Overview

Chinese companies control 72% of the cobalt and copper mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a country that produces over 70% of the world's cobalt and approximately 10% of its copper, according to Canadian estimates and foreign relations research councils. [1, 2, 3]

Like many other critical and near-critical minerals—which are minerals or rare earth elements used in “critical” technologies like renewable energy— a large portion of cobalt and copper the West receives originates from Chinese extraction or refinery sites, making these supply chains dangerously insecure.

Activity

This paper aims to understand how Chinese mining companies are solidifying their dominance of the DRC's cobalt and copper supply chains by analyzing the development of three mines: Sicomines, Tenke Fungurume, and Kisanfu. As major producers that have undergone recent transformations, such as physical expansions and increases in vehicles and equipment, these mines can provide insight into current and future trends in the China-DRC mineral relationship and how they impact potential opportunities for the United States to secure critical mineral supply chains. This research uses satellite imagery to reveal that the mines have increased ore production, maximized on-site processing power and capacity, and implemented other tactics to continue scaling up their production and processing capacity.

Background

As the great power competition between the US and China intensifies, attention has increasingly shifted to China’s dominance of the supply chain for critical and near-critical minerals, defined in the Energy Act of 2020 as minerals “essential to the economic or national security of the United States.”S&P Global Commodity Insights, “China’s Critical Minerals Dominance and the Implications for the Global Energy Transition,” Energy Evolution (podcast, October 23, 2024), S&P Global, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/podcasts/energy-evolution/102324-chinas-critical-minerals-dominance-and-the-implications-for-the-global-energy-transition[4] U.S. Geological Survey. “What Is a Critical Mineral?” Accessed 14 Sept. 2025. https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-a-critical-mineral[5] China is estimated to control the global production of around 58 percent of light rare earths—rare earth elements of a lower or “lighter” atomic weight—and 90 percent of heavy rare earths.Pistilli, Melissa. “Rare Earth Metals: Heavy vs. Light (Updated 2024),” Nasdaq, May 15, 2024, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/rare-earth-metals%3A-heavy-vs.-light-updated-2024[6] Chou, William. “China’s Bureaucratic Playbook for Critical Minerals.” Hudson Institute, 9 July 2025, https://www.hudson.org/supply-chains/chinas-bureaucratic-playbook-critical-minerals-control-technology-transfer-william-chou[7] In fact, more than half of the critical minerals the US currently imports are originally sourced from Chinese producers or refiners.“‘Rare Earths and Critical Minerals: China and the United States,’” The New York Times, April 16, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/16/climate/rare-earths-critical-minerals-china-united-states.html[8] The geopolitical ramifications of such an arrangement pose strategic risks to the US and its allies, especially if China were to restrict access to these minerals. In April 2025, China imposed export controls on seven rare earth elements in response to US tariff increases.Baskaran, Gracelin, and Meredith Schwartz. “The Consequences of China’s New Rare Earths Export Restrictions.” CSIS, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 14 Apr. 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/consequences-chinas-new-rare-earths-export-restrictions[9] And in October 2025, China expanded its export controls to deny exports of its rare earth elements for use by foreign militaries.“China, Trump, Xi, and Rare Earths: Defense, Critical Minerals, and Trade War Tariffs,” CNBC, October 14, 2025, https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/14/china-trump-xi-rare-earth-defense-critical-mineral-trade-war-tariffs.html[10] If diplomatic disputes were to intensify, the access of the US and its allies to critical and near-critical minerals would be put in jeopardy.

The past two decades have witnessed a surge in DRC-based Chinese-owned mining operations, fundamentally altering both the country’s mineral economy and its role in the global supply chain for critical minerals. Driven by soaring demand, especially for copper and cobalt, China’s expansion in the Congolese mining sector has reconfigured not only local extraction and export patterns but also international geopolitical dynamics.

The rise of these Chinese-owned mines in the DRC can be traced back to the early 2000s.Colville, Alex. “Mining the Heart of Africa: China and the Democratic Republic of Congo.” The China Project, 7 June 2023, https://thechinaproject.com/2023/06/07/mining-the-heart-of-africa-china-and-the-democratic-republic-of-congo/[11] As China’s economic ascent accelerated, its government encouraged state-owned and private firms to invest abroad in pursuit of resource security. The African Copperbelt, which passes through southern DRC and contains some of the world’s richest reserves of copper and cobalt, became a focal point of this effort.“New Initiative to Support Artisanal Cobalt Mining in the DRC.” Miningreview, 1 Apr. 2021, https://www.miningreview.com/battery-metals/new-initiative-to-support-artisanal-cobalt-mining-in-the-drc/[12] By 2007, landmark deals were struck, such as a $9 billion Sicomines agreement between the DRC and a consortium of Chinese companies, including Sinohydro and China Railway Engineering Corporation.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] These deals traded long-term mining access in exchange for investments in local infrastructure, although delivery on these promises has fallen short, according to the Council on Foreign Relations.Schoonover, Nathan. “China in Africa: March 2025.” Council on Foreign Relations, 28 May 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/china-africa-march-2025[14] An agreement announced in January 2024 commits the Chinese businesses to a $7 billion investment in the DRC’s mining infrastructure, underscoring the continuing evolution of these arrangements.Rolley, Sonia, et al. “Chinese Companies to Invest up to $7 Billion in Congo Mining Infrastructure | Reuters.” Reuters, Reuters News & Media Inc., 27 Jan. 2024, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinese-invest-up-7-bln-congo-mining-infrastructure-statement-2024-01-27/[15]

Unfortunately, the risks of human rights violations in these mines are extremely high. Much of the mining at these industrial mines is performed by “artisanal miners,” freelance workers who perform the mining using shovels or pickaxes in chemically toxic environments for the equivalent of a few US dollars per day.“Red Cobalt: Congo DRC Mining,” NPR, February 1, 2023, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/02/01/1152893248/red-cobalt-congo-drc-mining-siddharth-kara[16] Artisanal mining is prohibited by law, but is still present at most mines in the DRC.“Red Cobalt: Congo DRC Mining,” NPR, February 1, 2023, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/02/01/1152893248/red-cobalt-congo-drc-mining-siddharth-kara[16] Miners are often physically abused, sexually harassed, and discriminated against based on their race or gender.U.S. Department of Labor, Forced Labor in Cobalt Mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Final Report (Washington, DC: Bureau of International Labor Affairs, May 30, 2023), https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/DRC-FL-Cobalt-Report-508.pdf[17] Studies have revealed that many of these labor rights violations have been committed in several Chinese-owned mines, including the Kamoto Mine, the Tenke Fungurume Mine, Sicomines, Metalkol Roan Tialings Reclamation (RTR) Mine, and Dewiza Mine.U.S. Department of Labor, Forced Labor in Cobalt Mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Final Report (Washington, DC: Bureau of International Labor Affairs, May 30, 2023), https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/DRC-FL-Cobalt-Report-508.pdf[17]

The significance of the expansion of these mines is far-reaching. Chinese firms control or hold majority stakes in almost three-fourths of cobalt and copper mines in the DRC, including the Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine, the Tenke Fungurume Mine, and the Kisanfu Mine. The consolidated Chinese presence now accounts for an estimated 70% of the DRC’s cobalt exports and a substantial share of its copper production, effectively shaping global market prices and supply reliability.Gregory, Farrell, and Paul Milas. “China in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A New Dynamic in Critical Mineral Procurement.” US Army War College - Strategic Studies Institute, 17 Oct. 2024, https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/SSI-Media/Recent-Publications/Article/3938204/china-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-a-new-dynamic-in-critical-mineral/[18] The DRC itself produces more than 70% of the world’s cobalt and about 10% of its copper, making the country indispensable to the global economy.Gregory, Farrell, and Paul Milas. “China in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A New Dynamic in Critical Mineral Procurement.” US Army War College - Strategic Studies Institute, 17 Oct. 2024, https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/SSI-Media/Recent-Publications/Article/3938204/china-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-a-new-dynamic-in-critical-mineral/[18] 'DRC - African Green Minerals Observatory.” Africangreenminerals.com, 2021, www.africangreenminerals.com/countries/democratic-republic-of-congo[19]

The development and expansion of these mining projects have dramatically increased mineral output. For instance, Sicomines’ annual copper production more than doubled between 2017 and 2023, rising from 115,000 to over 206,000 metric tons, while cobalt output has also grown sharply.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] Similar trends are evident in the China Molybdenum Co. Ltd (CMOC)-owned Tenke Fungurume and Kisanfu mines, which now rank among the world’s largest producers of copper and cobalt.

US economic and national security depend on the secure supply of cobalt and copper. However, since the late 20th century, the US has been import-dependent, both on Chinese direct imports and imports from other countries originating from Chinese production or refinery sites.T. E. Graedel and Alessio Miatto, U.S. Cobalt: A Cycle of Diverse and Important Uses (U.S. Department of Energy, June 2022), https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1981742[20] The White House, “Adjusting Imports of Copper into the United States,” July 30 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/07/adjusting-imports-of-copper-into-the-united-states/[21] Cobalt is an important material in the production of lithium-ion batteries. The omnipresence of these batteries is felt in everyday life, powering phones, laptops, tablets, and electric vehicles (EVs). Lithium-ion technology is a crucial component of America’s expanding EV market and clean energy implementation more broadly. Moreover, cobalt alloys are unique in their resistance to extreme heat, which enables their use in military-grade technology, aircraft engines, and space technology.Ames Laboratory, “Researchers Discover a New Multi-Element Alloy That Could Improve Energy Use in Gas Turbines,” May 30 2025, Ames Laboratory News, U.S. Department of Energy, https://www.ameslab.gov/news/researchers-discover-a-new-multi-element-alloy-that-could-improve-energy-use-in-gas-turbines[22]

Copper is also critical for its ability to conduct electricity, a capacity that has become increasingly important with the development of energy-intensive technologies like artificial intelligence (AI). A modern electric grid, with the capacity for AI data centers, will be possible only with a secure supply of copper. Copper’s conductivity, ductility, efficiency, and recyclability position it as integral to alternative energy sources, notably solar and wind.A New Energy Transition Is Beginning And ..., Accessed 20 Sept. 2025. https://www.copper.org/resources/market_data/infographics/copper-and-the-clean-energy-transition-brochure.pdf[23] To meet rising energy demands and provide the infrastructure for their delivery, the US relies on copper.

