Overview

In light of the European energy security crisis prompted by the War in Ukraine, this report provides an in-depth analysis of Russian involvement in North African oil and gas industries, focusing on five ongoing upstream projects across Algeria, Libya, and Egypt.

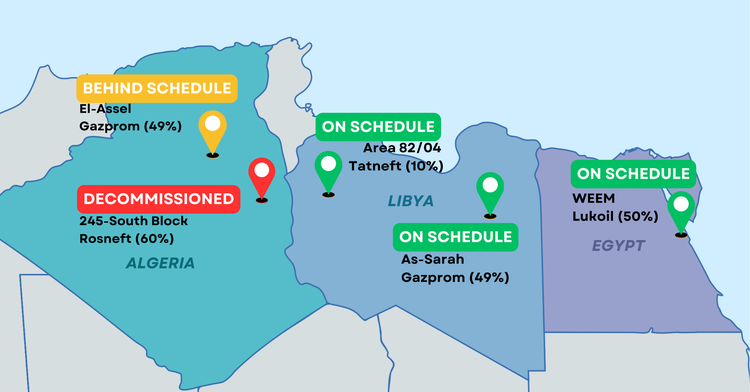

Imagery analysis reveals modest discrepancies between company reports and observed activities in 2 out of 5 ongoing projects. In Libya, the Area 82-4 and As-Sarah projects are on schedule. In Egypt, the West Esh El-Mallaha Project is on schedule. By contrast, in Algeria, the El-Assel Project is behind schedule and the Block 245-South Project is decommissioned.

Activity

This report analyzes commercial imagery, ground photography, social media, open press reports, and corporate documents to assess the progress of Russian-backed oil and gas projects in three North African countries: Algeria, Egypt, and Libya.

Introduction

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia's oil and gas industry has been a critical source of funding for the war. In order to weaken the Russian economy, the European Union (EU), the largest consumer of Russian hydrocarbons, imposed trade sanctions to cap the prices of Russian oil and gas exports. However, Europe cannot meet its energy needs solely through domestic production; in the year before the invasion, the EU imported 91.7% of the oil products and 83% of the natural gas products it consumed. Consequently, Europe has sought alternative suppliers to reduce its reliance on Russian imports, bringing North African countries like Algeria, Egypt, and Libya into focus.

For Russia, these countries have also become important for redirecting its hydrocarbon exports. Russian oil product exports to North Africa have surged, hitting all-time highs in mid-2023, representing a 144% increase from 2022 levels. Russian state-owned energy giants, such as Gazprom, Rosneft, Tatneft, and Lukoil, have further committed to several long-term agreements with national companies in Algeria, Libya, and Egypt. This dual focus on North Africa by both Europe and Russia necessitates a closer examination of ongoing Russian operations in North African oil and gas industries.

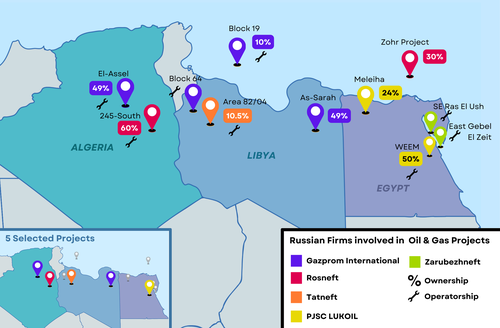

This report analyzes five ongoing oil and gas projects backed by Russian firms: El-Assel (Gazprom) and Block 245-South (Rosneft) in Algeria, Area 82-4 (Tatneft) and As-Sarah (Gazprom) in Libya, and West Esh El-Mallaha (Lukoil) in Egypt (See Figure 1.1). This report finds that three projects in Libya and Egypt are on schedule, while two projects in Algeria are behind schedule and decommissioned.

Methodology

The ongoing war in Ukraine has created rapidly shifting dynamics in the international oil industry that impact the reliability of secondary reporting on oil production. Compounded by existing issues from the COVID-19 pandemic, the conflict has led to soaring energy prices, disrupted oil and gas supply chains, and shortages of raw materials for energy infrastructure. Together, these factors impact both short-term and long-term project execution. At the strategic level, the conflict has also prompted long-term energy security concerns and geopolitical shifts as European countries strive to decrease their dependency on Russian oil, including new foreign investment flows in North Africa, as illustrated by the World Economic Forum. As a result of these disruptions, open press declarations and company reportings can often be incomplete or overstated. We will use satellite imagery analysis to build a more holistic assessment of the on-the-ground conditions of five selected Russian-backed oil projects in the region. We also wanted to use more precise language and analysis regarding Russia's oil and gas involvement in Africa which revolves around operating contacts, not export control. Export choices or pivots, especially changes prompted from Ukraine, lie with the home country not Russia. Russia has influence with sizeable investments and personnel present but do not control African export choices.

Background Information on the Oil & Gas Sector

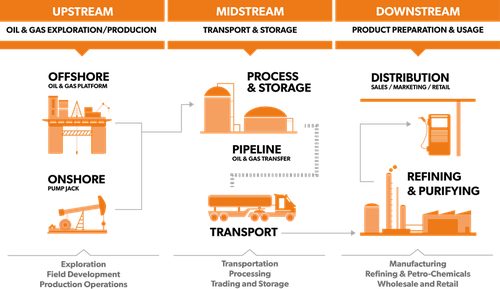

To contextualize our sampling and imagery analysis methods, an overview of the oil and gas industry is first necessary. The oil and gas industry, referring to crude oil and natural gas, has a supply chain divided into three segments: upstream involves extraction of oil and gas from the ground, midstream processes and transports them, and downstream refines and distributes them to consumers (See Figure 2.1 by cable company Eland Cables).

This study focuses on upstream projects that often house midstream processing facilities on-site, which is typical for remotely located projects according to a Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering article published in ScienceDirect. These projects, often lasting decades before production starts, involve substantial financial investments and extensive planning and advanced technologies to manage financial risks, according to oil industry training platform EKT Interactive.

Upstream projects search for and extract various hydrocarbons, including both crude oil and natural gas. Hydrocarbons can be discovered in distinct formations known as conventional fields, where oil and gas are found separately. More commonly, oil and gas are found together in various configurations. For instance, associated gas fields hold substantial quantities of oil accompanied by natural gas as a byproduct, while non-associated gas fields contain natural gas with minimal oil.

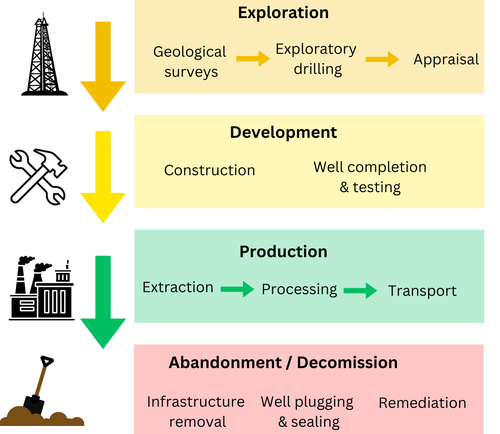

According to Italian oil firm Eni’s Exploration & Production (E&P) Division in 2019, while upstream activities are highly complex and dependent on project conditions, they have four general phases: exploration, development, production, and decommission, or abandonment (See Figure 2.2).

The exploration phase (1-5 years) involves identifying potential hydrocarbon deposits using geological surveys, then drilling exploration wells to assess the type and quantity of resources, according to Eni (See Figure 2.3 of drilling site from Pixabay).

When an exploration well yields commercially viable amounts of hydrocarbons, called an oil or gas field discovery, additional wells are drilled to further assess the size of the deposit in a process called appraisal (4-10 years). If no deposits meet company standards of commercial viability, operations are terminated, according to Eni, and exploration wells are sealed or plugged.

Development of the discovered deposit, or field development, is carried out after successful appraisal and before production begins, the Oil and Gas Portal says. The development phase (4-10 years) makes oil and gas extraction possible through the construction of material assets such as pipelines, processing facilities or plants, and completed wells, in which permanent equipment is installed through well completion (See Figure 2.4 of a completed well from Petroleum Engineering).

