Overview

We assess that China is engaging and financially investing in development projects in Papua New Guinea to establish a stronger commercial presence and to potentially attain dual-use options in the South Pacific to counter Western influence in the region. This report covers two infrastructure projects in Papua New Guinea with Chinese activity: 1) the Momote Airport renovations and 2) the Ihu Special Economic Zone (SEZ) development.

Press reporting, business literature, social media, video data, and open imagery suggest Beijing's interest in widening China's economic footprint and obtaining potential dual-use options for infrastructure projects in Papua New Guinea. Yet, there are no current overhead imagery sources that illustrate Chinese military infrastructure or dual-use activity in Papua New Guinea at this time.

Activity

At Momote Airport, located only a short distance from the Papua New Guinean Lombrum Naval Base, a partially Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) extended the airstrip and installed a new terminal and airport apron. Due to recent defense agreements, the Momote and Lombrum sites are now open to the U.S. and Australian navies. Commercial ties to Momote Airport could potentially allow China to use its access to the facilities to collect intelligence on Western military activity. Although there are no open sources to confirm Chinese intelligence collection at Momote, there are potential concerns with base information passed back to China due to the 2017 Chinese National Intelligence Law, which obligates Chinese entities to provide intelligence to the People's Republic of China (PRC) in service to national security. Chinese "dual-use" at Momote is now unlikely given the recent agreement for the U.S. to use the base, but the history and context of Momote can help better understand more ambiguous Chinese commercial ventures such as the Ihu SEZ. At the Ihu SEZ, Beijing invested a significant amount of funding towards the project, which included general plans for a naval and military base along with several civilian economic sectors. Recent imagery illustrates the SEZ in the early stages of the project with the construction of poorly maintained roads and no clear development of a naval or military base. Aside from the disproportionate amount of Chinese financing of the SEZ, the PRC has not otherwise openly expressed interest in the bases. Furthermore, Papua New Guinean project officials have provided mixed messaging about committing to Chinese access to the future bases.

On July 11, 2022, the Global Times, a Chinese state-owned newspaper, reported that the Chinese Embassy in Papua New Guinea refuted media claims that China's commercial projects in the country are aimed at military purposes. They stated that the media report was "completely baseless and hype with ulterior motives." In November 2022, the Papua New Guinea Prime Minister made a similar claim in a Bloomberg article, stating that “China has never expressed clearly their interest for a military base or presence of that nature in Papua New Guinea.” Despite public denials, we assess that China is actively engaging and financially investing in development projects in Papua New Guinea to establish a stronger commercial presence and to potentially attain dual-use options in the South Pacific to counter Western influence in the region. Although some open-source reporting from groups like the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and United States Institute of Peace as well as indirect evidence, such as highly disproportionate funding at Ihu, suggest Beijing’s potential interest in dual-use options for their projects in the South Pacific, there are no current imagery sources that illustrate Chinese military infrastructure or dual-use activity in place on Papua New Guinea at this time.

We have moderate confidence in our assessment based on commercial and publicly available satellite imagery and open-source reporting, including Papua New Guinea media outlets, Australian and U.S.-based articles, and social media. This piece acknowledges the inherent bias in certain state-run media outlets. The development projects we analyzed include improvements at the Momote Airport and the investment and construction of the Ihu Special Economic Zone (SEZ). Figure 1 illustrates the location of the two projects.

BACKGROUND

In recent years, China has increasingly sought to compete with the U.S. and its regional ally Australia for influence in the South Pacific island nations, specifically in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea is strategically located in the Indo-Pacific, offering a location that, in a conflict, would bolster Australia's maritime security and provide the U.S.-Australian coalition a way to project military power northward toward China and Southeast Asia. For China, the island’s location gives it a potential avenue to control valuable sea lines of communication that lead to Australia’s eastern coast and New Zealand.