Facility Background

Sicomines

Sicomines is a copper and cobalt mine located in the Mutshatsha Territory of the Kolwezi District, within the Lualaba Province in southeastern DRC.Livingstone, Emmet. “Uncertainties Remain With Renegotiated Chinese Mining Deal in DRC,” Voice of America, January 26, 2024, accessed August 22, 2025, https://www.voanews.com/a/uncertainties-remain-with-renegotiated-chinese-mining-deal-in-drc-/7458908.html[24] It is a joint venture between Chinese companies that retain a 68% stake, and Congo’s state mining company.Rakotoseheno, Solofo. “Sicomines: How the EITI in DRC Helped Secure 4 Billion in Additional Revenue,” EITI, March 25, 2024, https://eiti.org/blog-post/sicomines-how-eiti-drc-helped-secure-4-billion-additional-revenue[25] The mine was created in 2007 after the DRC, under President Kabila, signed an agreement valued at around $9 billion US that gave the companies exploitation licenses to extract the minerals; in return, the companies were expected to invest about $3 billion into infrastructure. Rakotoseheno, Solofo. “Sicomines: How the EITI in DRC Helped Secure 4 Billion in Additional Revenue,” EITI, March 25, 2024, https://eiti.org/blog-post/sicomines-how-eiti-drc-helped-secure-4-billion-additional-revenue[25] Landry, David. 'The Risks and Rewards of Resource-for-Infrastructure Deals: Lessons from the Congo's Sicomines Agreement' (Working Paper, 2018), https://int.nyt.com/data/documenttools/01911-sicomines-workingpaper-landry-v6/fd147a81df0bb6b9/full.pdf[26]

By 2016, however, China had only spent about $750 million on infrastructure development, significantly below its initial promise of $3 billion.Gregory, Farrell, and Paul Milas. “China in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A New Dynamic in Critical Mineral Procurement.” US Army War College - Strategic Studies Institute, 17 Oct. 2024, https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/SSI-Media/Recent-Publications/Article/3938204/china-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-a-new-dynamic-in-critical-mineral/[18] Moreover, a state auditor from the DRC claimed that the mines, now estimated to be worth at least $93 billion, had been significantly undervalued at the signing of the 2008 agreement. This was in no small part due to the initial agreement’s lack of a formal estimation of the reserves and the DRC’s limited negotiating power given their need for the funds.Baskaran, Gracelin. “A Window of Opportunity to Build Critical Mineral Security in Africa,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (commentary, October 10, 2023).[27] Jansson, Johanna. 2011. “Recipient Government Control under Pressure: The DRC, the IMF, China and the Sicomines Negotiations.” Draft paper presented at the 4th European Conference on African Studies, Uppsala, Sweden, June 15-18, 2011. Department of Society and Globalisation, Roskilde University. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.aegis-eu.org/archive/ecas4/ecas-4/panels/1-20/panel-7/Johanna-Jansson-Full-paper.pdf[28] As a result, by January 2024, DRC President Tshisekedi had secured a new agreement with several amendments, including an increased infrastructure development fund of $7 billion.Rakotoseheno, Solofo. “Sicomines: How the EITI in DRC Helped Secure 4 Billion in Additional Revenue,” EITI, March 25, 2024, https://eiti.org/blog-post/sicomines-how-eiti-drc-helped-secure-4-billion-additional-revenue[25] Though the agreement failed to increase the government’s equity stake in Sicomines, it included that China would be responsible for royalty payments to the government.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13]

Sicomines has 8.1 million metric tons of copper reserves and 0.5 million metric tons of reserves, and has consistently grown in its annual production.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] In the first half of 2016, Sicomines produced 28,000 metric tons of copper, on track to produce 82,000 metric tons by the end of the year.Landry, David. 'The Risks and Rewards of Resource-for-Infrastructure Deals: Lessons from the Congo's Sicomines Agreement' (Working Paper, 2018), https://int.nyt.com/data/documenttools/01911-sicomines-workingpaper-landry-v6/fd147a81df0bb6b9/full.pdf[26] By 2023, the mine’s annual output was 206,612 metric tons of copper and 5,951 metric tons of cobalt, contributing to the $3.83 million in direct cobalt imports from China that the US received that year, as well as the likely tens of millions in indirect imports that ultimately originated from Chinese-owned mines.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] “Cobalt in United States,” Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), accessed September 3, 2025, https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/cobalt/reporter/usa[29]

Tenke Fungurume Mine

Tenke Fungurume (TFM) is one of the world's largest copper-cobalt mines, located in the Lualaba Province of the DRC on a concession spanning 1,500 square kilometers.NS Energy, 'Tenke Fungurume Copper-Cobalt Mine - Project Profile,' accessed September 13, 2025, https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/tenke-fungurume-copper-cobalt-mine/[30] Considered the world’s fifth-largest copper mine and second-largest cobalt mine, TFM is a cornerstone of the global supply chain for critical minerals essential for clean energy technologies.The Copper Mark, 'Case study - Tenke Fungurume Mining,' accessed September 13, 2025, https://coppermark.org/case-study-tenke-fungurume-mining/[31] Its reserves are estimated at 176.8 million metric tons, with high-grade ore grading 2.1% copper and 0.30% cobalt.

The mine's ownership transitioned decisively to Chinese control between 2016 and 2019. China Molybdenum Co. Ltd (CMOC) acquired a 56% stake from US-based Freeport-McMoRan in 2016 and consolidated its control by purchasing the remaining private shares in 2019, achieving an 80% ownership stake.Reuters, 'Freeport to sell Tenke copper interest to China Molybdenum for $2.65 billion,' May 9, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-freeport-mcmoran-divestiture-china-mo-idUSKCN0Y00L5[32] The remaining 20% is held by the DRC's state-owned mining company, Gécamines. This acquisition placed a strategically vital asset under the control of a leading Chinese company, aligning with Beijing's goal of securing upstream resources for its dominant electric vehicle and battery manufacturing industries.

Under CMOC's control, TFM has undergone aggressive expansion. After an initial expansion phase from 2011-2013, CMOC launched a third expansion in 2021 with a $2.51 billion investment aimed at doubling production capacity.Reuters, 'China Moly to spend $2.5 billion to double copper, cobalt output at Congo mine,' August 6, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/china-moly-spend-251-bln-boost-congo-copper-cobalt-mine-output-2021-08-06/[33] This investment boosted output to 280,297 metric tons of copper and 21,592 metric tons of cobalt by 2023.Fatshimetrie, 'Mining performance and community impact in the DRC in 2023,' April 13, 2024, https://eng.fatshimetrie.org/2024/04/13/fatshimetrie-mining-performance-and-community-impact-in-the-drc-in-2023/[34] CMOC has set an ambitious target to raise the combined annual output from TFM and the nearby Kisanfu mine to between 800,000 and 1,000,000 metric tons of copper by 2028, which would solidify its position as a top global producer.Mining.com (Reuters), 'CMOC to double copper output at Congo mines to 1 million tonnes by 2028,' February 27, 2024, https://www.mining.com/web/cmoc-to-double-copper-output-at-congo-mines-to-1-million-tons-by-2028/[35]

However, this expansion has been accompanied by significant political and social challenges. A major dispute over royalty payments erupted in 2022, leading the DRC government to halt TFM's exports for nearly a year.Reuters, 'CMOC's Congo mine suspends copper and cobalt exports,' July 17, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/cmocs-congo-mine-suspends-copper-cobalt-exports-2022-07-17/[36] The dispute was resolved in April 2023 after CMOC agreed to pay Gécamines $800 million.Reuters, 'China's CMOC agrees to pay $800 million to end row with Congo's Gécamines,' April 19, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinas-cmoc-agrees-pay-800-mln-end-row-with-congos-gecamines-2023-04-19/[37] Additionally, TFM has faced scrutiny over environmental practices, though it became the first mine in Africa to receive "The Copper Mark" ESG certification in 2024, signaling a commitment to responsible mining practices.The Copper Mark, 'Tenke Fungurume Mining receives The Copper Mark,' July 15, 2024, https://coppermark.org/tenke-fungurume-mining-receives-the-copper-mark/[38]

Kisanfu Mine

The Kisanfu Mine (KFM) stands as one of the world’s largest and highest-producing copper and cobalt mines, playing a pivotal role in both local and global supply chains.“World’s ten largest cobalt mines,” Mining-Technology, accessed October 18, 2025, https://www.mining-technology.com/marketdata/ten-largest-cobalts-mines/[39] The mine is located in the African Copperbelt, the largest and most productive sediment-hosted copper province in the world, which contains over 5 billion metric tons of copper ore and significant cobalt concentrations, accounting for nearly half of all copper in sedimentary deposits globally.Staff @ Geology for Investors, ‘The Central African Copper Belt,’ Geology for Investors, first published June 8, 2016, last updated June 9, 2017, https://www.geologyforinvestors.com/deposits-central-african-copper-belt/[40] And as of 2024, the mine was producing 136,000 metric tons of copper.CMOC Group, “The DRC - Copper and Cobalt,” CMOC Group, accessed September 19, 2025, https://en.cmoc.com/html/Business/Congo-Cu-Co/[41]

The Kisanfu Mine is operated by China Molybdenum Co. Ltd (CMOC) Kisanfu Mining SARL, which is 95% owned by KFM Holding and 5% owned by the government of the DRC.MiningDataOnline, “KFM (Kisanfu) Mine,” Major Mines & Projects, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.miningdataonline.com/property/873/KFM-Kisanfu-Mine.aspx[42] KFM Holding itself is 75% owned by CMOC Group Ltd. and 25% by Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Ltd (CATL).MiningDataOnline, “KFM (Kisanfu) Mine,” Major Mines & Projects, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.miningdataonline.com/property/873/KFM-Kisanfu-Mine.aspx[42] In other words, CMOC Group has a 71.25% stake in the mine, Contemporary Amperex has a 23.75% stake, and the DRC maintains a 5% stake. In addition to the Kisanfu Mine, CMOC—the world’s leading producer of copper and cobalt—has an 80% stake in Tenke Fungurume Mining SA.CMOC Group, “The DRC - Copper and Cobalt,” CMOC Group, accessed September 19, 2025, https://en.cmoc.com/html/Business/Congo-Cu-Co/[41]

Methodology

This project started with a comprehensive overview of the African critical mineral supply chain, studying the role that China played in both the production and refining of critical minerals such as graphite, cobalt, and copper in ten of the top African producers by country. Based on the especially large proportion of copper and cobalt output controlled by Chinese companies in the DRC, this study was narrowed to the country and then further to the Lualaba Province, which is where the majority of the cobalt and copper production is located within the country.

