Overview

This report evaluates the progress of five commercial projects central to Sino-Taliban economic cooperation. GDIL finds modest progress in Chinese-backed mining and oil projects and limited progress in industrial and road projects.

The industrial and road projects have been accompanied by significant disconnects between publicized claims and on-the-ground progress.

Activity

The Global Disinformation Lab (GDIL) at the University of Texas at Austin analyzed commercial imagery, volunteer mapping services, ground photography, open press reports, and business literature to assess the progress or lack of progress of Chinese-backed projects in Afghanistan with an emphasis on the Taliban administration time period since 2021.

“Friendshoring” and securing access to critical minerals and industries are a defining point in U.S.-China competition. With the arrival of the Taliban in Kabul, there is much media speculation on the potential for the Taliban to go all-in on Chinese-funded extraction and connectivity projects that can provide a semblance of economic stability. Foreign Policy reported that, on paper, Afghanistan is one of the most mineral-rich countries in the world but historically has struggled to build its mining sector. China has funded at least 112 Belt and Road projects throughout Central Asian neighbors, underscoring the region’s significance to China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

It is important to note that lithium was a major focus of early research on this topic. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) published a research report in 2011 that stated Afghanistan is “the world’s recognized future principal source of lithium.” However, GDIL has found no substantial leads on Chinese lithium projects. As of February 2024, Afghan media reported no contracts have been signed for lithium extraction. We assess with high confidence that the Chinese government is not currently developing large-scale lithium extraction industries in Afghanistan. To do so would likely require over 10 years of lead time and billions of dollars in hard commitment before any possible output. Afghanistan’s poor connectivity, difficulty with existing Chinese projects, unstable governance, and security challenges will continue to dampen any such expectations for the foreseeable future. China has more promising ongoing projects for lithium mining in other countries such as Argentina and Namibia.

Key Findings

This report first provides background on key diplomatic developments and media reports relating to Sino-Taliban economic relations. This report then examines progress on five commercial projects designed to further Sino-Taliban economic cooperation. The main findings for each project are discussed in detail below.

Mineral and Oil Extraction Projects

Imagery analysis conducted by GDIL showed modest progress on China’s two extraction projects, the Mes Aynak Copper Mine and the Amu Darya Oil Project in Afghanistan. Based on imagery analysis and open reporting, Chinese enterprises began development on oil and copper projects in the early 2010s but achieved only limited progress before Afghan officials halted these efforts. After the Taliban takeover in August 2021, activity resumed. GDIL did not identify any other pre-existing or newly announced extraction efforts. Moreover, Taliban officials generally only refer to these two sites when discussing Chinese natural resource interests in Afghanistan.

- Mes Aynak Copper Mine – A mining campus south of Kabul designed to extract copper. According to open-reporting, a Chinese SOE has reacquired the project. Imagery analysis indicates mining preparations are taking place, but copper ore has not yet been extracted.

- Amu Darya Oil Project – Three crude oil extraction blocks in northern Afghanistan where a Chinese SOE recently restarted extraction. Imagery analysis of two facilities associated with the project noted new infrastructure additions post-Taliban takeover. Open-reporting and financial documents confirm renewed activity.

Chinese Industrial and Business Initiatives in Afghanistan

- Chinatown Kabul – GDIL assess that Chinatown Kabul, though claiming affiliation with BRI, operates as an independent venture not officially recognized by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce within the BRI framework. This complex of ten-story buildings in Kabul’s Taimani district hosts a variety of small Chinese businesses, including factories and vendors selling shoes, clothing, and textiles. Constructed in 2019, Chinatown Kabul serves as a critical entry point for Chinese investors and facilitates Sino-Afghan cooperation at the small-to-medium enterprise level.

- Chinatown Industrial Park and Kabul New City – Imagery analysis and open-source reporting indicate that the Chinatown Industrial Park, announced in April 2022, has shown limited construction progress. Despite being positioned in an area marked for upscale development and reported enthusiasm in Chinese and local media, the project does not appear to be connected to China’s official BRI overseas industrial parks. The limited development observed suggests a disconnect between stated ambitions and actual on-ground activity. After six months of construction work, only one unfinished building is evident on imagery. The Chinatown Industrial Park is Phase One of a broader development initiative, Kabul New City, which itself has seen limited progress. Despite plans to rejuvenate the effort under Taliban rule, imagery and open-source reporting indicate limited advancements on-site, with no new infrastructure observed on imagery.

Transportation Infrastructure

- Claimed Road Connecting China and Afghanistan through the Wakhan Corridor: Despite Taliban assertions that road construction began in November 2023 and involved rapid development of 50 km of dirt grading and partial asphalt, GDIL finds these claims likely exaggerated. The review, using OpenStreetMap (OSM), Google Earth, and Maxar imagery, reveals primarily dirt roads and footpaths that abruptly end before reaching the border, with inconsistent patches of well-graded dirt roads but no asphalted sections. Historical data, including tourist reports from 2019, indicate that road construction activities predated Taliban involvement, further questioning the accuracy of their statements.

Background

Beijing’s involvement in Afghanistan is driven primarily by security concerns, with a focus on stabilizing the region to prevent spillover effects into its territories. Voice of America counts more than 20 violent, non-state actors, such as Islamic State in the Khorasan (IS-K) and the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), in Afghanistan. These groups pose direct threats to regional stability and Chinese interests, evidenced by incidents like IS-K's December 2022 attack on a Kabul hotel hosting Chinese businessmen.

Despite these security challenges, there is a significant push from the Chinese and Taliban to bolster economic collaboration, as seen in the potential expansion of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) into Afghanistan and high-level diplomatic exchanges, such as the appointment of a new Chinese Ambassador to Afghanistan in September 2023. These moves are likely part of a broader strategy to enhance bilateral economic cooperation, including through potential inclusion in China’s BRI. In October 2023, the Taliban’s commitment to join BRI was marked by their participation in the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, signaling an intent to deepen economic integration.

Media and diplomatic reporting also underscore China’s interest in Afghanistan’s untapped mineral resources, which are key for its industrial needs, especially for technologies like electric vehicles. This interest is complicated by the reality of Afghanistan’s mining sector, which has been hobbled by violence and governance issues. Nevertheless, the narrative of a burgeoning Sino-Afghan economic cooperation continues to grow, shaping perceptions of a potential economic revival under the Taliban.

However, as this report will demonstrate, a significant disconnect exists between the publicized claims of Chinese progress and the reality on the ground, raising questions about the tangible outcomes of these high-profile, Beijing-backed initiatives.