In an effort to gain access to Papua New Guinea, China’s outreach strategy has entailed engaging in infrastructure projects in the region. The locations of these projects engender a fear in Western defense circles that China’s seemingly benign civil programs may have a “dual-use” capability. With the signed Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) between the U.S. and Papua New Guinea in May 2023, China’s growing presence on the island may lead to increased tension with the U.S. and allies in the region. On May 19, 2023, in response to a scheduled visit by U.S. Secretary Anthony Blinken to Papua New Guinea, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin shared China’s opposition to the “introduction of any geopolitical games into the Pacific Island…”

Amid rising tensions between China and the U.S., Chinese activity and/or financial investment in two Papua New Guinean projects have received scrutiny due to the projects’ strategic locations and their potential dual-use capacities. The first project, Chinese-led renovations at Momote Airport, sparked concern due to its proximity to the Lombrum Naval Base. Although Lombrum is owned by Papua New Guinea and is purposed for their vessels, the island nation has provided base access to the U.S. and Australian navies. Additionally, the recent DCA permits the U.S. military to use Momote Airport. The second project, the Ihu SEZ, deserves attention for several reasons: 1) the general plans to build a military and naval base, 2) its location near the Torres Strait, north of Australia, and 3) the disproportionate level of Chinese financial investment in the SEZ.

MOMOTE AIRPORT

In late 2016, the Asia Development Bank approved a plan to finance improvements at Papua New Guinea’s Momote Airport. The airport is located on Manus Island, approximately 6 km (3.9 miles) southeast of Lombrum Naval Base (see Figure 2), which is operated by the Papua New Guinea Defence Force (PNGDF). Prompted by the rise of China and its more aggressive posture in the region, the U.S. and Australia endeavored to build and bolster Western influence in Papua New Guinea. In November 2018, former U.S. Vice President Mike Pence signaled support for the Lombrum Joint Initiative with Australia. The initiative supports the redevelopment of the base and builds the PNGDF’s capability to protect its borders and maritime resources through mentoring, training, and infrastructure development at Lombrum. In late 2018, the Chief of the Royal Australian Navy stated that the redevelopment was “hugely important” to deepen ties with Papua New Guinea and added that Australian ships could visit the base for resupplying purposes. The West’s efforts to increase cooperation with Papua New Guinea culminated in the signing of the 2023 DCA, which gave the U.S. military “unimpeded access” to both Momote Airport and Lombrum Naval Base.

In December 2016, China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC), a partial Chinese SOE and a subsidiary of the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), signed an agreement with Papua New Guinea’s National Airports Corporation to provide improvements to the Momote Airport. It is important to note that the U.S. Commerce Department added CCCC to the “Entity List” on August 26, 2020, barring them from doing business with U.S. firms. The CCCC joined the U.S. “Entity List” for their role in helping the Chinese military construct and militarize the internationally condemned artificial islands in the South China Sea.

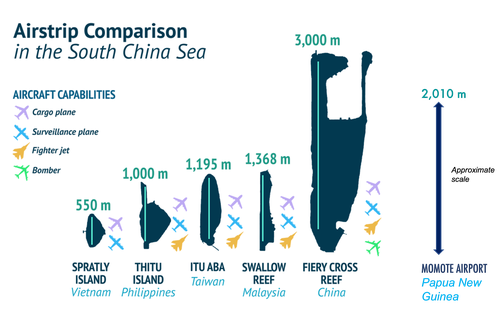

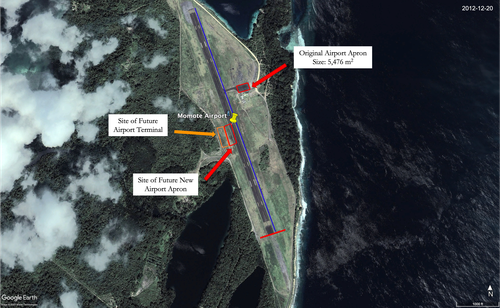

Official renovations at the airport began on September 8, 2017. The most noticeable developments included an extension of the airstrip, increasing the length from 1,810 meters (m) to 2,010 m (see Figures 3 and 4). According to satellite imagery, the CHEC completed the extension between January and March 2018. The length of the new airstrip can accommodate most commercial and military aircraft. Accounting for weather conditions and weight, civilian aircraft such as the Boeing 737-700 and 737-800 and military aircraft such as the Chinese Y-20, a large military transport airplane, can take off and land at the newly renovated Momote Airport. Figure 5 illustrates the length of other airstrips in the Pacific, specifically in the South China Sea, and provides context for the Momote Airport airstrip and its corresponding aircraft capabilities. The Momote airstrip is larger than the airstrip at Malaysia’s Swallow Reef (1,368 m) yet smaller than China’s airstrip on Fiery Cross Reef (3,000 m). Figure 5 uses the South China Sea as context, but it is important to note that there is no evidence of Chinese military activity in Papua New Guinea in the same way as the South China Sea and that Momote is currently only being used for civilian airlines. The figure simply provides additional context.