This project will analyze the recent physical developments in three DRC mines: the Kisanfu Mine, the Tenke Fungurume Mine, and the Sicomines. These mines were chosen because they produce high levels of cobalt and copper in the DRC, and all had Chinese-owned companies as the majority stakeholders. This is why other large mines like the Frontier Mine—which is owned by the Luxembourg-based Eurasian Resources Group— or low-producing Chinese mines—like Minière de Kalumbwe Myunga (MKM)—were not included.The Cobalt Institute, Cobalt Market Report 2024 (London: The Cobalt Institute, May 2025), https://www.cobaltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cobalt-Market-Report-2024.pdf[43] GlobalData, “Democratic Republic of the Congo: Five Largest Surface Mines in 2021,” GlobalData Insights, accessed October 19, 2025, https://www.globaldata.com/data-insights/mining/democratic-republic-of-the-congo--five-largest-mines-in-2090645/[44] Moreover, each of the selected mines also underwent significant recent on-the-ground developments, which could potentially be indicative of current or future changes in other similar mines.

To maximize the amount of usable data, this research combines open-source Google Earth satellite imagery with commercially available Maxar Technologies imagery. The analysis gives an overview of the types of equipment, infrastructure, and activity that exist in the mine. In addition, this investigation tracks the developments over time, including physical expansions, signs of construction, and varying levels of activity to determine if the mine is expanding operations and ramping up output. This analysis also examines past indicators of expansion, such as the clearing of forestry, to predict whether an expansion is planned in the future.

The satellite data analysis is then complemented by background research. Using verified sources, this research examines the mine’s recent production outputs, any relevant political developments or legislation, the major stakeholders (including Chinese-owned companies), and any other pertinent factors. The background research helps to contextualize the satellite data analysis and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the causes for the developments within a particular mine.

DRC Mine Analysis

Description and General Trends

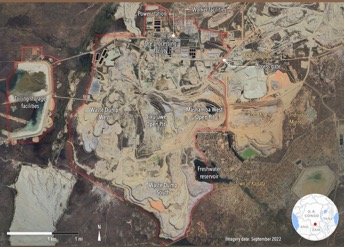

The Sicomines campus covers an area of around 11.5 square kilometers, divided into several sections (see Figure 1, Sicomines Campus).Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] The westmost section contains the tailing storage facilities (TSF), which are structures designed to contain the residue produced from the extraction and processing of the cobalt and copper minerals.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] World Bank, Tailings Storage Facilities, Good Practice Note on Dam Safety, Technical Note 7 (Washington, DC: World Bank, April 22, 2021), accessed August 9, 2025.[45] To the east and southeast of the TSF are two waste dumps where waste rock, or rock without valuable minerals, is placed.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] ACTenviro, “Mining Waste,” accessed August 9, 2025, ACTenviro, https://www.actenviro.com/mining-waste/[46]

The power station, worker facilities, and ore processing facilities are located in the northern area of the mine.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] In the central and western part of the mine, there are two mining extraction sites: the Dikuluwu Open Pit and the Mashamba West Open Pit.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] These are the primary spots for the extraction of the copper and cobalt minerals.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13] ScienceDirect, “Open-Pit Mining,” ScienceDirect Topics, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/open-pit-mining[47] Finally, in the southeastern part of the mine, there is a freshwater reservoir.Zimmerman, Jacqueline. 'Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals,' Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf[13]

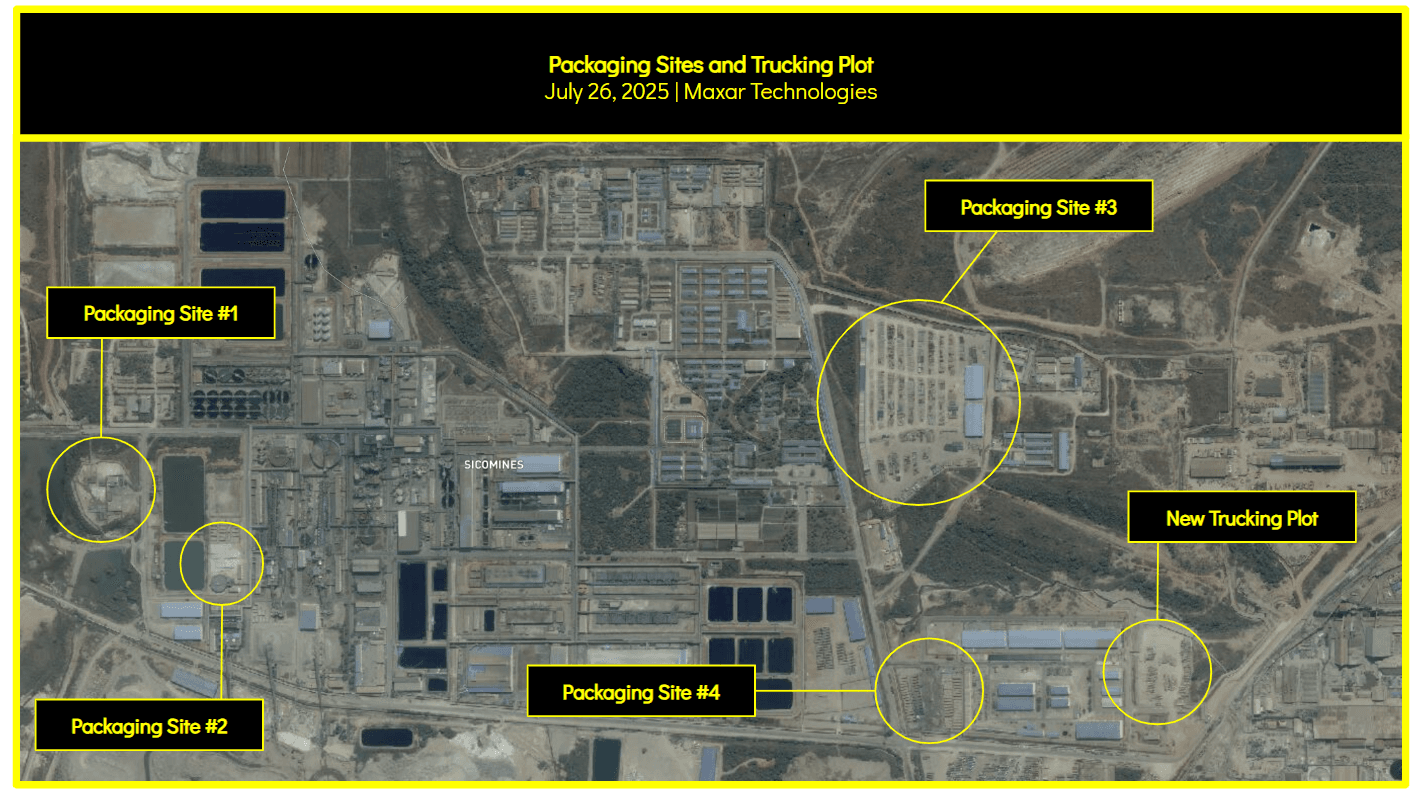

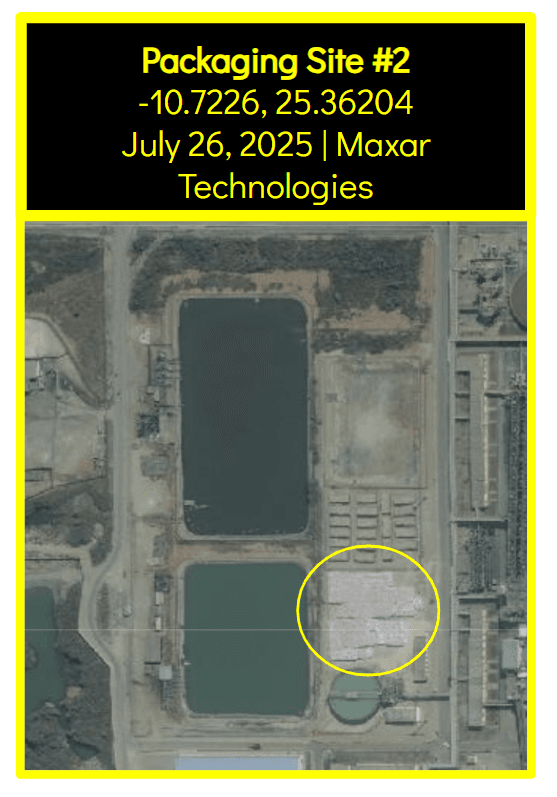

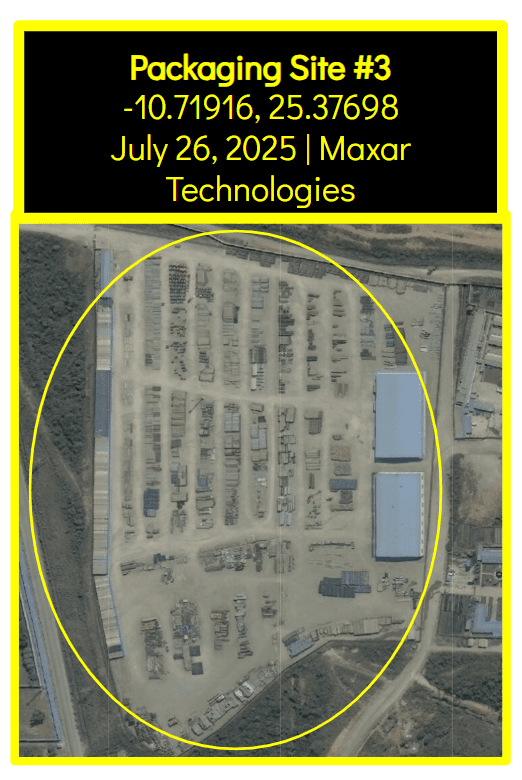

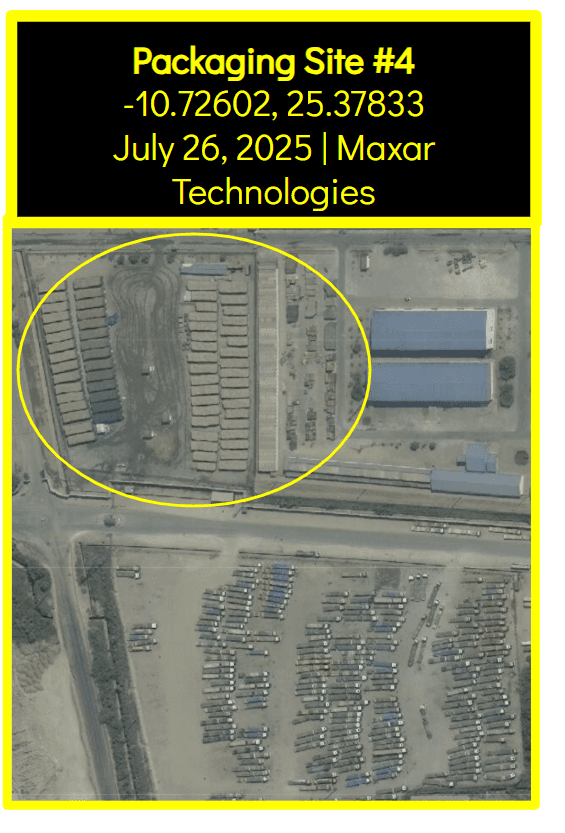

The ore processing facility has at least four sites with packaged cobalt and copper (see Figure 2, Overview of Packaging Sites and Trucking Plot). Two of the sites are located on the western sides of the ore processing facility, with Packaging Site #1 (see Figure 3) located at the westmost side and Packaging Site #2 (see Figure 4) located approximately 200 meters eastward. Packaging Site #3 (see Figure 5) is located on the northeastern side of the mine, close to the worker facilities.

