Overview

Latest: In accordance with planned infrastructure construction and improvement, both China and Russia increased land transportation capabilities across all border crossings, creating a net positive change in road and rail capacity.

Impact: The improvements to cross-border infrastructure and increased border traffic demonstrate Chinese-Russian commitments to increase economy ties. However, the full economic impact on both countries is unknown. Furthermore, Russian economic and foreign policy continue to favor expanded trade with China due to negative impacts from the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war.

Activity

Economic activity likely increased along the China-Russia border at nine established crossings from January 2020 to December 2024, based on significant development of road-based infrastructure. China demonstrated steady development pace overall, with three crossings—Dongning, Manzhouli, and Suifenhe— showing an average of a 231% increase in truck traffic, with an additional two crossings, Heihe and Hunchun, expanding their facilities to accommodate growing trade. Russian development was more gradual, with a 156% change in traffic at two locations, Poltavka and Blagoveshchensk. Rail infrastructure remained mostly unchanged, except for the expansion at the Russian municipality of Nizhneleninskoye. Future border developments will likely depend on shifting geopolitical and economic factors, as proposed additions to existing crossings and the creation of new crossings are uncertain.

Background

China-Russia Land Border Crossings

Between China and Russia, there are only nine border crossings, all of which are located between northeastern China and southeastern Russia; this is despite the China-Russia border spanning over 2,600 miles.https://www.cfr.org/article/where-china-russia-partnership-headed-seven-charts-and-maps[1] Though there are mountain passes between northwestern China and south-central Russia, these are impossible to cross with vehicles.

Five of the border crossings solely incorporate roads, while the remaining four crossings have both roads and railroads, providing two mechanisms for both passengers and cargo to cross at. There are no border crossings that are solely via rail. All nine border crossings were identified using the Chinese government’s website listing ports of entry.https://www.caop.org.cn/[2]

Land Border Crossings

| Location Name | Road / Road & Rail Status |

|---|---|

| Dongning, China – Poltavka, Russia | Road |

| Heihe, China – Blagoveshchensk, Russia | Road |

| Hulin, China – Markovo, Russia | Road |

| Hunchun, China – Kraskino, Russia | Road & Rail |

| Manzhouli, China – Zabaykalsk, Russia | Road & Rail |

| Mishan, China – Turiy Rog, Russia | Road |

| Shiwei, China – Olochi, Russia | Road |

| Suifenhe, China – Pogranichny, Russia | Road & Rail |

| Tongjiang, China – Nizhneleninskoye, Russia | Road & Rail |

Rail gauge interoperability

China uses a 1435 mm standard gauge, whereas Russia uses a 1520 mm broad gauge. On the Chinese side of the Sino-Russian rail border crossing are large transshipment or bogie exchange facilities. The purpose of these facilities is to handle conversion of rail cars to overcome the gauge differences. The presence of these facilities indicate China has invested significantly in infrastructure to handle the gauge disparity, while Russia appears to lack many of the same facilities and infrastructure at the same border crossings. Thus, Chinese goods crossing into Russia must change tracks upon crossing the border, whereas Russian goods imported into China can travel further without changing tracks. This creates a disadvantage for Russia, as transporters must spend more time moving cargo from one train to another at internal exchange facilities, delaying travel, and ultimately hindering the cross-border supply chain.

However, it is worth noting that Russian territorial governments as well as Moscow have come forward with announcements to modernize the main lines, spurs, and border crossings to keep up with growing trade demand in the east, particularly from China. This includes the modernization and reconstruction of stations at its various rail crossings at the Chinese-Russian border.

Eastern Polygon rail infrastructures’ current capacity

Russia's eastern rail infrastructure, particularly the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) and the Trans-Siberian Mainline (TSM), is struggling to handle growing freight demand driven by increased trade with Asia-Pacific countries.http://gudok.ru[3] This surge stems from Russia's pivot to eastern markets amid Western sanctions and rising Chinese demand for resources like coal, natural gas, and crops.Ibid[4] However, limited transport capacity, border crossing delays, and infrastructure bottlenecks continue to hinder trade flow.Ibid[5]

However, past, current, and proposed projects aim to minimize bottlenecks (such as the reconstruction of the Skovorodino-Reinovo railway and the Dzhalinda-Mohe rail bridge) and resolve issues with operating limits on existing mainlines and infrastructure such as the BAM, TSM, and lines connecting the main lines to China.Ibid[6] Additionally, it is important to note that “calculations show that the growing capacity will still not keep up with the growth in demand,” with Yakutia officials calling for a “radical solution to the problem.”Ibid[7]

In December of 2022, the Russian government directed Russian Railways to prioritize container trains for coal exports to the Far Eastern Federal District, adding three container trains per day.http://ng.ru[8] However, the addition of trains was insufficient to add enough capacity to fulfill coal export contracts, thus, checkpoint delays mainly impacted imports from China.Ibid[9] According to Surana Radnaeva of Sinoruss (a Russian financial company primarily doing business with China), Russia's infrastructure was unprepared for the current surge in trade with China.Ibid[10] Radnaeva stated that the strain not only affects border crossings, but also internal Russian infrastructure.Ibid[11]

The Russian government plans to boost freight capacity on the BAM and TSM from 150 million tons in 2023 to 270 million tons by 2032.https://worldview.stratfor.com/situation-report/russia-government-approves-expansion-bam-trans-siberian-railway[12] However, financial estimates suggest that modernization efforts will likely fall short in the near term, leaving Russia ill-equipped to fully support rising Eastern trade demands.Ibid[13]

It is important to note that as of 2 July 2023, “Almost half of the transport capacity of Russian railways is occupied with the export of coal, which makes it difficult to export goods with higher added value.”gudok.ru[14] There are still obstacles on alternative routes from Russia to China – border crossings for trucks.Ibid[15] The time period for exiting to China through some checkpoints in the Far Eastern Federal District is 20–25 days.Ibid[16]

Ongoing and future projects

Regarding cross-border infrastructure, China and Russia publicly announce their larger-scale projects, with a broad focus on solidifying existing economic and political ties. The following projects involve ongoing development of existing crossings, propositions to develop said crossings, or propositions to create new crossings.