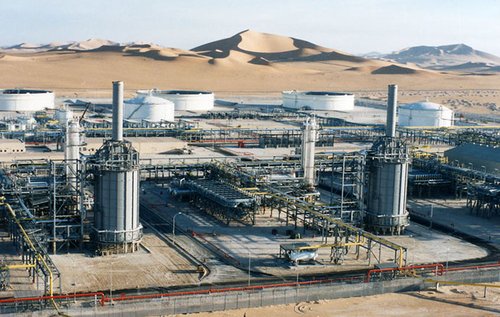

According to oil and gas data platform Greasebook, the deposit type and size determines the associated centralized processing facility, usually consisting of a central tank battery or a gas plant (See Figure 2.5 of central oil processing facility from JGC Holdings).

Once development is complete, production begins (20-40 years); hydrocarbons are extracted from the productive wells, processed in midstream plants, and sent to the downstream market via pipelines, according to Eni. Firms may conduct further development operations to boost production or install pumpjacks to increase flows to the surface as well pressure declines (See Figure 2.5 of pumpjack from OilPro).

Once deposits have been exhausted, a project faces abandonment (2-10 years), or decommission, involving the removal of associated infrastructure and well plugging. Our imagery analysis methods are based on this phase framework and explained in detail below.

Sampling Methods

Russian oil firms such as Gazprom, Tatneft, Rosneft, and Lukoil are engaged in 11 currently operational oil and gas projects across Algeria, Libya, and Egypt (See Figure 2.7). They hold partial ownership or operatorship status in four offshore and seven onshore projects. This report studies at least 50% of the Russian-backed onshore projects in each country, covering over 70% of all Russian-backed onshore projects in the region. It sampled two in Algeria (100% of Russian-backed projects in the country), two in Libya (60%), and one in Egypt (50%) (See Figure 2.7). Our sampling approach is designed to represent a wide spectrum of operations in North Africa and is influenced by several factors: the nature of the firm, the importance of each project within company portfolios, their location, and the reserve from which they extract.

We considered four leading Russian oil firms that are either fully or partially state-owned: Gazprom, Tatneft, Rosneft, and Lukoil. Projects were selected based on the significance of the firm’s involvement, owning at least 40% and holding operator status. This study only includes onshore projects given the majority of hydrocarbon production in the three countries is onshore.

Imagery Analysis Methods

To analyze the phase and activity levels of the selected contract areas, this report used commercial and public satellite imagery combined with secondary data analysis of local news reporting, corporate documents, and available contracts. This process involved building a detailed profile of the project using secondary research and analyzing satellite imagery over time to classify activity levels and project phases. By combining results, we determine whether the project is on schedule, behind schedule, or ahead of schedule baselined with corporate reporting.

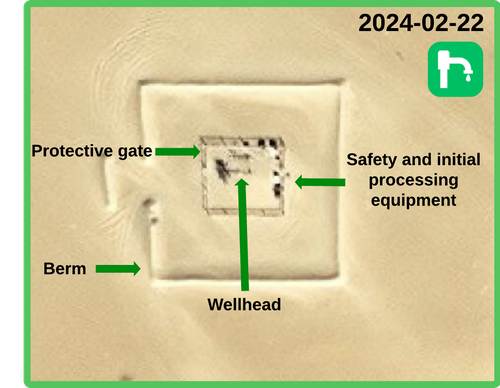

First, satellite imagery was analyzed to classify the activity levels of observed sites into one of three categories (active, inactive, or in development) in isolated periods (See Figure 2.8). This process consulted approximately 50 images total per project, from two years before the project start date to present. Activity levels of an infrastructure site were assessed using a set of indicators based on necessary infrastructure components, signs of maintenance, and signs of life or operational activity. The first indicator varies based on the type of infrastructure site, typically falling into three categories previously mentioned: well site, centralized processing facility, or drilling site. For instance, a well site is classified as active if essential extraction equipment can be identified; the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality's key well parts list includes a wellhead, initial separator, and protective gate (See example annotations of well components at El-Assel, Figure 3.1.4). By contrast, a centralized processing facility is considered active if it houses equipment for oil and gas gathering, separation, metering, and storage, which each entail a number of interconnected components explained in US oil equipment firm Kimray’s training video series (See example annotations of facility components at El-Assel, Figure 3.1.9). The last two indicators, signs of maintenance (i.e. connection to a cleared road network, de-sanding of the platform) and signs of life (i.e. cars parked at the well site, driving or parked on the connected road network) remain similar across site types to confirm active status. A site is classified as inactive when it lacks activity indicators and shows signs of abandonment, as previously explained. A site is considered in development when it progressively displays activity indicators along with evident signs of ongoing construction and activity, such as numerous parked trucks often containing equipment, site leveling, and the development of new access roads.

Next, based on our activity classifications over time, a project is classified into one of four phases (See Figure 2.8) mirroring those previously explained from industry literature: Exploration (Phase 1), Development (Phase 2), Production (Phase 3), and Decommission (Phase 4). The types of sites in the area and the timelines along which they become active, inactive, or in development signal which phase the project is in.

Finally, a comparison between the observed phase against that advertised in corporate reporting determines whether the project is behind schedule, on schedule, or ahead of schedule.

Our imagery profile and connected phases, based on observables, are not meant to replace corporate or business reporting on oil and gas. Imagery analysis simply adds another dimension to help estimate progress.

Russian Activity in Algeria's Oil & Gas Industry

Algeria, the second largest gas supplier to Europe and the second largest crude oil producer in Africa, is a pivotal player in the North African energy market. It houses two major hydrocarbon export pipelines to Europe, substantial oil and gas reserves, and has been a strategic partner for Russian energy firms like Gazprom and Rosneft since the 2000s. Despite maintaining strong political ties since the nations’ Declaration on Strategic Partnership in 2001, the relationship in the energy sector has been strained by competition due to both countries being major gas suppliers to Europe, according to a report by the Middle East Council on Global Affairs. However, Russian companies have remained active in Algeria’s energy sector since Algeria’s first international hydrocarbon exploration and production tender in 2001, engaging in projects spanning oil exploration to gas plant construction. As European nations consider pivoting to Algeria as an alternative energy supplier in light of Ukraine, the Russo-Algerian relationship as well as internal economic struggles cast doubt on Algeria’s ability to increase exports to the EU, according to Fordham Professor Geoff Porter in 2022. If successfully developed and kept on track, Russian-backed oil & gas projects could form a new partnership that secures Russia’s stake in one of Europe's critical alternative energy markets.

El-Assel Project: Joint Venture between Gazprom International & Sonatrach

Imagery analysis reveals that the El-Assel project in eastern Algeria, a joint venture between Gazprom International and Sonatrach, is in Phase 2, Development, and is behind schedule as of April 2024. This section will explain these findings by comparing corporate reports to imagery in 4 steps: well activity, processing facility activity, phase classification, and schedule classification.

Location, Description, & Context

The El-Assel upstream oil & gas project in Algeria’s Berkine Basin, developed under a joint venture between Gazprom International and Algeria's national oil corporation Sonatrach, represents a strategic investment for Russia in North Africa. Notably, El-Assel is Gazprom’s first significant stake in the region and one of the largest among its Russian counterparts, totaling $1 billion USD, according to July 2023 Asharq Al-Awsat article recounting Russian Energy Minister Nikolai Shulginov’s interview with Russian news agency TASS.

The firms have been collaborating at El-Assel for nearly two decades. According to Gazprom’s reports, it was awarded a 49% stake and operatorship of El-Assel in 2008 through Algeria’s first national and international Exploration & Production (E&P) tender conducted by Algeria’s National Agency for the Valorization of Hydrocarbons (ALNAFT). The project underwent the exploration phase from 2009-2016, followed by development from 2016-2022. According to Gazprom reports, El-Assel is set to start production in 2025-2026.

