Overview

The People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) has garnered significant attention with respect to the construction of over three hundred missile silos dispersed across three silo fields. This report seeks to investigate the geospatial characteristics of each site and use that data to inform a search strategy. China watchers and analysts should have a systematic method for defining search strategies, and this report serves as a foundational first step in that effort.

Based on the size of the delivery system(s) the PLARF is installing, this article investigates the depth of bedrock, slope of the terrain, land cover, and proximity to rail transit as suitable geospatial characteristics for silo field locations.

Activity

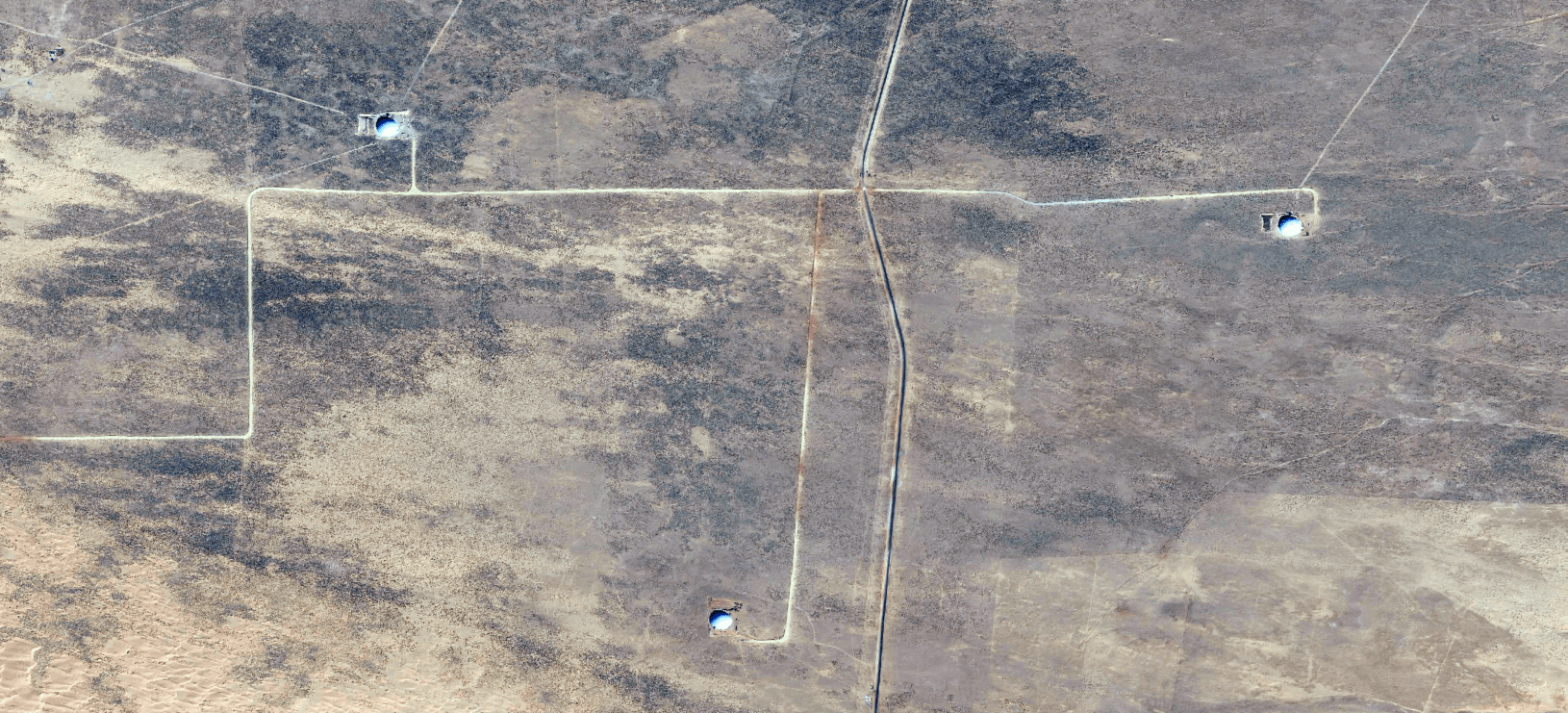

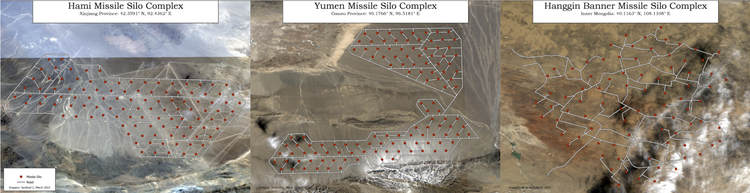

To accomplish the goals stated above, analysis was conducted on three missile complexes that are currently under development in Hami, Yumen, and Hanggin Banner, with the purpose of quantifying each variable mentioned above and leveraging that data to exclude regions that did not meet the criteria for rapid silo construction. Between the three silo complexes, there are currently 319 silos in various stages of completion. This report highlights eight sites that meet or exceed the criteria for silo construction.

Key Intelligence Questions

How many missile silos have been constructed by the People's Liberation Rocket Force? What are the geospatial characteristics of each silo field, and how might those attributes inform a broader search strategy?

Key Judgments

The development of silo fields at Hami, Yumen, and Hanggin Banner will continue to have a significant geopolitical impact and add strain to the international community's relationship with China - specifically the United States and India. A systematic method to identify future silo field construction and collection efforts will improve future geospatial discoveries.

Background

China and Weapons of Mass Destruction

