Overview

The 2020 Belgian Blue Deal is the nation's ambitious solution to the growing issue of water scarcity. Since its inception, a pattern has emerged, indicating that the government has mostly been able to complete low-cost and moderate-impact projects with either private companies or local municipalities. Therefore, the long-term efficacy of the Belgian Blue Deal cannot be assessed at this time but the start-up phase has been fairly successful.

Our work is primarily a survey of the Blue New Deal to date, not a comprehensive imagery analysis of 200-plus projects.

Activity

The Belgian Blue Deal is an ambitious program that aims to tackle water scarcity and drought through a multifaceted approach. The Blue Deal evolved from Belgium experiencing rainfall in more sporadic and often intense bouts that were not properly absorbed into the ground from 2000 onward, leading to water shortages in some areas and intense localized flooding in other parts of the nation. The program focuses on developing solutions by partnering with commercial, civic, and government organizations to conserve water and limit usage. The projects encompassed by the Blue Deal include research and development, educational awareness, regulations, and structural investments.

Methodology

The methodology for this project was crafted using a two-phase approach. In the first phase, each category of Blue Deal projects was evaluated for its measurability based on the proposed timeline and visible changes that can be viewed from commercial satellite imagery. Out of the 323 total projects promoted by the Blue Deal, 265 were classified as “Investment on Site.” Only these projects, currently the only type with imagery observables were selected for closer inspection. For this project, measurability was evaluated on the proposed project timeline, its ability to be located, and visual changes of progress or lack of progress on imagery. The other categories, focused on legislative measures, funding studies for agricultural innovation, and improving community outreach about environmental education, were excluded due to their lack of activity measurability on imagery.

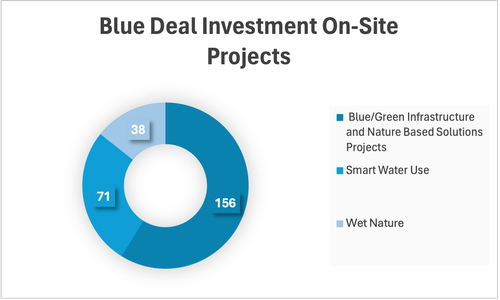

The Blue Deal further divided the 265 available projects into “thematic” categories. These three thematic categories are “smart water use,” “wet nature,” and “blue-green infrastructure and nature-based solutions.” The figure below shows the number of these thematic projects under the “investment on-site” classification. The 265 total projects are broken down into categories thusly:

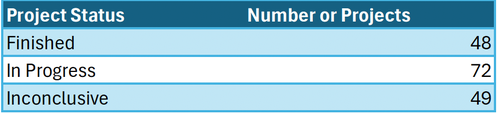

Since its inception in 2020, the Belgian Blue Deal has been a primarily aspirational effort with highly specific reporting details often lacking. Therefore, a reasonable population size had to be determined to gauge status, progress, or delay. After removing duplicates and projects with unclear timelines and details, there were 169 unique projects in the investment onsite category. After determining this number, each project was geolocated down to the most accurate available level. Ideally, this involved determining specific coordinates and confirming the location on imagery. If specific geo-coordinates were not available, we identified the next administrative level such as a town, park, or region mentioned in the plan, followed by confirming the general location on imagery. Thus, the term geolocated is used to indicate confirmed coordinates for the project or a localized region that could be examined on imagery. Further analysis was then done to find the current status of each project:

After calculating these figures, 120 projects in the finished and in-progress categories were eligible for further analysis. Exemplar projects were selected from each thematic category for closer analysis and expanded writing; the selected exemplar projects represent approximately 10% of each project theme. Imagery analysis of these exemplar projects helped us break down the projects into construction phases to show current progress and to estimate projected completion timelines.

We curated excelBlue Deal Master Databasestructured tabular data and kmlBelgian Blue Deal 2024locational data documenting location, project type, and a light assessment of status for 169 projects, so future researchers can build upon this foundation to assess impact. How the "light assessments" in the "Assessment" column were formulated is essential for readers to understand. We wanted to highlight the distinction between aggregated secondary text reporting and quick primary source imagery scans from Google Earth in the structured data.

In the structured and locational data some of the in-progress, finished, and inconclusive judgments were sourced from websites such as the Riviercontract Vilet-Molenbeek (river contract website) and a sub-page on the official Blue Deal project website such as the one for the "Wet Nature Kelderijbeemd in Bornem Project."

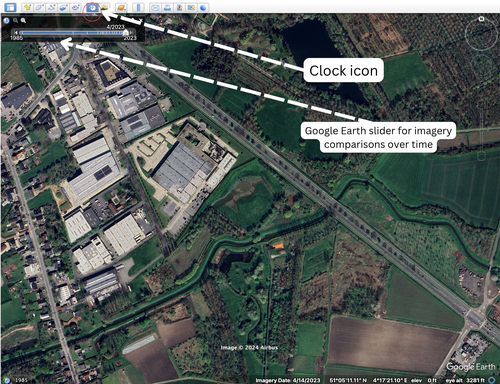

The textual analysis was supplemented with quick imagery scans derived from the historical slider feature in Google Earth. There were typically 2-5 image skins dated from 2020 to the present that facilitated a quick analysis of the targets to include simple geolocation as a by-product.

The image above highlights the use of the Google Earth slider that was applied to a portion of projects for the "light assessments" in the excelBlue Deal Master DatabaseAssessment column and kmlBelgian Blue Deal 2024KMZ annotation bubbles.

When interacting with the structured and locational data for this project, a firm understanding of how these "light assessments" were made is important; especially when differentiating between the "light" assessments provided in the structured and locational data and the more detailed analysis of the exemplar projects below.

Smart Water Use

All 72 smart water use projects were successfully geolocated, and 30 had imagery signatures and markers to analyze. Six projects in urban and rural settings with varying geographic features were selected for further analysis. Projects in this category primarily focused on improving the efficiency of existing water use models through water recycling and limiting industrial water use.

Incentives from the national government play a large role in this category. All of these projects follow a similar pattern of a private commercial or industrial venture receiving a subsidy from the federal government to encourage them to include green elements in upgrades during renovations or expansions. This government funding incentive program has proved to be fairly effective in helping ensure more efficient water use in the industrial sector, but the projects tend to be small in scope, limiting how much water they conserve. While these projects are often small in scope, the large number of them could help the Blue Deal meet some of its goals even if modestly.

Tiense Sugar Refinery

The Tiense Sugar Refinery is a private-public partnership that received a 1-million-euro subsidy from the Belgian government through the support of the Blue Deal to start a 25-million-euro construction project for a new diffusion tower. The precise date of the Flemish government cash infusion is unknown. Government officials were present at the inauguration ceremony in March 2023. We estimate the cash infusion took place in 2020 or 2021. The new diffusion tower is listed on the official Blue Deal project page along with the announcement of the subsidy received by the sugar company to complete this project. The company's description of the project states that the new diffusion tower will save 150,000 cubic meters of water annually, reduce energy consumption by 25%, and lower CO2 emissions in three ways. First, the tower's design allows for the processing of more sugar beets with less water due to its increased volume over the older horizontal diffusion drums. Second, the project includes energy-efficient boilers to lessen the water needed for steam production. Third, the new tower introduced a closed-loop system to recycle as much water as possible. While this is a minor amount of water saved compared to the estimated 780 million cubic meters of water Belgium uses per year, these small projects represent a step in the right direction when combined across the broader Blue Deal plan. No firm timeline was provided on the official Blue Deal website nor the Tiense Sugar Refinery website; however, given that the Belgian Blue Deal officially began in 2020, it can be estimated that the diffusion tower project started in approximately late 2021 or early 2022.