Key Findings

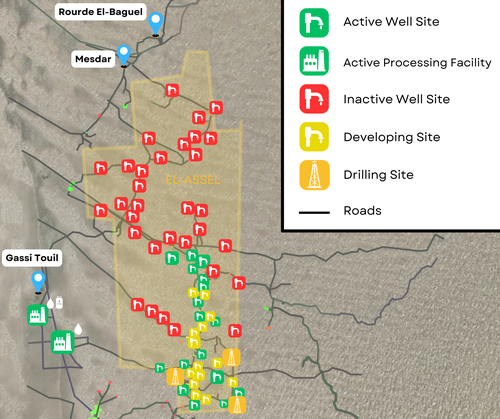

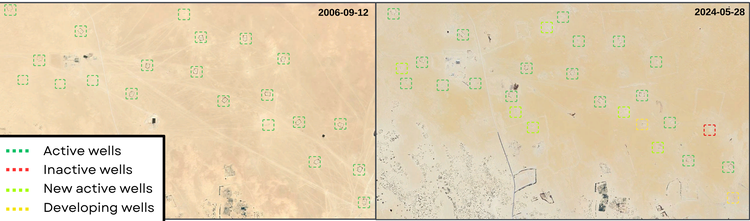

Imagery analysis reveals that as of March 2024, there are 20 active wells, 31 inactive well sites, 10 developing wells, 3 drilling sites, and 2 active processing facilities in El-Assel. (Overview of sites in Figure 3.1.1). To determine these activity levels, imagery of each site was anlayzed over time, noting infrastructure components, signs of maintenance, and signs of operational activity at the site.

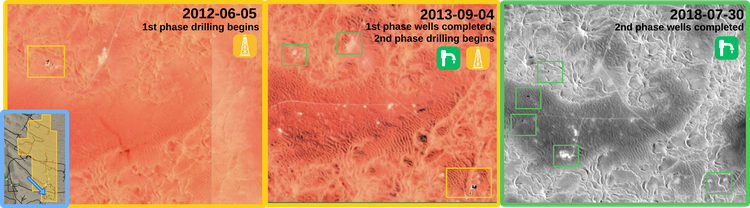

Imagery shows that 61 well sites are distributed across El-Assel over an 80 kilometer stretch from north to south. Mostly grouped in northern El-Assel, 31 wells were found to be inactive as indicated by being sealed with cement, surface infrastructure removed, connected road networks covered in sand, and no signs of operational activity within a 0.5 kilometer vicinity (see Figure 3.1.2).

Imagery further shows that these wells were drilled and abandoned within 12 months between 2011-2016 (see Figure 3.1.3), which is a typical exploration practice when wells do not yield commercially viable flows of hydrocarbons, according to the Oil Blog Drilling Manual. These timelines coincide with Gazprom’s reported exploration operations in 2009-2016.

Located in southern El-Assel, imagery shows that as of 2024, there are 30 active well sites that undergo frequent maintenance and contain key well infrastructure, including a wellhead, protective gate, initial processing equipment, and gas flare (See Figure 3.1.4).

In 2014, Gazprom reported that it had made two oil discoveries in recent years, in 2010 at Rhourde Sayeh and in 2014 at Rhourde Sayeh Nord, and imagery shows that the 31 active wells were drilled in two phases–2010-2012 and 2013-2016–that likely reflect the appraisal process following each discovery (See Figure 3.1.5). As mentioned, appraisal is conducted during the exploration phase after a discovery to collect data on the discovered field, which entails drilling multiple new wells across a wide area, according to EnergyHQ.

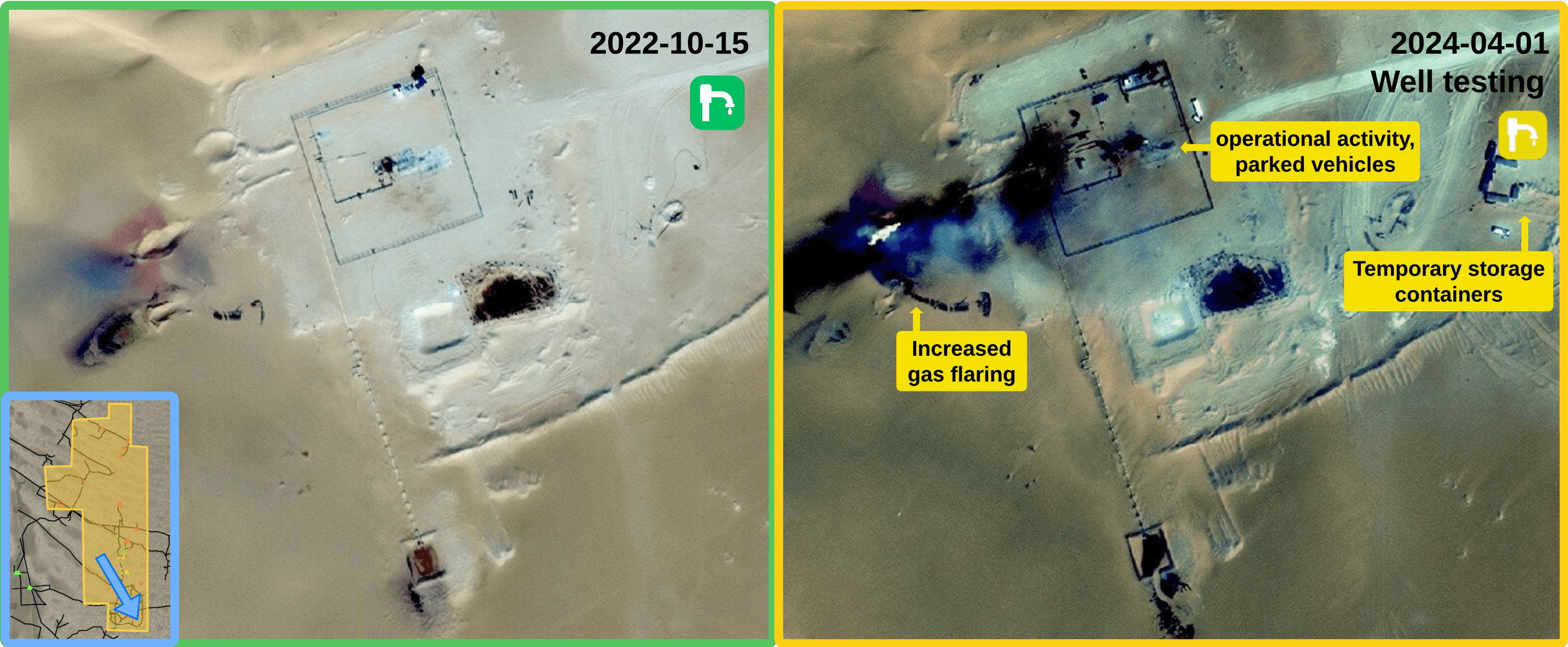

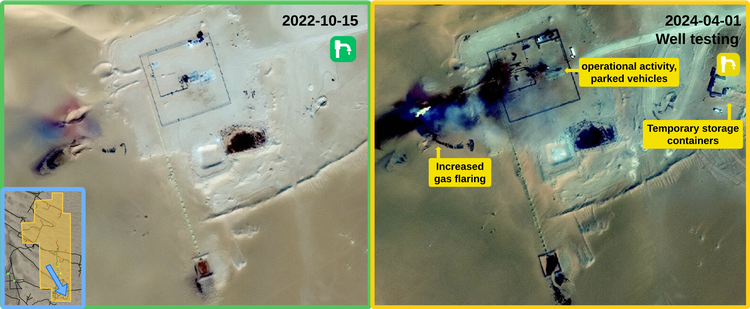

In the same area, imagery further shows 10 developing wells in 2024 that are at different stages of well completion. Some developing wells show signs of well testing (See Figure 3.1.6). Well testing is commonly performed to collect data on oil flows before a well is completed and entails increased gas flaring (See Figure 3.1.6) to burn hydrocarbons exceeding supportable levels when there is no immediate infrastructure to process or transport it, according to the U.S. Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council.

In addition, imagery shows four drilling sites (See 2 examples in Figure 3.1.7, 3.1.8), with operations starting in 2021. These findings, coupled with developing wells, are consistent with Energy Voice and Reuters reports of Gazprom’s 2021 development phase plans for the Rhourde Sayeh discoveries, which include the drilling and completion of 24 wells.