The People's Republic of China (PRC) has been developing, producing, and testing nuclear weapons technology since the First Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1954-1955 and tested its first nuclear weapon in 1964. The live testing continued until 1997 when the PRC entered the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. The current number of PRC nuclear weapons is unknown, but the most recent estimate in 2015 by the Federation of American Scientists places the arsenal at roughly 350 warheads.1 If this estimate is correct, it would give the PRC the fourth largest nuclear arsenal among the five nuclear weapon states acknowledged by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

In 2011, the PRC published a paper that repeated its nuclear policies of maintaining a minimum deterrence strategy with a no-first-use pledge.2 The PRC has not defined what a minimum deterrence policy means, however. Recent People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) deployments such as expansive silo complexes, solid-fueled Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (DF-41), Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (DF-26), and developments such as hypersonic delivery vehicles (DF-ZF) are incongruous at best and ominous at worst.

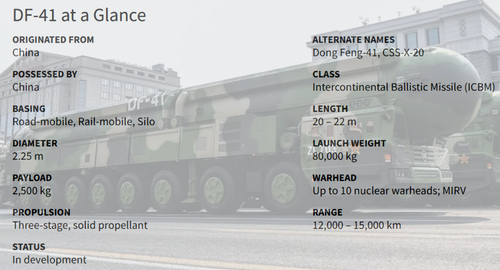

In 2015, reports indicated that the PRC was retrofitting the road-mobile DF-41 to rail-mobile and silo-based launching platforms.3 Five years later, the Federation of American Scientists reported that PLARF was in fact building the silo fields at Hami and Yumen for the DF-41.4 Based on this open-source reporting, this report uses the dimensions of the DF-41 below as one of the factors to prioritize search regions.5 A key assumption will be a minimum bedrock depth of 25 meters, based on the length of the DF-41 (20-22 meters).

Framing the Discussion

What are China's motivations, and how do they fit into an overall strategy?

Experts in and outside of government have questioned China's publicly stated minimum deterrence policy and no-first-use pledge. China will not achieve nuclear parity with Russia or the United States in the near future, but its documented actions show an increase in development and production of its delivery systems, and by inference, an increase in its stockpile. Whether China seeks parity or superiority is not yet clear, but it is on a comprehensive path that would challenge Russian and US positions.