Packaging Site #4 (see Figure 6) is located south of the third site, near the access gate, as shown in Figure 2. This is likely the final station before the packaged cobalt and copper are shipped, given the dozens of transport trucks, high level of car activity, and the location right next to the exit out of the mine. Moreover, between August 21, 2024, and April 30, 2025, a new trucking plot (see Figure 7) was paved, which would allow for more transport trucks to reside. It is likely this was an attempt to increase their ability to transport packaged copper and cobalt quickly.

Finally, there were several other markers of high levels of activity across the campus. The worker dormitories section consists of 100+ buildings, which, combined with additional reports, means that approximately 3,000 individuals were employed at this mine.“The Chinese Power Grab in the DRC,” GB Reports, June 28 2019, https://www.gbreports.com/article/the-chinese-power-grab-in-the-drc[48] There are multiple mining drainage pools distributed throughout the campus, which show there had to be a large level of mining production, given that these pools are formed from the interaction of mining activity with water. There are also several haul and regular roads connecting the different sections of the mine, which points to a need to accommodate a high level of intra-mine traffic.

Notable Developments

(Click through the image carousel for Figures 8-11)

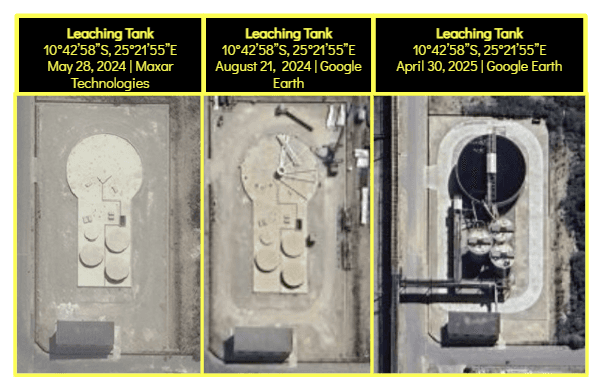

Leaching is the process of extracting minerals from ore by dissolving them to separate useful minerals from the insoluble ore. Stirred leaching is the kind of leaching that typically occurs in a leaching tank, using a stirring leaching device. Between August 21, 2024, and April 30, 2025, a probable leaching tank was added to the Sicomines campus (see Figure 8, Leaching Tank). Because stirred leaching is often used for high-grade copper ores, the addition of this structure would likely mean the mine is moving towards more strongly prioritizing high-grade copper production.

Additionally, three probable fuel tanks or liquid containers were added. A conveyor belt was also added, connecting the leaching tank and the building to the other structures in the mine, likely to move the ore and minerals to the different processing sites within the mine. Finally, there is a newly paved road that did not exist on May 28, 2024, but construction likely started by August 21, 2024, and was finalized by April 30, 2025.

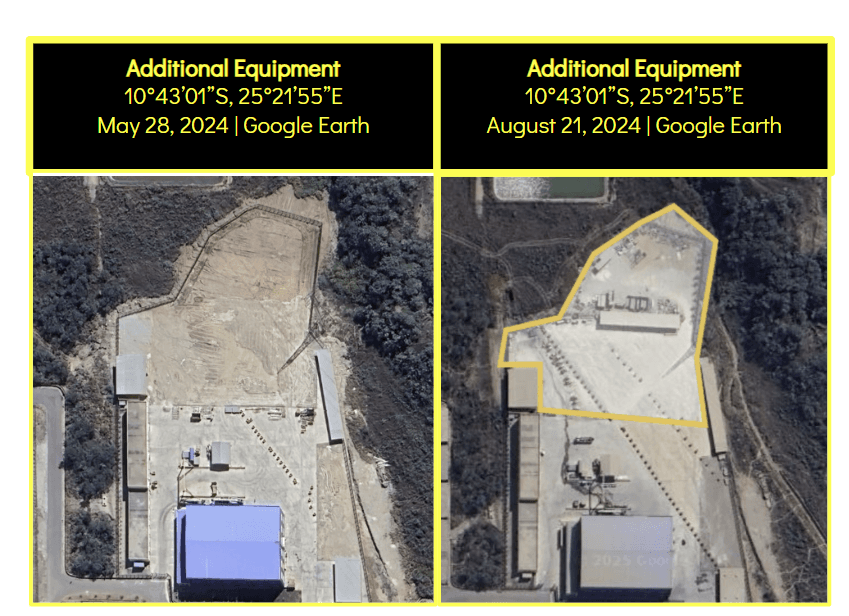

Between May 8, 2023, and August 21, 2024, several buildings, vehicles, and pieces of equipment appeared on a piece of land—approximately 7,000 square meters in size—that was previously not in use (see Figure 9, Additional Equipment). In the southwestern area of the newly used land, there was a line of thirteen probable passenger trucks and cars. Throughout this plot, there were also three buildings constructed: one small one in the southwestern area to the west of the passenger cars, one large rectangular building around the center of this plot, and one small building approximately 20 meters north of the central rectangular building. Around the center of the added plot, there are about three mining trucks and two large containers. Finally, in the northern area, there were several pieces of equipment. In short, the usage of this previously unused land demonstrates an expansion in the operations of the mine.

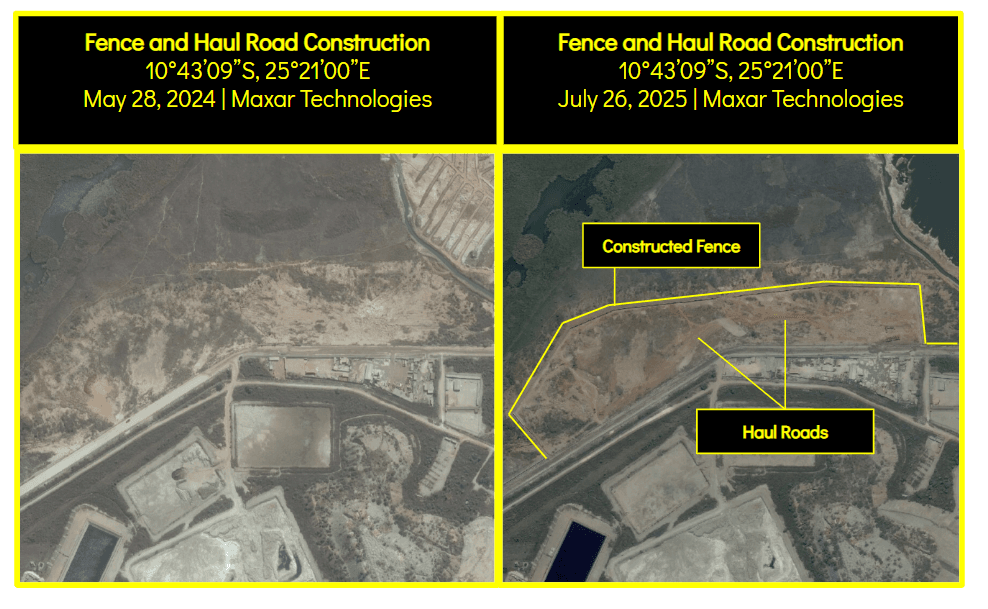

Between May 28, 2024, and July 26, 2025, a probable fence was constructed (see Figure 10, Fence and Haul Road Construction), as demonstrated by the defined line encircling this compound and the shadow that can be observed when the image is closely examined. There are also cars present on recently constructed haul roads, and approximately ten mining trucks are parked in the southeast area of this compound. The haul roads connect to the larger roads connecting the mine, but due to the lack of construction, this compound will likely be used simply as additional space to park cars and equipment for the immediate future. Ultimately, this development is another example of how this mining campus is expanding and increasing operations.

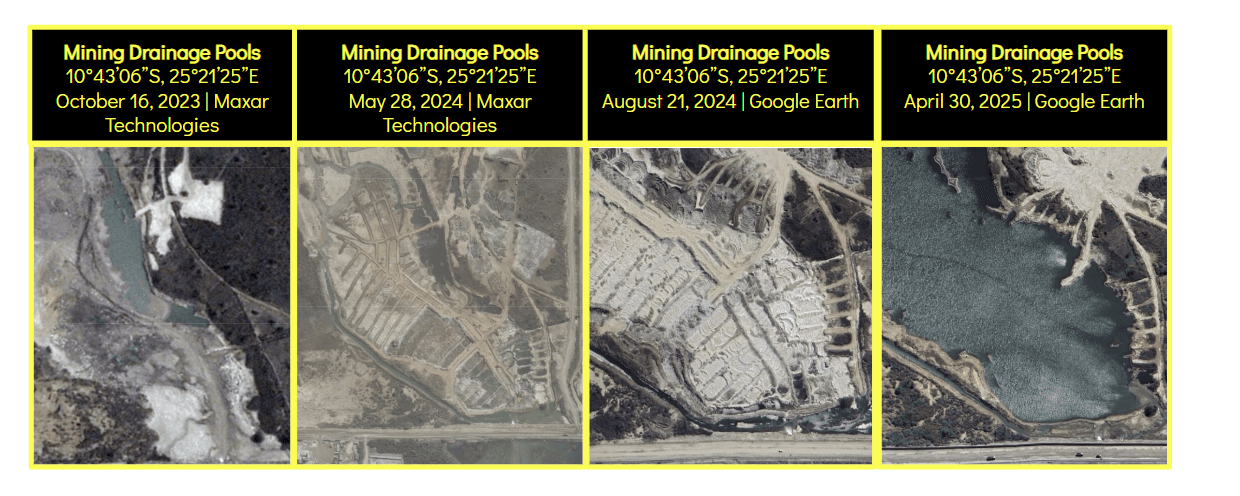

Another key development to note is the growth of the mining drainage pools, the water that comes into contact with, and drains from, active or inactive mining operations.U.S. Geological Survey, “How Does Mine Drainage Occur?,” USGS, accessed August 25, 2025, https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/how-does-mine-drainage-occur[49] For most of 2023, the mining drainage areas in this area had been relatively minimal, with the general amount of water produced remaining relatively constant up through May 28, 2024 (see Figure 11, Mining Drainage Pools). By August 21, 2024, these pools seemed to have dried up, but by April 30, 2025, not only had the pools returned, but they had expanded into a full river.