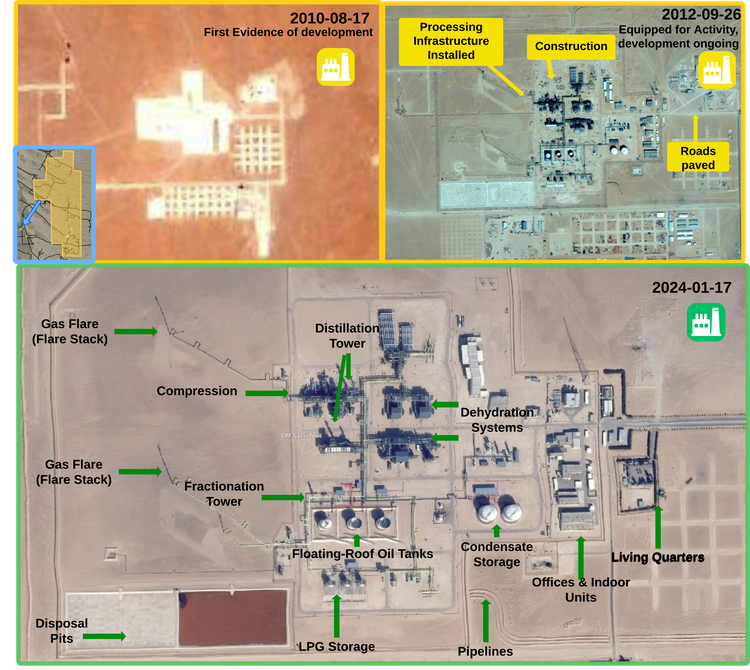

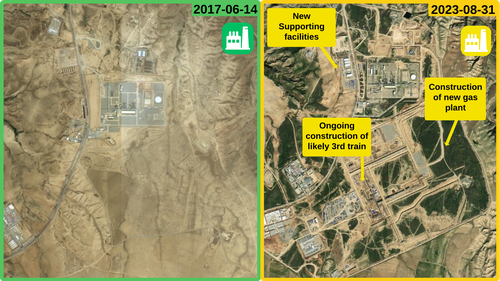

Forty-eight (48) kilometers east of the wells, imagery indicates there are two currently active processing facilities. By analyzing the infrastructure components observed at each facility, we find that only one has the capacity to process oil and liquified petroleum gas (LPG) products, which is indicated by gas gathering and separation equipment such as distillation towers and compressor units. This facility underwent construction in 2010, contained key gas processing infrastructure by late 2012, and has since remained largely unchanged as of January 2024 (See Figure 3.1.9).

Equipment analysis and Google Maps geotag titled 'CPF de Gassi Touil' (Central Processing Facility) suggests this facility to be the Sonatrach-operated Gassi Touil gas plant completed by Japanese JGC Holdings in 2013, reportedly handling gas gathering and separation for 52 connected gas wells from neighboring contracts (See Figure 3.1.10). The facility's distance to the wells (48 km) is common in remote settings, according to oilfield design articles by Keystone Synergy, the plant is located at El-Assel's access point (Base Gassi Touil), and it underwent construction during the contract period. Thus, while the 52 connected gas deposits are not explicitly listed, we judge with moderate confidence that El-Assel's extracted gas could be processed at this facility once wells are completed. These findings confirm the construction of a natural gas plant cited in Gazprom’s 2021 development plans, as reported by Energy Voice.

Located 8 kilometers south of the gas plant, the second facility supports water and chemical injection, and has remained largely unchanged since 2003 (See Figure 3.1.11). Given its proximity and connected roads to the first, imagery suggests this facility is likely a secondary processing and storage site.

Combining the above analyses, we conclude that El-Assel is in late Phase 2, Development, for three reasons. First, the ongoing drilling and well testing shown in imagery is usually completed before well completion since its purpose is to confirm commercial viability before gearing up for production, according to the Oil and Gas Portal. As previously mentioned, the associated gas flaring seen at many wells also indicates the absence of immediate processing infrastructure, suggesting processing equipment has yet to be installed in direct proximity to many wells. Second, the lack of infrastructure development at the gas processing facility in tandem with well completion, typically done when connecting a plant to new production wells, suggests that existing processing infrastructure has yet to be developed to account for increased gas flows. It follows, third, no surface or pipeline construction being identifiable in a 16-kilometer vicinity of the wells indicates that a permanent pipeline network has yet to be installed.

For comparison, the Khor Mor gas plant in Iraq was significantly expanded to account for new connected gas wells. According to NS Energy, Khor Mor first underwent a development phase from 2007-2011, including the construction of six gas wells and a gas processing plant. In late 2018, the KM-250 expansion project was initiated to enhance processing capacity, NS Energy writes, accounting for increased flows from four new gas wells (See Figure 3.1.12).

Completed in April 2024 according to a Kurdistan 24 article, the expansion entailed enhancements to the gas plant’s storage and truck loading stations and the construction of a new adjacent gas processing unit, also called a gas train (See Figure 3.1.12, 3.1.13). The added production is larger than that projected for El-Assel (14 million cubic meters per day (Mcmd) vs. 2 Mcmd of natural gas, according to Russian news agency Agenzia Nova and oil and gas publication Hydrocarbons Technology) yet still shows that additional production often requires enhancements and additional construction.

This phase suggests a slower timeline compared with Gazprom reports that full-scale production will start in 2025. We judge with confidence that the project is modestly behind schedule, which would align with recent news reports from June 2023 (Agenzia Nova, Embassy of Algeria to Croatia) that production is now set to begin in 2028. Further, in Gazprom reports, the pipeline infrastructure connected to the 24 new wells will be developed before production starts and pipeline construction can take several months to years for a simple two-ended pipeline, according to Engineering firm Fenstermaker.

245-South Block Project: Joint Venture between Rosneft & Sonatrach

Imagery analysis reveals that the 245-South Block project in southeastern Algeria, a joint venture between Rosneft and Sonatrach, is in Phase 4, Decommission, and is likely canceled as of February 2024. This section explains these findings by comparing corporate reports to imagery in four steps: well activity, processing facility activity, phase classification, and schedule classification.

Location, Description, & Context

The Block 245-South project, located in the Ohanet area of the Illizi basin, was the first hydrocarbon investment under Russian ownership in Algeria and the only one in the region with a Russian majority stake. Rosneft invested a significant $1.3 billion USD in the development phase, according to a 2007 announcement by Rosneft’s Vice President Nikolai Borisenko reported by Reuters.

Rosneft, initially part of a consortium with Russian firm Stroytransgaz, was originally awarded operatorship and a 60% stake of 245-South in 2001 under a joint venture with Algeria's Sonatrach (40%), as reported by Russian news source Oreanda. From 2001 to 2010, the project was in the exploration phase, undergoing geological testing (2001-2007) and appraisal (2009-2010) which resulted in three oil and gas condensate discoveries, according to Russian news source Vedomosti. While ALNAFT originally approved field development plans for 2009-2012, the development phase only began in 2012 due to extended testing, according to Rosneft reports. That year, Russian newspaper Kommersant reported that Stroytransgaz sold its 50% stake in the 245-South joint venture to Rosneft, leaving development between Rosneft and Sonatrach.

Key Findings

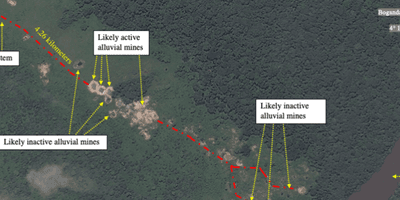

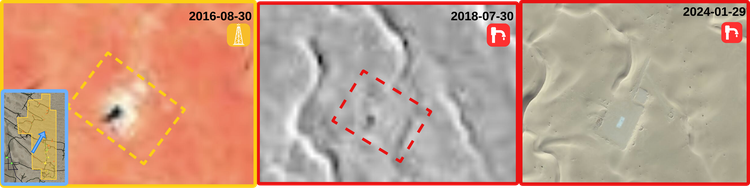

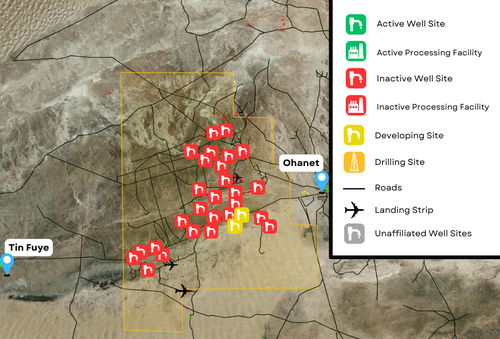

Imagery analysis shows that as of April 2024, there are over 20 inactive well sites and three developing sites in the contract area (See overview in Figure 3.2.1). All well sites in Block 245-South are inactive with their surface infrastructure removed, perimeter areas remediated, and connected road networks abandoned, as indicated by sand covering (See Figure 3.2.2).