China's ramp-up of its nuclear weapons stockpile and increasingly sophisticated delivery systems is nothing new with respect to the modern geopolitical arena. The Soviet Union created a similar climate during The Cold War with the net effect of mutually assured destruction. China may be breathing new life into the international relations theory known as the stability-instability paradox.6 The United States still has a significant advantage in this challenge due to ballistic missile submarines (SSBN), but China can still create a state of mutually assured destruction by constructing hundreds of missile silos and building out a SSBN fleet. This contemporary application of the stability-instability paradox could allow China to pursue "minor" conventional actions around the world.

Cause for US Concern

After the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, the Intelligence Community set major organizational changes in motion to best position themselves for the growing geopolitical threat faced by a more aggressive Beijing.7 The US is particularly concerned about maritime travel in the South China Sea, a kinetic conflict on the Korean Peninsula, and President Xi's public desire to unify China by bringing Taiwan back under Beijing's control. If the United States finds itself in a situation resembling the Cold War with China, then the PRC could feel emboldened to pursue a proxy war or land grab if they assess the risk of a direct conflict with the United States as highly improbable.

These developments must play out in the public arena so the US may have the political capital to bring Beijing to the negotiating table to seriously discuss nuclear disarmament similar to the START treaties with the former Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. Certain Pentagon officials are also concerned that China may be pivoting away from its long-stated no-first-use policy declaration, but dissenters argue that the expansion of silo-based systems intends to safeguard the survivability of its retaliatory nuclear forces. Either way, STRATCOM's recent testimony to Congress suggests that it sees recent developments as destabilizing.8

To fully assess the China threat, it is also necessary to consider the capability of the associated delivery system, command and control, readiness, posture, doctrine, and training. By these measures, China is already capable of executing any plausible nuclear employment strategy within their region and will soon be able to do so at intercontinental ranges. As Admiral Charles Richard, STRATCOM Commander wrote in a statement to the United States Senate Committee on Armed Services on April 20, 2021, "they are no longer a 'lesser included case' of the pacing nuclear threat, Russia."

Analysis Factors

Objective

This study collected data on the geospatial characteristics of the recently developed silo complexes and identified regions that satisfied the requirements for rapid silo field construction. The focus of this study's geospatial characterization and analysis was only on a subset (Hami/Yumen/Hanggin Banner9) of ICBM sites within China and not any other types of ICBM or ballistic missile sites. While the construction of nuclear silos is very labor-intensive, the one factor that severely impacts the time-to-completion is the depth of bedrock. PLARF has been able to surprise many China watchers with its ability to rapidly construct silo fields. This accelerated time-to-completion may have been possible by choosing areas with a bedrock depth suitable for rapid excavation. The variables introduced below inform the identification of candidate regions that could prioritize future open analytic and collection efforts in order to quickly identify the construction of additional silo fields.

Transportation Networks

Considering the silo components, manpower, relevant equipment, and raw materials, the construction of one silo, let alone over three hundred, requires a significant amount of infrastructure. The People's Liberation Army (PLA) was originally tasked with building out the railway system across the country. That responsibility was transferred to the China Railway Construction Corporation in 1984, but they continued to maintain a strong relationship with the PLA.10 Since then, the PRC has made significant investments in railroads throughout the country but with an emphasis on the more densely populated eastern part of China. During the Cold War, the Strategic Rocket Forces of the Soviet Union largely constructed missile bases within 40-65 kilometers of the railroad. As it relates to China, this becomes a reasonable assumption and use case for formulating a search strategy. The Soviets did not build massive fields in one location as the Chinese have done, but for the purposes of this study, the rail proximity assumption is reasonable due to China's overall use of rail more broadly throughout the country. Very little detailed and specific open GIS data exists on railroads in China, but the best open-source data stated the rail lines used are used for both passengers and freight11. While it may make more sense to only include dedicated freight-rail lines, there is no discernible difference between the two classifications within the open data available. Therefore, each rail line was treated with equal weight.