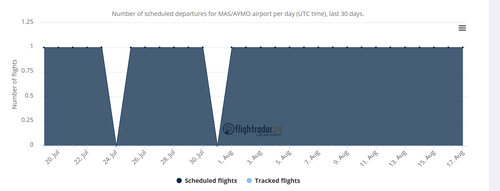

Furthermore, Momote Airport exclusively services Air Niugini, the national airline of Papua New Guinea, with routes to four domestic airports, including the capital, Port Moresby (see Figure 6). Open flight data from July 20 to August 17, 2023 indicate that the airport had low levels of air traffic, operating up to one flight a day, according to data from Flightradar24, an online flight tracking service (see Figure 7).

By April 2021, the CHEC completed the runway extension project and commenced building a new airport terminal. Additional renovations included a new airport apron, almost triple the size of the original apron, and precision landing aids on the runway (see Figures 8 to 10). By April 2022, the improved Momote Airport was completed and officially in operation, according to local Papua New Guinean news media. Figure 11 shows the Momote Airport as of July 2023, with no further developments at the date of publication.

The Momote Airport project, among others like it, provided Beijing an early entry point to become a major economic player in Papua New Guinea. The commencement of the airport renovations coincided with a time when Papua New Guinea was in political courtship with the PRC, which led up to the nation’s official enlistment into the Belt and Road Initiative in June 2018.

Post-DCA, China’s interest in Momote Airport remains unclear. China’s objectives at Momote may have evolved over time with the changing geopolitical situation in the South Pacific. China's initial intentions for the project may have been for a civilian purpose to generate jobs and/or for military purposes. If the latter, the U.S. defense agreement with Papua New Guinea would appear strategically timed. As with the implementation of the DCA and the U.S. military use of the airport, it is unlikely that there will be any Chinese military activity at the site in the next 15 years – the duration of the agreement.

We face the question of whether CHEC continues to have any involvement or activity at the airport which may lead to potential intelligence gathering of Western military activity at Momote or the nearby Lombrum Naval Base. Under the 2017 National Intelligence Law, CHEC would be obliged to assist in intelligence collection on behalf of the PRC wherever it serves in the national security interest. We know that CHEC was the principal contractor for the project, and prime contractors are likely to be very competitive for future projects, such as upgrades and repairs, due to their command of the bidding process, technical expertise, and intimate knowledge of the airport specifications. This makes CHEC's return to the site likely if the airport requires further upgrades. According to an interview with a leading member of the Papua New Guinean Chinese business community, Chinese SOEs such as CHEC “enter the country to do a specific construction task, and then decide to stay on, and get selected for [jobs] because they fiercely undercut their competitors.” In 2019, CHEC had 20 infrastructure projects in Papua New Guinea, according to an interview with a CHEC employee, and ADB confirmed that Chinese SOEs held contracts for over 80% of ADB-funded development projects in the country. Furthermore, CHEC is active at bridge and road construction projects in Papua New Guinea, including work at the Ihu SEZ. With CHEC’s strong ties to Momote Airport and the company’s solid competitiveness in the infrastructure business in Papua New Guinea, it would be wise to vet all CHEC, or any SOE, personnel doing future work at the airport given the more robust U.S. military presence on Manus Island.

By projecting its military influence at Momote and Lombrum, the U.S. may have upended Beijing’s motivations for the airport and surrounding areas. However, the Momote Airport is not the only strategic location in Papua New Guinea in which the PRC sought to use its geoeconomic tools to secure a foothold. In our analysis of the next project, we observe Beijing’s financial commitments in the construction of the Ihu SEZ, in a likely effort to expand its influence and to create potential dual-use opportunities in the South Pacific nation.