Mes Aynak Copper Mine

Findings

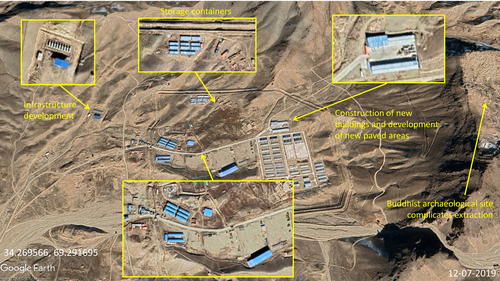

Imagery and open-source analysis by GDIL find that infrastructure development and preliminary excavation are underway at the Chinese-owned Mes Aynak Copper Mine, though copper ore extraction has not yet begun. GDIL identified new infrastructure additions on the main campus and evidence of preliminary excavation on a nearby hillside. However, as reported by Afghan media in February 2024, the extraction of copper ore remains delayed, impeded by the presence of 2,000-year-old Buddhist ruins overlaying the deposit.

Background

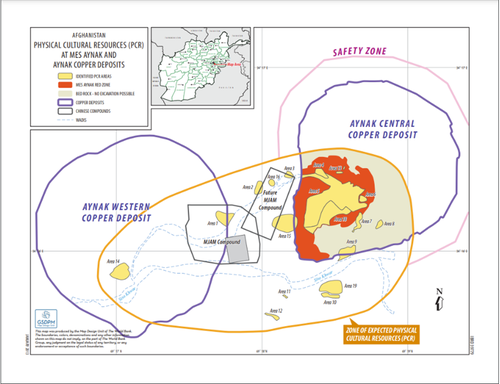

In 2008, a consortium of two Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), China Metallurgical Group Corporation (MCC) and Jiangxi Copper Company Limited (JCL), signed a $3 billion agreement with the U.S.-backed government of Afghanistan for a 30-year lease at the Mes Aynak site. This deal represents the largest foreign direct investment in Afghanistan’s history. Global Times, a China-influenced publication, reported that the site contains the world’s second-largest copper deposit. The extraction of copper from this site could generate revenues of $250-300 million per year for the Taliban. Figure 2 is a 2013 World Bank map showing the mining sites and the main campus location.

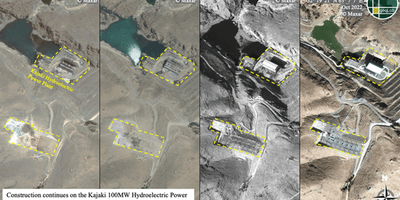

Figure 3 shows active construction on the site in 2009. Several of the buildings at the center of the facility were intended to house laborers. Dirt roads run along the property stretching into the surrounding hills where extraction was expected to take place.

Over the next ten years, the site expanded with new facilities added as shown in Figure 4. However, throughout the time of the U.S.-backed government, Mes Aynak reportedly did not produce copper, according to both MCC and Afghan officials. Preservation of the Buddhist ruins complicated extraction efforts. Moreover, attacks from the Taliban prevented the site from becoming fully operational. Issues in resettling nearby villages further delayed extraction.

Taliban Interest

Following the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban expressed interest in MCC resuming operations at the site. In April 2022, Mes Aynak was reportedly ready to resume operations after meetings between Taliban and MCC executives. Yet, the Taliban reported as recently as February 2024 that copper extraction remained delayed due to ongoing negotiations regarding the preservation of the Buddhist ruins. Figure 5 shows the site in September 2022, with few changes in activity since 2019.

Despite the declared pause from cultural heritage, imagery analysis showed a revival in general activity on site starting in August 2023. Figure 6 is a timelapse showing the excavation of the hillside west of the main campus from August to October 2023. Figure 7 from February 2024 shows snaking dirt trails were dug out of the hill face, leading to open areas with parked cars and small sheds.

Figure 8 depicts the entire Mes Aynak site as of February 2024, showing both preliminary excavations and a new structure, likely a storage shed, constructed on the main campus. Given repeated Taliban claims that copper extraction has yet to commence due to the need to preserve the Buddhist ruins, GDIL assesses with high confidence that these activities represent preliminary excavation rather than actual extraction. Moreover, no evidence of substantial water tailings or waste rock deposits was observed at the site.

Looking Ahead

After ten years of delays, new developments in Figure 8 suggest renewed momentum at the Mes Aynak copper mine. Optimistic Afghan media reporting about ongoing cultural preservation negotiations between the Taliban and MCC officials indicate that this project is set to continue. By comparison, a copper mining project in Zambia, funded and developed by Chinese companies, includes features such as tailings, dams, transport links, and on-site smelters. For Mes Aynak, analysts should wait for the appearance of tailings and waste rock deposits before confirming the commencement of copper extraction. Additionally, Zabihullah Mujahid, the spokesman for the Islamic Emirate, has announced plans to construct an airport, road, and electricity plant near the site. The appearance of these facilities in future imagery will validate the optimistic reports from the Taliban and suggest good economic health for the project.

Amu Darya Oil Project

Findings

The Amu Darya Oil project is the second confirmed and active Chinese extraction effort in Afghanistan analyzed by GDIL. Since January 2023, a Chinese company, Xinjiang Central Asia Petroleum and Gas Co. Ltd. (CAPEIC), has leased three oil blocks in northern Afghanistan. Subsequent imagery analysis of two oil field facilities showed new infrastructure developments post-transition. Open-source photos and financial documents obtained by GDIL confirm that at least one of these oil blocks is run through a Sino-Afghan joint company and is currently producing oil.

Background

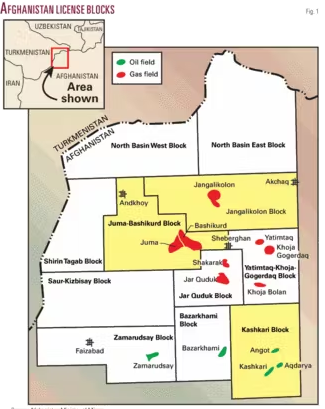

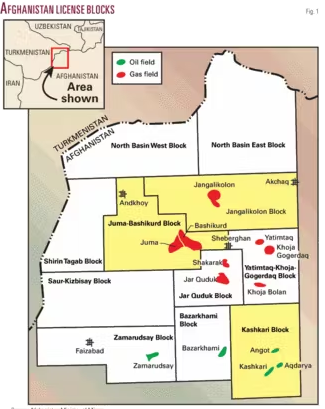

In December 2011, China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) secured a 25-year deal with the U.S.-backed Afghan Government to develop and operate oil extraction infrastructure in the Amu Darya Basin. The three oil blocks, Kashkari, Bazarkhami, Zamarudsay, are estimated to hold 87 million barrels of oil. Crude oil extraction infrastructure was constructed from 2012-2013. The project was halted in 2013 due to delays in a transport agreement with Uzbekistan. The contract with CNPC was eventually terminated due to “lack of work”. In January 2023, CAPEIC signed a $540 million deal with the Taliban to take over the project. The deal stipulated that the company would invest $140 million in the first year, and $540 million by 2026. However, Voice of America reported that, according to Taliban officials, only $49 million had been invested as of February 2024.