Changes in mining pool volume raise the question of whether precipitation played a role in compounding the effects of these mine pools, especially given that June to August are the dry seasons in the DRC.“Democratic Republic of Congo,” Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.comesa.int/democratic-republic-of-congo-2/[50] However, it’s important to note that the southern region of the DRC, including the Lualaba Province, experiences less precipitation than other parts of the country.“Democratic Republic of Congo,” Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.comesa.int/democratic-republic-of-congo-2/[50] Moreover, even if one assumes that the lack of mining drainage in August 2024 is the result of a lack of precipitation, there is still a massive increase in mining pool volume before April 30, 2025, in relation to previous years. As a result, our team assesses that there was likely a spike in operations in the months preceding April 30, 2025.

In total, Sicomines is showing signs of several developments. First, there has very likely been a substantial increase in operations. An increase in mining pool area, the increase in equipment on previously unused land, and the construction of intra-mine infrastructure all show that Sicomines is scaling up operations. Finally, the addition of leaching tanks means they are likely also increasing their on-site processing capacity, specifically for high-grade ores.

Tenke Fungurume Mine

Description and General Trends

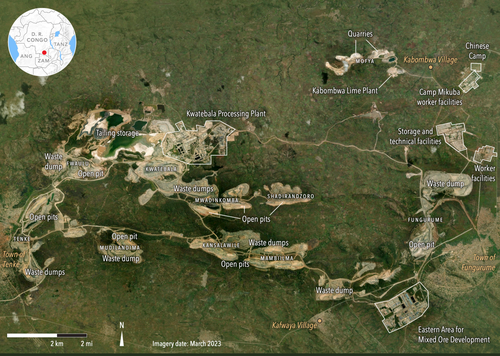

The TFM campus is a vast industrial complex comprising multiple open-pit mines, extensive processing facilities, and logistical support areas (see Figure 12, Tenke Fungurume Campus Overview). The primary extraction sites include the Kwatebala and Mwadinkomba pits, which are connected by a dense network of haul roads.

The heart of the operation is the modern Solvent Extraction-Electrowinning (SX-EW) facility, where ore is processed into 99.99% pure copper cathodes and cobalt hydroxide. Key components of this facility, visible in satellite imagery, include a grinding and milling circuit, massive circular thickeners for separating ore concentrate from waste liquid, and a long EW tankhouse for final metal plating. The site is also characterized by sprawling waste rock dumps and tailings storage facilities (TSFs) that have expanded in tandem with production increases.

Notable Developments

(Click through the image carousel for Figures 13-15)

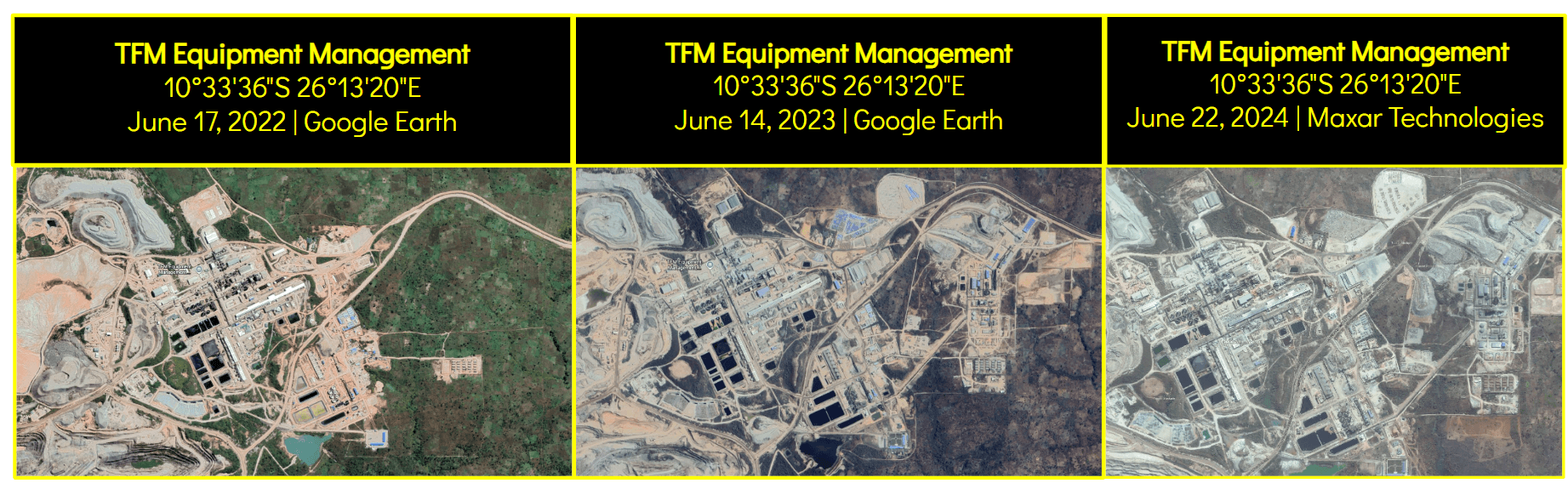

Satellite imagery confirms a period of intense and continuous expansion across the TFM site, aligning with CMOC's publicly stated investment goals. Analysis of the TFM Equipment Management Department reveals a significant increase in logistical operations. Imagery from mid-2024 shows a heightened presence of haul trucks and other vehicles compared to previous years (see Figure 13, TFM Equipment Management). This area expanded spatially by over 1.2 square kilometers between July 2022 and June 2023 alone, which signifies a major scale-up of mining and transport activity needed to feed the expanded processing plants.

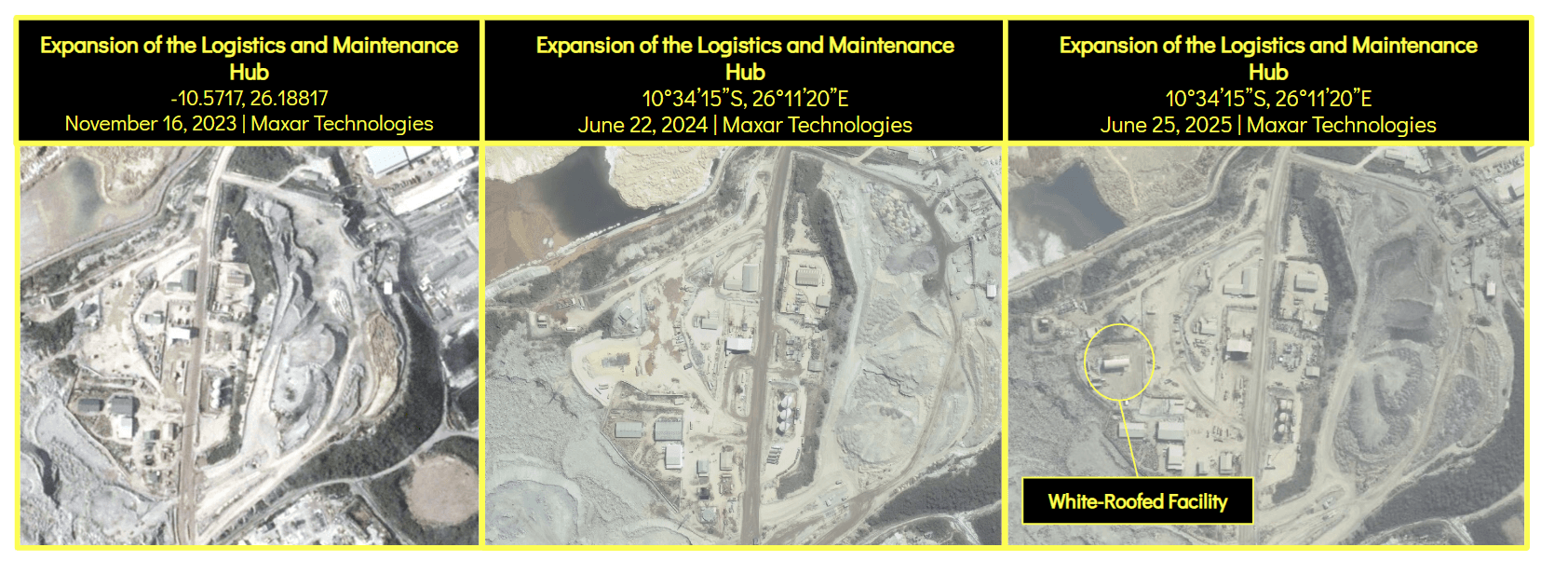

The mine's ancillary and logistics hub saw significant development between November 16, 2023, and June 25, 2025 (see Figure 14, Expansion of the Logistics and Maintenance Hub). The most prominent change is the construction of a large, white-roofed building, likely a new workshop or warehouse, which is absent in the November 2023 and June 2024 imagery. Additionally, the ground throughout the site appears more developed and graded in the June 2024 and June 2025 images, and stockpiles of materials like heavy-duty tires seem to have increased. This activity points to an investment in the mine's support infrastructure, which is essential for sustaining the higher operational tempo required by the ongoing production expansion.

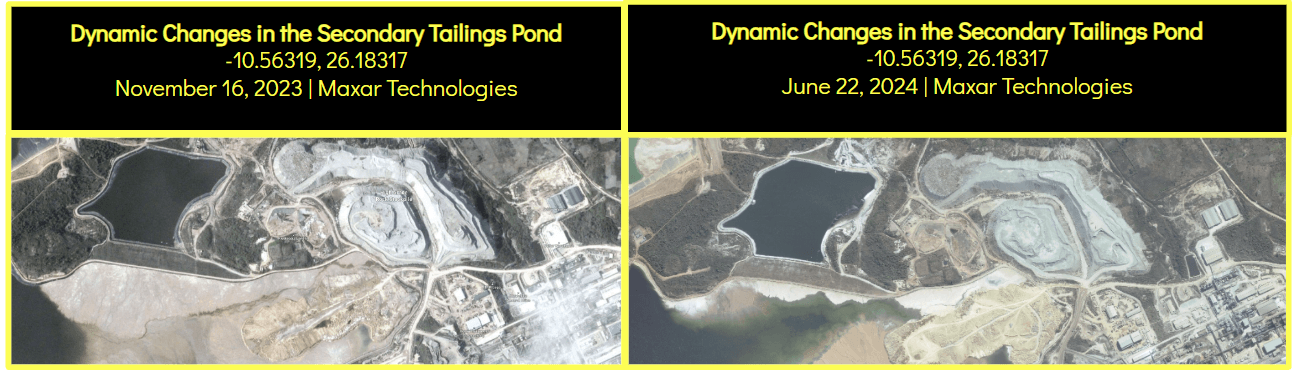

Another key detail to note is the dynamic activity within the secondary tailings and sedimentation pond (see Figure 15, Dynamic Changes in the Secondary Tailings Pond). This area is actively used to manage the site's water balance and for cyclical tailings deposition and drying. Satellite imagery clearly captures these fluctuations. In November 2023, the pond showed a large, bright, and mostly dry "beach" of deposited tailings. By June 2024, after a period where the area was largely submerged in murky brown water in late 2023, the pond had receded again. This cyclical activity reveals that the pond is a critical component of the mine's water and waste circuit, adapting to the needs of expanded processing operations.