IHU SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE

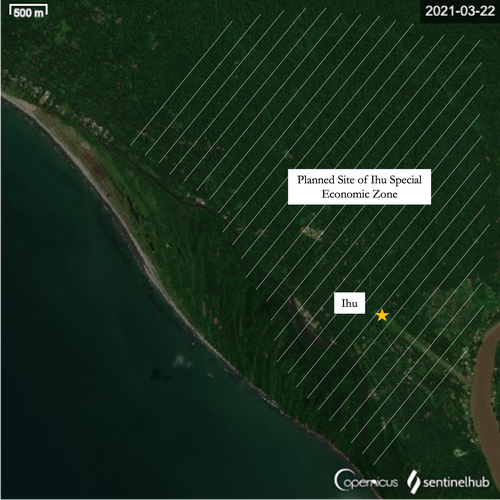

The proposed Ihu SEZ is an 85,000-hectare development project located near the town of Ihu in the Kikori District, along the southern coast of Papua New Guinea (see Figures 1 and 12).

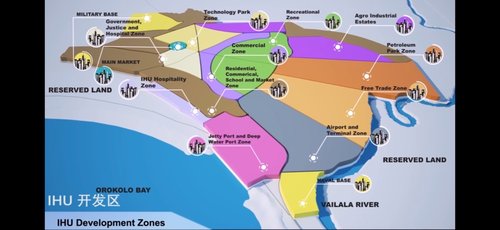

In 2019, during the initial phases of planning and securing funding for the project, the local Kikori District released a video promoting the Ihu SEZ in Mandarin and English text. The video included concepts for a naval and military base on the southern and northwestern edges of the SEZ (see Figures 13 to 15). From the presentation, it is unclear who the bases are for, but their inclusion is likely meant to appeal to Mandarin-speaking and English-speaking investors who might be interested in potential military access. As seen in Figure 13, the project also included proposals for other civilian zones dedicated to technology, petroleum, recreation, etc.

On September 24, 2021, the PRC committed a direct investment of 80 million Kina (K), or approximately 28.5 million USD, to the Ihu SEZ, which was used to kick-start the major access road development at the SEZ. In June 2022, the PRC committed to additional funding for the Ihu SEZ, bringing a welcomed early investment since the Papua New Guinea government reduced its original commitment from K100 million to K50 million. The government’s revised contribution is scheduled for distribution over five years, equating to only K10 million per year, significantly reducing the available funds for the project. As of mid-2022, China appeared to be the primary investor in the Ihu SEZ, providing more funding than the Papua New Guinea government. During the early stages of planning, three Chinese SOEs: CHEC, PowerChina, and the China Steel CSCEC, signed agreements to provide technical support to the Ihu SEZ project. CHEC is the same company that completed the renovations at the Momote Airport.