Note on terminology: In this section, the term “oil block” refers to the polygonal areas marked in Figure 9. The term “oil field” refers to the green-marked areas marked in Figure 9. For example, the terms “Kashkari Block” and “Kashkari Oil Field” refer to the lower-right polygonal area highlighted in yellow and the smaller oil extraction site marked in green respectively.

Figure 9 is a 2009 map of the oil and gas fields in the Amu Darya Basin, provided by Oil and Gas Journal. CAPEIC is licensed to develop the green-marked oil fields in the Kashkari, Zamarudsay, and Bazarkhami blocks. Kashkari Oil Block contains the Kashkari, Angot, and Aqdarya oil fields. Zamarudsay and Bazarkhami Oil Blocks each contain one oil field of the same name. GDIL analyzed imagery of all three oil blocks, but only identified infrastructure at the Kashkari and Angot oil fields within the Kashkari block.

Kashkari Block – Kashkari Oil Field

GDIL analysis on the Kashkari Oil Field yielded two main findings. First, following the construction of oil infrastructure in 2012, there was minimal observable activity until 2023, when CAPEIC took over the project. Figure 10 depicts the newly built Kashkari oil field in 2013. Engineers developed three main areas: four oil vats on the left, a tower and container offices in the middle, and a storage area at the bottom of the image. This general layout remained the same for the next 10 years.

In 2013, the U.S.-backed Afghan government halted the CNPC project due to delays in a transportation arrangement with Uzbekistan. According to the Diplomat, the Afghan government subsequently "threw out" CNPC. The Afghan Government did not reach out to any other company to continue work on the site between 2013-2021. GDIL analyzed nine available images on Maxar and Google Earth covering the years 2013 through 2023, noting limited activity. An Afghan caretaker force operated the wells during this time.

In 2019,the Sar-e-Pul provincial government claimed that eight wells in the Kashkari Block were active and generating revenue for the Afghan government, but Taliban fighting in the region threatened the wells' operation. Figures 11-13 represent this trend of minimal change or caretaker activity even into the Taliban era where the storage areas showed little to no movement of shipping containers until July 2023.

The second main finding regarding the Kashkari oil field is that activity increased following the Taliban's deal with CAPEIC in January 2023. This renewed activity came in two forms: an inauguration ceremony between Taliban officials and Chinese petroleum engineers and new infrastructure development on the site. The inauguration ceremony took place at the oil field in July 2023. The Taliban’s deputy prime minister for economic affairs, Abdul Ghani Baradar, attended the event. Open-source photos and financial documents obtained by GDIL indicate that the Kashkari oil field is operated by the "Afg-Chin Oil & Gas Company" (AfgChin). Ariana News, an Afghan news agency, reported that AfgChin conducted a test extraction during this ceremony. Baradar is seen in Figure 14 next to a Chinese engineer, both wearing AfgChin-marked hardhats.

GDIL geolocated photos provided by Ariana News, confirming the inauguration took place at Kashkari oil field’s facilities. Figure 15 depicts where each photo was taken. Figure 15.1 was taken facing west from the central oil derrick, showing four oil vats and a fifth, smaller vat, matching the arrangement of the oil vats on imagery. Figure 15.2 was taken from the central oil derrick (tower) facing north and overlooking the center area's entrance, container offices, and the white road. Figure 15 also shows new infrastructure developments: a flat clearing northeast of the center site and a dirt road leading to the area. Dozens of containers in the bottom storage area were also removed.

GDIL identified additional infrastructure development through broad imagery search of the surrounding area. Approximately four kilometers north of Kashkari oil field, new storage areas were built between April and September 2023. Figure 16 shows two cleared areas along the main road leading to Kashkari oil field from a nearby town. Parked trucks were observed in the top dirt area. The bottom dirt area faintly showed tire tracks. Figure 17 shows significant development five months later. The top area was paved over with concrete, blue sheds were constructed, and more trucks and shipping containers lined the area. The bottom area showed slight concrete paving near the bottom, a high presence of shipping containers, and heavy tire tracks.

Imagery analysis from April to September 2023 showed a significant resurgence in activity, coinciding with the inauguration in July 2023. Ariana News further reported that Afgchin commenced drilling 12 new wells in the Kashkari oil field. However, kmlSino-Afghan InitiativesGDIL’s detailed analysis of a five km2 around the site, using the latest available Maxar images up to September 2023, did not show new well construction.

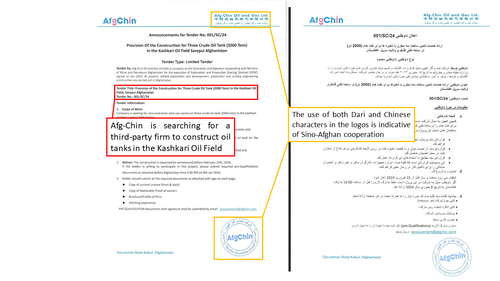

Supporting this observed increase in activity, AfgChin’s financial documents provide further evidence of ongoing oil extraction efforts. One particular document details AfgChin's progress in expanding oil infrastructure in the Kashkari oil field. Figure 18 is a financial tender document detailing AfgChin’s search for third-party construction firms to build crude oil tanks in the area. This development underscores AfgChin's expectations of continued oil extraction. The use of both Dari and Chinese in the document signals joint Chinese-Afghan cooperation.

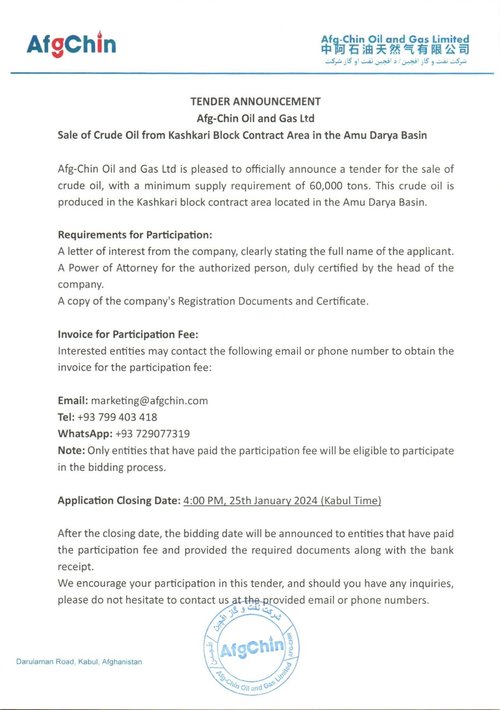

Figure 19 is an AfgChin public announcement looking for customers to buy at least 60,000 tons of crude oil, suggesting that the oil field is actively producing oil.

