the presence of local universities and vocational schools that have a formal relationship with a given zone. We acknowledge physical installations like classrooms may not illustrate the full extent of training, which may conducted inside other SEZ or resident firm buildings. Additionally, the amount and quality of vocational training also vary dramatically by industry and firm.2 We supplement our analysis with survey data for specific zones, where available.

Quality of Life: This indicator preliminarily examines transit and housing for zone workers. We evaluate the quality of infrastructure leading to the zone, and whether or not the zone provides worker housing. Infrastructure can include well-paved roads that provide easy access, and/or sponsored transit for commuters. We do not directly address commute times due to a lack of systemic data for all zones, and are not able to draw direct conclusions on housing quality or overcrowding. We supplement with open-source reports and media interviews.

Labor Relations: We draw on open-source reporting, rather than imagery, to qualitatively evaluate workforce issues for our selected zones; for example, firms within each zone may compensate workers poorly. For this indicator, we do not draw directly on satellite imagery.

What did we see in the imagery?

Health: Access to healthcare and service quality widely vary in China-funded SEZs. The mining operation in Chambishi, Zambia, saw an explosion in 2005 which killed dozens of miners.3 At the Chambishi copper smelter, which started operations years after that incident, in 2008, we see some evidence of the welfare of workers being accounted for.The smelter complex appears to have a first-aid clinic on site, with an ambulance also visible in this ground-level photograph. However, for an industry with an abundance of heavy machinery and with multiple mines operating, the question remains of whether the size of the clinic is adequate.

Additionally, the parent company of the SEZ at Chambishi, China's Nonferrous Metals Company (CNMC) has also done something unique among the zones we surveyed: it has opened its own hospital. Located in the nearby town of Kitwe in Zambia's Copperbelt, the Sinozam Friendship Hospital is owned and operated by CNMC, and services are free to all CNMC employees.4 This was the only instance we found of a Chinese overseas SEZ operating its own hospital facilities. While positive for Chambishi's score, this may simply reflect standard practice for Zambia's mining industry; compared to facilities run by non-Chinese multinational firms, some sources suggest Chinese facilities may offer comparatively less care than competing mines.5 More recently in 2018, reports emerged that the Sinozam hospital had been shut down for apparent violations of Zambian law, raising doubts about its own management.6

The only other zone that we found a hospital within the zone boundary was at Lekki FTZ in Nigeria. Zone management appears to have contracted with a local hospital chain to open a small branch location.

The results of the rest of our survey showed a lack of strong evidence for on-site dedicated medical facilities. Many zones had local hospitals within a few miles of the zone, but with ambulance service and quality of care uncertain.

Education: The prospect of skill transfer and workforce training makes SEZs attractive to host countries.7 Countries like, Cambodia, have direct requirements for zone developers to include vocational training for local workers. However, satellite imagery of our surveyed zones shows few buildings that can be conclusively identified as training facilities.

The smaller training facility in Sihanoukville SEZ was built in 2012 with the help of Wuxi, a Chinese state-run vocational school. The larger facility is the Preah Sihanouk Cambodia-China Friendship Polytechnic Institute. While not pictured, the zone has also partnered with Wuxi to build the Sihanoukville Institute of Business and Technology, where reports promise on-site language and vocational instruction.8 This appears to be the largest instance of zone-backed vocational facilities in our 10 Chinese zones, possibly driven by Sihanoukville's large size and need for skilled workers.

Other zones rely more on educational partnerships with external institutions. KITIC near Jakarta is part of a larger industrial zone called GIIC, which directly advertises its partnership with a local vocational school and university and recruits directly.9

Besides vocational education, some zones have pledged to support local non-vocational education. In Zambia, zone operator CNMC lists supporting education as a goal in their report on sustainability, and they have donated materials to help construct a classroom block at Chambishi secondary school.

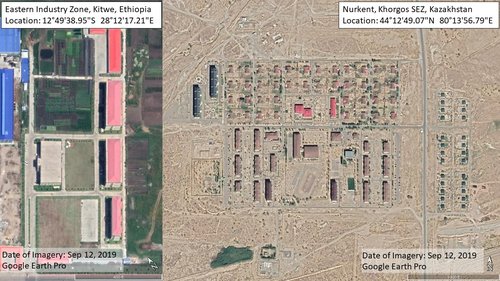

Quality of Life: A more contentious aspect of SEZ infrastructure is the provision of worker housing. Proponents for worker housing will argue that since zones often located in distant rural areas where land is plentiful, on-site housing can limit commute time and improve the standard of living.10 Where housing is provided by zones in our subset, it often exists on-site, and sometimes next to restaurants or parks. The most ambitious project is at Khorgos, where a small city has been constructed named Nurkent. Here, free housing is provided to workers supporting both the nearby economic zone and border crossing with China. In the accompanying structured geo-located files, we annotate these possible sites with the label "kmlGlobal SEZ Facility Annotationsworker housing or dormitory."

Satellite imagery can only illuminate so much: whether or not the buildings interiors are up to code, overcrowded, or used for imported (rather than local) labor is difficult to distinguish from imagery alone. The risk for illicit or illegal activities to be overlooked in worker housing is also a cause for concern.11 Broadly, housing must be accompanied by strong management and policy to ensure workers and investors can benefit.