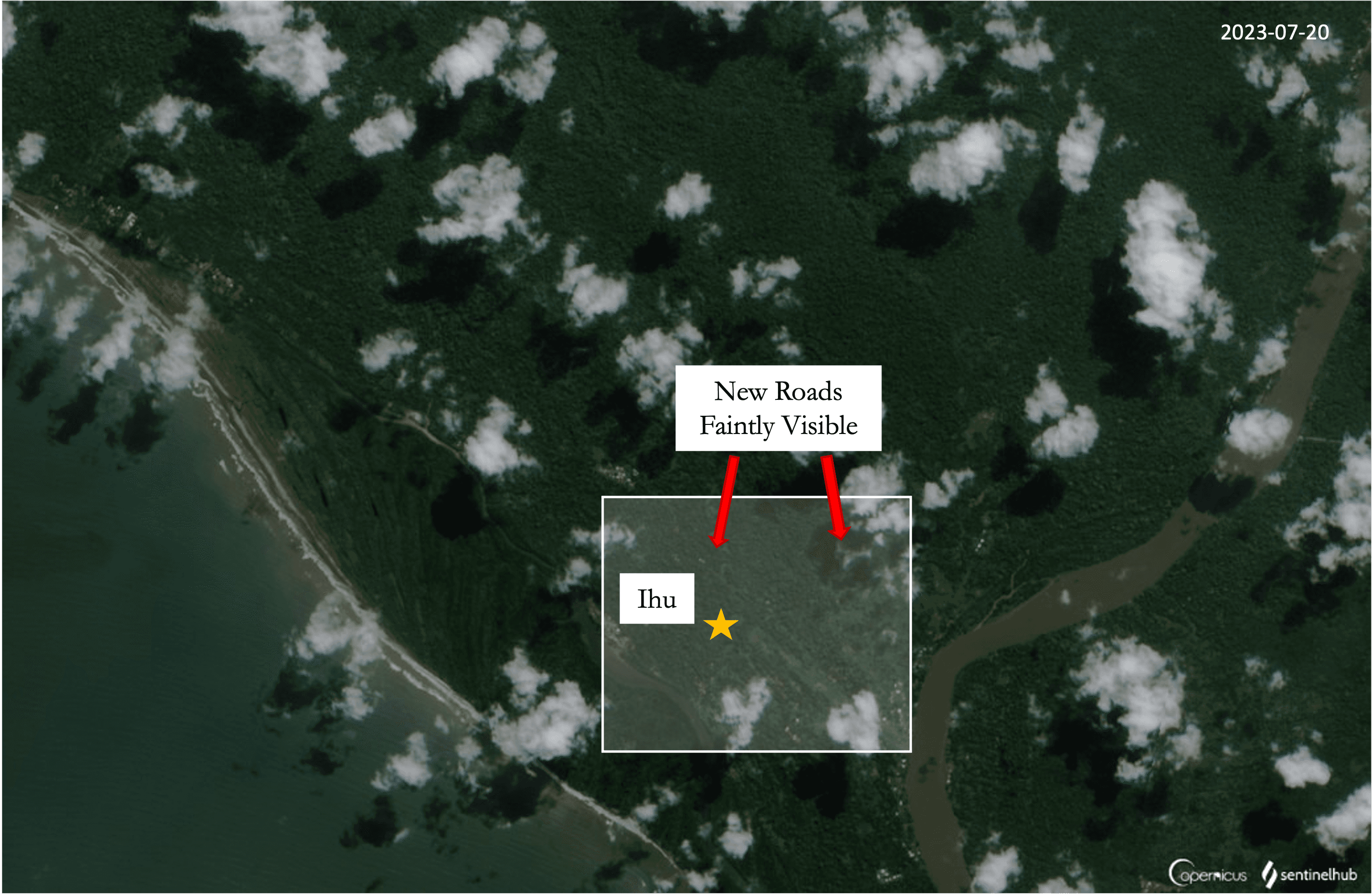

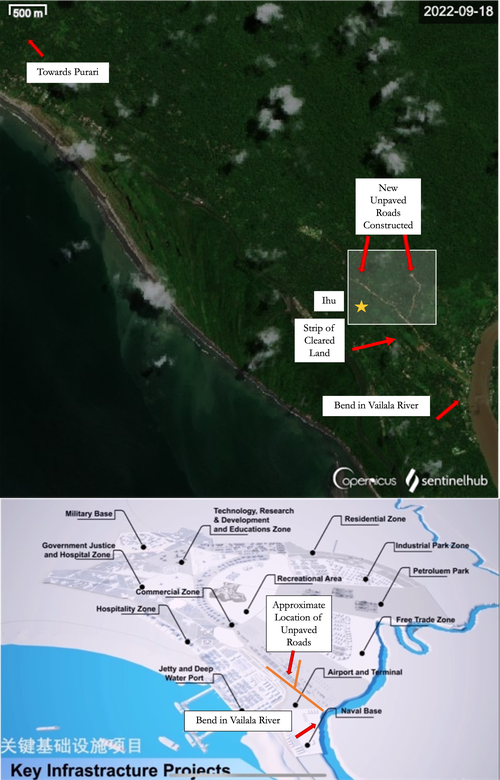

According to local Papua New Guinean media, the government approved the use of the K80 million investment by the PRC to start road construction between Ihu and Purari (also known as Kaumea), a project entrusted to CHEC and commenced in April 2022. Publicly available satellite imagery from March and September 2022 (Figures 16 and 17 [top], respectively) corroborates the local media report, illustrating the time frame in which an unpaved road, trending northwest to southeast along the path between Ihu and Purari, underwent construction. In the comparison in Figure 17, the new road in the top image appears to correlate with the area originally proposed for a naval base and airport in the bottom image, cutting through the center of the SEZ. The conceptual design for the naval base includes an airstrip adjacent to the base facilities and, in the future, may potentially align with the strip of cleared land bearing northwest to southeast in Figure 17 (top). In the following six months, between September 2022 and March 2023, there were no observable additional developments (see Figures 17 [top] and 18), and the roads appear overgrown with vegetation. In imagery from July 2023, the roads are faintly visible (Figure 19).