Kashkari Block - Angot Oil Field

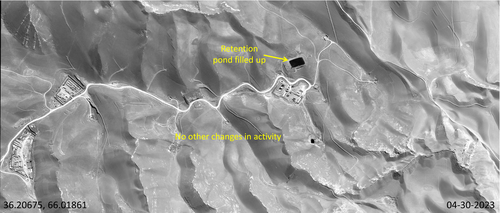

Although open-source photos of the July inauguration were geolocated to Kashkari oil field, GDIL successfully located similar facilities in the Angot oil field (~10km northeast of Kashkari oil field). Angot’s pattern of activity largely matched Kashkari’s, save for a retention pond added between 2016 and 2019 and filled in 2023. Between April and September 2023, several new facilities appeared on imagery.

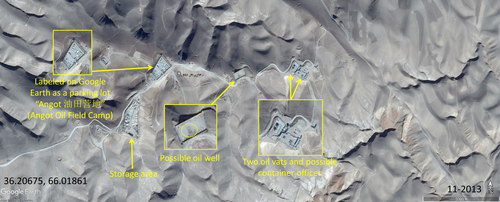

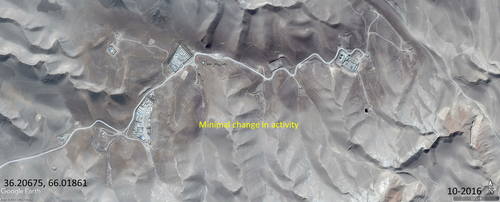

Figure 20 analysis shows Angot oil field in 2013. On the top left, a parking lot was observed with Chinese labels on Google Maps, translating to “Angot Oil Field Camp”. Other distinguishing features included a storage area, an empty space in the center with a possible oil well, and two oil vats and container offices off to the right. GDIL analysis of 13 images up to 2023 as exemplified by Figures 20-22 continued to show minimal change in activity.

After CAPEIC signed its lease in January 2023, Angot oil field underwent significant development. Figure 23 is a Sentinel timelapse capturing a fire protection pond filling to the brim over three months. Figure 24, a Maxar image from April 2023, clearly shows the pond fully filled. Fire protection ponds are used for sudden fire emergencies during oil extraction. CAPEIC likely constructed this pond as it began operating Angot Oil Field.

More significant than the fire protection pond, new facilities were added between April and September 2023, mirroring the timeline of AfgChin taking over Kashkari oil field. Figure 25 shows a possible oil derrick in the center, with new construction and oil puddles in its immediate vicinity. Below the derrick is another cleared area with new infrastructure on top of the clearing. New roads lead to both areas. Finally, several shipping containers from the storage area appear to have been removed.

Kashkari Block - Aqdarya Oil Field

Referencing the initial map of Amu Darya’s oil fields (Figure 9), kmlSino-Afghan InitiativesGDIL surveyed a five km2 area (centered at coordinates 36.11503, 66.01766 in the flyover file) east of Kashkari to assess the Aqdarya oil field.GDIL chose a five square kilometer area because the area's size overlapped with the relative depiction of Aqdarya oil field (marked in green) on Figure 9.[1] Analysis of 12 images from Google Earth and Maxar, spanning 2013 to 2023, revealed no active oil wells or facilities comparable to those in the Kashkari and Angot oil fields. The surveyed area predominantly features small residential structures and roads, with no significant industrial activity detected.

Zamarudsay and Bazarkhami Blocks

GDIL’s review of available imagery did not identify similar facilities in the Bazarkhami or Zamarudsay oil blocks. We identified the village of Bazarkhami (36.16951, 65.74647) in the approximate area that Bazarkhami oil field was marked in green on Figure 9. GDIL analysis of 10 images from Maxar and Google Earth, covering the period from 2019 to 2024, showed no active oil wells or storage facilities in thekmlSino-Afghan Initiatives surrounding 10 km2 area.GDIL chose a ten square kilometer area because the area's size overlapped with the relative depiction of Bazarkhami and Zamarudsay oil fields (marked in green) on Figure 9.[2]

We did not find village or placenames for the Zamarudsay block, so we instead approximated the oil field’s location (centered on 36.19275, 65.29552) using the Figure 9 oil field map. Once again, analysis of nine images from 2018 to 2024 failed to show active oil infrastructure.

Taliban reporting corroborated our lack of findings in these two oil blocks. In February 2024, the Taliban Ministry of Mines and Petroleum claimed that 15 wells were built in Kashkari oil field, six in Angot, and three in Aqdarya, amounting to a total of 24 active wells in the entire Afghan-controlled Amu Darya basin. There was no mention of oil wells operating in Bazarkhami or Zamarudsay blocks. However, the Ministry planned to build 12 more in Kashkari, eight in Zamarudsay, one in Bazarkhami, and two in Aqdarya by the end of 2024, raising the total to 47 wells and 3,000 tons of daily extraction.

Recent photographic evidence shows Chinese geologists actively working in the Kashkari, Zamarudsay, and Bazarkhami oil blocks, demonstrating China’s commitment to developing new oil wells in Afghanistan. On January 4, 2024, the Shanxi Institute of Geological Survey announced the completion of a four-month survey covering the three active oil blocks. While no detailed findings were disclosed, the published article about the survey highlights the team’s dedication to ”finding new strategic resources for the country”. Photos accompanying the article (Figure 26) depict Afghan and Chinese geologists conducting fieldwork on hilly terrain, likely scouting locations for new oil wells.

Looking Ahead

Overall, renewed activity under CAPEIC’s management indicates that the Amu Darya Oil Project is steadily progressing. Given the Taliban’s plans to construct 23 new wells by the end of 2024 and the activity shown in imagery analysis, GDIL expects this project to increase in output and generate a stable revenue stream for the Taliban. However, CAPEIC has only committed $49 million out of an initial $140 million commitment, with $540 million expected to be invested by 2026. Whether or not CAPEIC fulfills its funding commitment may signal the future health of the Amu Darya oil project.

Chinese Business Initiatives in Afghanistan

Findings

This section evaluates Sino-Afghan business initiatives in Kabul: Chinatown Kabul, Chinatown Industrial Park, and Kabul New City (KNC). GDIL concludes that while Chinatown Kabul will continue to host small-to-medium enterprises with backing from the Taliban, the development of Chinatown Industrial Park and KNC appears stagnant. Despite six months of reported construction, only one unfinished brick building has emerged, indicating that neither the industrial park nor KNC is likely to meet local expectations. Overall, Chinese entrepreneurship in Kabul appears to be individually driven and opportunistic, lacking a cohesive strategy from Beijing. None of the three projects are listed within official Chinese BRI documents.