In September 2019, the original factory had room for further refinery expansion and the future site of the diffusion tower can be seen (Figure 1).

In August 2020, no visual changes were identified (Figure 2).

In May 2023, the diffusion tower appeared to be complete.

Albert Canal Hydroelectric Pumping Stations

While government incentives are mostly helping secure commercial support for smaller green projects, the Belgian government is also assisting with larger projects designed to save 937 million cubic meters of water, while also providing renewable electricity for Belgium's power grid. These projects involve constructing new efficient pumping stations with hydroelectric generators at lock complexes on major waterways.

The ongoing construction of six hydroelectric pumping stations near the locking complexes on the Albert Canal is part of Belgium’s Blue Deal (and listed on the Blue Deal website) in its effort to prevent water scarcity and drought by strengthening the water system and tackling water use. Once all six stations are complete, they are projected to cut the amount of water pumped into the locks for shipping purposes by approximately half. In addition, these six stations will help provide electricity to at least 3,000 families. These pumping stations align with the Blue Deal's dual-purpose plan of developing structural solutions that strive to retain water locally wherever possible, use less water, reuse more water, and tackle wasteful consumption. We measured the progress of these six pumping stations to provide context and assess parts of Blue Deal impact.

Four of the six proposed stations have been completed, while the other two (situated in Genk and Wijnegem) are in the planning and construction phases with the Genk lock kicking off in 2023, followed by Wijnegem in 2025, according to Flanders-based websites reporting on the pumping stations. Beyond these initial start dates, official project timelines or masterplans were not found online by our team. For our analysis of these projects, four visually identifiable "phases" were noted, and used as supplementary timelines since comprehensive timelines were not found online. These pumping stations follow four phases that can be measured for progression.

Phase One is the planning phase where a suitable site is chosen for the pumping stations. This image of the Diepenbeek locks (Figure 4) shows how each of the projects starts with an unimproved area with the correct dimensions for a pumping station. The Figure 4 image from September 2019 shows Diepenbeek before clearing or construction. The outlined spot highlights the area that will be cleared for the station.

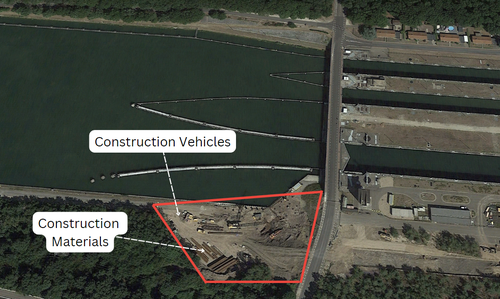

In Phase Two, the identified land is cleared in preparation for the construction of the pumping facilities. In this image from August 2020 (Figure 5), trees were removed, the land was leveled, and construction vehicles and materials were present.

Phase Three represents the construction of the pumping station. In this image from February 2021 (Figure 6), the pumping station is in the process of installation as signified by the construction activity and frame of the building in the image. However, the Archimedes screws, the piece of equipment that physically pumps the water, have yet to be installed, indicating it is still early in the construction process. Relating to activity at Diepenbeek specifically, this image coincides with the installation company EQUANS's statement that they had been active on the site since February 2021.

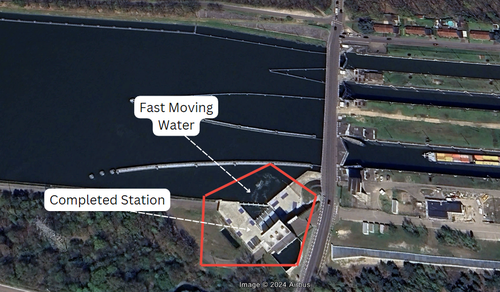

Finally, Phase Four is when the project is completed and operational. In this image from April 2023 (Figure 7), the Diepenbeek pumping station is complete and operational as evidenced by the completed building, removal of construction equipment, and grass has started growing in the areas where the vehicles and materials had previously been staged. Additionally, signs of fast-moving water currents near the pump indicate that the pumping station is taking in water. With the Diepenbeek site as a case study, from its initial land clearing before August 2020 to completion of the station in October 2021 (with the pump itself not starting until January 2022), it is estimated to take a year and a half to complete one of these pumping stations.

Considering these four phases, the progress at the latest site in Genk can be compared to other completed pumping stations to determine if it is on pace to be completed within planned timelines.

The Figure 8 image shows a construction crane and land disturbance at the site indicating Phase Two preparation. This coincides with an article from a November 2023 local Flemish newspaper indicating that "the construction of the hydroelectric power station at a lock-in Genk-Zuid has started.” From the image and article, the pumping station at Genk was likely in Phase Two by February 2024, and reports from June 2024 project that the Genk lock will be complete by Summer 2025.

Borgloon Sorting Shed and Water Basin

In the summer of 2021, fruit and vegetable company BelOrta announced they would be constructing a "state-of-the-art sorting warehouse for apples and pears." This fruit warehouse is a private venture of BelOrta. Also happening concurrently and with encouragement and approval from the city of Borgloon, BelOrta is also supporting a “water basin” that collects rainwater runoff from the existing BelOrta buildings and pavement. The basin is listed on the Blue Deal project page and is also part of the larger "Collective Rainwater Projects" of the Blue Deal. Projects that are part of the collective rainwater projects groups aim to improve the rainwater regional catchment abilities. For this specific basin, the regional government allocated approximately “200,000 Euros." Construction of the buffer basin, finished in mid-June of 2023, can hold approximately “488,000 Liters” of water, allowing local farmers to utilize pesticide-free water. According to the Flemish Minister of the Environment, the basin will, “save a massive amount of water that they would otherwise have to pump from either local waterways or the ground.” This basin helps the local community with its farming needs by saving approximately “2,500 meters cubed (250,000 liters) per year."

The following images show the progression and features of this project from pre-construction to completion.

Figure 9 shows the outlined area where the basin will be constructed. The land around the proposed area was flattened for expansion.

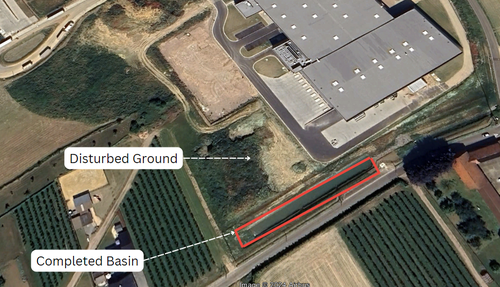

In the next image (Figure 10), the basin and the sorting shed have been constructed. Near the basin itself, disturbed ground can be seen, which indicates the presence of construction vehicles and equipment that would have been used to dig the basin and help with the construction of the sorting facility.