Imagery further shows that many wells were drilled between 2009-2012, but abandoned by 2016-2018 (See Figure 3.2.3). The observed drilling period aligns with Rosneft reports of appraisal in 2009-2010 following the three discoveries, which, as mentioned, involved the drilling of multiple new wells to collect data on the discovered fields. Imagery observations also comport with Rosneft and Russian oil publication Rogtec reports of development operations in 2012, the plans for which included, according to Oreanda, the three discovered fields being "put into operation," meaning wells would be drilled and completed in preparation for production.

The decommission of wells observed in 2016-2018, however, does not reflect Rosneft reports of the project still undergoing development, their latest press release dating back to 2012. Field development involves well completion and the installation of surface facilities to begin production. Contrarily, imagery shows widespread equipment removal in 2016-2018, suggesting that further development ceased in that period (See Figure 3.2.3). According to an Africa Energy Intelligence report from 2017, the Algerian government ordered ALNAFT to handle a dispute between Rosneft and Sonatrach over lack of progress at 245-South; Rosneft, reportedly "strapped for cash" due to oil prices plummeting in 2014, fell significantly behind in development operations and Sonatrach planned to cancel the contract or sell Rosneft's share if they did not begin production by the end of 2017. Imagery aligns with the likely scenario in which Sonatrach canceled production by the end of 2017.

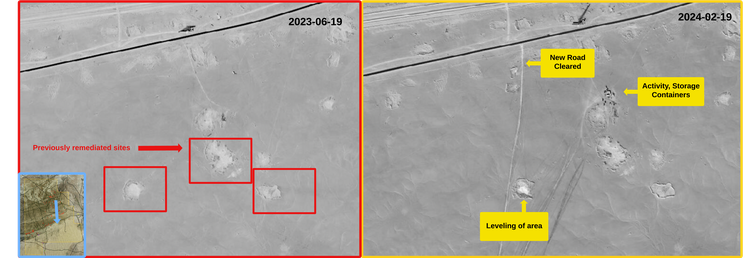

Interestingly, recent imagery indicates new development activities in 2024 such as ground leveling and road clearing in the southern region of Block 245-South (See Figure 3.2.4), five kilometers south of the highway connecting Ohanet and Tin Fuye (See overview in Figure 3.2.1). Construction is too preliminary to determine what sites are being developed. Should these become oil and gas sites, which is likely considering the number of inactive wells in the area, these findings suggest three possible scenarios: a new actor has taken up the project, Sonatrach has resumed activity independently, or the joint venture has resumed operations after a six-year hiatus.

Despite this new uptick of activity, overall, imagery analysis reveals that the 245-South Block project is in Phase 4, Decommission. This phase is indicated by all well sites having been inactive for six years, the lack of extraction and processing equipment in the area, and minimal signs of operational activity since 2018. The new developments noted in Figure 3.2.4 are minimal, recent, and likely reflect activity by a new actor or Sonatrach independently. Considering the mentioned financial risks and operational costs associated with upstream's long project timelines, it is unlikely that infrastructure would be entirely disassembled and rebuilt six years later under the same development contract. According to anonymous sources in 2017 articles by Russian news publication Kommersant and energy news source OilPrice.com, Rosneft made an unsuccessful attempt to sell its stake in 245-South to Gazprom and went on to discuss its complete withdrawal from Algeria projects.

Conclusion for Algerian Projects

Russian involvement in Algeria's oil sector through projects like El-Assel and 245-South underscores a strategic effort to secure influence in North Africa’s energy market. In the words of Gazprom CEO Surgey Tumanov, “A successful implementation of the [El-Assel] Project can…serve as a basis for expanding the company's presence in [the country] … this may be an incentive for other Russian players to come to Algeria.” Gazprom’s El-Assel project highlights both the potential and the challenges of this partnership; despite initial progress and substantial investment, inconsistencies in production timelines may indicate ongoing hurdles. Similarly, Rosneft’s Block 245-South project which initially paved the way for Russian investment in the country, has been decommissioned. While projects can face decommissioning due to poor findings in the early development phase, Kommersant and Africa Energy Intelligence reports suggest it could be a symptom of the partnership’s efficiency. At any rate, the downturn of 245-South reportedly resulted in Rosneft's exit from Algeria, equating to a several-hundred-million-dollar write-off. Overall, these projects show that Russian-backed projects in Algeria can, at times, fall behind schedule or be canceled outright.

Russian Activity in Libya’s Oil & Gas Industry

Libya's oil and gas sector holds significant potential and strategic importance as the third-largest petroleum liquids producer in Africa and holding the continent's largest proven oil reserves at 48 billion barrels. Despite these advantages, ongoing civil unrest and political instability have severely limited investments and development since the 2011 civil war, according to the United Nations (UN) Security Council Report. Russian state firms like Tatneft, Gazprom, and Rosneft have signed or renewed agreements for oil and gas production since 2021, reinforcing Russia's strategic foothold in Libya’s energy sector. As European nations look to Libya as an alternative energy source in light of Ukraine, Libya's internal power struggles and Russian backing of the country’s divided government, particularly through energy sector cooperation, could allow Russia to exert political pressure on oil-dependent nations and manipulate oil prices, as highlighted in Bloomberg and Georgetown Security Studies articles.

Area 82-4 Project: Joint Venture between Tatneft & Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC)

Imagery analysis reveals that the Area 82-4 project in western Libya, a joint venture between Tatneft and Libya’s NOC, is in early Phase 1, Exploration, and is on schedule as of April 2024. This section explains these findings by comparing corporate reports to imagery in four steps: well activity, processing facility activity, phase classification, and schedule classification.

Location, Description, & Context

The Area 82-4 oil exploration project, located in Libya's Ghadames Basin, signifies a crucial Russian investment in Libya’s oil sector. Tatneft's entry marked the first Russian-backed project to resume operations in Libya post-2011 civil war, reflecting a strategic effort to re-establish Russian influence in the region.

Tatneft began operations at Area 82-4 in 2005, signing a 30-year Exploration and Production Sharing Agreement (EPSA IV) with Libya’s NOC that granted the firm operatorship and a 10.5% stake. The project entered the exploration phase in 2005 but operations were halted in 2011 due to Libya's civil war. After a decade-long pause, Tatneft resumed exploration in 2021. Two years later, Tatneft’s Deputy CEO Nurislam Syubaev reported a discovery at the exploratory well F1-82/4 in an interview with TASS which was confirmed by the NOC Media Office, according to Libyan news outlet Libya Herald. Syubaev further noted, “We are now doing cost efficiency calculations. If they are positive, we will move to the pilot development stage.”

Key Findings

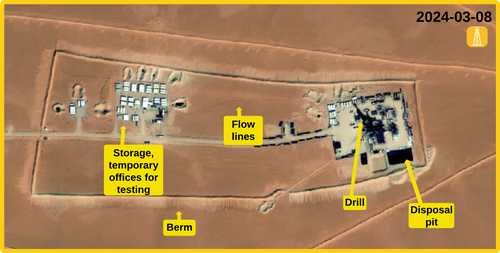

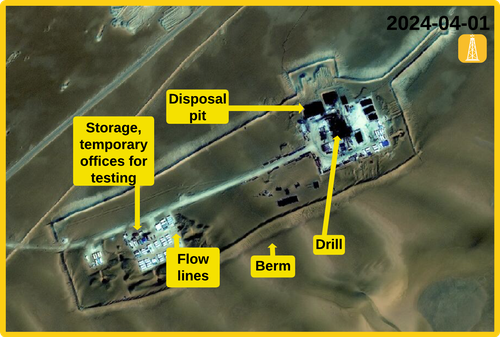

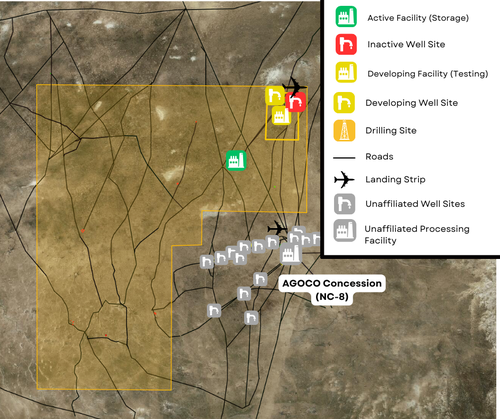

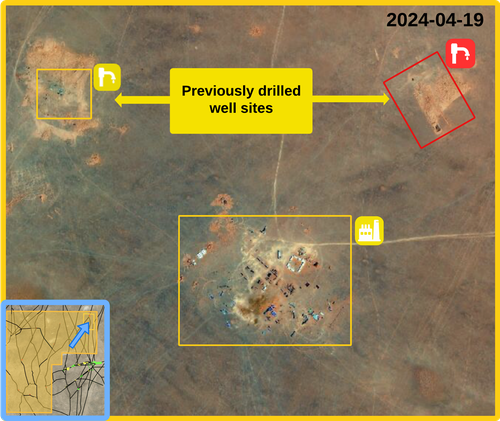

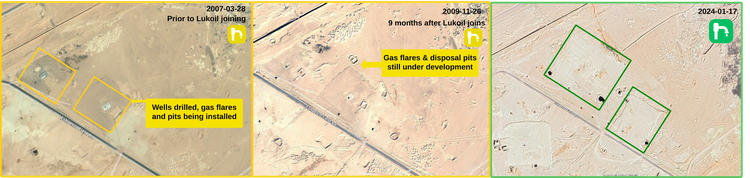

Imagery shows that as of April 2024, Area 82-4 contains one developing well site, one inactive well site, one developing facility, and one active facility (See overview of sites in Figure 4.1.1). The two facilities are likely supporting sites for testing and equipment storage, rather than processing plants.