For worker commutes, we can roughly assess road quality to and from the zones, giving us an idea of how well existing local infrastructure can handle SEZ development.

Among our subset, we rate KITIC highly: it has multi-lane highway leading to the zone, and a highly developed interior set of roads. Others, such as Ogun, have poor or unpaved roads, working their way through local towns and villages before arriving at the nearest major thoroughfare.

While this may seem to be a problem for host countries to solve, zones often have a powerful ability to influence their communities in less developed locations. CNMC donated road rehabilitation equipment to a local municipal council and provided funds for a bus shelter and a car park in Kitwe, a large neighbor city to Chambishi.

Conclusion

Social sustainability cannot be ignored: zones that are better able to support workers are likely to benefit from improved performance and productivity. Across our case subset, zones displayed substantial variation. One area for future exploration is the issue of population displacement for zone development. Locals were displaced during the construction of Ethiopia's Eastern Industry Zone, and years later, local reporting still suggests there is tension between relocated residents and zone developers.12

Our preliminary indicators suggest that satellite imagery can offer some insight into social conditions at China-built SEZs, but require substantial context from other open source data and reporting. What zones do with infrastructure matters as much as what they build.

For part 3 of this series, we will examine in-depth one influential overseas Chinese SEZ: the China-Zambia Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone.

References

- The Effect of Distance on the Use of Emergency Hospital Services in a Spanish Region With High Population Dispersion: A Multilevel Analysis, 2003, 9.

- Ding Fei, Work, Employment, and Training Through Africa-China Cooperation Zones: Evidence from the Eastern Industrial Zone in Ethiopia, n.d., 2021.

- Mine Blast Leaves 46 Dead in Zambia, accessed April 29, 2020, https://www.iol.co.za/news/africa/mine-blast-leaves-46-dead-in-zambia-239275.

- Matt Wells and Human Rights Watch (Organization), You'll Be Fired If You Refuse: Labor Abuses in Zambias Chinese State-Owned Copper Mines (New York, NY: Human Rights Watch, 2011), 49.

- Wells and Human Rights Watch (Organization), 49.

- Sinozam Hospital Closed, The Independent Observer (blog), October 25, 2018, https://tiozambia.com/sinozam-hospital-closed/.

- World Investment Report 2019 - Special Economic Zones, World Investment Report, 2019, 165.

- Wuxi Helps Build First Chinese University in Cambodia, accessed April 28, 2020, http://english.jsjyt.edu.cn/2018-11/28/c_294536.htm.

- Indonesia Industrial Estates Directory 2018-2019, Greenland International Industrial Center (GIIC), n.d.

- Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation and Ministry of Commerce of the Peoples Republic of China, Report on Fostering Sustainable Development through Chinese Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones along the Belt and Road (United Nations Development Program, April 2019).

- Asian Development Bank, A Health Impact Assessment Framework for Special Economic Zones in the Greater Mekong Subregion, 0 ed. (Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, May 2018), https://doi.org/10.22617/TCS189221-2.

- Expansion of Ethiopias First Industrial Park Reopens Old Wounds - Reuters, accessed April 29, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-landrights-industrial/expansion-of-ethiopias-first-industrial-park-reopens-old-wounds-idUSKBN1FL59R.

Oct 26, 2016

MOFCOM recognition of Pengsheng Industrial Park

Mar 28, 2013

China Launches the Belt and Road Initiative

China's development and investment initiatives to stretch from East Asia to Europe with the goal of building regional interconnectivity and economic integrationJun 01, 2010

MOFCOM recognition of Saysettha Development Zone

Apr 06, 2009

MOFCOM recognition of Sihanoukville SEZ

Nov 01, 2007

MOFCOM recognition of Lekki FTZ

Nov 01, 2007

MOFCOM recognition of TEDA Suez SEZ

Nov 03, 2006

MOFCOM recognition of Ogun-Guangdong SEZ

Nov 03, 2006

MOFCOM recognition of Zambia-China Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone (ZCCZ)

Source: East Asia Forum

Mar 06, 2006

China Launches Overseas Special Economic Zones

Chinese government announces its long-term plan to develop up to fifty overseas economic and trade cooperation zonesMar 15, 2000

China Launches "Going Global" Strategy

In an effort to promote Chinese investments abroad, the government eased administrative hurdles for outward investment

Look Ahead

Social sustainability is important but often subordinated to concerns about economic growth. Promises from zones for improving social sustainability are particularly vulnerable to behavior that either subverts or ignores these commitments. Incorporating imagery to validate the progress being made in an SEZ is invaluable to holding the tenant companies and zone management accountable. As countries globally look to bolster economic growth by investing in SEZs, either with or without Chinese support, we encourage the proactive use of GEOINT to ensure that promises towards workers and communities are kept.

Things to Watch

- Is the scale of worker housing development large enough to meet demand?

- How to evaluate the quality of housing from imagery?

- Looking for indicators of mass transit expansion in imagery to complement the expansion of road and rail infrastructure

About The Authors

Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs, 2020

Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs, 2020

Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs, 2020

Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs, 2020

Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs, 2020

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.