Deeper Blue: Underground Basin

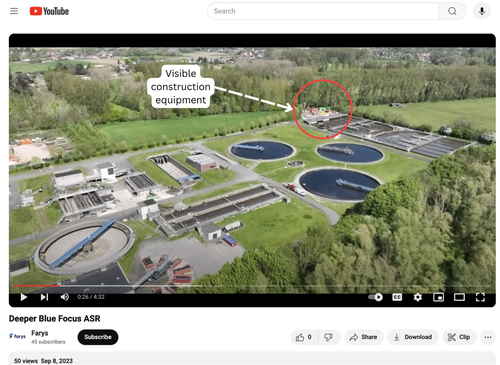

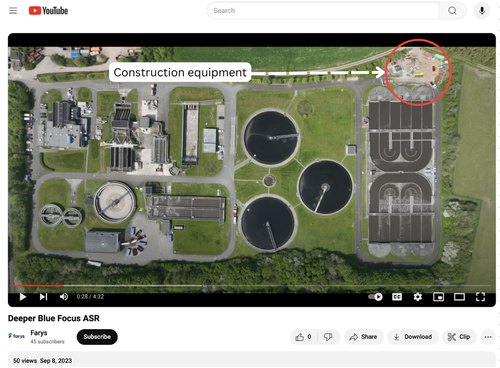

The Flemish city of Aalst sewage treatment plant aims to reuse purified wastewater as a source of drinking water. The Deeper Blue project is officially listed on the Blue Deal Project page and is part of the larger "Reuse of Effluent" project group under the Blue Deal which aims to process wastewater into drinking water. Specifically this project envisions testing whether cracks and crevices deep within the earth can be used to store excess water during the wet season to draw upon to offset shortages in the dry season. In the late spring of 2023, the Farys company announced they were selected to drill a more than 200-meter well at the water treatment site. This project is designed more as a proof of concept, as Farys is testing to see if upon extraction the stored water will still be potable. If the water remains potable after its extraction, the basin is estimated to hold up to “100 million liters" of water, which could support 3,000 families during droughts. Additionally, upon the success of the Deeper Blue Basin, the project could be similarly replicated in other parts of Belgium.

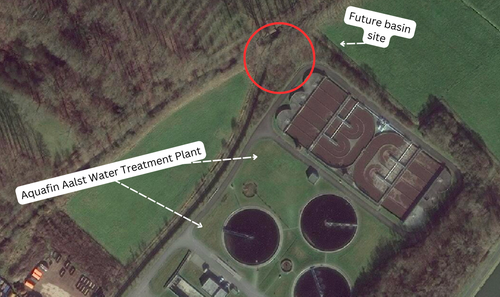

In the image from March 2023 (Figure 11), the outlined circle represents the proposed drilling site for the underground water storage.

In the next image from May 2023 (Figure 12), drilling preparation had begun, which is evidenced by the cleared foliage and construction materials at the project site. This is supported by an announcement that work on the project was scheduled from “April 11 to July 7” 2023.

In the images (Figures 13-13a) from a YouTube video discussing the Deeper Blue project by Farys, construction and drilling equipment can be seen in the same area that was assessed to be the zone for the underground basin. These video stills illustrate that construction was still ongoing in early September 2023.

In the last image, dated September 2023 (Figure 14), all of the construction and drilling equipment has been removed from the site. The ground shows signs of disturbance consistent with drilling, as evidenced by the white patch on the basin site (Figure 14). As of September 2023, the underground buffer was completed on time based on visual observation and official media about the project. This is reinforced by an announcement on the VRT News website announcing the successful completion of the project on July 25, 2023.

If the extracted water is still potable, the Deeper Blue project will be a strategic underground reserve of water that can service approximately 3,000 families during the dry season Furthermore, the success of this project means that it could be replicated in other regions of the country to augment overall reserves of drinking water.

Circular Water Use: Tech Lane Ghent Science Park, Campus Ardoyen

Circular Water Use: Tech Lane Ghent Science Park, Campus Ardoyen

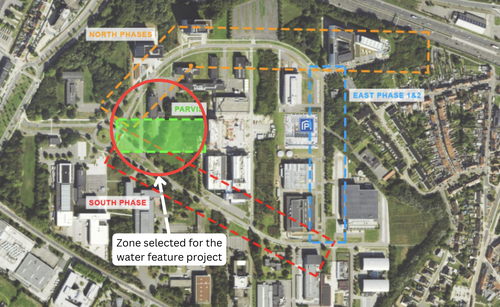

In East Flanders, at the University of Ghent, the school is tackling water management on the Ardoyen campus. The circular water use project at the Tech Lane Science Park at the University of Ghent Ardoyen is a project affiliated with the Blue Deal through its listing on the official project website and its greater affiliation with the larger project group "drought testing grounds." This larger project group is a coalition of Blue Deal efforts that increase rainwater collection and circulation to improve water scarcity conditions during drought. Specifically, the campus is taking a multi-phase approach for this initiative, ranging from upgrading underground pipelines to the "centerpiece" project, which is a central water feature on the campus that will be connected to the greater underground infiltration system to improve the circular water system. The University website states that the phase of the project that concerns itself with the construction of this water feature had a timeline of December 2022 to Fall 2023.

This image (Figure 15), originally posted on the Ghent Tech Lane website, highlights all the areas on the campus where water feature work and underground pipelines were to be installed.

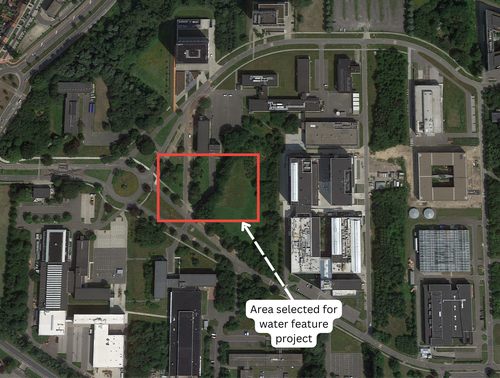

The area zoned for this water feature project can be identified in July 2021 (Figure 16), a year before the start of the project.

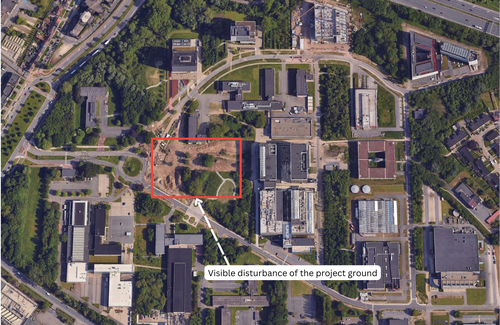

By May 2023 (Figure 17), topsoil removal and preparations for digging at the site are evident. Digging for the main water feature appears in the lower left-hand portion of the project area. Thus, it is likely the water feature project began at this stage but is still in the early phases of the project.

Instagram images from an architectural site on the project indicate it was completed by March 2024 (Figures 18-18a).