The developing well and inactive well are 500 meters apart in the northwestern region of Area 82-4 (See Figure 4.1.2).

Imagery of the western developing well shows that it was drilled in early 2011, halted later that year, and resumed in late 2020 (See Figure 4.1.3). This coincides with Libya's NOC and Libya Herald reports from 2021 saying Tatneft completed drilling at the B-2 well in October of that year after a 10-year hiatus due to the civil war. Imagery shows that drilling equipment was removed and replaced with temporary well completion equipment (See Figure 4.1.3), which is typically done when testing the commercial viability of an exploration well, according to the American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

A half kilometer (0.5) west, the second well is shown to contain the same temporary completion equipment (See Figure 4.1.4), but we find that it is currently inactive given it has remained unchanged and seen no signs of operational activity since it was drilled in 2007.

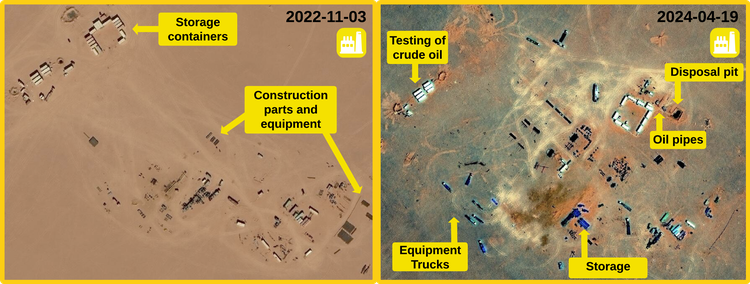

A half kilometer (0.5) south of the wells, imagery shows a developing facility with construction parts, disassembled drilling equipment, testing equipment, and numerous vehicles (see Figure 4.1.5). The facility appears in 2022 after the previously mentioned drilling operations were completed and shows an increase in processing infrastructure over time, suggesting that it is likely used for testing flows from the developing well. These findings reflect corporate news publication Arabian Gulf Business Insight reports of the oil discovery in 2023 previously mentioned, that claim Tatneft is currently conducting testing on the new well to determine its commercial viability.

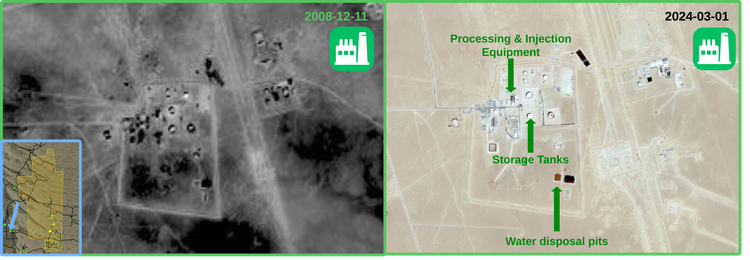

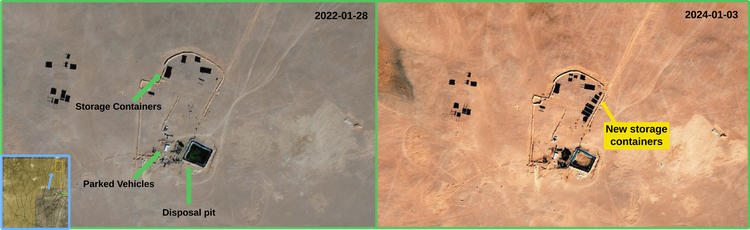

Twenty (20) kilometers southwest of the testing facility and connected by tire tracks, imagery shows an active facility that stores changing quantities of construction equipment and lacks processing equipment beyond a water disposal pit (See Figure 4.1.6). This suggests it is likely a storage site for the drilling and testing operations mentioned above.

Overall, these findings suggest Area 82-4 is in Phase 1, Exploration. This judgement is based on the low number of observed well sites, lack of completed well infrastructure or processing plants, and ongoing testing operations near a recently drilled well. This combination is unique to the exploration phase, when testing is conducted to confirm significant oil deposits before further exploring or developing the area, as explained earlier. This phase aligns with Tatneft reports documented in the Libya Herald of Area 82-4 being in the exploration phase since the 2023 discovery, and thus we judge with confidence that the project is on schedule as stated in corporate reporting.

As-Sarah Project: Joint Venture between Gazprom International, Wintershall DEA, & Libya’s NOC

Imagery analysis reveals that the As-Sarah project in eastern Libya, a joint venture between Gazprom, Wintershall DEA and Libya’s NOC, is in Phase 3, Production, and is on schedule as of May 2024. This section explains these findings by comparing corporate reports to imagery in four steps: well activity, processing facility activity, phase classification, and schedule classification.

Location, Description, & Context

The As-Sarah oil project, located in the Sirte Basin near the oasis settlement of Jakharrah, is an example of Russian involvement in the Libyan oil sector through partnerships with other international oil corporations (IOCs). The project was established as a joint venture between Gazprom, German company Wintershall DEA, and Libya’s NOC.

According to Gazprom reports, the firm originally joined the project with Wintershall in 2007, gaining operatorship status and a 49% stake in the project. At the time Gazprom joined, As-Sarah had already been in the production phase under Wintershall DEA's individual contract since 1989. The partnership boosted ongoing production by conducting further development of the area, reporting nine new oil and gas discoveries. Following disruptions from the 2011 civil war, Gazprom’s CEO Sergey Tumanov told TASS in 2018 that the partnership had resumed operations, confirmed by Reuters reports. In 2023, Gazprom reported that pre-civil war production levels had been restored.

Key Findings

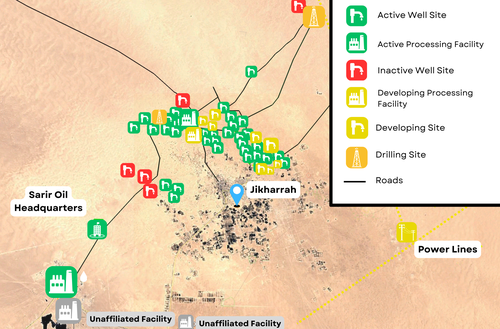

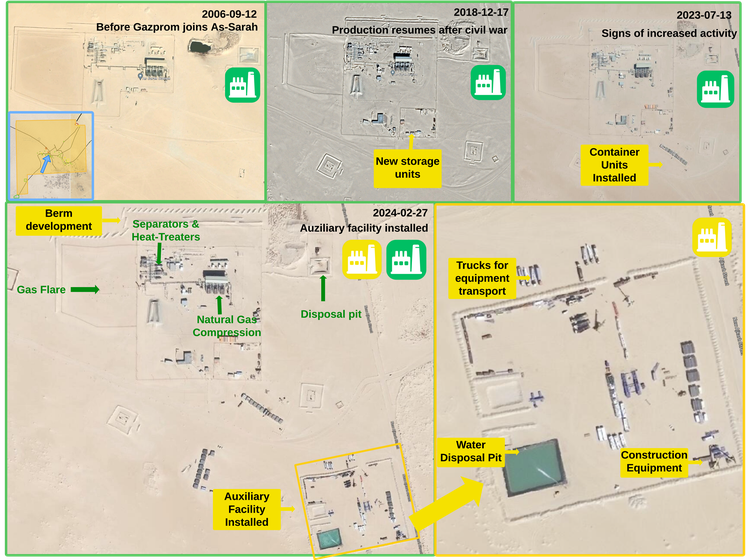

Imagery of the As-Sarah project suggests that as of May 2024, there are approximately 24 active wells, four inactive wells, eight developing wells, two drilling sites, two active processing facilities, and one developing auxiliary facility (See Figure 4.2.1).