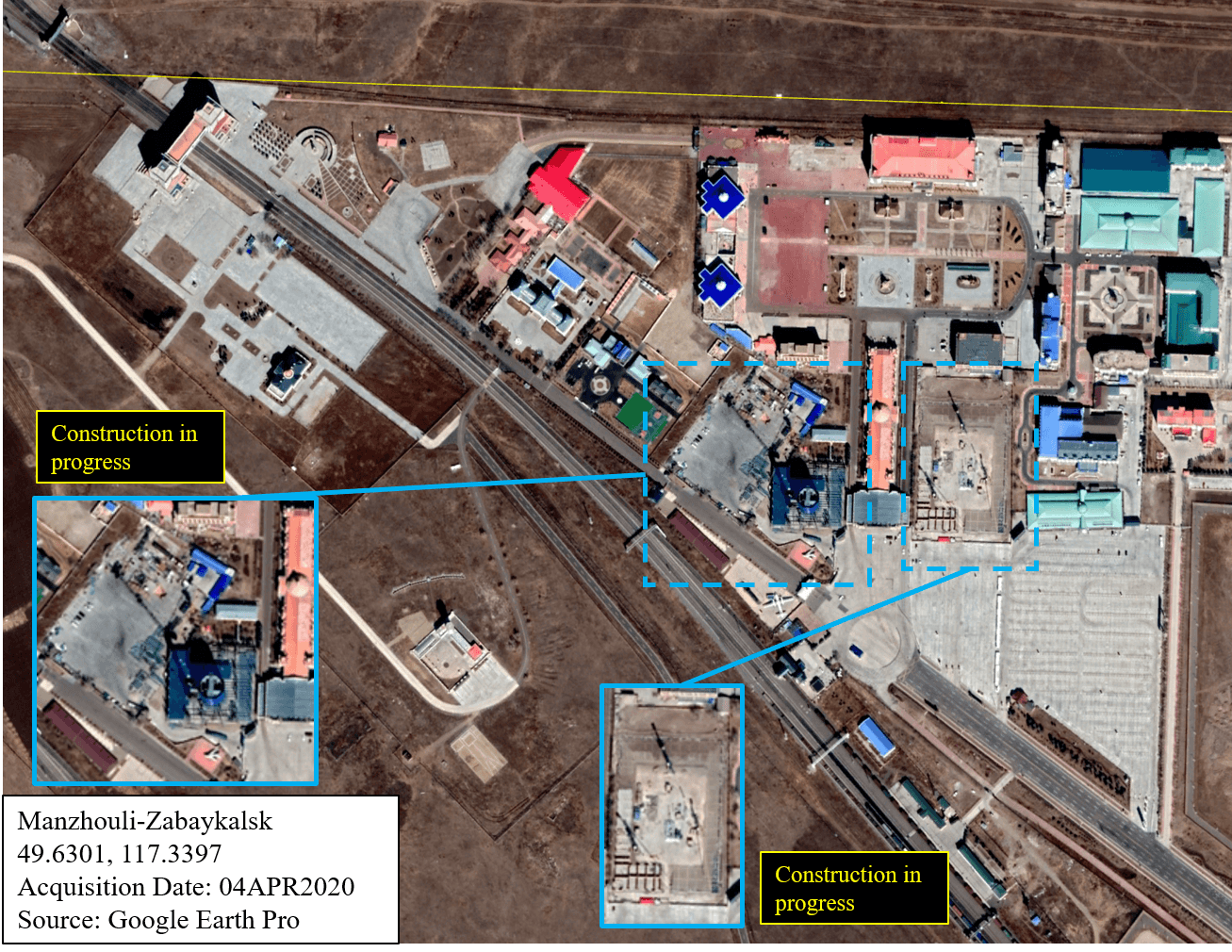

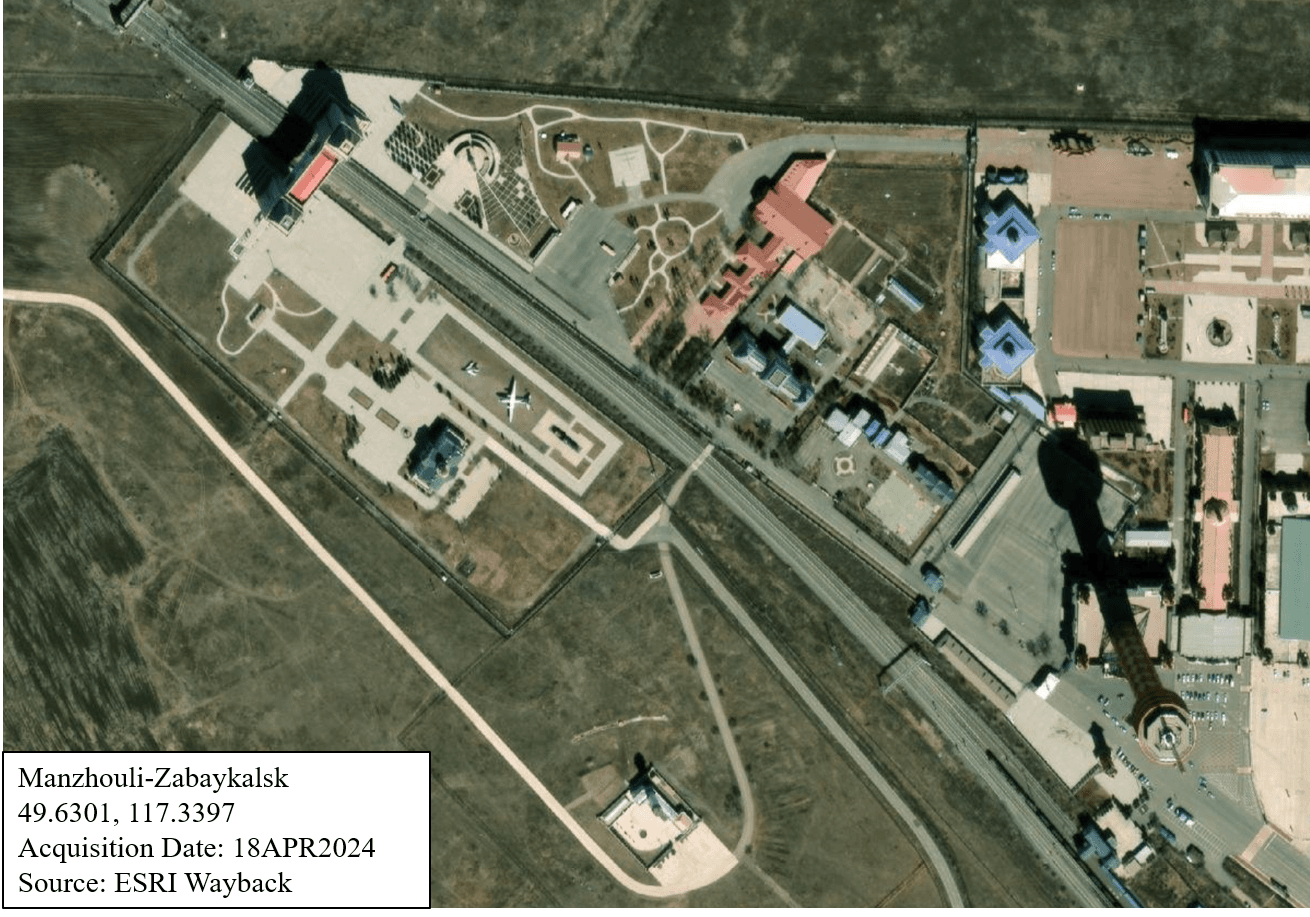

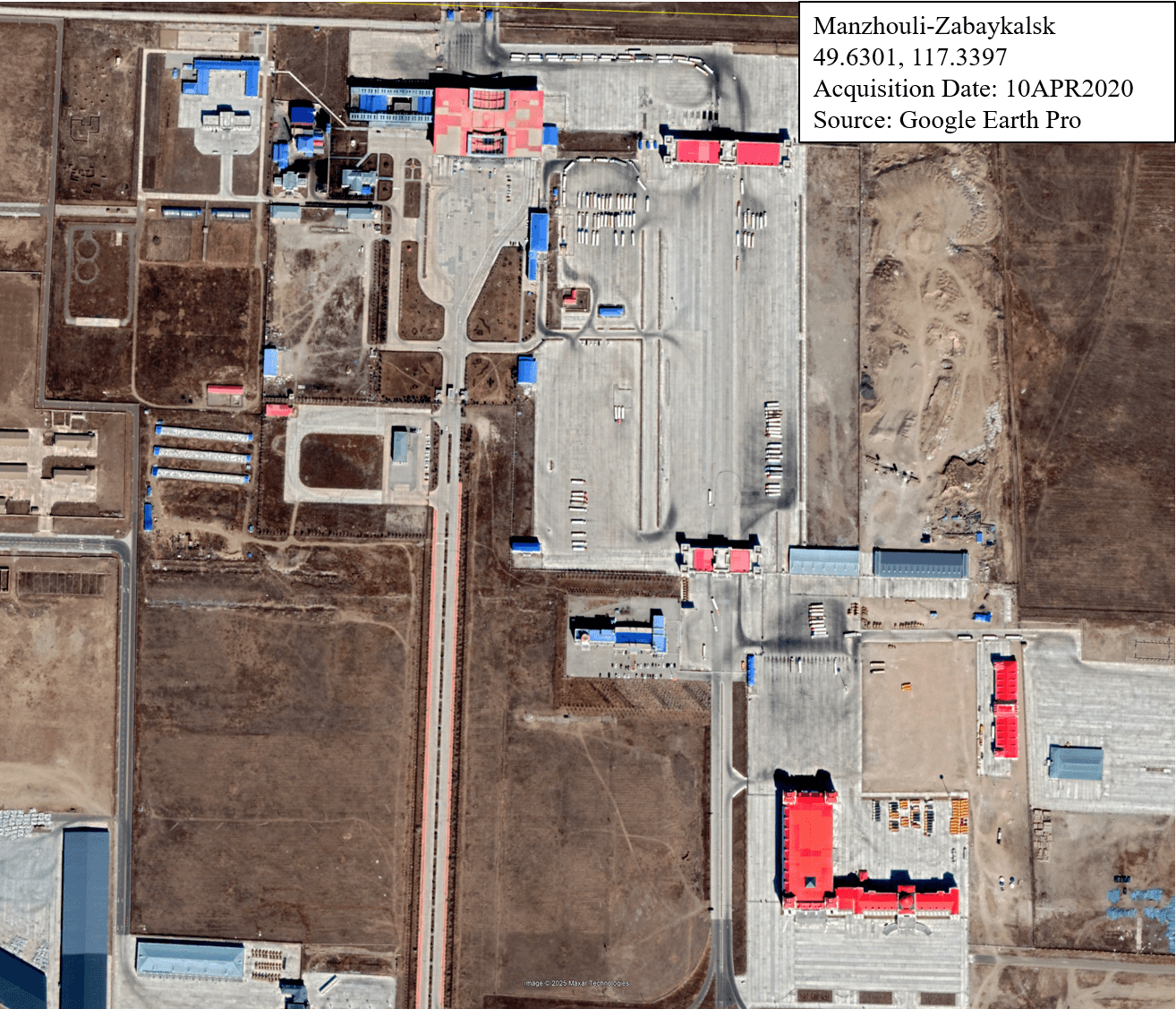

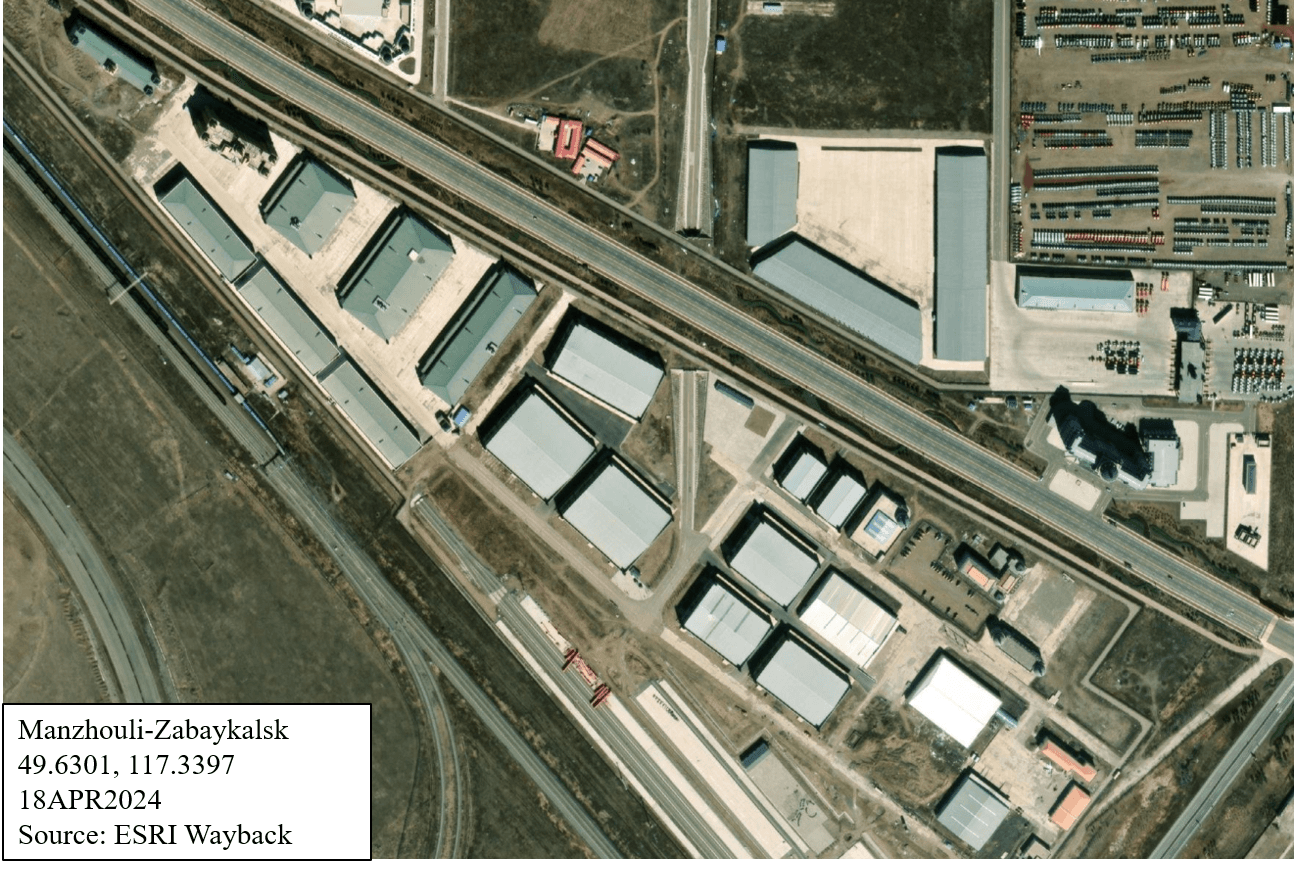

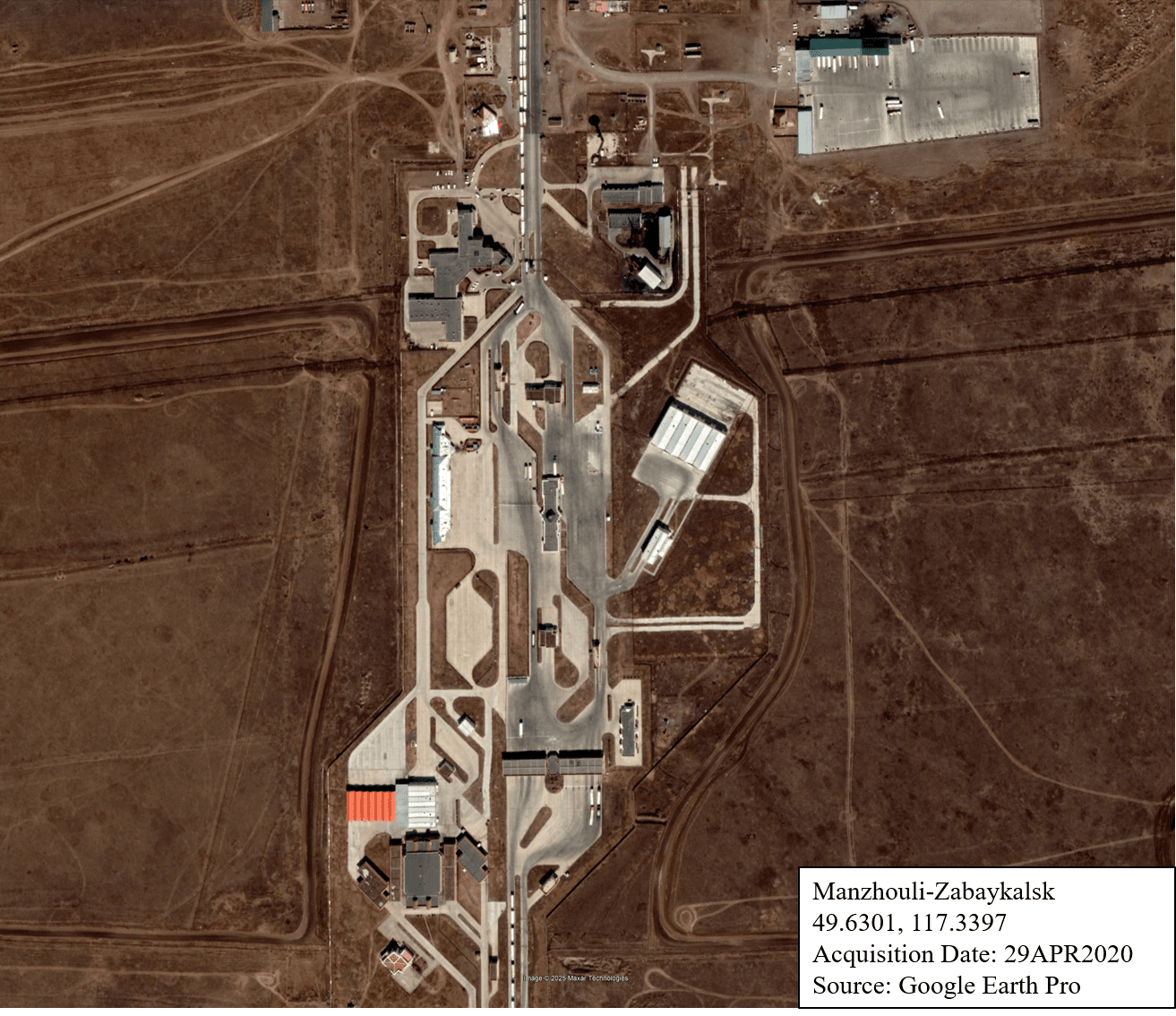

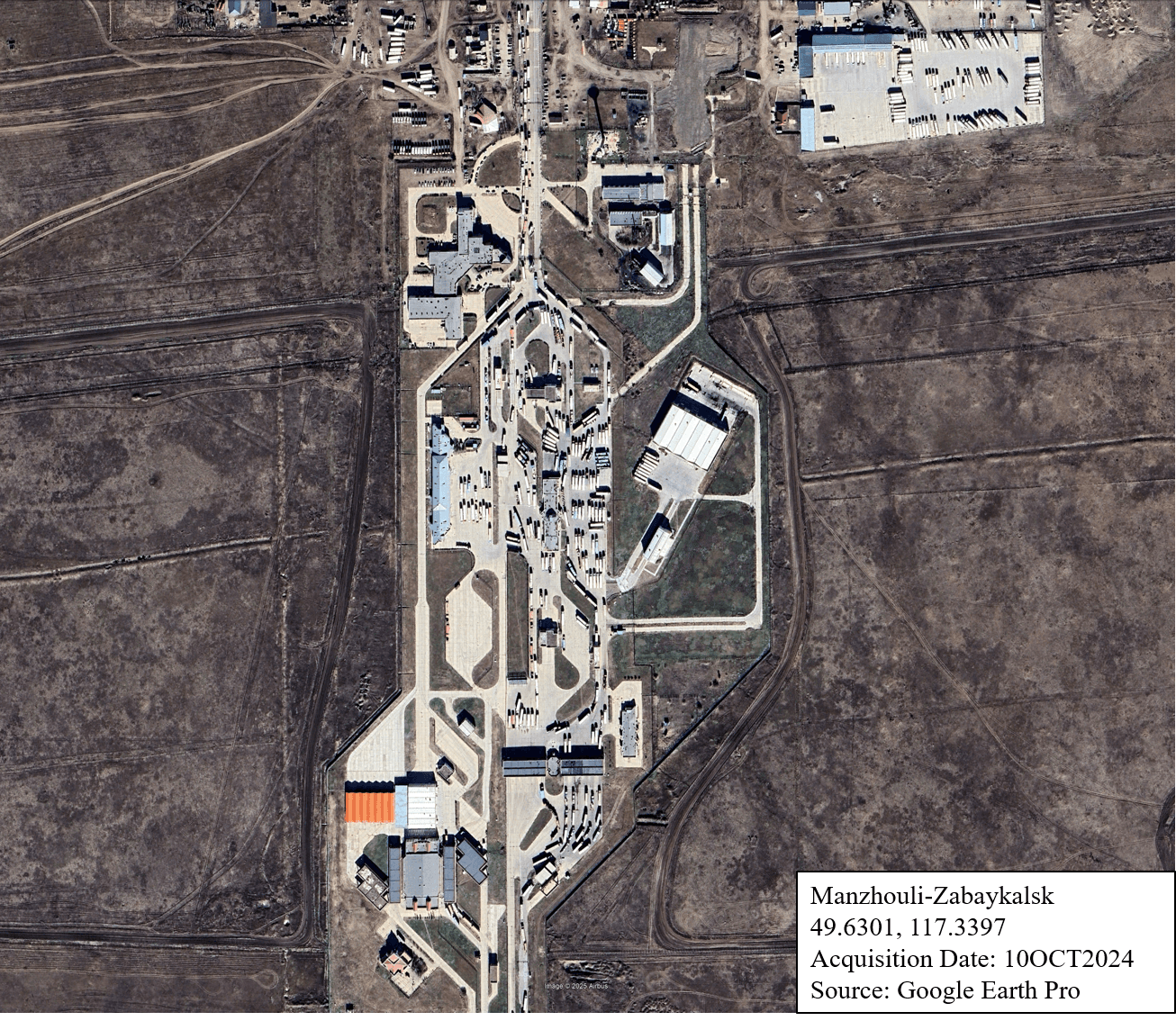

- Manzhouli, China – Zabaykalsk, Russia: In May 2024, China Railway and Russian Railways (both state-owned enterprises) signed a strategic cooperation agreement.https://www.railwaygazette.com/policy/russian-and-chinese-railways-plan-strategic-co-operation/66601.article[17] Under the broader scope of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), this agreement aims to improve existing border crossings, including the Manzhouli-Zabaykalsk location.Ibid[18] Proposed plans include the construction of a new 1435mm-gauge rail track across the border,Ibid[19] as well as a significant increase in road capacity from 18 