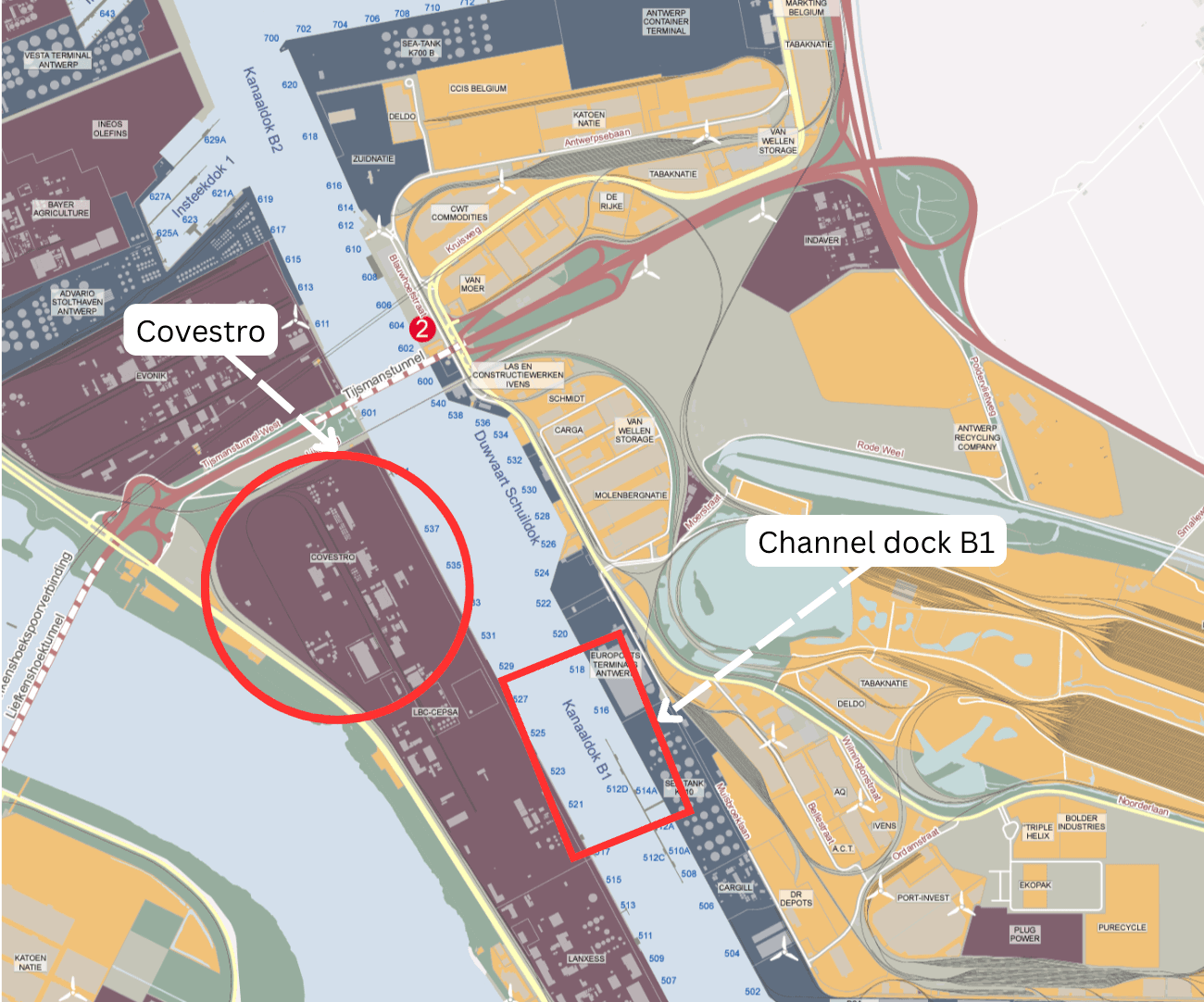

Covestro Demineralization Facility

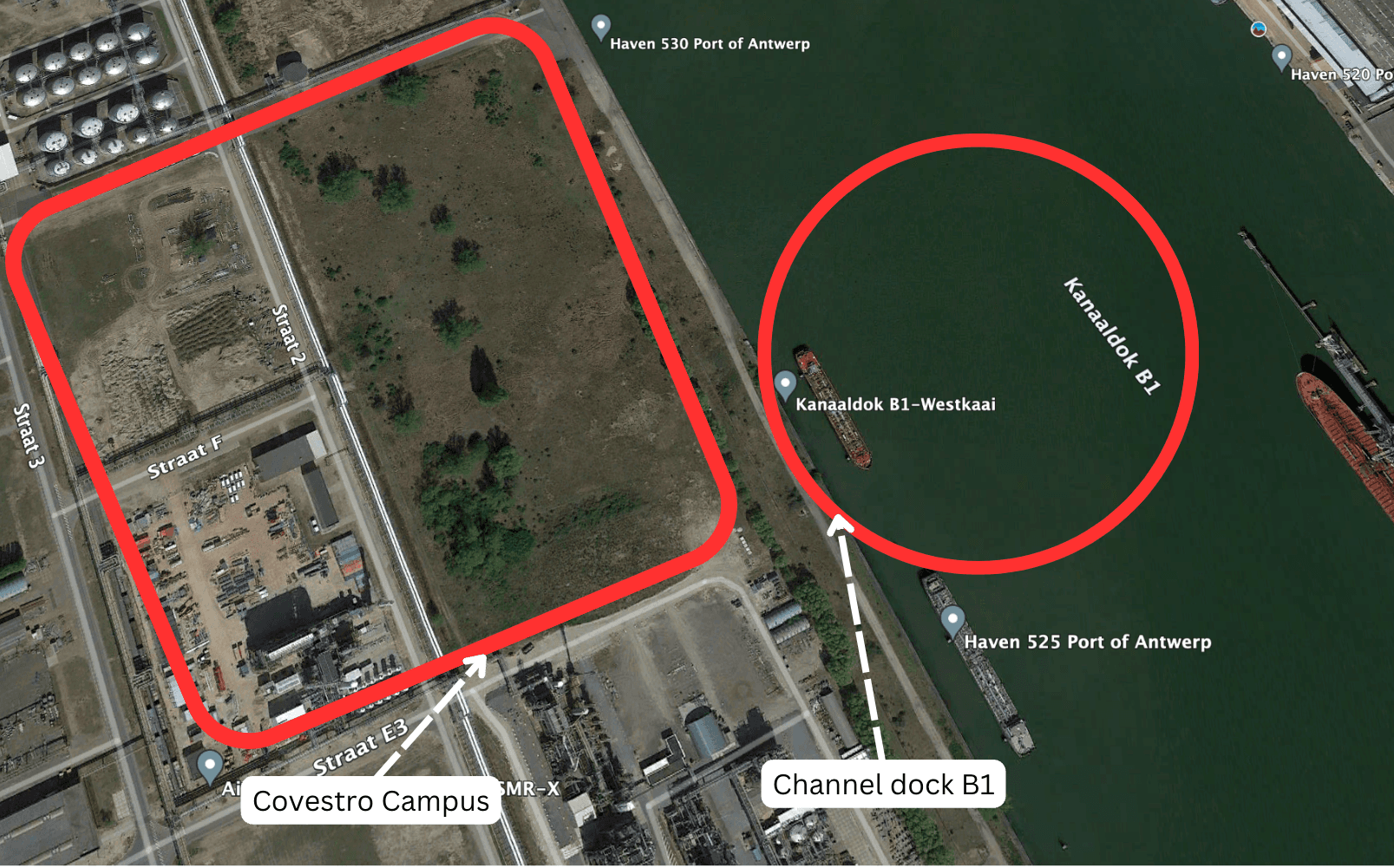

According to an article from December 2020 in the online industrial journal WaterWorld which reports on industries instituting green changes, chemical company Covestro undertook an expansion project at its high-grade plastic production facility in Antwerp to install new water desalination and demineralization facilities which is listed on the official Blue Deal project page. Convestro's production of advanced polymer plastics at the facility uses millions of liters of water per year. As part of the company's efforts to reduce its strain on the drinking water supply, it is building a water treatment facility in part with chemical company Evonik and investment company AVAIO Capital. The desalination and demineralization process involves using a filtration system and large container tanks to chemically ionize the water to remove contaminants which will turn the brackish dock water into a usable raw material for the chemical factories, significantly cutting down industrial water consumption. According to an AVAIO Capital news release, the desalination facility will be built on the Covestro campus and a pipeline will deliver water to the neighboring Evonik factory.