Imagery shows that 24 well sites, located 3.5 kilometers north of Jikharrah, are currently active, as indicated by key extraction equipment previously explained (See Figure 4.2.2).

The observed number (24) of active wells reflects Gazprom reports of 24 active well sites at As-Sarah, and imagery further suggests many underwent maintenance since Gazprom resumed operations (See Figure 4.2.3).

Imagery also shows that 80% of the active wells existed prior to Gazprom joining the project in 2007, and one well site has since become inactive and five new well sites were added (See Figure 4.2.4).

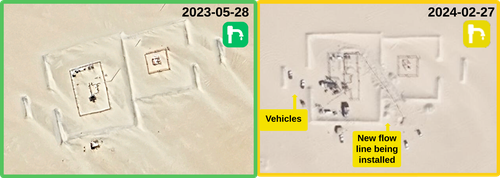

Moreover, imagery of the eight developing wells shows they underwent development starting in 2021, the year Gazprom reports it resumed operations, with imagery indicating increased maintenance activity, installation of new flow lines, and construction (See Figure 4.2.5).

Imagery also shows ongoing drilling at two sites as of February 2024, one in the northeastern corner of the well cluster and one eight kilometers northwest (See example in Figure 4.2.6). In contrast to exploration phase drilling, these drilling sites represent development operations conducted in the production phase to boost ongoing production, indicated by well infrastructure already in place in close proximity (See Figure 4.2.6). Imagery specifically suggests infill drilling, which involves drilling near pre-existing wells to increase flow paths to the surface according to SLB Energy Glossary, aligning with reports by Gazprom.

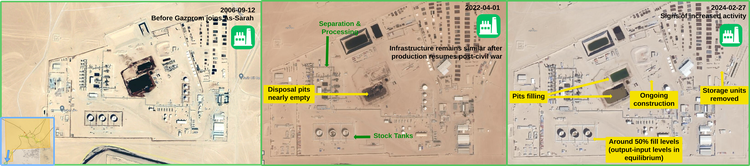

Imagery suggests that As-Sarah contains two active processing facilities that were already operational prior to Gazprom joining the project in 2007. The facility in closest proximity to the active wells, located 3.5 kilometers north of Jikharrah, has maintained the same core processing components since 2006, with the exception of an auxiliary facility added 0.2 kilometers to its south in 2024. However, this site does not host any processing infrastructure beyond a water disposal pit, and is likely used as a storage site (See Figure 4.2.7).

Thirteen (13) kilometers southeast of this facility, imagery shows a larger facility that has key oil and gas processing components and larger storage units (See Figure 4.2.8). Imagery suggests that it has remained largely unchanged since before Gazprom joined (2006), and shows increased operational activity since operations resumed in 2021 (See Figure 4.2.8).

Overall, these findings suggest that As-Sarah is in Phase 3, Production. This phase is indicated by As-Sarah's longstanding (18 years) processing facilities and completed wells which aligns with the duration of the production phase (20-40 years) explained earlier. Additionally, the observed infill drilling is typically completed well into in the production phase to stimulate decreasing oil flows. This phase aligns with Gazprom reports of full-scale production resuming in 2021 and restored to pre-civil war levels by 2023, thus we judge with confidence that the As-Sarah project is on schedule.

Conclusion for Libyan Projects

Overall, Russian engagement in upstream exploration operatorships like Tatneft’s Area 82-4 and the revitalization of production projects like Gazprom’s As-Sarah suggest a long-term commitment to tapping Libya's substantial oil reserves. The success of Tatneft and Gazprom collaborations in Libya’s recently stabilized political climate positions Russian firms to pursue further agreements with Libya's NOC. Moreover, the renewal of long-term agreements of the two projects shows that their presence in Libya’s oil sector is guaranteed through the medium term. However, Russian state companies operate as minority partners in joint ventures or under production-sharing deals with Libyan state entities, limiting their direct control while still allowing some influence aligned with their interests.

Russian Activity in Egypt’s Oil & Gas Industry

Egypt, the twelfth largest natural gas producer globally and the third-largest in Africa, is a significant player in the global energy market with reserves of 63 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and about 3.3 billion barrels of crude oil. Egypt’s energy sector is also supported by significant export channels through the Suez Canal and SUMED pipeline. Although Russian firms like Zarubezhneft and Lukoil have been investing in Egypt’s oil and gas sector since the early 2000s, particularly at the West Esh El Mallaha (WEEM) oil project, Russian investment has been on the rise in recent years with Egypt’s potential as an energy supplier. Due to economic challenges under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's rule, Egypt has pursued major energy sector development to attract foreign investment, to which Russia has been a significant contributor. While this study focuses on onshore oil projects, Russia has been involved in significant projects on a broader scope, including Rosneft’s Zohr offshore gas project and Rosatom’s El-Dabaa nuclear power plant. Ultimately, Egypt's reliance on Russian debt financing for major energy infrastructure projects poses long-term economic risks and complicates Europe’s energy pivot from Russia, according to the Atlantic Council in 2024.

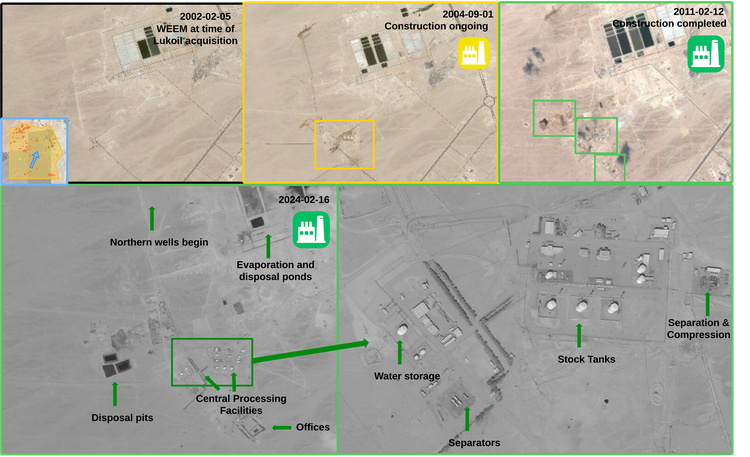

West Esh El-Mallaha (WEEM) Project: Lukoil Overseas & Egyptian General Petroleum Company

Imagery analysis reveals that the WEEM project in eastern Egypt, a joint venture between Lukoil and Egyptian General Petroleum Company (EGPC), is in Phase 3, Production, and is on schedule as of February 2024. This section explains these findings by comparing corporate reports to imagery in four steps: well activity, processing facility activity, phase classification, and schedule classification.

Location, Description, & Context

The WEEM project, located eight kilometers east of Hurghada in Egypt's Eastern Desert, is a significant investment by Lukoil in the region’s oil sector. Lukoil is the only Russian firm involved in onshore projects in the country and has led rapid field development and increased production by 12-fold at WEEM, according to Neftegaz and Rigzone articles.

Lukoil reports that it acquired WEEM in 2002, securing a 50% stake and operatorship under a joint venture with the EGPC. While WEEM has been in the production phase since 1997, Lukoil conducted simultaneous development operations from 2002-2009, building a central processing facility and pipelines. In 2023, Lukoil extended the 25-year production agreement by another five years.

Key Findings

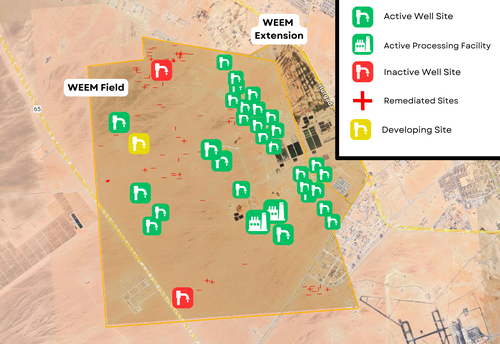

Imagery shows that as of February 2024, WEEM contains approximately 30 active wells, one developing well site, and two active processing facilities (See Figure 5.1.1).