lanes to 28 lanes, potentially making the crossing the largest and busiest border crossing.https://russiaspivottoasia.com/development-of-the-zabaikalsk-manzhouli-russia-china-border-checkpoint/[20] Furthermore, this agreement aims to boost mail, e-commerce, and agricultural shipments (including meat and grain) via regular container trains.https://www.newsilkroaddiscovery.com/russia-china-speed-up-construction-of-second-railway-line-at-zabaikalsk-manchuria-crossing/[21] Both nations are prepared to handle increased rail traffic while continuing to use existing infrastructure, such as warehouses and terminals.https://russiaspivottoasia.com/development-of-the-zabaikalsk-manzhouli-russia-china-border-checkpoint/[22] The Russian clearance post’s boundaries were expanded to allow customs and tax benefits, with local authorities supporting investment and cost reimbursement.https://russiaspivottoasia.com/new-russian-rail-digital-container-terminal-to-china-being-constructed/[23] Additionally, in 2022, TransContainer, a subsidiary of Delo Group (Russia’s largest transport company), upgraded the Zabaykalsk terminal, increasing capacity to 555,000 containers (in twenty-foot equivalent units, or TEU) annually.http://delo-group.com/[24]

- Tongjiang, China – Nizhneleninskoye, Russia: As of September 2023, Russian intermodal company FESCO and Chinese transport company Margin Group are collaborating on a container terminal near the rail border crossing, with a planned capacity of at least 340,000 TEU per year.prim.rbc.ru[25] Additional projects expected by 2030 include storage facilities for stable gas condensate, petroleum products (including liquefied petroleum gas, or LPG), hazardous cargo handling, and other general imported goods.Ibid[26]