An AVAIO Capital news release stated that the new facility will convert water from the B1 Channel Dock in Antwerp. Below, the official map of the Port of Antwerp and commercial satellite imagery (Figure 19) confirmed this claim and corroborated the location of the water facility project on the Covestro campus.

Imagery from April 2020 shows the locations for the new demineralization facilities (Figure 20).

By July 2021, these sites had been cleared and were in preparation for the start of construction (Figure 21).

The project moved ahead with more clearing work as noted in an image from March 2022 (Figure 22)

By April of 2023, filtration ponds were visible in the western portion of the project area, as well as the construction of the new demineralization facility (Figure 23).

In January 2024, the project progressed with new construction south of the originally identified facility construction, which could eventually house the pumps and filters necessary to purify the dock water. (Figure 24). This construction conforms to the WaterWorld article's statement that the project was planned for completion in late 2024.

Smart Water Use Conclusion

Of the 30 measurable projects, the six analyzed would indicate that this thematic category in the larger "Investment on Site" classification improves the efficiency of existing water systems or enhances existing infrastructure.

Wet Nature Projects

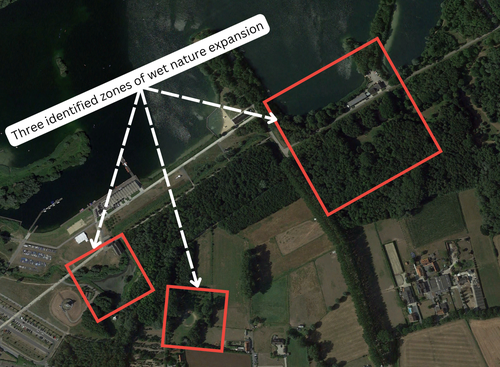

Within the wet nature projects category, all 38 projects were geolocated. Of these 38 projects, 22 projects had observable activity for further analysis. We researched and analyzed two exemplar projects to highlight this category type. These projects are all in rural settings, focusing on restoring natural areas to help with flood control and water conservation by improving natural water catchment areas, restoring wetlands, and improving recreational areas.

Expansion of the De Gavers Provincial Domain in Harelbeke

The expansion of the De Gavers provincial domain in Harelbeke is a wet nature project affiliated with the Blue Deal by being directly listed on the main project page and through its direct affiliation with the "Local Leverage Projects for Wet Nature" which highlights its Blue Deal association through the use of the project logo on the website. The project intends to create three types of sub-zones, allowing for more water infiltration in the area. The project goals are varied, ranging from creating wet lakes, meadows, ponds, canals, swamp forests, forest edges, shrubs, and rows of trees so the lake landscape can act like a sponge and retain water. The project also contains plans for a controlled flood area, the expansion of the nature reserve, and the return of the Gaverbeek River to its natural winding course. According to the official website for the Province of West Flanders:

With a re-meandering, we restore the original structure of a watercourse. For fear of flooding, watercourses used to be straightened, so that water drains faster. By digging out meanders now and connecting them to the watercourse, not only does the chance of flooding decrease, but water also gets more space. This makes the watercourse more resistant to long periods of drought. For the Gaverbeek, we are creating 130 meters of extra space for water.

The progress of this project can be seen in the images below.

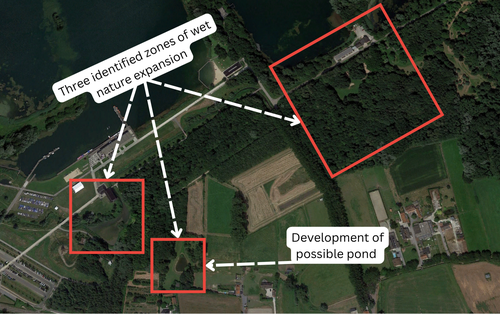

The plan for the De Gavers provincial domain identified three areas for green improvements (Figure 25). As of July 2020, there were no indications of new bodies of water or changes in landscapes, indicating the project had not yet started.

By July 2021, the construction of a small pond was observable (Figure 26), indicating that the project had started between September 2019 and July 2021.

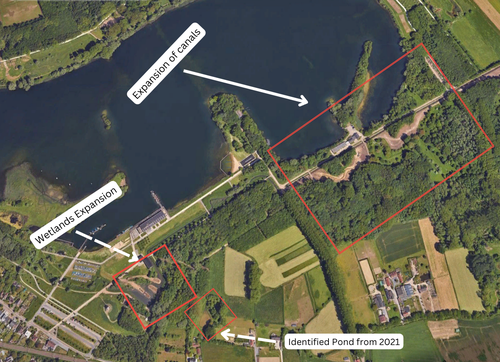

By May 2023, the project had expanded to include the introduction of new wetlands and the expansion of a new canal (Figure 27) on the project site.

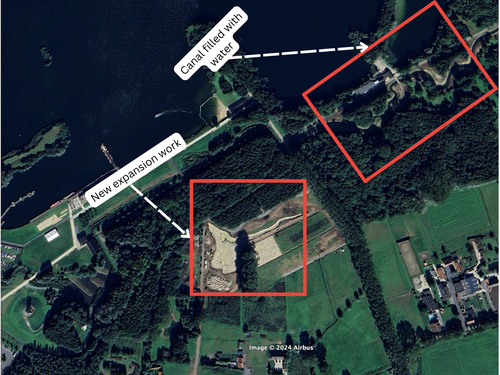

Work at the site continued from May to September 2023 (Figure 28) with the completion of the canals and the start of additional work at the site.

Redevelopment of the Babbelbeekse Beemden Valley in Duffel

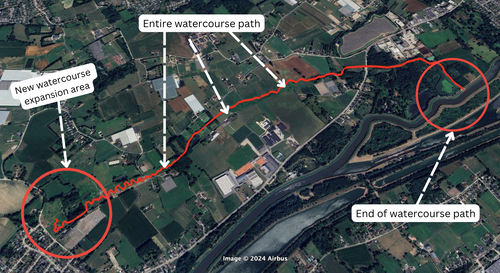

The redevelopment of Babbelbeekse Beemden Valley in Duffel is a wet nature project; like many in this thematic category, it shares an association with the Blue Deal by being listed on the main project page and through its larger affiliation with the Local Leverage Projects Wet Nature project group, which is a large group of projects associated with the Blue Deal. This project focuses on restoring the natural structure of watercourses and employs various interventions to retain and store water, including constructing sloping banks and digging meanders to return a natural curving shape to the Arkelloop River (See meandering explainer above).

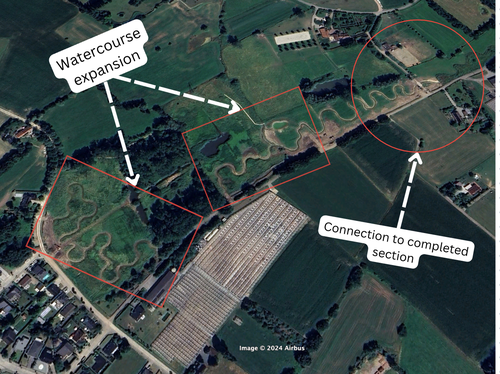

A baseline image from May 2021 (Figure 29) shows the general area of the watercourse expansion work. The image also shows early meandering work, indicating the project started along planned timelines.