The imagery from September 2022 illustrates that the Ihu project made progress on road construction within a year of initial PRC financial investments, especially after Chinese Foreign Minister H.E. Wang Yi publicly made additional commitments to fund the Ihu SEZ in June 2022. Yet, the project may be experiencing some recent setbacks with road maintenance, as exemplified by the visible vegetative overgrowth in March and July 2023.

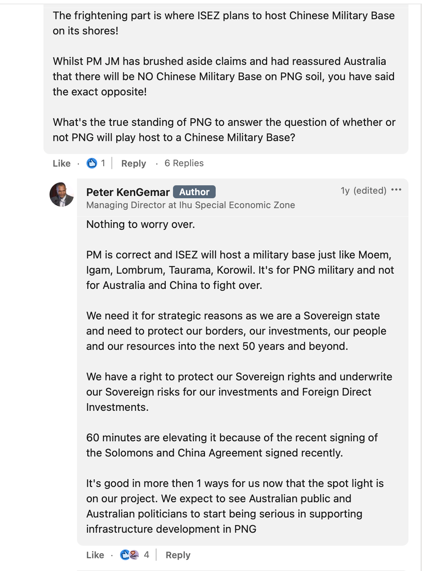

Unlike the Momote Airport, the Ihu SEZ project had explicit references to military use, as evidenced in the initial project proposals. Since the construction of the SEZ is still underway with signs of delays such as vegetation overgrowth on the roads, it is unclear whether the proposed naval and military bases will come to fruition. It is possible that the proposals were included merely to attract Chinese investment. In an Australian 60 Minutes interview in July 2022, the Ihu SEZ Project Director stated that if the Chinese “increase the amount of support they are giving…in the military space, then they might pick up those two bases,” referring to the proposed naval and military bases. The use of the term “pick up” may have implied that China would gain ownership or access to the two bases. This recorded comment, cast for Australian audiences, may have also been intended for Beijing, as it occurred in July 2022, one month after the PRC committed to additional funds for the SEZ. However, in response to public comments on his LinkedIn account expressing concern about a Chinese military base in Papua New Guinea, the Project Director walked back his previous statement. As shown in Figure 20, he stated that the “Ihu SEZ military bases will be for the PNGDF, not for Australia or China to fight over.”

It remains uncertain whether the proposed naval and military bases will be constructed and, if so, whether Papua New Guinea will permit access to China. Nevertheless, as the success of the project appears heavily dependent on Chinese funds, Beijing will likely have some influence on the project's plans and priorities.

CONCLUSION

China’s recent and future involvement in Papua New Guinea’s infrastructure projects should be cause for concern. The West has openly signaled its desire for military influence in Papua New Guinea, which can be seen in the signing of the DCA. In contrast, Beijing has been dismissive about its military interests in the country although its undertakings and economic investments include civilian infrastructure projects that have the potential to be used for military purposes such as the budding Ihu SEZ project.

The PRC could leverage CHEC’s project ties to Momote Airport to potentially gather intelligence on U.S. and Australian forces at the airport or the nearby Lombrum Naval Base. It is difficult to confirm CHEC’s continued involvement at the site and if the entity will send intelligence back to Beijing like in other situations animated by the 2017 National Intelligence Law. In the likely case that CHEC, who is a major infrastructure developer on the island and was the contractor during the airport renovations, will be present at the airport for future repairs or upgrades, it is important to screen contractors operating on the facility to minimize risks to Western militaries present in the area.

As for the development of the Ihu SEZ, disproportionate funding of the project suggests PRC’s potential interest in and influence on the future of the naval and military bases. Though, the Papua New Guinean project management has provided mixed messaging on whether China would have access to such bases. Moreover, analysis of current imagery does not support military base development at the Ihu SEZ. Rather, imagery illustrates only the early stages of the project, with the construction of poorly maintained roads.