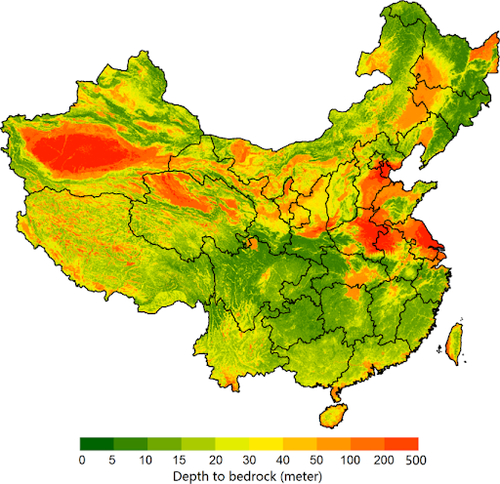

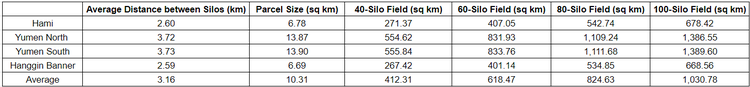

Depth to Bedrock

Little original geospatial data exists on bedrock depth in China, but researchers from Scientific Data used borehole samples from the Chinese National Important Geological Borehole Database to reason about this metric.12 They devised a sampling scheme of 6,382 Depth to Bedrock (DTB) observations spread throughout mainland China and used that data to create a country-wide raster layer. The figure below is a map of the final product, which is a 100-meter resolution raster layer that provides the predicted bedrock depth measured in meters. This layer was critical for characterizing existing silo locations and calculating statistics like the mean depth to bedrock for the Hami, Yumen, and Hanggin Banner silo fields. This layer also served as a core dataset for forecasting the locations of potential silo fields based on the hypothesis that these fields require a depth of 25 meters to accommodate the 20-22 meter length of an ICBM such as the DF-41 with additional space for the silo's overall construction.

Land Cover & Slope

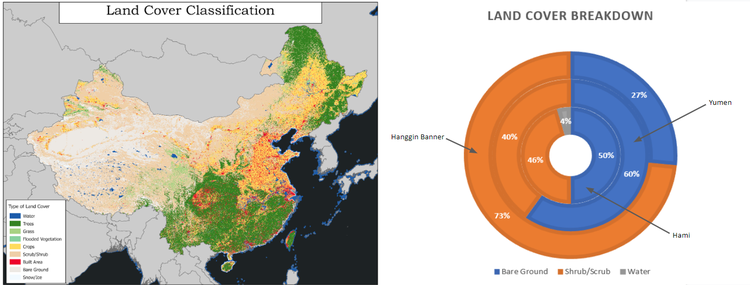

As part of the Living Atlas collection, ESRI developed a 10-meter resolution land cover/land use raster layer that has up-to-date global coverage, serving as another key down-selection variable in the search strategy. Only two land cover types were present at Hami, Yumen, and Hanggin Banner: bare ground and shrub/scrub. The graphics below depict the various land cover types throughout China as well as a classification breakdown of each missile complex.

A Digital Elevation Model was created to interpolate surface slope at a 500-meter resolution. The Chinese have been building these silo fields in locations with bare ground and minimal surface slope. The slope distribution of all three silo fields reported a max value of 1.48 degrees, which narrowed the scope to raster tiles with a slope less than or equal to two degrees.

Methodology

Tools Used

ESRI's ArcGIS Pro software was used for all GIS analysis. The specific tools used within ArcGIS will be named and usage will be explained for reproducibility and transparency.

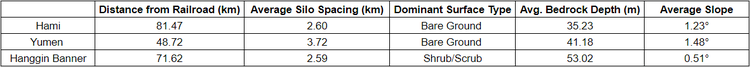

Geospatial Characteristics

A methodical approach was needed to mitigate the risk of removing promising candidate regions. During the Cold War, Soviet silo construction largely depended on proximity to the Trans-Siberian Railway. To quantify that proximity in this study, the "Generate Near Table" tool was used to calculate the nearest distance of each silo field to the railroad from the geographic center of each site. A mean distance of 67 kilometers was observed, and a maximum of 81 kilometers. The maximum value was used to create a buffer around the railway network which was used to remove data that exceeded 81 kilometers from the railway system.