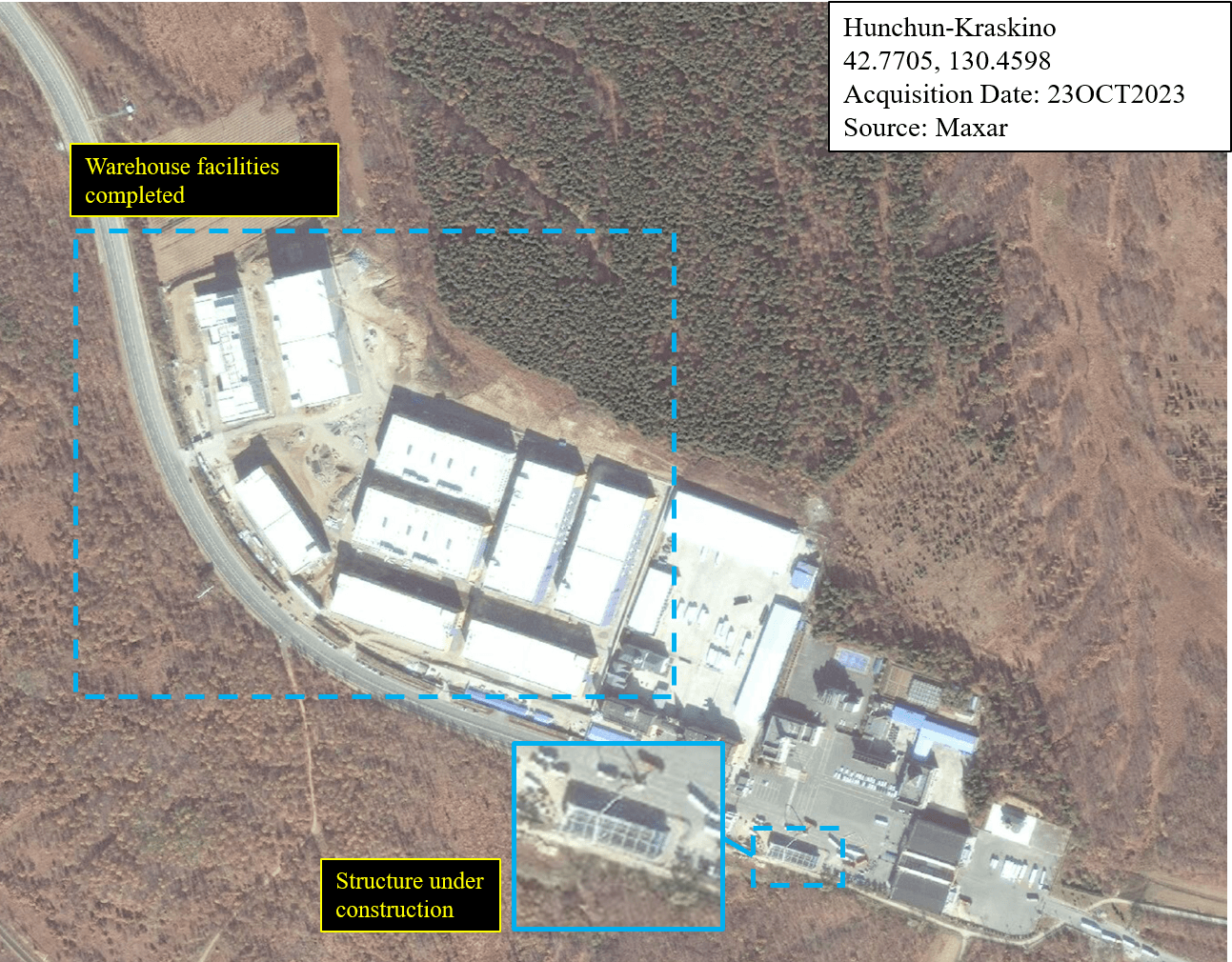

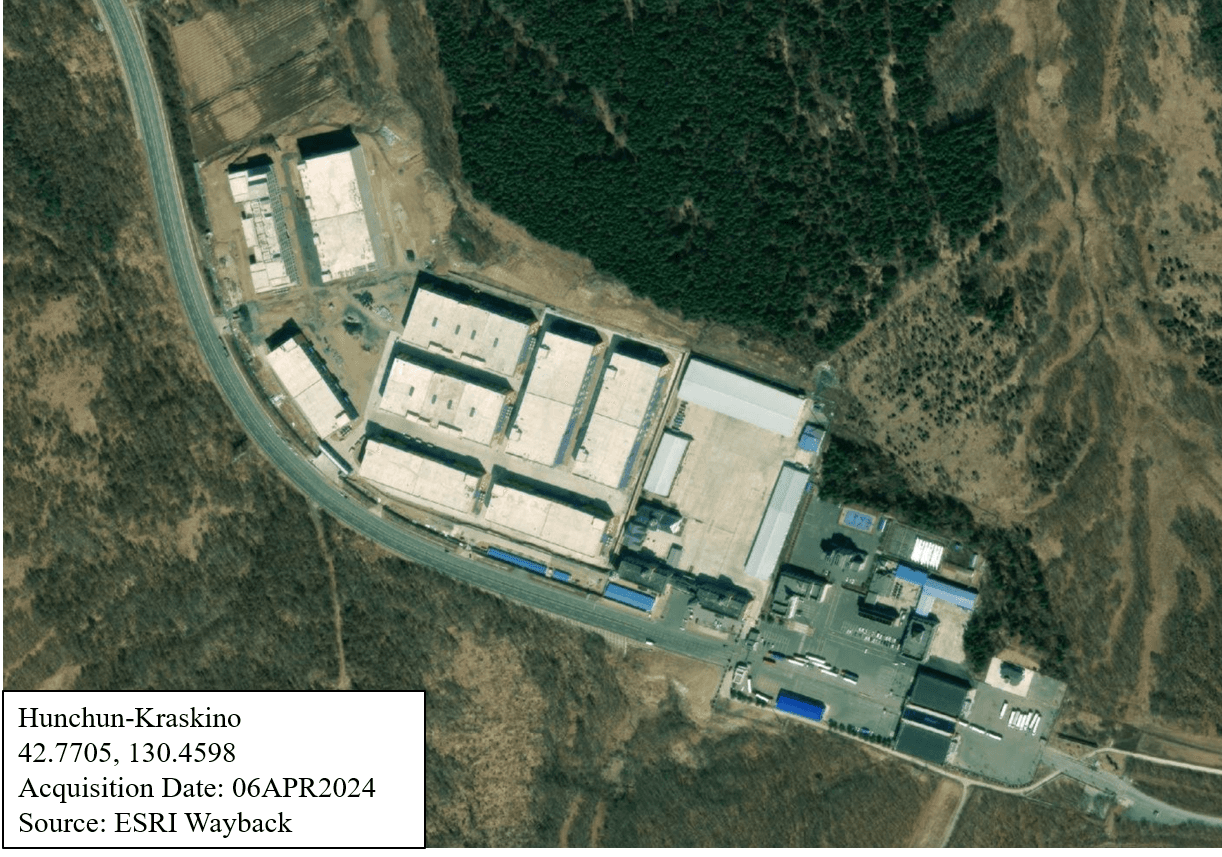

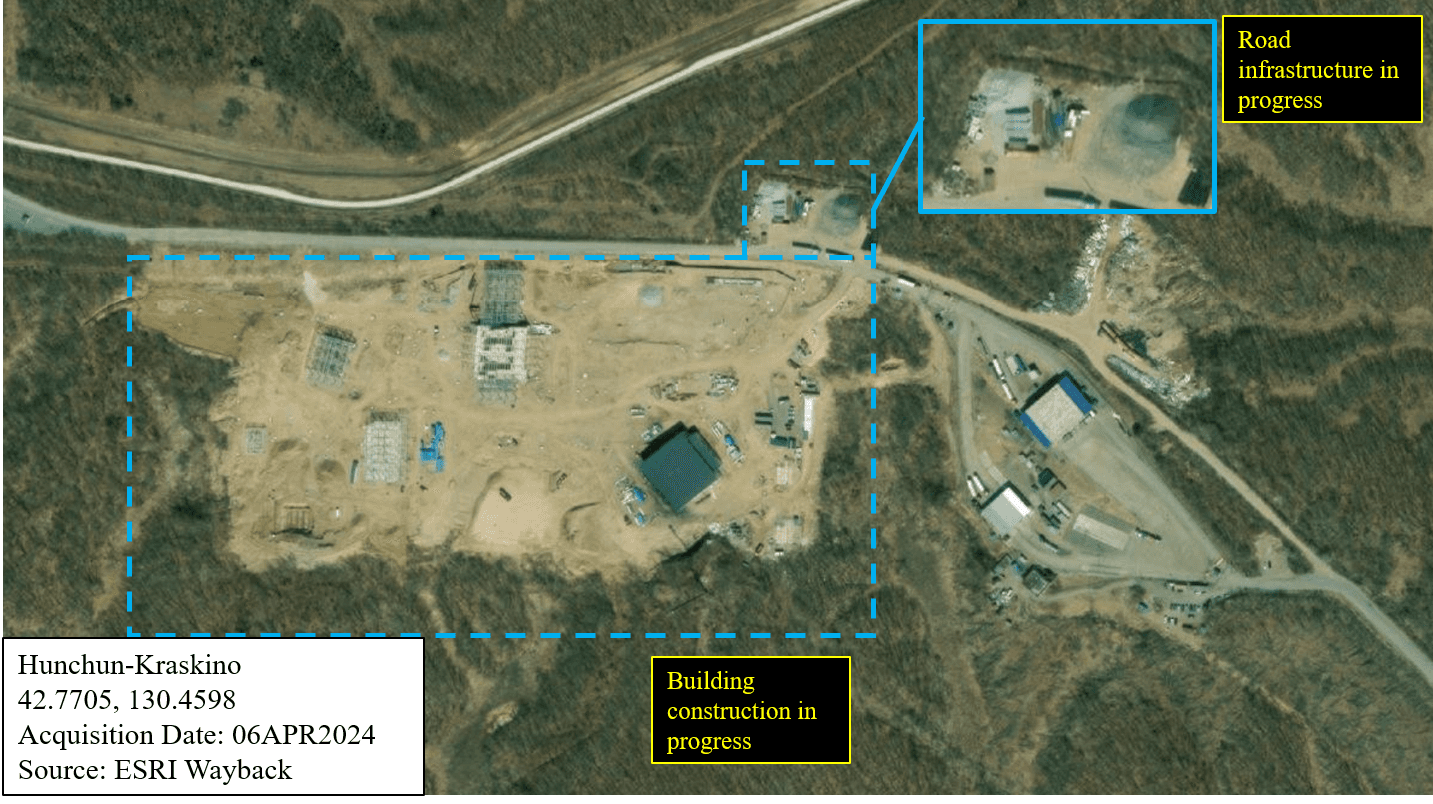

- Hunchun, China – Kraskino, Russia: As of July 2023, a new international logistics terminal is under construction at the Hunchun border crossing, to include an amalgamation of warehouses and workshops.dzen.ru[27] Also, as of September 2023, Russian and Chinese state transport officials discussed the laying of 1435mm track (which is the Chinese standard gauge) in near Kraskino to reduce delays in transferring cargo between trains and causing storage constraints at the border.Ibid[28]