Chinatown Kabul

Chinatown Kabul consists of a complex of ten-story buildings located in the western Taimani district of Kabul. Constructed in 2019, as reported by the Global Times, these buildings accommodate dozens of small Chinese enterprises that sell shoes, clothing, textiles, and various other goods. The Taliban have shown interest in the success of Chinatown Kabul, which serves as a hub for Chinese investors to build networks and explore business opportunities upon their arrival in Afghanistan. The property’s founder, Yu Minghui, has described on his company website how Chinatown Kabul “has gained a systematic understanding” of Afghanistan’s lithium, antimony, beryllium, copper, tantalum, and niobium reserves. Acting as a key middleman, Yu Minghui has reportedly been central in facilitating Sino-Afghan commercial relations for over two decades.

Figure 27 shows a recent photo of Chinatown Kabul. The red lettering on the building façade reads “The Belt and Road... China Town”, referring to the BRI. Clotheslines on several balconies indicate that the property also acts as living quarters for Chinese vendors. The sign on the right side details a variety of manufacturing industries such as energy systems, urban planning, industrial machinery, and agricultural, scientific, and technological materials. The sign suggests the property’s role as a wholesale marketplace for Chinese products related to manufacturing industries.

Open reporting indicates Chinatown Kabul continues to foster Sino-Afghan economic cooperation at the small-to-medium enterprise level. Vendors operating from the property primarily import Chinese-made consumer and capital goods, selling them to local buyers. Additionally, the property draws Chinese entrepreneurs new to Afghanistan who make use of the local business networks established by the property residents.

GDIL assesses that Chinatown Kabul is not an official BRI project with support from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, despite “The Belt and Road” signage in Figure 28. Rather, it is an independent venture supported by private individuals and enterprises. It is not listed as a project in the Chinese Ministry of Commerce’s search results regarding Afghanistan. On Belt and Road business sites, such as yidaiyilu.gov.cn, investgo.cn and beltandroad.hktdc.com, Chinatown Kabul does not appear in search results, even with Chinese language search queries. Moreover, the last official document between Afghanistan and China regarding potential BRI cooperation was a Joint Statement in 2017. No BRI-related memorandums of understanding (MoU’s) or joint statements between China and Afghanistan have been released since then, particularly since the Taliban takeover.

Chinatown Industrial Park and Kabul New City

The "Afghanistan Chinatown International Industrial Park Project," which this report refers to simply as the “Chinatown Industrial Park”, is an ambitious development planned for an area northeast of Kabul (search term: 阿富汗中国城国际产业园). The project’s manager intends for this park to evolve into a special economic zone. Additionally, Chinatown Industrial Park is meant to be the first phase of the "Kabul New City" (KNC) master plan, an Afghan project that began before the Taliban's return to power in August 2021. However, current imagery and reports indicate that development under Taliban governance has been minimal, highlighted by just one brick structure related to Chinatown Industrial Park.

In April 2022, China’s Global Times reported on a land transfer ceremony between Yu Minghui and Taliban officials for the Chinatown Industrial Park, including statements from Chinatown Kabul property managers about constructing a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) for Afghanistan. The ceremony took place at Chinatown Kabul, underscoring the connection between the two projects. While the Global Times article did not disclose construction details, it elaborated on potential business cooperation at the industrial park related to copper and lithium mining. In addition to copper and lithium mining, the park would support other sectors too, including urban construction, building material manufacturing, and consumer goods. GDIL found no mention of this industrial park on BRI websites and documents.

Figure 28 is an open-source graphic posted on Yu Minghui’s business website, showing the land transfer ceremony. When translated, the Chinese text reads, “After twenty years of investment in Afghanistan, ‘Kabul Chinatown’, a pioneer of Chinese private enterprises, has overcome many difficulties and completed all legal documents in the past three years. On April 28, 2022, Chinatown International Industrial Park obtained a transfer contract from the government of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.” Yu Minghui is seen in Figure 28 signing the transfer contract next to Taliban Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Ghani Baradar, who would go on to inaugurate the AfgChin Amu Darya project in July 2023.

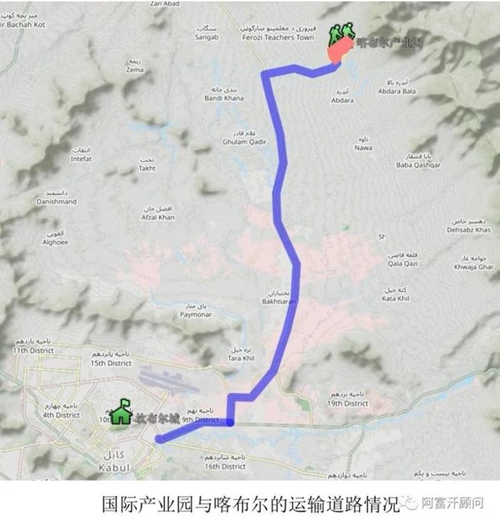

Open-source analysis of Yu Minghui’s business website yielded a location for the Chinatown Industrial Park 20 kilometers northeast of Kabul. Figure 29 depicts the route between Chinatown Industrial Park and Kabul. The home icon near the bottom is Kabul and the backpacking icon near the top is the industrial park.

Open-source analysis also found that the Chinatown Industrial Park is Phase One of a broader project, Kabul New City (KNC), an old urban development initiative commissioned by the U.S.-backed Afghan government. The Taliban expressed interest in resuming this project following their return to power in August 2021. Figure 30 is a concept map for KNC that the Taliban use to explain the vision for the project.

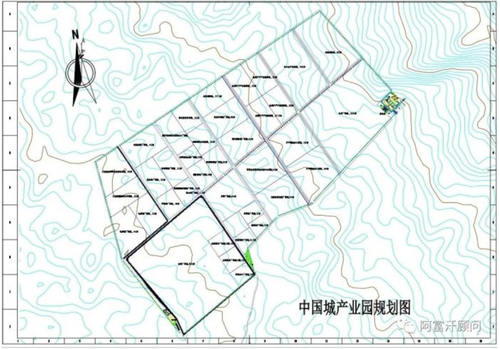

Open-reporting surrounding the Chinatown Industrial Park suggests a high number of financial backers. In November 2022, Yu Minghui claimed to the Los Angeles Times that more than 100 deals with Chinese entrepreneurs had been signed for them to move into the park when finished, with more applications being rejected. He also presented a planned map of the industrial park, as depicted in Figure 31.