The second question that needed to be addressed was the size of a potential silo field. The "Average Nearest Neighbor" tool was used to calculate the average distance, or spacing, between each individual silo. The Yumen site is distributed across two different locations so Yumen North and Yumen South were treated as independent sections. The configuration of silos within Hami and Yumen appear more "orderly" (see electro-optical overview imagery above) than the configuration of Hanggin Banner but the spacing was similar amongst all three. These values were used to calculate the size of each individual silo parcel, and expand that in intervals of forty, sixty, eighty, and one hundred silos. The table below highlights the size of a parcel for a single silo at each missile complex, and the estimated square kilometers of a prospective facility which will inform candidate selection in the results.

Leveraging Geospatial Characteristics to make Down-selections

Each of the previous steps led to significant down-selections to the raw raster files. All three rasters were different resolutions, which if not properly mitigated, would have dramatically impacted the integrity of the results. Prior to making down-selections, the higher resolution bedrock and land cover raster layers were down-sampled and aligned with the 500-meter resolution slope layer so each raster tile could be analyzed independently.

For each layer, the "Extract by Mask" tool was used to only select raster tiles that were within the railroad buffer polygon. The "Set Null" tool was then used to assign "NoData" to each raster tile that did not meet the bedrock depth, land cover, and slope requirements listed above. The graphic below reflects the first stage of analysis concerning bedrock depth, and demonstrates how effective it can be as a down-selection variable. The bedrock, slope, and land-cover layers were aggregated and filtered based on the following minimum conditions for silo construction:

- Bedrock depth greater than 25 meters

- Average surface slope less than 2 degrees

- Land cover that was either bare ground or shrub/scrub

Results

Locate Regions Tool

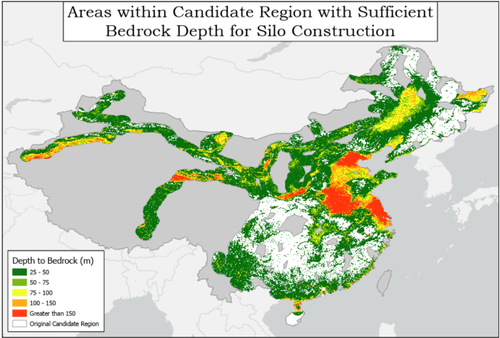

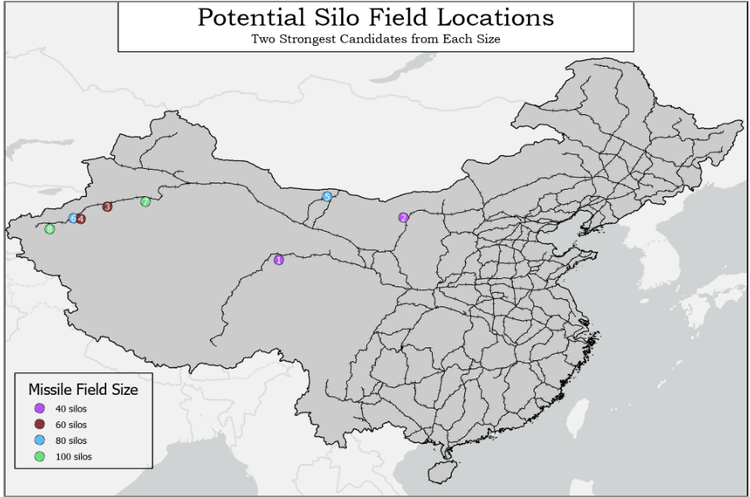

The purpose of manipulating and combining these raster files was to programmatically locate regions that are suitable for silo construction. The "Locate Regions" was used due to its capability of identifying the most suitable regions, or groups of contiguous raster cells, from an input raster that satisfies a specified evaluation criterion that meets a specific shape and size constraint. The evaluation criteria included the depth to bedrock and the size of a prospective silo field based on the estimated square kilometers required for complexes with forty, sixty, eighty, and one-hundred silos. The intent was to select two prospective silo fields for each size (40/60/80/100 silos) that would accommodate rapid construction, thus the two sites with the highest average bedrock depth were chosen.