Thirty (30) wells at WEEM are currently active with imagery showing the presence of necessary extraction components as well as pumpjacks, explained earlier to be used when well pressure declines after a period of extraction (See Figure 5.1.2).

Imagery further suggests that these wells were drilled and completed in the first 10 years of the joint venture (See Figure 5.1.3), mirroring Neftegaz reports of Lukoil's rapid development operations to boost ongoing production in the first years of the contract.

There are two active well sites in the WEEM extension, which spans 4.8 kilometers along WEEM’s northeastern border. According to Lukoil reports, after joining the WEEM extension in 2009, the firm drilled two wells by 2014 and imagery similarly indicates drilling in 2009 and completion in 2011 of two wells (See Figure 5.1.4).

Two-thirds of a kilometer (0.7) east of WEEM extension wells and in the center of the contract area, there are two connected processing facilities with oil and gas processing capacity that underwent initial construction in 2002 and harbored key infrastructure by 2004, with marginal developments like the addition of neighboring offices being completed by 2011 (See Figure 5.1.5). The observed development timelines and infrastructure align with Lukoil reports of constructing a centralized processing facility in the first years of the contract.

Overall, these findings indicate that WEEM and its extension are in Phase 3, Production, due to the long-standing active well infrastructure and significant processing infrastructure having been installed by 2011. Moreover, the presence of pumpjacks at most wells indicates declining pressure in the well, which is characteristic of the production phase as explained. This phase aligns with Neftegaz reports claiming Lukoil joined the project when it had already begun production and further developed its infrastructure to boost production, and thus we judge with confidence that WEEM is on schedule.

Conclusion for Egyptian Projects

Egypt's hydrocarbons sector demonstrates a dynamic and significant role within the global energy landscape. Lukoil’s involvement at WEEM is on schedule and attaining successful production levels, building a strong foundation for future cooperation between Egypt and Lukoil. However, WEEM is significantly advanced in its production term and only guarantees a presence for Lukoil into 2033. Moreover, the country's recent economic challenges under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's regime pose potential risks to the stability and attractiveness of its energy sector to foreign investors, which could hinder ongoing oil and gas production projects like WEEM and future projects still in the early stages, announced by Russian Energy Minister Nikolay Shulginov, such as the Zarubezhneft's exploration project initiated earlier this year.

Conclusion

Geospatial analysis reveals some discrepancies between company reports and observed activities from satellite imagery analysis in two out of five Russian-backed onshore oil and gas projects across Algeria, Libya, and Egypt. In Algeria, imagery of the El-Assel project shows it is unlikely to meet its reported production start date in 2025, and the Block 245-South project is shown to be decommissioned. By contrast, the projects in the two other countries are on schedule. In Libya, imagery of the Area 82 project shows it is in the early exploration phase and progressing on schedule, while the As-Sarah Project has exhibited full-scale production since 2021 with ongoing infill drilling in line with Gazprom reports. In Egypt, the WEEM Project is also in the production phase with 24 active wells as indicated by reports.

The findings indicate that Russian energy firms have the highest potential influence on energy dynamics in Libya and Egypt due to their strategic investments and operational progress. The Russian-backed projects with delays in Algeria, on the other hand, could hinder future cooperation in Algeria’s energy sector. According to a Kommersant article discussing 245-South's cancellation, the project represents the wider trend of Russian firms investing in unprofitable ventures as a political lever of the Russian Federation. Rosneft's reported disputes with Sonatrach and exit from Algeria show that these partnerships can cause friction with the host country. However, these findings do not mean that the Russian presence is guaranteed to dwindle in Algeria’s energy sector, especially as its global energy influence increases post-Ukraine. Algeria has signed several hydrocarbon production agreements with Russian firms in recent years, including MoUs with Zarubezhneft and Lukoil in 2020. Russian firms have also made strides to cement their presence in Algeria beyond their ongoing projects, such as Gazprom establishing a regional office in Algeria in 2008. At any rate, these five projects represent a group of Russian investments from the 2000s that granted Russian firms over two decades of ownership and on-the-ground operatorship, which we believe represents a sufficient cross-section of Russian activity in North African oil and gas markets.

Contributors

This article benefitted from the contributions of a team of six undergraduate and graduate Yale students; Dasha Maliauskaya, Elijah Boles, Tetiana Kotelnykova, Stevan Kamatovic, Braeden Cullen, and Aidan Stretch.

May 28, 2023

Tatneft makes oil discovery in Libya at Area 82-4.

The Libyan NOC’s Media office announces a new oil discovery in Tatneft’s contract area 04/82 located in the Ghadames Basin of Libya, quoting Tatneft’s Deputy CEO Nurislam Syubaev. This well, drilled to a depth of 8,500 feet, produced oil at a flow rate of 1,870 barrels per day.Mar 01, 2022

ALNAFT approves Gazprom-Sonatrach development plans at El-Assel in Algeria.

ALNAFT approves Gazprom-Sonatrach field development plans at El-Assel for Rhourde Sayah (RSH) and Rhourde Sayah Nord (RSHN) fields, including gas and LPG midstream processing plants. Production of gas is scheduled to start in 2025.Oct 15, 2021

Tatneft resumes operations in Libya at Area 82-4.

Tatneft returns to Libya with a focus on restarting geological exploration in area 82-4, with reference to signs of Libyan political normalization emerging in 2021. In March, Tatneft signs four production sharing agreements with Libya's NOC, signaling renewed confidence in the region's stability. Tatneft reports their goal to produce 1 million barrels of oil by the end of 2021 and tapping into the potential to extract over 50 million tons of oil from its projects in Libya and Syria.Jan 01, 2016

Production resumes in Libya's As-Sarah project as reported by Gazprom International.

Feb 01, 2011

Suspension of oil project operations due to the onset of the Libyan civil war.

In the months that followed, this suspended the operations of Gazprom International at the As-Sarah (C96 and C97) project as well as Tatneft at the Area 82-4 project.Aug 01, 2009

Tatneft makes a new oil discovery in Area 82 of the Ghadames basin in Libya at the A1-82/04 discovery well.

The A1-82/04 discovery well tested a flow rate of 400 barrels per day from the Ouan Kasa formation at a depth between 5,900 and 5,908 feet.Dec 01, 2008

Gazprom International is awarded the El-Assel contract in the first Exploration & Production (E&P) tender conducted by ALNAFT in Algeria.

Gazprom International was assigned operatorship in blocks 236b, 404a and 405b, and a 49% interest with the remaining 51% belonging to Sonatrach.Jan 01, 2007

Gazprom International gains 49% stake in Wintershall AG's C96 and C97 concessions in Libya's Sirte basin.

Gazprom International becomes the second shareholder of the joint venture Wintershall AG (WIAG) at the As-Sarah project in Libya with a 49% participation interest under two production agreements with Libya's NOC, also gaining operatorship in concessions 91 (formerly C96) and 107 (formerly C97).May 01, 2005

Tatneft signs a 30-year production agreement with Libya's National Oil Corporation (NOC) for concession Area 82-4 in Libya's Ghadames basin.

Tatneft signs a 30-year production agreement with Libya's NOC to explore and develop concession area 82-4 in the Ghadames basin under the 4th Exploration and Production Sharing Agreement (EPSA IV). Tatneft also establishes a local branch in Libya, marking its entry as the first Russian oil company in the country.Mar 24, 2001

Rosneft-Stroytransgaz signs contract with Sonatrach for development of the 245-South Block in Algeria.

Rosneft-Stroytransgaz was awarded the 245-South Block contract in the first international Exploration & Production (E&P) tender in Algeria. They were assigned operatorship at the Gara Tesselit area with 60% interest with the remaining 40% belonging to Sonatrach.

Look Ahead

Overall, Russia's continued involvement in North Africa's energy sector is a strategic move to secure influence amidst the shifting geopolitical landscape and European efforts to reduce dependency on Russian energy. While these five projects do not exhibit a direct correlation with Russian re-positioning in the wake of Ukraine, the renewal of these cooperative ventures as well as new agreements of this type should be monitored in context. Future energy cooperation between North African nations and Russian companies will likely partially shape regional energy dynamics and thus impact global energy markets and geopolitical alignments.

Things to Watch

- Watch for new contract announcements

About The Authors

Undergraduate student, Yale University

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.