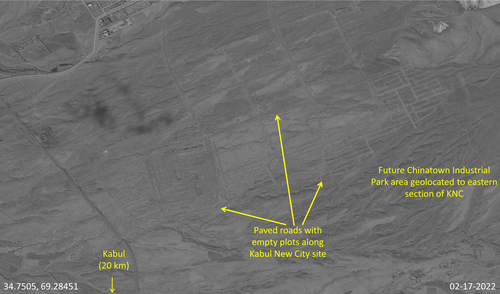

Figure 32 shows imagery in February 2022 of the remnants of Kabul New City, before the Taliban announced their intention to restart the project. The empty roads and undeveloped plots are holdovers from pre-Taliban efforts to build Kabul New City. Chinatown Industrial Park will eventually occupy the eastern section of this area, according to Yu Minghui’s business website.

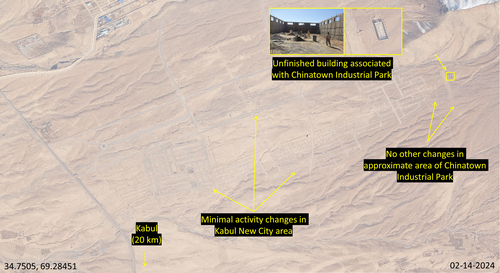

Yu Minghui began releasing photos and videos showing that Chinatown Industrial Park began construction in August 2023, suggesting that Yu Minghui’s backers have already been waiting since November 2022 to move into the park. Figure 33 is a compilation of photos taken from a Chinese business website, showing construction of only one building on the 350-acre park. The website released additional photos over the subsequent months, detailing progress on this single building. Construction of other buildings or additional infrastructure was not noted in these photo releases.

In Figure 34, GDIL geolocated these construction photos to where Chinatown Industrial Park is planned, noting the appearance of an unfinished building in February 2024. More recent imagery from April 2024 shows a roof was added. No other construction stalls or utility infrastructure, such as new electricity lines and roads leading to the building, were observed in the area associated with Chinatown Industrial Park. If over 100 Chinese entrepreneurs were already waiting to move into the park, as Yu Minghui suggested in November 2022, more construction stalls would likely appear beyond a single building. Regarding the Taliban and Kabul New City, no new activity or infrastructure was observed around the main, asphalted area noted in the center of Figure 34.

Imagery analysis suggests that open-reporting and business enthusiasm for Chinatown Industrial Park has been accompanied by insufficient construction progress. Moreover, GDIL assesses the Chinatown Industrial Park is not a BRI project. Western, Afghan, and Chinese reporting surrounding the Taliban’s interest in joining the BRI in October 2023 did not mention Chinatown Industrial Park, even though construction was ongoing during this time. Instead, reports about the industrial park appeared only on social media, in Global Times reporting, and in Chinatown Kabul’s business websites.

Little Pamir Road in the Wakhan Corridor

Findings

Despite Taliban assertions that road construction began in November 2023 and involved rapid development of 50 km of dirt grading and partial asphalt, GDIL finds these claims likely exaggerated. The review, using OSM, Google Earth, and Maxar imagery, reveals primarily dirt roads and footpaths that abruptly end before reaching the border, with inconsistent patches of well-graded dirt roads but no asphalted sections. Historical data, including tourist reports from 2019, indicate that road construction activities predated Taliban involvement, further questioning the accuracy of their statements.

Claimed Road Connecting China and Afghanistan through the Wakhan Corridor

On January 15, 2024, the Taliban announced the completion of a road through the Wakhan corridor up to the Chinese border, meant to facilitate a modern Silk Road link between the two countries. The Wakhan Corridor is a narrow strip of Afghan land that borders Tajikistan and Pakistan to the north and south, and China at its easternmost point, with a border of only 80 km.

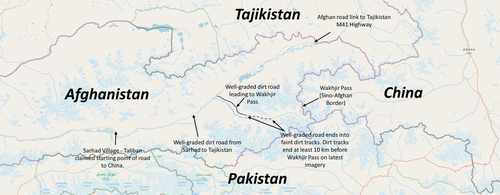

Taliban claims that the “Little Pamir Road” is completed is likely over-stated considering the Taliban’s history of exaggerated or false press statements. This includes implying the project started on their watch – a falsehood – coupled with a lack of corroborating evidence from OSM and minimal signs of paved or well-graded dirt roads in imagery analysis of likely border connections.

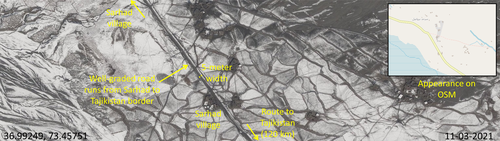

Following OSM and commercial imagery from Sarhad, the claimed point of construction origin starting in November 2022 or 2023 (murky Taliban claim of start date based on the phrase "in November of last year" in mid-January 2024 reporting), through the Wakhan corridor shows mostly dirt roads and footpaths that stop well short of the border. We cannot confirm substantial asphalt construction to major portions of the claimed road or even well-graded dirt portions, which would be required to make this claimed road a valuable economic artery.

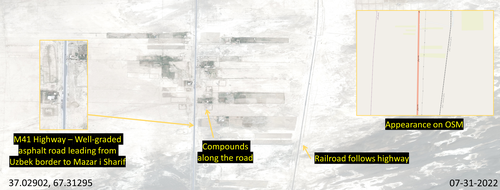

Credible tourist reporting notes survey and construction crews doing work on a road out of Sarhad before Taliban rule in 2019. This road was also planned to connect with China in the Wakhjir Pass. Taliban declarations suggest "their" construction started in November 2023 and took 90 days to complete 50 kilometers of dirt grading and partial asphalt construction. Well-graded dirt roads and asphalt are discernable on high-resolution commercial imagery. Our trace of the potential path with OSM, Google Earth, and Maxar imagery did not show major road characteristics when compared to the Big Pamir Road in Western Afghanistan, for example. See overhead imagery and OSM depiction of Big Pamir Road in Afghanistan (Figure 35), often referred to as Highway M41, especially in the context of connections with Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