Overall, the developments demonstrate that TFM experienced a period of significant growth between 2022 to 2025. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, there was a substantial increase in equipment, infrastructure, and facilities, showing that the mine was increasing its operations. This trend continued with the construction of at least one building and other pieces of equipment at the logistics hub of the campus between 2023 and 2024. Finally, the activity of the secondary tailings pond gave additional evidence of a considerable expansion in the past few years.

Kisanfu Mine

Description and General Trends

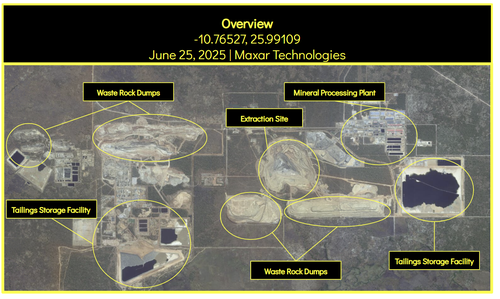

The Kisanfu mine, operated by CMOC, spans over 20 square kilometers (see Figure 16, Overview of Kisanfu Mine). The mine is divided into at least six main functional areas: an extraction site, a mineral processing plant, two sets of waste rock dumps, and two tailings storage facilities (TSF).

The extraction site is located in the middle of the mine, surrounded by haul roads to allow for the easy transportation of raw mined materials to the other stations within the mine. One of these roads goes to the mineral processing plant, which is located on the eastern side of the campus. Next to the processing plant is one of the two TSF; the other is located on the southwestern side of the mining campus. Finally, there are two sets of waste rock dumps located on the northwestern side and the south-central side of the mine.

Notable Developments

(Click through the image carousel for Figures 17-23)

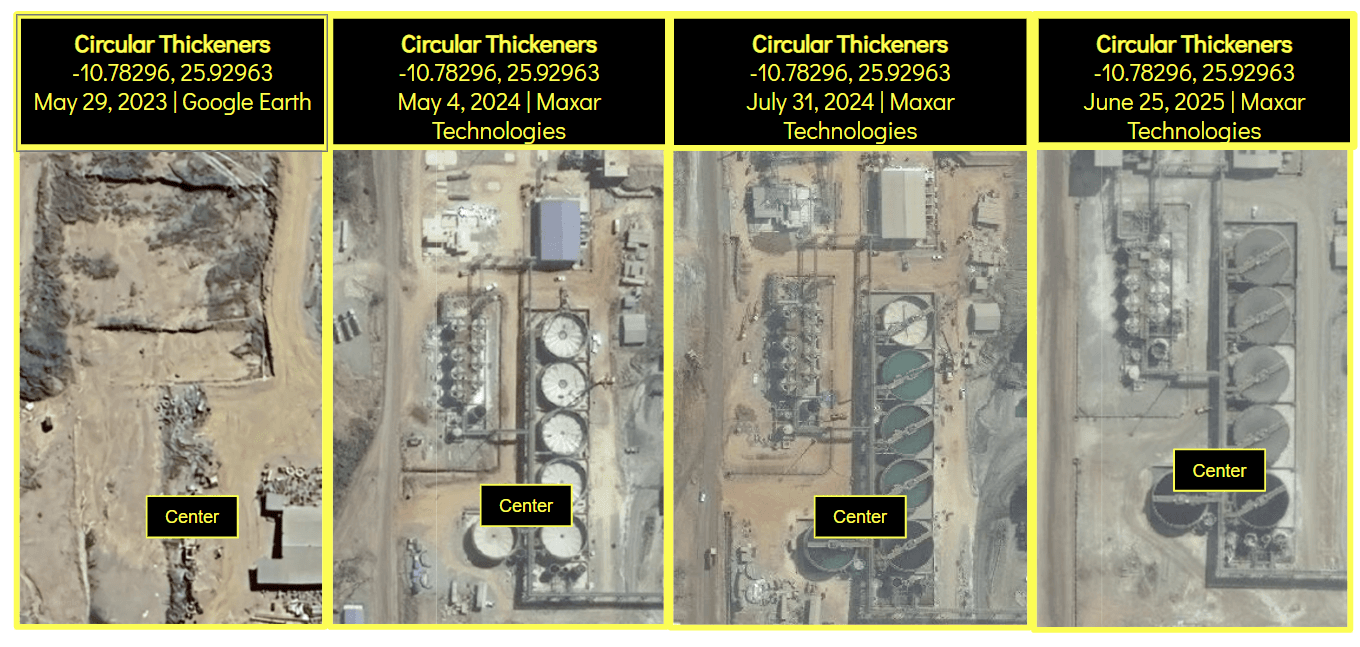

Circular thickeners play a critical role in mineral processing by separating ore concentrate from waste liquid, thereby producing a more refined material for further treatment. Between May 29, 2023, and June 25, 2025, satellite imagery reveals that six large circular thickeners were constructed (see Figure 17, Circular Thickeners). The intermediary photos showing the thickeners without lids and the surrounding construction vehicles further provide evidence of ongoing work, and the building of the thickeners demonstrates the mine’s push to scale up processing.

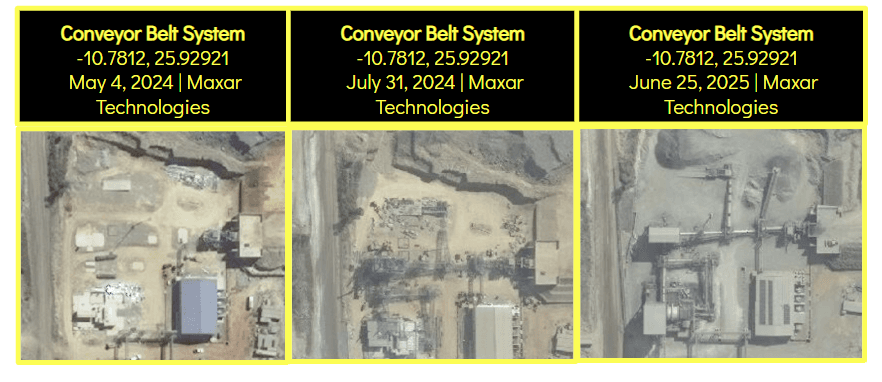

Another significant addition between May and July 2024 was a rectangular structure whose highly reflective surface, as captured in imagery, demonstrates it may have been constructed from metal (see Figure 18, Conveyor Belt System). While its exact function remains uncertain due to limited image clarity, its design and placement reveal that it is likely a conveyor belt system. Such equipment is essential for transporting raw ore from extraction zones to processing facilities, further pointing toward an effort to streamline and accelerate ore processing.

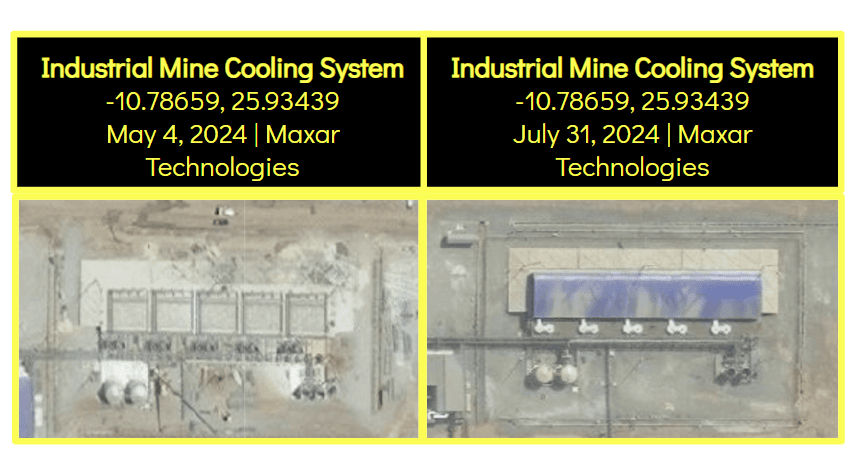

Satellite imagery from the same May–July 2024 period shows the emergence of a blue-roofed facility (see Figure 19, Industrial Mine Cooling System). This structure was not present in 2023 and appears to have been completed with the addition of a roof by mid-2024. Based on its design, particularly the white circular features resembling fans, it is likely an industrial mine cooling system, which would imply an expansion of underground mining operations, as coolers are critical to maintaining safe temperatures in subterranean shafts. The addition of such infrastructure highlights CMOC’s commitment to deeper extraction, expanding the scale and depth of Kisanfu’s mining activity.

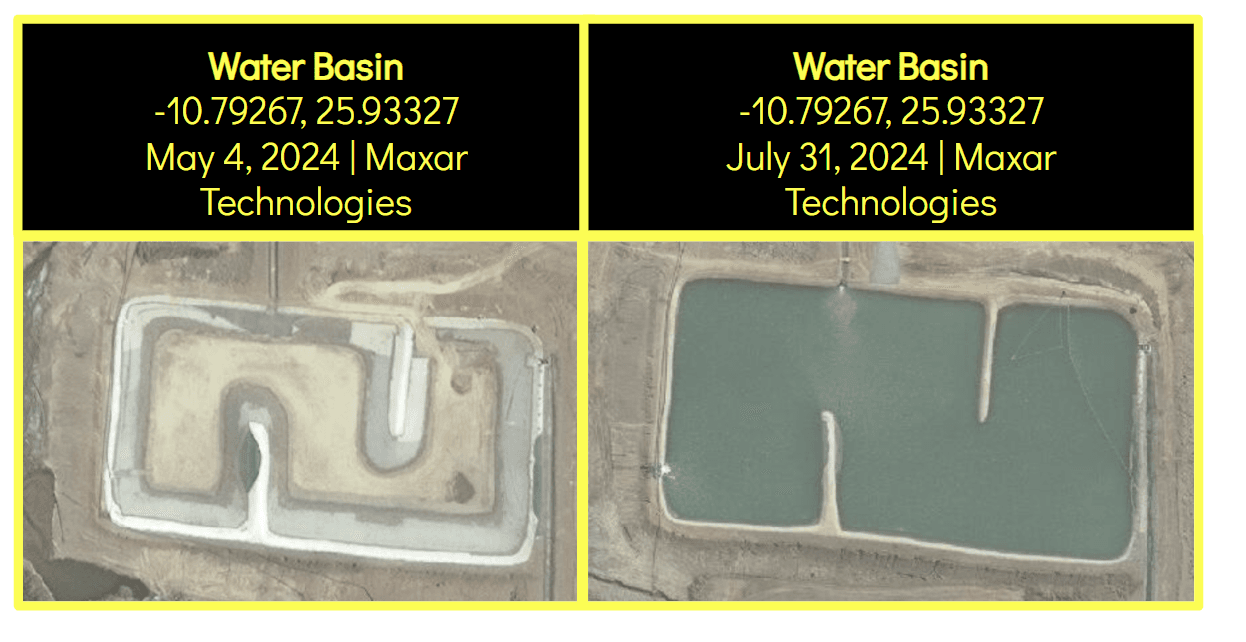

Another development occurred where satellite comparisons between May and July 2024 revealed a transition from dry land to water-filled basins (see Figure 20, Water Basin). These changes are consistent with increased mine drainage, which typically results from expanded mining activity that exposes and interacts with groundwater sources. Drainage accumulation provides indirect evidence of heightened operations, as intensified extraction often leads to elevated water management challenges. As a result, this further demonstrates a significant increase in mining operations throughout this period.