By March 2022 (Figure 30), work at the site had started with the restoration of a small watercourse narrow trench.

This watercourse was expanded throughout 2022 and early 2023. By March 2023 (Figure 31), the watercourse expanded to create a larger wetlands area through meanders as water flowed towards the main river.

By July 2023 (Figure 32), the project appeared nearly complete with a watercourse winding to the larger Arkelloop River allowing rainfall to better seep into ground aquifers as it slowly drains towards the river.

Wet Nature Conclusion

Of the 22 measurable projects, the two exemplars analyzed indicate this thematic category partially helps with flood control and water conservation connected to Blue Deal goals.

Blue-Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions

Of the 56 blue-green infrastructure and nature-based solutions projects in the Blue Deal, we were able to geolocate all 56. We analyzed and expanded writing on five projects that ranged from rural, urban, and coastal areas. These projects share a common thread in that they were often linked to already planned civil-industrial-governmental partnerships where green improvements like water catchment areas and limiting rainfall loss were added to planned upgrades to recreational areas for Belgium's population. They often represent smaller-scale projects in terms of water savings but have a potential impact in garnering further public support.

Cleaning up the Dender Lanscape:

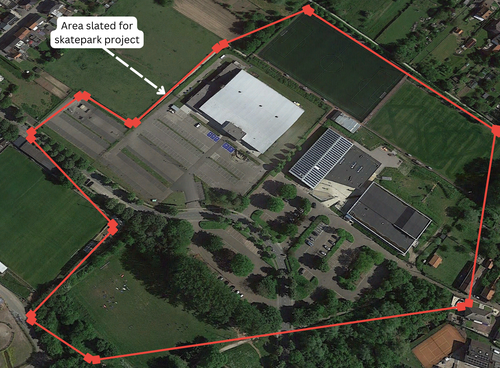

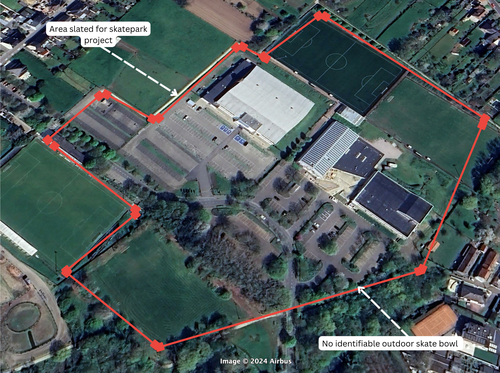

Waterskate Park Sports Site, Liedekerke

The cleaning up of the Dender Landscape is an area project coalition affiliated with the Blue Deal through its listing on the Blue Deal website. The projects associated with this project coalition aim to redesign public spaces to make water a central facet of the space. The Sports Site in Liedekerke is an example of a civic project adding green elements to meet the goals of the Blue Deal. In this case, the project aims to create a skatepark bowl that will also serve as a water catchment site to filter rainwater into reservoirs. Thus, during dry weather, the skatepark would be used by citizens for entertainment, but during heavy rains, it would function as a man-made pond funneling rainwater into the reservoir system. This design for the skatepark seems to be conceptually similar to projects in Denmark and Norway that have designed skate bowls to collect rainwater that will either have drainage or canal systems that lead the water out of the bowls and into larger basins or reservoirs. The project in Belgium was scheduled to start in 2023 with a planned completion date of 2026.

As of May 2021 (Figure 33), the original structures and greenspaces can be seen in the area selected for the skatepark project.

However, as of April 2023 (Figure 34), no outdoor skate bowl similar to other skatepark projects was visible.