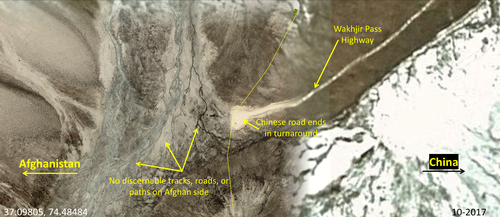

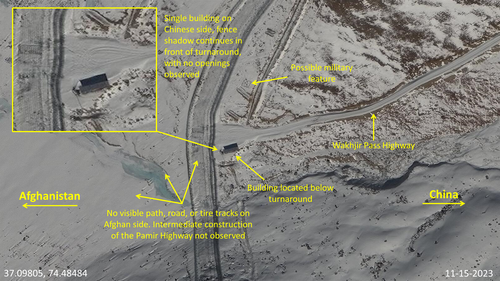

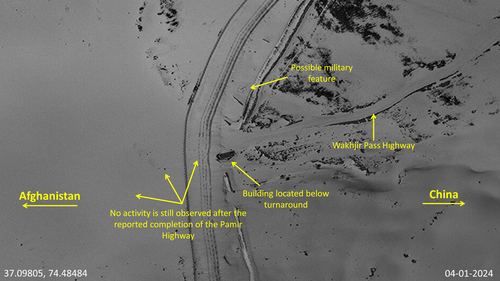

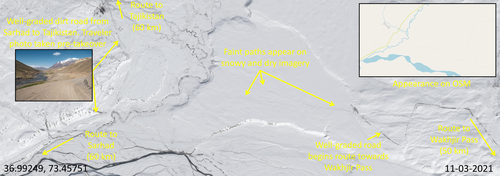

Well-graded roads are crucial for consistent movement and commerce. A well-graded road with vehicle traffic observed over time on imagery from 2017 to 2024 on China’s side of Wakhjir Pass is a likely place for a connection. We observed no well-paved signatures on Afghanistan’s side. Figures 36-39 show the Wakhjir Pass. A road on the Chinese side is clearly observed on imagery and labeled on OSM. In Google Earth and Maxar imagery ranging from 2017 to 2024, no development was observed on the Afghan side, where the claimed road link was supposed to connect with the Chinese “Wakhjir Pass Highway”.

Partial Data Explainer

Figure 37 imagery from 2017 predates Taliban road claims but was used for context as the imagery is free of snow on the Afghan side of the border. The Wakhan Corridor, in general, is only operational five months a year due to weather. The majority of available imagery is often covered in snow but we must make a call with partial data the best we can. We assume well-maintained roads would be slightly visible even in snow as they are on China's side but not Afghanistan's side.

kmlSino-Afghan InitiativesA point-of-origin trace from Sarhad initially showed fairly well-maintained and discernable dirt roads heading east toward the Wakhan Corridor. Sufficient navigable roads stretched into Tajikistan, but the roads started to become fainter as we analyzed deeper into the Wakhan Corridor. Figure 40 is a map summarizing GDIL’s analysis of dirt roads and paths leading to Tajikistan as well as to the Wakhjir Pass. The road claimed by the Taliban to connect to the Wakhjir Pass starts in Sarhad and appears well-graded (Figure 41). When the claimed road splits off from the route to Tajikistan towards the Wakhjir Pass, well-graded roads appear inconsistently alongside faint dirt trails (Figure 42). These faint dirt trails soon disappear at least 10 kilometers before the Wakhjir Pass on recent imagery (Figure 43). The route is not developed to the same extent as the Big Pamir Road.

Chinese and Western observers have expressed skepticism in the long-term viability of this claimed road based on alternative routes and construction costs in rugged terrain. There are other options in the region for commerce transport, such as routes in Pakistan where Afghanistan has even been considered to become a more official BRI partner in Pakistan-based projects. Moreover, construction costs are estimated in the tens of millions to create a well-graded and paved artery through extremely rugged terrain. At this time, China seems reluctant to support a more joint effort.

Analyzing Other Passes on the Sino-Afghan Border

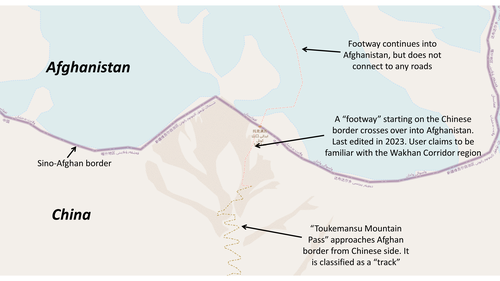

In addition to tracing the claimed road to the Wakhjir Pass in the Wakhan Corridor, GDIL analyzed three more passes on the Sino-Afghan border: Koktorok Pass, Teger-Mensudovan Pass, and Toukemansu Pass. This review did not identify additional road development on the Afghan side of the border.

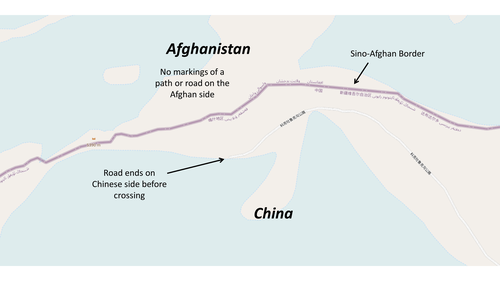

OpenStreetMap identifies four points on the Sino-Afghan border with existing Chinese roads leading into them. However, imagery analysis of these four points shows that none of them connect with any kind of road or footpath on the Afghan side. Figure 44 is a map showing the location of the four border points, along with their coordinates and elevations.

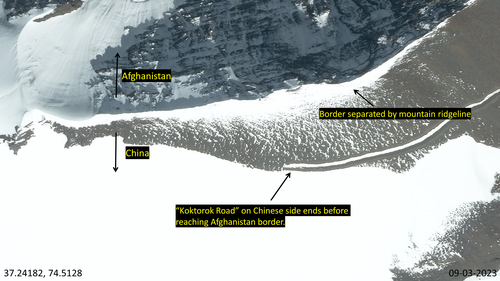

Koktorok Pass

Koktorok Road (5,334 meters) approaches the Afghanistan border from the Chinese side but terminates before reaching it, as depicted in Figures 45 and 46. The border at this location is marked by a continuous mountain ridgeline without any discernable gaps, making it an unlikely site for a road connection.

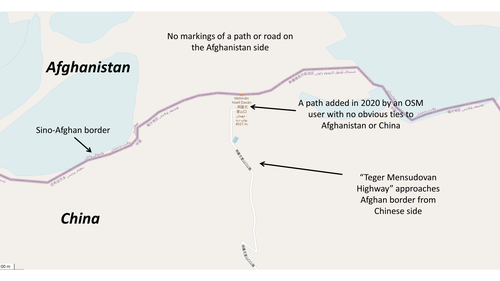

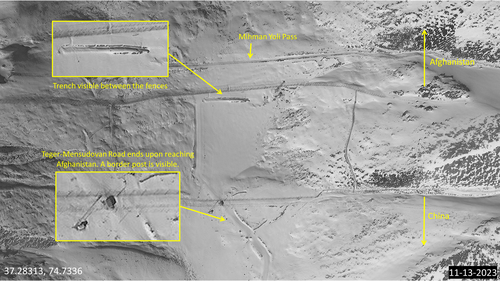

Teger-Mensudovan (Mihman Yoli) Pass

Teger-Mensudovan Road (4,926 meters) in Figure 47 shows infrastructure comparable to that at Wakhjir Pass, including a border post and fences, which are also visible in Figure 48. Despite its relatively low elevation for the region, this road experiences significant snowfall. Approaching Afghanistan from the Chinese side, the road does not appear to extend beyond the "Mihman Yoli" Pass, marked by the northernmost fence in Figure 48.