- Mohe, China – Dzhalinda, Russia (proposed): In July 2023, the Chinese government and the Sakha Republic federal subject government agreed to construct a railway connecting the respective cities of Mohe and Dzhalinda.https://www.globalconstructionreview.com/china-and-russia-agree-to-build-second-rail-bridge-over-the-river-amur/[29] A second railway connecting the two countries over the Amur River is also slated to connect the same municipalities.Ibid[30] Although no starting date has been given, the Republic of Sakha Railway Company signed a memorandum of understanding with the China Industry Overseas Development Association to begin construction.Ibid[31]

This new railway can allow Russia to export up to 10 million tons of natural resources, including coal and timber, without relying on Vladivostok’s seaport.Ibid[32] China will primarily fund and construct the project under a concession agreement, broadly granting it long-term access to the region’s resources in exchange for financing the project.https://www.eurasiareview.com/10032023-since-russia-cant-afford-it-china-will-build-railway-north-to-sakha-analysis/[33]

Methods:

Planning

In order to answer the research question of, “From January 2020 to December 2024, what changes, additions, or upgrades have been made to land-based transport infrastructure connecting Russia to China?” the team determined that change in China-Russia land transport infrastructure would be measured by chronologically cataloging activity and construction project status at each border crossing. The following factors formed the basis for this analysis:

- Changes in road-based infrastructure regarding: major highways, entry and exit ramps, interchanges, cargo depots, fuel stations, and border infrastructure. Regarding the latter, this includes inspection points and holding areas for semi-trucks and passenger vehicles.

- Changes in railway-based infrastructure regarding: railway lines and networks, railroad crossings (such as bridges or tunnels), and rail yards, to include cargo depots and fueling stations. Furthermore, this also includes intermodal terminals, where rail transport transitions to road-based transport (primarily semi-trucks), and vice versa. Finally, as with road-based changes, this includes border infrastructure, with inspection points and holding areas for train cars.

Locations were determined based on open-source information on border crossings between China and Russia and confirmed via geospatial analysis. This includes both road and railroad connections, focused on southeastern Russia/northeastern China.

Collection

All available satellite imagery of Russian-Chinese border crossings from Q1 2020 to Q4 2024 was collected from the following sources:

- Google Earth Pro: The team utilized this program as the primary imagery source, given its high-quality and comprehensive temporal collection of imagery. Google Earth Pro is an application that provides historical imagery to the present day; by using the time slider function, one can shift between all available dates. This program compiles imagery from multiple sources, such as US government entities (e.g. NGA, the US Navy, NOAA, NASA) and private entities like Airbus.

- ESRI Wayback: The team utilized this program as a secondary imagery source. Like Google Earth Pro, ESRI Wayback provides historical imagery. One benefit is that using its “Swipe Mode,” one can select two dates and switch back and forth from them in a swiping motion, thus seeing change simultaneously, rather than selecting back and forth. However, unlike Google’s program, it compiles various dates into certain broad time categories, sometimes adding sections of imagery beyond a certain scope.

- Maxar: The team utilized Maxar as a tertiary imagery source. While high-quality, certain locations are only partially photographed, while others have no historical imagery beyond a certain time period, thus not fully extended backwards into the project’s scope. Also, some imagery does overlap with the previous two sources, as both Google and ESRI utilize Maxar imagery within their respective programs.

Supplemental open-source information was collected with a managed attribution platform (Authentic8 Silo) for sites/search engines that present topical/technical risks to systems. Some sources include:

- Baidu: Baidu is China’s foremost search engine, equivalent to Google in the US. Using it as intended (as a search engine) provides access to Chinese government sites, as well as Chinese-language media, in their original published format. However, as content is largely censored or otherwise controlled by the Chinese government, the trustworthiness of search engine results is low.

- Yandex: As with Baidu, Yandex is Russia’s foremost search engine. It provides access to original-language Russian government publications and media sources. Though less censored than Baidu, Yandex’s search results are tailored towards government-positive articles and media, thus making its trustworthiness low.

- OpenRailwayMap: OpenRailwayMap is based on the OpenStreetMap geospatial platform. Though comprehensive in seemingly including every rail line around the world, its open-source nature makes its credibility moderate, as it is likely inaccurate at some portions (simply due to a lack of information on certain rail lines).

Data Processing and Preparation

An Excel sheet was created to catalog data for each border crossing. The Excel sheet included:

Data Processing Fields

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Location Names | Names of the individual border crossings |

| Coordinates | X and Y, in decimal form |

| Crossing Type | Road or Road & Rail |

| Quarterly chage columns | Range from Q1 2020 to Q4 2024 |

| Indicator Codes | Incorporate category (road/rail- letter codes), type (status of construction progress- numbers), country (C/R for China/Russia) |

Afterwards, the data was cleaned for simplicity, converted into a comma-separated value (CSV) file, and then imported into ArcGIS to visualize with a time slider.

Discussion

From 2020 to 2024, infrastructure development at China-Russia border crossings likely followed economic and political drivers within each country more than weather conditions, with China maintaining year-round construction and Russia concentrating work in Q2–Q3. Road infrastructure saw more activity than rail, likely due to higher maintenance needs and strategic priorities with road-based travel. On the Chinese side, reduced traffic during COVID likely enabled steady progress, while seasonal traffic peaks possibly explain recurring infrastructure degradation. In contrast, Russian activity was more limited, likely due to economic constraints and seasonally-based construction cycles, where although there was construction in Q4 and Q1, work increased during the warmer months of Q2 and Q3.

Joint Trends

Despite harsh winters, infrastructure projects, especially roads, likely continued to progress due to economic and political drivers, while rail upgrades remain limited, possibly due to lower maintenance and cost needs.

First, the authors determined it is likely that weather conditions do not impede progress on infrastructure projects, with construction noted (either in progress or completed) in Q4 and Q1 of most years, despite the cold and sometimes snowy climate of northern China and southeastern Russia. As stated in the previous section on Russian trends, other factors, such as economic and political drivers, likely play a role in construction progression.

Second, although railways pass through four of the nine China-Russia border crossings, there was little change in rail infrastructure, apart from Russia’s building of new tracks at Nizhneleninskoye. This could be due to railroads needing less upkeep as opposed to roadways, both in regard to physical maintenance and the financial expenditures behind such.