Nature Reclamation

Dunes

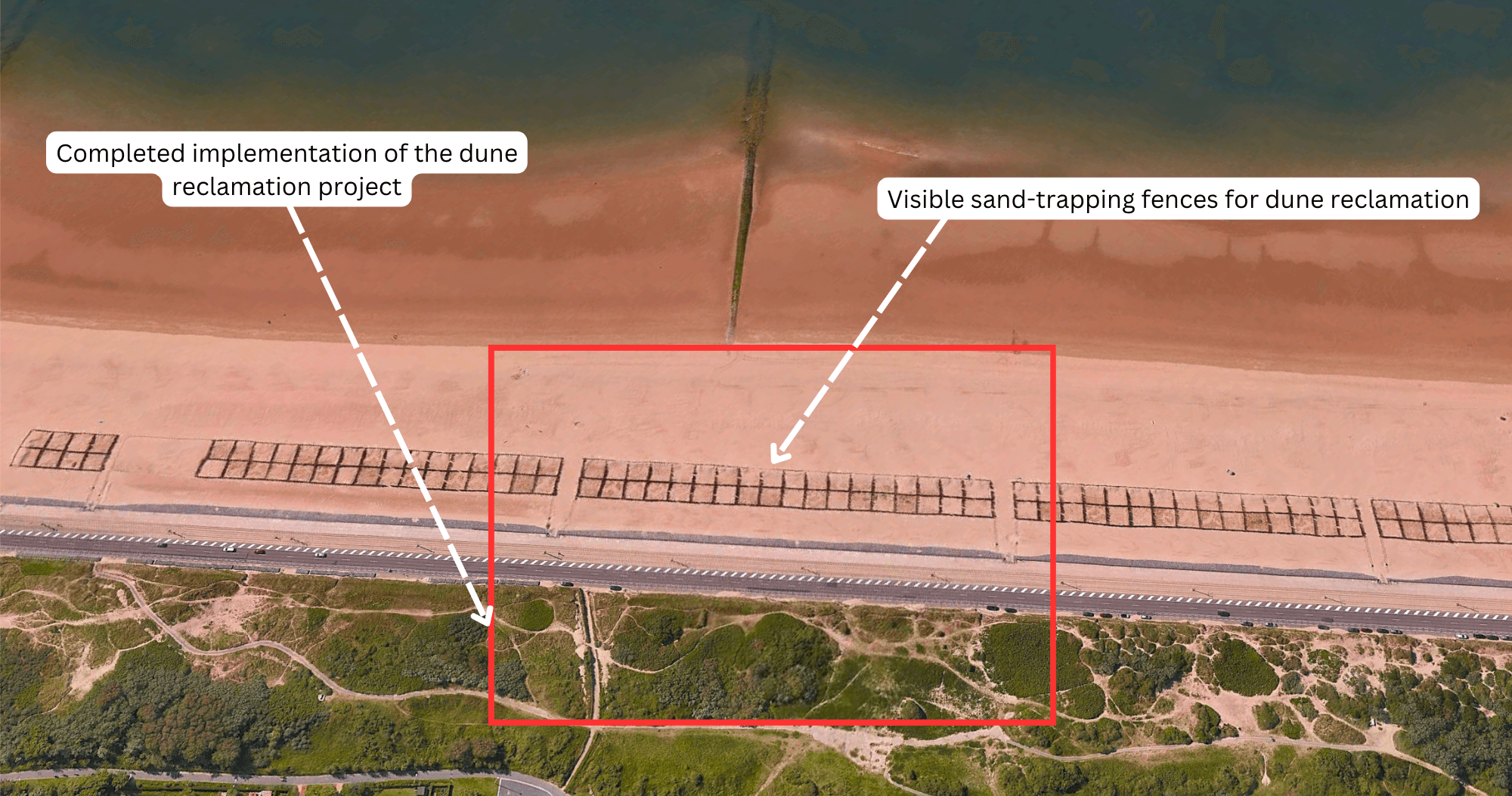

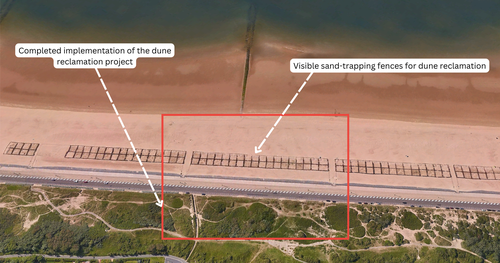

The Raversijde project, listed on the Blue Deal project page, is a subsidiary project of the Dune Complex Flagship Project. The Dune Complex Flagship Project is one of four project coalitions under the Blue Deal umbrella to accelerate the realization of each project's intended solution. The Raversijde project involves rebuilding dunes along the Belgian coast to aid rainfall retention in Ostend in conjunction with updates to a bicycle path along the same stretch of coast. The dune reclamation portion of the project aims to rebuild dunes to stop rainfall runoff into the sea. These reconstructed dunes have a dual effect. First, they reduce coastal erosion, and second, can channel rainwater through ditches and pipes into spongy lands allowing for better groundwater infiltration or channeling.

The two images above (Figure 35-35a) compare the Raversijde project. The first image from July 2020 shows the beach area before the project started, and the second image shows the dune reclamation completed by June 2021. Dune reclamation efforts are visible with the construction of sand-trapping fences, which work to preserve and build dunes by reducing wind speed and directing visitor traffic away from these ecologically sensitive dunes.

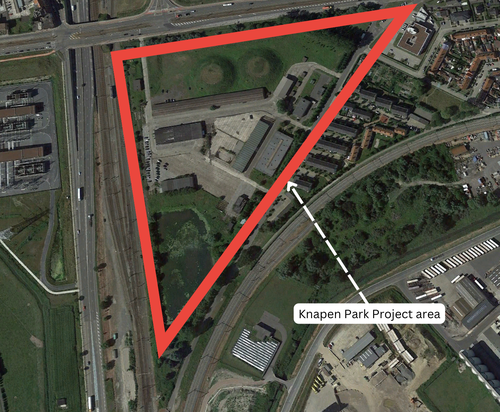

Knapen Park in Zeebrugge

The Knapen Park in Zeebrugge shares a similar involvement with the Blue Deal, like many other projects, by being both listed on the main Blue Deal project page and its affiliation with the Dune Complex Flagship Project. The Dune Complex Flagship Project is one of the four major project groups under the Blue Deal and is listed on the official website. The projects that are part of the Dune Complex Flagship Project are focused on water reuse, nature reclamation, and the softening of terrain to improve absorption. The Knapen Park project represents a similar civil-industrial-governmental project in an urban environment. The project involves turning an abandoned military site near the port for the city of Bruge into an urban park. This project intends to expand green elements such as replacing buildings and pavement with wadis and infiltration moats to allow rainwater to better seep into underground aquifers.

The above map (Figure 36) shows the plan for the project after the removal of former military buildings and cement covering the area. We used this plan to assess progress on this project according to the plan's website.

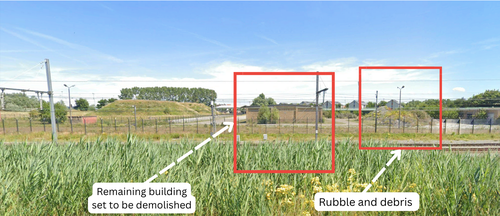

Imagery from July 2020 (Figure 37) shows the area for the planned park. The former military barracks remain, yet other work has not started on the project.

By July 2021 (Figure 38) the demolition phase of the project was not underway and no visible changes were observed.

The ground image from July 2022 (Figure 39) showed that one building had been demolished.

This last image from June 2023 (Figure 40) indicates the demolition of additional buildings and clearing activity. The addition of an athletics court can also be seen in this image. The planned wadis and infiltration moats are not visible. According to the Blue Deal project website, the park is projected to be done by 2024.