As the DCA with the U.S. does not preclude Papua New Guinea from working with China, we may see Papua New Guinea continue to engage both parties and use their strategic leverage to extract resource commitments from both sides. We will likely see the PRC continue its economic investments in the island nation with possible acceleration to establish a stronger presence in Papua New Guinea in the face of the DCA. Whether their efforts achieve more power and influence in the area remains to be seen. In general, there is a rising discontent and resentment among the Papua New Guinea locals, including political and business elites, regarding Chinese migrants and businesses in the country. However, there were also local student protests in response to the signing of the DCA with the U.S., with the former Papua New Guinean Prime Minister saying the agreement "painted a target" on the nation. In the end, popular sentiment in the country may become a factor in determining which way Papua New Guinea will shift.

CONTRIBUTION NOTE

This report was made possible by the research contributions of GDIL researchers: Sofia Sandrea, Gunnison Hays, Steven Ahart, Cdr. Kevin Barrett, Zachary Daum, and Suraj Pandit.

May 22, 2023

The U.S. and Papua New Guinea sign the Defense Cooperation Agreement.

Papau New Guinea grants the U.S. military access to Momote Airport and Lombrum Naval Base.Source: Nikkei Asia

Nov 10, 2022

Papua New Guinea Prime Minister claims that “China has never expressed clearly their interest for a military base or presence of that nature in Papua New Guinea.”

Source: Bloomberg

Jul 11, 2022

The Chinese Embassy labels claims that China is building a military base in Papua New Guinea as “completely baseless and hype with ulterior motives.”

Source: Global Times

Jul 03, 2022

Ihu SEZ Project Director alludes to how the Chinese may “pick up” military bases if they increase financial support in an interview with "60 Minutes Australia."

Following public inquiries on social media, the Project Director then claims that any bases built would be for the Papua New Guinea Defence Force, not a foreign power.Sources: 60 Minutes Australia, LinkedIn

Jun 03, 2022

Chinese Foreign Minister H.E. Wang Yi publicly makes additional commitments to fund the Ihu SEZ.

Source: Loop PNG

Aug 26, 2020

China Communications Construction Company is added to the U.S. "Entity List" due to its role in aiding the Chinese militarization of the South China Sea artificial islands.

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce

Mar 21, 2019

Australia and Papua New Guinea sign Lombrum Joint Initiative Memorandum of Understanding.

Source: Australian Department of Defence

Jan 27, 2019

Papua New Guinea’s Kikori District releases a video promoting the Ihu Special Economic Zone (SEZ). Phase one of planning and funding begins.

Source: Kikori District

Nov 16, 2018

Former U.S. Vice President Mike Pence signals U.S. support for the Lombrum Joint Initiative with Australia.

Source: The White House

Sep 20, 2018

Australia and Papua New Guinea announce that they would undertake an Australia-funded upgrade of Lombrum Naval Base.

Source: South China Morning Post

Jun 22, 2018

Papua New Guinea officially signs a Memorandum of Understanding to join China's Belt and Road Initiative.

Source: Global Times

Jun 27, 2017

China passes National Intelligence Law, calling Chinese citizens and businesses to aid in national security matters and collect intelligence at the State’s discretion.

Source: Lawfare

Dec 19, 2016

China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) signs an agreement with Papua New Guinea’s National Airports Corporation to improve the Momote Airport.

Source: The National

Look Ahead

Monitoring future developments at the Ihu SEZ, especially which subzones are prioritized and if and when Beijing commits additional funding, will provide additional clarity to the PRC's intentions on the project. Also, analyzing Chinese activities in the neighboring Solomon Islands, with whom Beijing entered into a security agreement in April 2022, may present a broader picture of China's economic and military strategy in the South Pacific region.

Things to Watch

- How do China's financial investments in Papua New Guinea change in light of the DCA with the U.S.? If they decrease their investments, will China seek to increase its influence in nearby Pacific islands?

- How will local popular sentiment regarding foreign activity influence Papua New Guinean policy towards the U.S. and China?

About The Authors

Fellow at the Global (Dis)Information Lab & Senior Research Program Manager at the Intelligence Studies Project

Undergraduate Student at the University of Texas, Research Assistant at the Global (Dis)Information Lab

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.