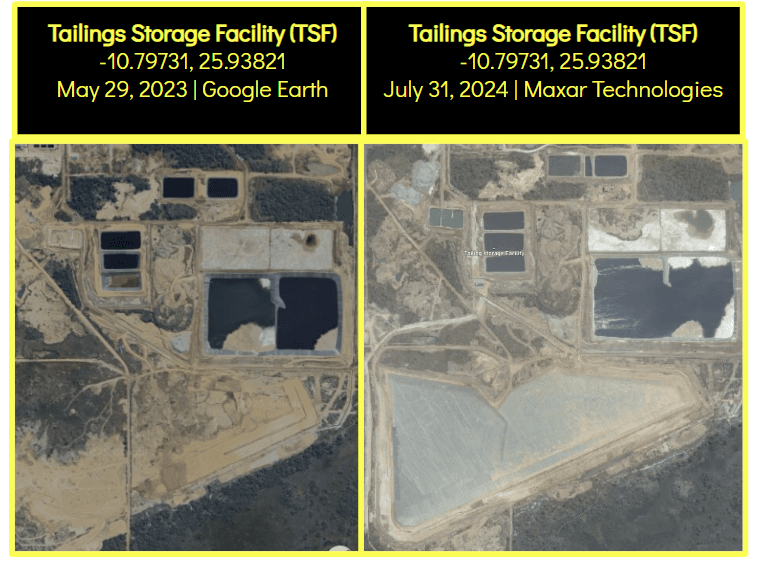

The expansion of waste storage facilities is also visible. A new TSF was established between 2023 and 2024, reflecting the mine’s rising output (see Figure 21, Tailings Storage Facility). Because tailings storage is essential for managing the residue from ore processing, the creation of another TSF underscores both the scale of recent production and the environmental demands of accommodating larger volumes of waste.“What are Tailings,” Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration (SME), accessed [your access date], https://www.smenet.org/What-We-Do/Technical-Briefings/What-are-Tailings[51]

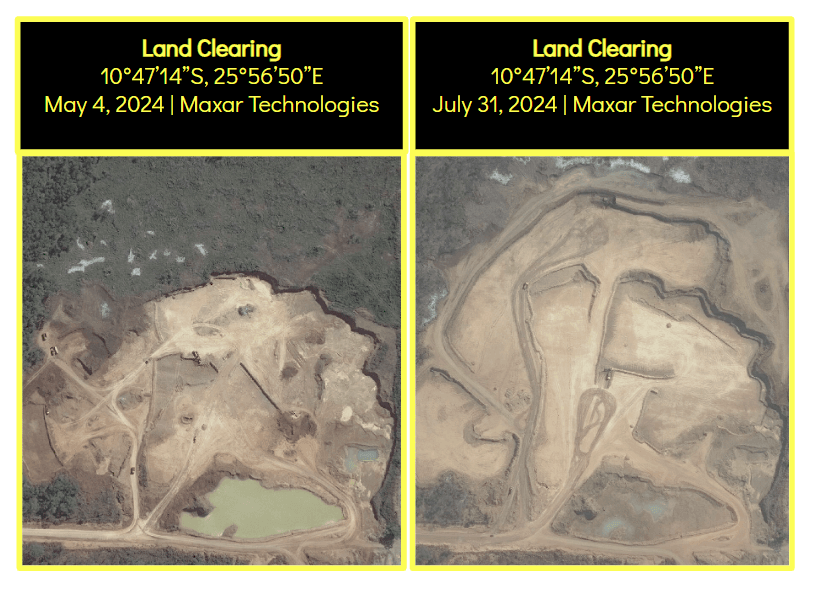

The clearing of land and vegetation was observed between May and July 2024 (see Figure 22, Land Clearing). Although uneven and somewhat irregular, this clearing may indicate preparation for future mine expansion, whether through additional infrastructure or extended extraction zones. Such preemptive land-use change is often a precursor to large-scale construction or operational shifts.

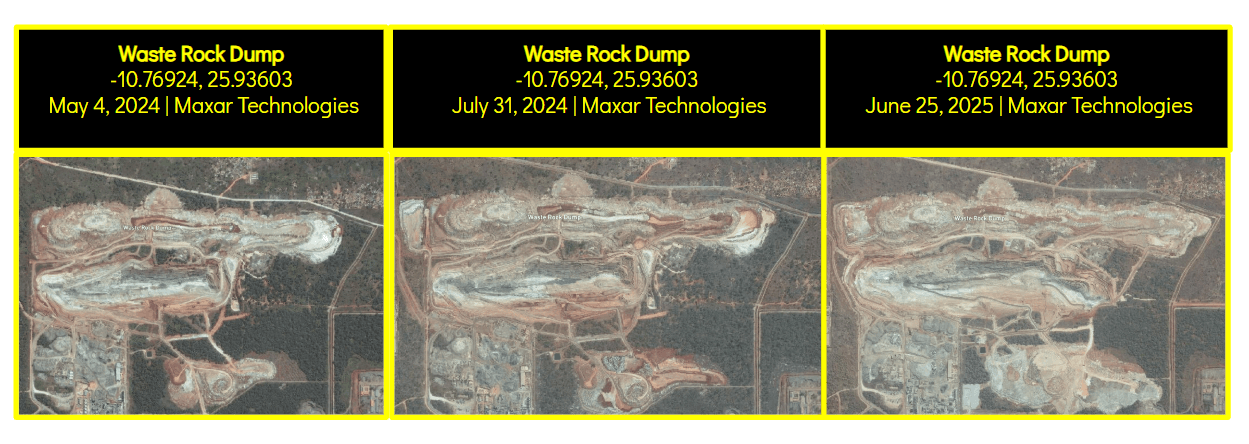

Similarly, imagery shows the waste rock dump expanding in two stages: first between May and July 2024, and again by June 25, 2025 (see Figure 23, Waste Rock Dump). Waste rock, which lacks economically valuable minerals, inevitably grows in volume alongside productive extraction. Its expansion, therefore, mirrors the overall increase in mining intensity.

Taken together, these developments illustrate a period of rapid expansion at Kisanfu between 2023 and 2025. The addition of processing capacity through new thickeners, the likely installation of a conveyor system, the possible construction of underground cooling infrastructure, the creation of new tailings storage, the accumulation of mine drainage, and the steady growth of waste rock deposits all point toward one conclusion: CMOC is not only sustaining but actively scaling up its operations at Kisanfu. These physical changes reflect both immediate increases in production and preparation for continued long-term growth, further entrenching Kisanfu’s role as one of the most important copper-cobalt mines in the world.

Conclusion

Satellite imagery of the three mines shows that Chinese companies are rapidly increasing ore production on each of their campuses. Each of the mining facilities is adding intra-mine infrastructure, equipment, and vehicles that will allow them to rapidly scale up operations in the coming years. Increase in the volume of water basins and mining drainage pools, as well as expansions of waste rock dumps, provide further evidence that the production levels of the mines are increasing at a notable rate.

In addition to increasing raw production levels, Chinese-owned mines in the DRC seem to be significantly expanding their on-site processing capacity. Imagery has tracked the construction of circular thickeners, conveyor belt systems, and other similar processing equipment. Moreover, the construction of additional tailings storage facilities and leaching tanks provides additional evidence that these mines are looking to maximize their processing power.

Finally, Chinese-owned mines in the DRC are looking to the future. Historically, the clearing of forestry has served as an accurate indicator of a future expansion of operations. There have been several instances of forestry clearance across mines, which means that mines likely have future expansion plans on the way.

It is important to note that more information is needed to determine whether these patterns of expansion are unique to Chinese-owned mines or are being witnessed at other major mines as well. Either way, based on these visual indicators for increased ore production, greater on-site processing capacity, and integration of renewable imagery, these mines could help China solidify its dominance in the cobalt and copper supply chains.

References

- Desmond Egyin, “Addressing China’s Monopoly over Africa’s Renewable Energy Minerals,” Wilson Center Africa Up Close (blog), April 1 2025, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/addressing-chinas-monopoly-over-africas-renewable-energy-minerals

- Government of Canada, “Copper Facts,” Natural Resources Canada – Minerals and Mining Data, accessed July 2025, https://natural-resources.canada.ca/minerals-mining/mining-data-statistics-analysis/minerals-metals-facts/copper-facts

- Baumann-Pauly, Dorothée. “Why Cobalt Mining in the DRC Needs Urgent Attention,” Council on Foreign Relations Blog, accessed July 2025, https://www.cfr.org/blog/why-cobalt-mining-drc-needs-urgent-attention

- S&P Global Commodity Insights, “China’s Critical Minerals Dominance and the Implications for the Global Energy Transition,” Energy Evolution (podcast, October 23, 2024), S&P Global, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/podcasts/energy-evolution/102324-chinas-critical-minerals-dominance-and-the-implications-for-the-global-energy-transition

- U.S. Geological Survey. “What Is a Critical Mineral?” Accessed 14 Sept. 2025. https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-a-critical-mineral

- Pistilli, Melissa. “Rare Earth Metals: Heavy vs. Light (Updated 2024),” Nasdaq, May 15, 2024, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/rare-earth-metals%3A-heavy-vs.-light-updated-2024

- Chou, William. “China’s Bureaucratic Playbook for Critical Minerals.” Hudson Institute, 9 July 2025, https://www.hudson.org/supply-chains/chinas-bureaucratic-playbook-critical-minerals-control-technology-transfer-william-chou

- “‘Rare Earths and Critical Minerals: China and the United States,’” The New York Times, April 16, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/16/climate/rare-earths-critical-minerals-china-united-states.html

- Baskaran, Gracelin, and Meredith Schwartz. “The Consequences of China’s New Rare Earths Export Restrictions.” CSIS, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 14 Apr. 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/consequences-chinas-new-rare-earths-export-restrictions