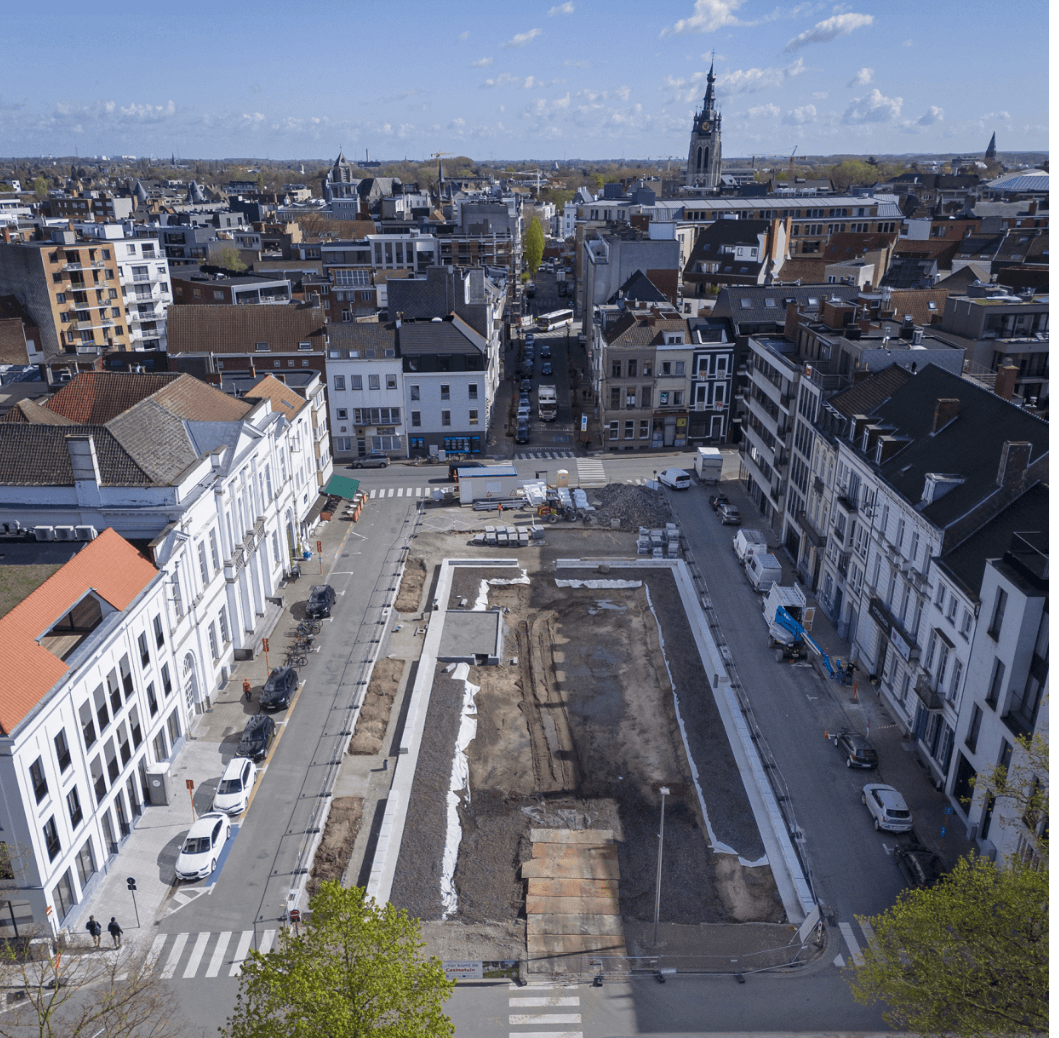

Transformation of Parking Spaces into Green-Blue Living Spaces

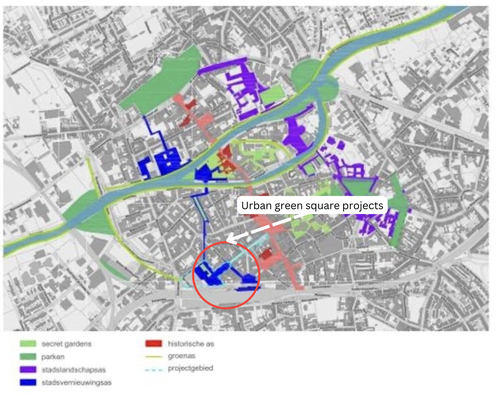

This project involves the redevelopment of the above-ground parking in the western Belgium city of Kortrijk at the Casino and Conservatorium; this project is explicitly listed on the Blue Deal project page and is further affiliated with the larger Green-Blue Interconnection project that has an association with the Blue Deal through the use of the logo on their website. The plan calls for redesigning parking areas into urban green spaces and water collection systems, which will be implemented by softening the existing terrain to increase groundwater infiltration. According to the plan's website, the project will transform roughly 4,000 square meters of parking lots into water-permeable green spaces for public use.

The above map (Figure 41) comes from the Blue Deal plan for this project and identifies areas of the city planned for green urban upgrades. We focused on the areas in dark blue, which are parking lots at the casino and conservatory squares that are scheduled to be turned into urban green-blue town squares.

The images above (Figure 42) on the left and right are official project renderings provided by the city of Kortrijk and illustrate what these green transformation projects will look like when completed.

The Kortrijk Plan's website indicated a project start date of late summer or fall 2023; however, according to media reports, the city broke ground on the projects in January 2024. The image of these lots from May 2023 (Figure 43) illustrates what they looked like before large-scale construction.

The images from April 2024 (figure 44) are official images provided by the city of Kortrijk. Progress on both the Casino and Conservatorium squares is well underway. The project was intended to be complete by April 2024; however, media reports shared that a delay in the shipment of natural stone in early April hindered progress, but as of June 17, 2024 progress has resumed.

Green Blue Transformation Vorselaar: Green-Blue Connection from the Urban Center to the Countryside

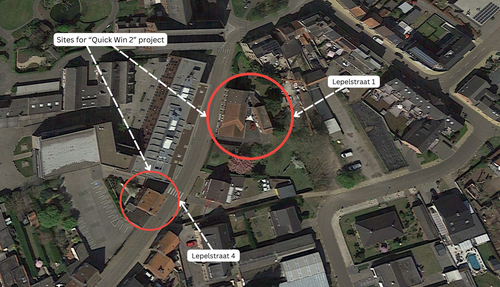

The final project involves the transformation of streets in the city of Vorselaar into green streets. This project is listed on the Blue Deal project page and is further associated with the larger Green-Blue Interconnection project - the Blue Deal logo can be seen on the Green-Blue Interconnection project page. Green streets are water-permeable modifications often by narrowing and green beautification to traditional streets that channel water into underground storage or away to reservoirs for later use. According to the Vorselaar plan, the city will reform all of its 104 streets by 2046, but it will start with 3 "quick win" street projects started in 2022 with a 2.5-year completion schedule. These "quick win" projects are designed to improve rainwater infiltration, storage, and retention capacity. The project that has been selected for further analysis is the"Quick Win 2" project, which focuses on creating green streets to connect the urban center of Vorselaar to the countryside with a dike track running along these paths for water infiltration. Specifically, the street Lepelstraat in the city of Vorselaar will have a pedestrian path and more narrow and "slow roads" with trees to soften the urban space and improve water infiltration. To achieve this new green path while accommodating vehicle traffic, the municipality plans to purchase and demolish 4 Lepelstraat (a house). Furthermore, this quick-win project also wants to pave the private garden behind house 1 Lepelstraat and turn it into a public park effectively creating an interconnected green space on this street.

In 2020 (Figure 45), the existing houses that will be modified or demolished to achieve the "quick win" project were identified. It demonstrates the baseline image from before the project started.

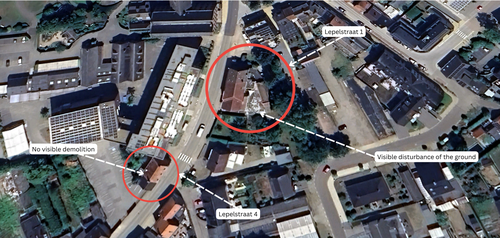

As of May 2023 (Figure 46), the ground image of the garden behind Lepelstraat 1 shows no visual indications of paved park conversion or public availability indicating that the "quick win 2" project has not started.

Finally, in July 2023 (Figure 47), the image for the area showed no demolition of Lepelstraat 4 but visual evidence of ground disturbance in the garden of Lepelstraat 1 indicating the possible start of the "quick win 2" project by mid-2023.

Blue-Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions Conclusion

The 56 measurable projects and the six exemplar projects analyzed indicate that this thematic category will partially assist with water conservation and limiting rainfall loss.

Conclusion

The Belgian Blue Deal is an ambitious program aiming to tackle water scarcity and drought with a multifaceted approach. It contains 323 proposed projects, but the majority of these projects are either aspirational or legislative, leaving only 169 projects with measurable details. After we analyzed these projects, we determined that 48 were completed, 72 were in progress, and 49 did not have enough information to evaluate their status. These numbers highlight both the early stages of the Belgium Blue Deal plan and the aspirational nature of many of its projects. Of the 323 total projects listed as part of the plan, 52% had measurable details. Of these 169 projects with measurable details, 48% were in progress or completed as of 1 April 2024.

Our analysis is twofold: a light analysis of all of the investment on-site projects, which can be found in the kmlBelgian Blue Deal 2024structured data, followed by a more in-depth analysis of the exemplar projects. The representative projects analyzed in this text demonstrate that the Belgium Blue Deal is working on a series of urban and rural projects designed to conserve water, facilitate water reclamation, and control flooding. At this early stage, an overall assessment of the Belgium Blue Deal's success or shortfalls will require more to judge; however, our light assessments and exemplar highlight several trends to judge in context.

Contributor Note

Tearline projects are typically conducted by seniors and graduate students. Ole Miss and Tearline created an opportunity for more junior students, such as freshmen and sophomores, to grow their open GEOINT and OSINT skills. Special thanks to Andrew Kamler (freshman), Tyden Kortman (sophomore), Campbell Holder (sophomore), Grace Wilson (junior), Belle Keebler (junior), and Alexandra Quaadman (senior).

Look Ahead

More time will be needed to determine if the government and partnered industries will be able to meet the estimated timelines for the larger projects as well as the many and varied smaller-scale projects.

Things to Watch

- Compare press releases and declarations against imagery progress indicators

- Use our structured data to continue studying these projects

About The Authors

Undergraduate student at University of Mississippi, Lead Researcher and Author

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.