High-Level Results

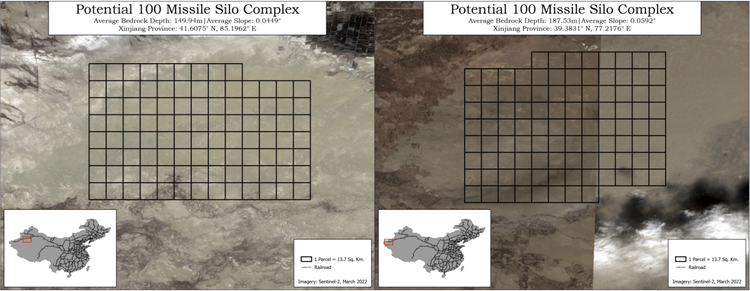

As shown in the map above, the net result was eight candidates of varying size that were predicted to be strong candidates for future construction based on the heuristics covered in the Analysis Factors section. The majority of the sites were located in Western China because that area consisted of flat bare ground, and most importantly, had very deep bedrock relative to the rest of the country. Each candidate is depicted in the imagery below along with metrics related to each parcel's geological characteristics including average bedrock depth and average slope.

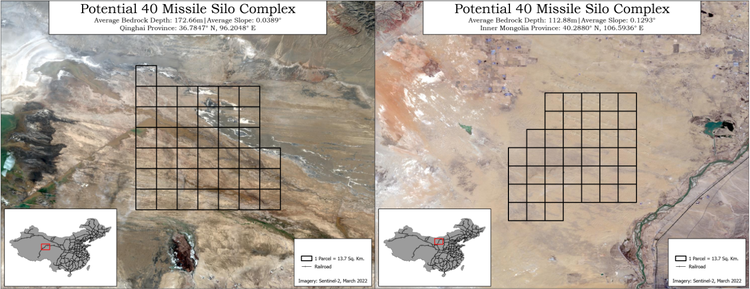

40 Silo Installations

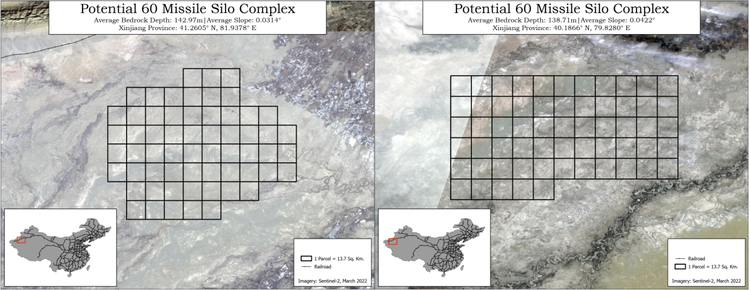

60 Silo Installations

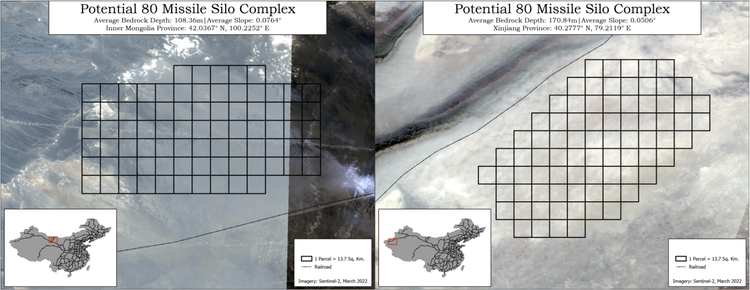

80 Silo Installations

100 Silo Installations

Future Work

Shortcoming of Analysis

A key assumption in this report was that the Chinese would almost exclusively use their railway network instead of major roads to transport materials, missiles, and heavy construction equipment. Open literature shows that China has a robust highway system, yet there is little to no literature on the silo construction process in China. Due to the lack of specific information regarding the construction process and requirements, the 25-meter minimum was chosen based on the estimated 20-22 meter length of the DF-41. The PLA has a road-mobile version of the DF-4114 that could transport the delivery systems to a silo field, but it is the author's position that the construction process would still depend on railroads to construct a silo installation of this size. Moreover, this study assumed that the construction process would depend on rail proximity as in the Soviet Union.