- “China, Trump, Xi, and Rare Earths: Defense, Critical Minerals, and Trade War Tariffs,” CNBC, October 14, 2025, https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/14/china-trump-xi-rare-earth-defense-critical-mineral-trade-war-tariffs.html

- Colville, Alex. “Mining the Heart of Africa: China and the Democratic Republic of Congo.” The China Project, 7 June 2023, https://thechinaproject.com/2023/06/07/mining-the-heart-of-africa-china-and-the-democratic-republic-of-congo/

- “New Initiative to Support Artisanal Cobalt Mining in the DRC.” Miningreview, 1 Apr. 2021, https://www.miningreview.com/battery-metals/new-initiative-to-support-artisanal-cobalt-mining-in-the-drc/

- Zimmerman, Jacqueline. "Sicomines Copper-Cobalt Mine: Chinese Financing for Transition Minerals," Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2025. https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/Sicomines_Copper_Cobalt_Mine_Chinese_Financing_for_Transition_Minerals.pdf

- Schoonover, Nathan. “China in Africa: March 2025.” Council on Foreign Relations, 28 May 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/china-africa-march-2025

- Rolley, Sonia, et al. “Chinese Companies to Invest up to $7 Billion in Congo Mining Infrastructure | Reuters.” Reuters, Reuters News & Media Inc., 27 Jan. 2024, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinese-invest-up-7-bln-congo-mining-infrastructure-statement-2024-01-27/

- “Red Cobalt: Congo DRC Mining,” NPR, February 1, 2023, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/02/01/1152893248/red-cobalt-congo-drc-mining-siddharth-kara

- U.S. Department of Labor, Forced Labor in Cobalt Mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Final Report (Washington, DC: Bureau of International Labor Affairs, May 30, 2023), https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/DRC-FL-Cobalt-Report-508.pdf

- Gregory, Farrell, and Paul Milas. “China in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A New Dynamic in Critical Mineral Procurement.” US Army War College - Strategic Studies Institute, 17 Oct. 2024, https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/SSI-Media/Recent-Publications/Article/3938204/china-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-a-new-dynamic-in-critical-mineral/

- "DRC - African Green Minerals Observatory.” Africangreenminerals.com, 2021, https://www.africangreenminerals.com/countries/democratic-republic-of-congo

- T. E. Graedel and Alessio Miatto, U.S. Cobalt: A Cycle of Diverse and Important Uses (U.S. Department of Energy, June 2022), https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1981742

- The White House, “Adjusting Imports of Copper into the United States,” July 30 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/07/adjusting-imports-of-copper-into-the-united-states/

- Ames Laboratory, “Researchers Discover a New Multi-Element Alloy That Could Improve Energy Use in Gas Turbines,” May 30 2025, Ames Laboratory News, U.S. Department of Energy, https://www.ameslab.gov/news/researchers-discover-a-new-multi-element-alloy-that-could-improve-energy-use-in-gas-turbines

- A New Energy Transition Is Beginning And ..., Accessed 20 Sept. 2025. https://www.copper.org/resources/market_data/infographics/copper-and-the-clean-energy-transition-brochure.pdf

- Livingstone, Emmet. “Uncertainties Remain With Renegotiated Chinese Mining Deal in DRC,” Voice of America, January 26, 2024, accessed August 22, 2025, https://www.voanews.com/a/uncertainties-remain-with-renegotiated-chinese-mining-deal-in-drc-/7458908.html

- Rakotoseheno, Solofo. “Sicomines: How the EITI in DRC Helped Secure 4 Billion in Additional Revenue,” EITI, March 25, 2024, https://eiti.org/blog-post/sicomines-how-eiti-drc-helped-secure-4-billion-additional-revenue

- Landry, David. "The Risks and Rewards of Resource-for-Infrastructure Deals: Lessons from the Congo's Sicomines Agreement" (Working Paper, 2018), https://int.nyt.com/data/documenttools/01911-sicomines-workingpaper-landry-v6/fd147a81df0bb6b9/full.pdf

- Baskaran, Gracelin. “A Window of Opportunity to Build Critical Mineral Security in Africa,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (commentary, October 10, 2023).

- Jansson, Johanna. 2011. “Recipient Government Control under Pressure: The DRC, the IMF, China and the Sicomines Negotiations.” Draft paper presented at the 4th European Conference on African Studies, Uppsala, Sweden, June 15-18, 2011. Department of Society and Globalisation, Roskilde University. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.aegis-eu.org/archive/ecas4/ecas-4/panels/1-20/panel-7/Johanna-Jansson-Full-paper.pdf

- “Cobalt in United States,” Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), accessed September 3, 2025, https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/cobalt/reporter/usa

- NS Energy, "Tenke Fungurume Copper-Cobalt Mine - Project Profile," accessed September 13, 2025, https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/tenke-fungurume-copper-cobalt-mine/

- The Copper Mark, "Case study - Tenke Fungurume Mining," accessed September 13, 2025, https://coppermark.org/case-study-tenke-fungurume-mining/

- Reuters, "Freeport to sell Tenke copper interest to China Molybdenum for $2.65 billion," May 9, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-freeport-mcmoran-divestiture-china-mo-idUSKCN0Y00L5

- Reuters, "China Moly to spend $2.5 billion to double copper, cobalt output at Congo mine," August 6, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/china-moly-spend-251-bln-boost-congo-copper-cobalt-mine-output-2021-08-06/

- Fatshimetrie, "Mining performance and community impact in the DRC in 2023," April 13, 2024, https://eng.fatshimetrie.org/2024/04/13/fatshimetrie-mining-performance-and-community-impact-in-the-drc-in-2023/

- Mining.com (Reuters), "CMOC to double copper output at Congo mines to 1 million tonnes by 2028," February 27, 2024, https://www.mining.com/web/cmoc-to-double-copper-output-at-congo-mines-to-1-million-tons-by-2028/

- Reuters, "CMOC's Congo mine suspends copper and cobalt exports," July 17, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/cmocs-congo-mine-suspends-copper-cobalt-exports-2022-07-17/

- Reuters, "China's CMOC agrees to pay $800 million to end row with Congo's Gécamines," April 19, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinas-cmoc-agrees-pay-800-mln-end-row-with-congos-gecamines-2023-04-19/

- The Copper Mark, "Tenke Fungurume Mining receives The Copper Mark," July 15, 2024, https://coppermark.org/tenke-fungurume-mining-receives-the-copper-mark/

- “World’s ten largest cobalt mines,” Mining-Technology, accessed October 18, 2025, https://www.mining-technology.com/marketdata/ten-largest-cobalts-mines/

- Staff @ Geology for Investors, ‘The Central African Copper Belt,’ Geology for Investors, first published June 8, 2016, last updated June 9, 2017, https://www.geologyforinvestors.com/deposits-central-african-copper-belt/

- CMOC Group, “The DRC - Copper and Cobalt,” CMOC Group, accessed September 19, 2025, https://en.cmoc.com/html/Business/Congo-Cu-Co/

- MiningDataOnline, “KFM (Kisanfu) Mine,” Major Mines & Projects, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.miningdataonline.com/property/873/KFM-Kisanfu-Mine.aspx

- The Cobalt Institute, Cobalt Market Report 2024 (London: The Cobalt Institute, May 2025), https://www.cobaltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cobalt-Market-Report-2024.pdf

- GlobalData, “Democratic Republic of the Congo: Five Largest Surface Mines in 2021,” GlobalData Insights, accessed October 19, 2025, https://www.globaldata.com/data-insights/mining/democratic-republic-of-the-congo--five-largest-mines-in-2090645/

- World Bank, Tailings Storage Facilities, Good Practice Note on Dam Safety, Technical Note 7 (Washington, DC: World Bank, April 22, 2021), accessed August 9, 2025.

- ACTenviro, “Mining Waste,” accessed August 9, 2025, ACTenviro, https://www.actenviro.com/mining-waste/

- ScienceDirect, “Open-Pit Mining,” ScienceDirect Topics, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/open-pit-mining

- “The Chinese Power Grab in the DRC,” GB Reports, June 28 2019, https://www.gbreports.com/article/the-chinese-power-grab-in-the-drc

- U.S. Geological Survey, “How Does Mine Drainage Occur?,” USGS, accessed August 25, 2025, https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/how-does-mine-drainage-occur

- “Democratic Republic of Congo,” Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.comesa.int/democratic-republic-of-congo-2/

- “What are Tailings,” Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration (SME), accessed [your access date], https://www.smenet.org/What-We-Do/Technical-Briefings/What-are-Tailings

- The White House, “Immediate Measures to Increase American Mineral Production,” March 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/immediate-measures-to-increase-american-mineral-production/

- The White House, “Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Takes Further Action to Strengthen and Secure Critical Mineral Supply Chains,” September 20, 2024, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/09/20/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-takes-further-action-to-strengthen-and-secure-critical-mineral-supply-chains/

- U.S. Department of State, “Minerals Security Partnership,” accessed October 17, 2025, https://www.state.gov/minerals-security-partnership

Look Ahead

Production of critical and near-critical minerals at Chinese-owned mines, particularly in the DRC, will likely continue to increase as they rise both in profitability and geostrategic importance. The main question is how the US will respond. In President Trump's second term, the US prioritized executive orders that encouraged domestic production of critical minerals as defined by the Chair of the National Energy Dominance Council (NEDC), including uranium, gold, and copper.[52] Under President Biden, the US supported domestic critical mineral supply chains and formed the Minerals Security Partnership, a collaboration with countries like the United Kingdom and Australia to work with the private sector to encourage investment into strategic critical mineral projects. [53, 54] Though some of these policies have had an impact, the US is not yet on track to meet the mining production or refinery capacity levels of China. Chinese mining companies will likely continue to outproduce and outrefine Western companies, particularly American ones, for the foreseeable future.

Things to Watch

- Are there similar types of developments and expansion patterns in other Chinese-owned mines producing critical minerals?

- What will be the impact of modernized Chinese infrastructure projects, such as the Tan-Zam railway or the Sakania Dry Port, which could potentially reduce the cost of extracting cobalt from the DRC?

- Will the DRC’s export quotas discourage Chinese investment in additional mines and mine expansion?

- How will the recent peace agreements and declarations between the DRC, Rwanda, and the March 23 movement impact the operations of Chinese-owned mines? Will they help deter attacks on mining sites and reduce mineral smuggling operations?

About The Authors

B.A, Political Science and History, Yale University, Project Lead

B.A., Global Affairs, Yale University, Project Member

B.A., History, Yale University, Project Member

B.S., Applied Mathematics & Computer Science, Yale University, Project Member

B.A, History, Yale University, Project Member

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.