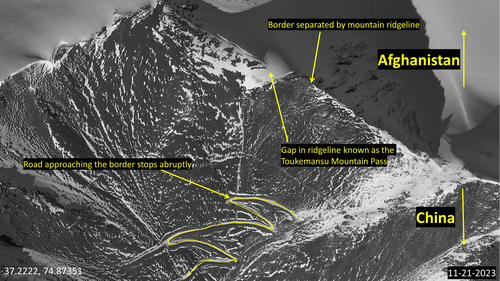

Toukemansu Mountain Pass

Toukemansu Mountain Pass (5,035 meters) in Figures 49 and 50 show another high-elevation road approaching a border defined by a mountain ridgeline. In this case, however, there is a gap in the ridgeline labeled the Toukemansu Mountain Pass in OSM, and a zig-zagging road approaching the gap. However, the road stops abruptly upon reaching the beginning of the pass, making it an unlikely location for a connection.

Contributor Note

This report was made possible through the contribution of GDIL's undergraduate researchers: Gunnison Hays, Nyla Hajj, Beau Chapman, Andrew Paumen, Wyatt Krieg, Suraj Pandit, and Eva White. Additional thanks to LTC Sam Rosenberg for the faculty review.

References

- GDIL chose a five square kilometer area because the area's size overlapped with the relative depiction of Aqdarya oil field (marked in green) on Figure 9.

- GDIL chose a ten square kilometer area because the area's size overlapped with the relative depiction of Bazarkhami and Zamarudsay oil fields (marked in green) on Figure 9.

Apr 02, 2024

Taliban claim that 24 total oil wells are active in the Amu Darya basin.

Taliban Ministry of Mines and Petroleum claimed that 15 wells were currently built in the Kashkari oil field, six in the Angot oil field, and three in the Aqdarya oil field, amounting to a total of 24 active wells in the entire Afghan-controlled Amu Darya basin.Source: Ariana News

Feb 21, 2024

Taliban report no commencement on Mes Aynak mining, citing preservation of Buddhist artifacts.

The Taliban reports that copper extraction had not commenced due to negotiations over the preservation and potential transfer of Buddhist and other historical artifacts in the area.Source: TOLONews

Jan 16, 2024

Taliban announce completion of a road connection to the Sino-Afghan border via the Wakhan corridor

Oct 13, 2023

Collected imagery shows signs of early construction efforts at the Chinatown Industrial Park

Photos posted by Yu Minghui of construction progress on the Chinatown Industrial Park. The images show the progression of a single building from August to October 2023. No other buildings are observed to have been constructed or reported on business sites.Jul 08, 2023

Inauguration ceremony held at Kashkari Oil Field.

The inauguration ceremony for the commencement of work by AfgChin was held at Kashkari Oil Field. Taliban Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs Abdul Ghani Baradar and at least one Chinese engineer were in attendance.Source: Ariana News

Jan 06, 2023

CAPEIC acquires three oil blocks in northern Afghanistan.

Xinjiang Central Asia Petroleum and Gas Company (CAPEIC) signs a deal with the Taliban to extract oil from the Amu Darya Basin in northern Afghanistan.Source: Voice of America

Jul 18, 2022

Afghan minister meets with representatives of the MCC-JCL consortium to discuss developments at the Mes Aynak Site.

Source: Global Times

Apr 28, 2022

Taliban approve the "Chinatown industrial park project."

Taliban signs agreement with local Chinese entrepreneurs to build a Chinese industrial park northeast of Kabul, with the intention of it becoming a Special Economic Zone (SEZ).Source: Global Times

Apr 03, 2022

Taliban delegation visit China to meet with MCC officials regarding Mes Aynak.

An IEA delegation visits China and held talks with officials of MCC to indicate their readiness to resume operations at Mes Aynak and reach an agreement.Source: TOLONews

Dec 13, 2021

Taliban express interest in resuming operations at Mes Aynak.

The newly established Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), headed by the Taliban, express interest in MCC-JCL resuming operations on the Mes Aynak Copper Mine site after over ten years of inactivity.Source: ToloNews

Aug 07, 2019

Tourist reporting notes survey and construction crews doing work on a road connecting Sarhad to Wakhjir Pass.

Source: On The Way Around

Jan 04, 2019

Sar-e-pul province claims eight oil wells in Kashkari oil block are active.

In 2019, the Sar-e-Pul provincial government claimed that eight wells in the Kashkari Block were active and generating revenue for the Afghan government. Still, Taliban fighting in the region threatened the wells' operation.Source: Reuters News

Jan 01, 2019

Chinatown Kabul building is constructed

‘China Town Kabul’ was built in 2019 to attract and host foreign investors.Aug 19, 2013

Amu Darya Basin Oil Extraction Operation Halted.

CNPC halts work at Kashkari Oil Field and is “thrown out” due to delays in signing a transit agreement with Uzbekistan.Source: Tolo News

Dec 26, 2011

CNPC signs deal to extract oil in Amu Darya Basin.

China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) inked a 25-year deal with the U.S-backed Afghan Government to develop and operate oil extraction infrastructure in the Amu Darya Basin.Source: Reuters

Apr 08, 2008

Mes Aynak Contract Signed

Two Chinese state-owned enterprises, China Metallurgical Group Cooperation (MCC) and Jiangxi Cooper Company Limited (JCL), sign a $3 billion agreement with the U.S.-backed Afghan government to acquire a 30-year lease to the Mes Aynak site.Source: The China Project

Look Ahead

Imagery analysts should continue examining the Mes Aynak Copper Mine and Amu Darya Basin for new extraction infrastructure. While progress on a Sino-Afghan road-link and an overseas Chinese industrial park is slow, policymakers should consider new momentum in these projects as a sign of China putting more economic weight into the Sino-Afghan relationship.

Things to Watch

- When will Mes Aynak commence copper mining? Will new infrastructure be added to transport copper offsite?

- Will more oil wells be constructed in the Amu Darya oil blocks?

- Will the Afghanistan Chinatown Industrial Park become officially recognized as a Belt and Road project?

- Will the Taliban successfully pave the "little" Pamir highway over in asphalt?

About The Authors

Undergraduate Student at The University of Texas, Task Team Leader at the Global Disinformation Lab

Undergraduate Student at the University of Texas, Research Assistant at the Global (Dis)Information Lab

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.