A large portion of southwestern China with limited railway transit was excluded, but depth to bedrock and the amount of bare ground would make it a strong candidate for silo field construction. There are also several major railroad connections under construction in the Western part of the country.15 Researchers should monitor the construction of these rail lines as they could be dually used by the PLA.

Works Cited

- Hans M. Kristensen & Robert S. Norris (2011) Chinese nuclear forces, 2011, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 67:6, 81-87, DOI: 10.1177/0096340211426630

- "China Publishes White Paper on Arms Control". China.org.cn. September 1, 2005. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- Gady, F.-S. (2016, January 5). China tests new rail-mobile missile capable of hitting all of US. The Diplomat. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://thediplomat.com/2016/01/china-tests-new-rail-mobile-missile-capable-of-hitting-all-of-us/.

- Korda, M., & Kristensen, H. (2021, July 26). China Is Building A Second Nuclear Missile Silo Field. Federation Of American Scientists. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://fas.org/blogs/security/2021/07/china-is-building-a-second-nuclear-missile-silo-field/.

- Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2021, July 31). DF-41 (Dong Feng-41 / CSS-X-20). Missile Threat. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/df-41/.

- Kapur, S. (2017). Stability-instability paradox. In F. Moghaddam (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of political behavior (pp. 799-801). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://www.doi.org/10.4135/9781483391144.n364f

- Barnes, J. E. (2021, October 7). C.I.A. Reorganization to Place New Focus on China. The New York Times. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/07/us/politics/cia-reorganization-china.html.

- Kristensen, H. M., &F Korda, M. (2021, September 1). China's nuclear missile silo expansion: From minimum deterrence to medium deterrence. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://thebulletin.org/2021/09/chinas-nuclear-missile-silo-expansion-from-minimum-deterrence-to-medium-deterrence/.

- Lee, R. (2021, August 12). PLA Likely Begins Construction of an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Silo Site near Hanggin Banner. Air University (AU). Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/CASI/Display/Article/2729781/pla-likely-begins-construction-of-an-intercontinental-ballistic-missile-silo-si/

- Dorfman, Z., & Allen-Ebrahimian, B. (2020, June 24). Defense Department produces list of Chinese military-linked companies. Axios. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.axios.com/defense-department-chinese-military-linked-companies-856b9315-48d2-4aec-b932-97b8f29a4d40.html

- Li, Yifan, 2016, "China High Speed Railways and Stations (2016)", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JIISNB, Harvard Dataverse, V1

- Yan, F., Shangguan, W., Zhang, J. et al. Depth-to-bedrock map of China at a spatial resolution of 100 meters. Sci Data 7, 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0345-6.

- Kristensen, H. (n.d.). Chinese Missile Facilities. Missile Facilities - China Nuclear Forces. Retrieved September 12, 2021, from https://nuke.fas.org/guide/china/facility/missile.htm

- Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China 2021 (PDF). Office of the Secretary of Defense (Report). U.S. Department of Defense. 2021. p. 91

- China Railway Map. (2021). Travel China Guide. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.travelchinaguide.com/images/map/railway.jpg.

Look Ahead

Given the recent democratization of high-resolution commercial electro-optical and radar imagery, readers can expect more analyses on these missile complexes to be available in the public domain. This down-selection analysis can help others using open and commercial sources better understand China's missile programs.

Things to Watch

- The layouts at Hami and Yumen appear to follow some pattern. Is there a reason why the silos at Hanggin Banner do not follow that pattern?

- Does the development of these missile complexes indicate a change in China's nuclear doctrine?

About The Authors

Johns Hopkins University, M.S. Geospatial Intelligence

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.