Chinese Side Trends

China’s reduced traffic during COVID likely enabled steady infrastructure progress as projects could continue unhindered by vehicle transits through construction areas, while seasonal wear and increased traffic potentially explain higher rates of infrastructure degradation in Q2 and Q3 across all years.

First, most construction projects observed were completed between Q2 2020 and Q4 2021. This likely coincides with the lack of international travel during the COVID pandemic, allowing Chinese construction firms to continue progress unabated by passenger travel. Second, also likely coinciding with the pandemic, there was a decrease in commercial traffic between Q2 2020 and Q3 2023. Third, most infrastructure deconstruction or degradation occurred in Q2 and Q3 across all years, which could be due to increased passenger or commercial traffic. This can impede efforts to repair or improve infrastructure and can also warrant the removal of temporary structures for logistical or aesthetic purposes.

Russian Side Trends

Across 2020 to 2024, Russian locations showed less indicators of both construction and deconstruction, likely due to economic factors, as well as construction cycles culminating in the second and third quarters of each year, despite Chinese cycles continuing year-round.

First, there were comparatively fewer indicators of construction, as well as deconstruction, than on the Chinese side, especially during the COVID pandemic from Q1 onward, into Q2 and Q3 2021. Second, most construction projects were completed in Q2 and Q3 across all years (primarily from 2022 to 2024), likely indicating that these were the busiest construction seasons. Since China appeared to continue construction in the winter months, this further indicates that other conditions beyond weather play a factor in project cycles.

By Location

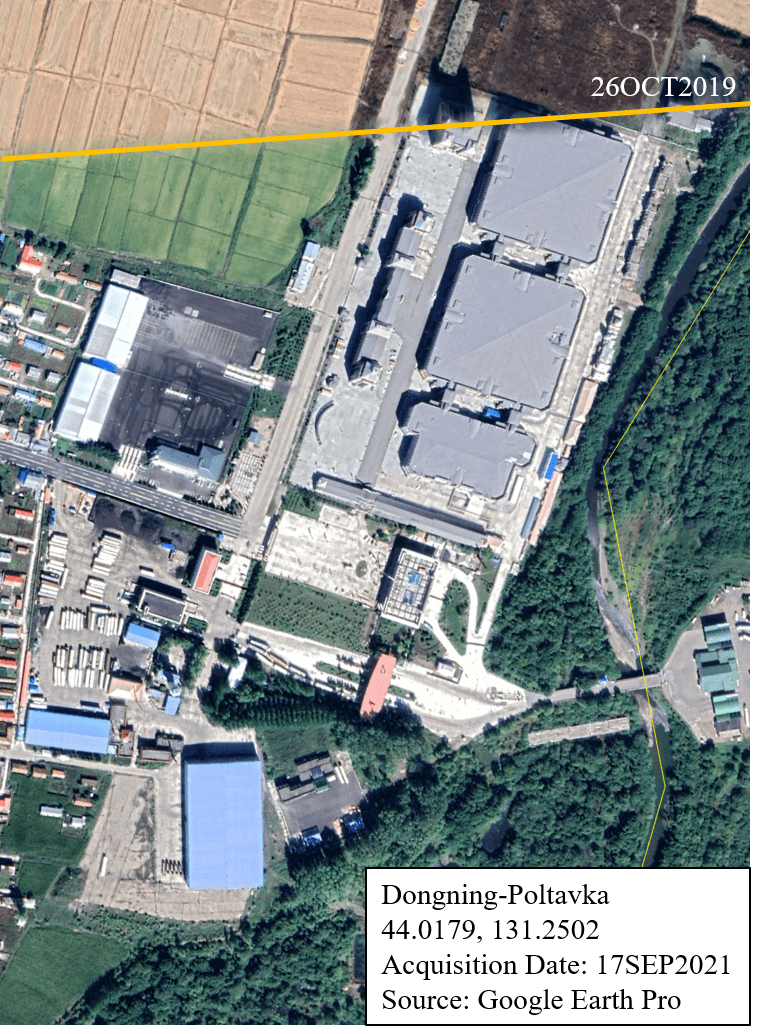

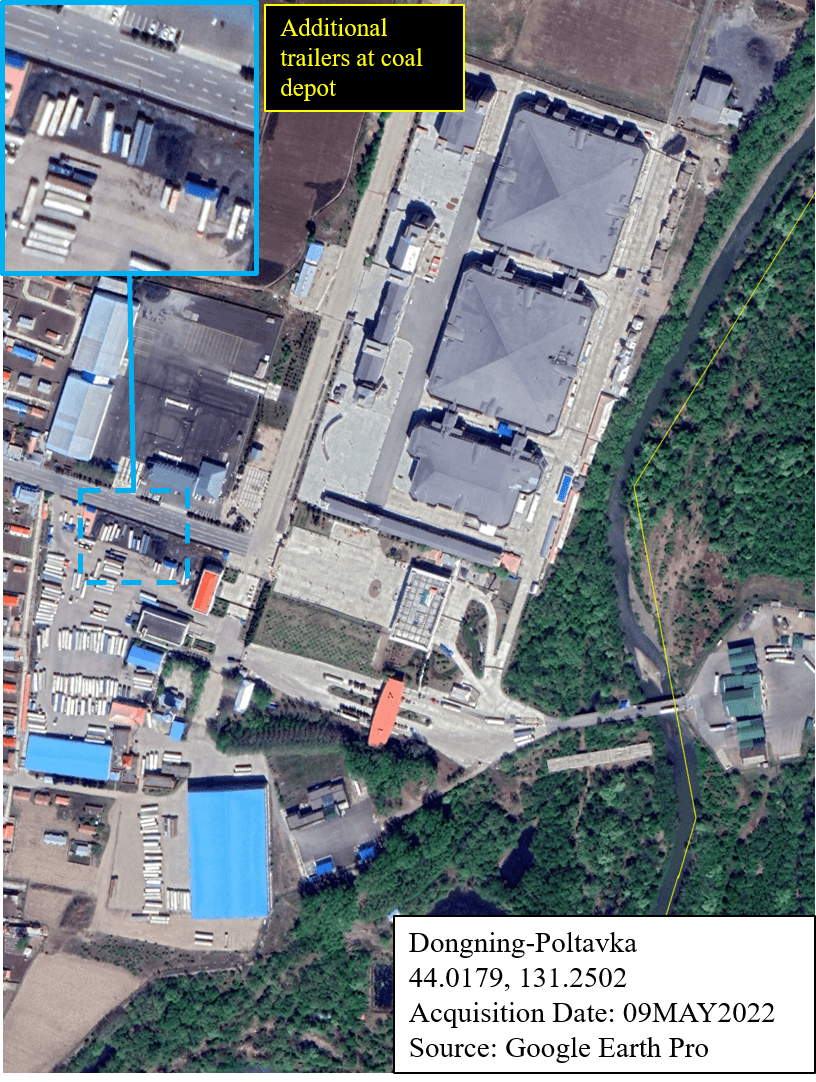

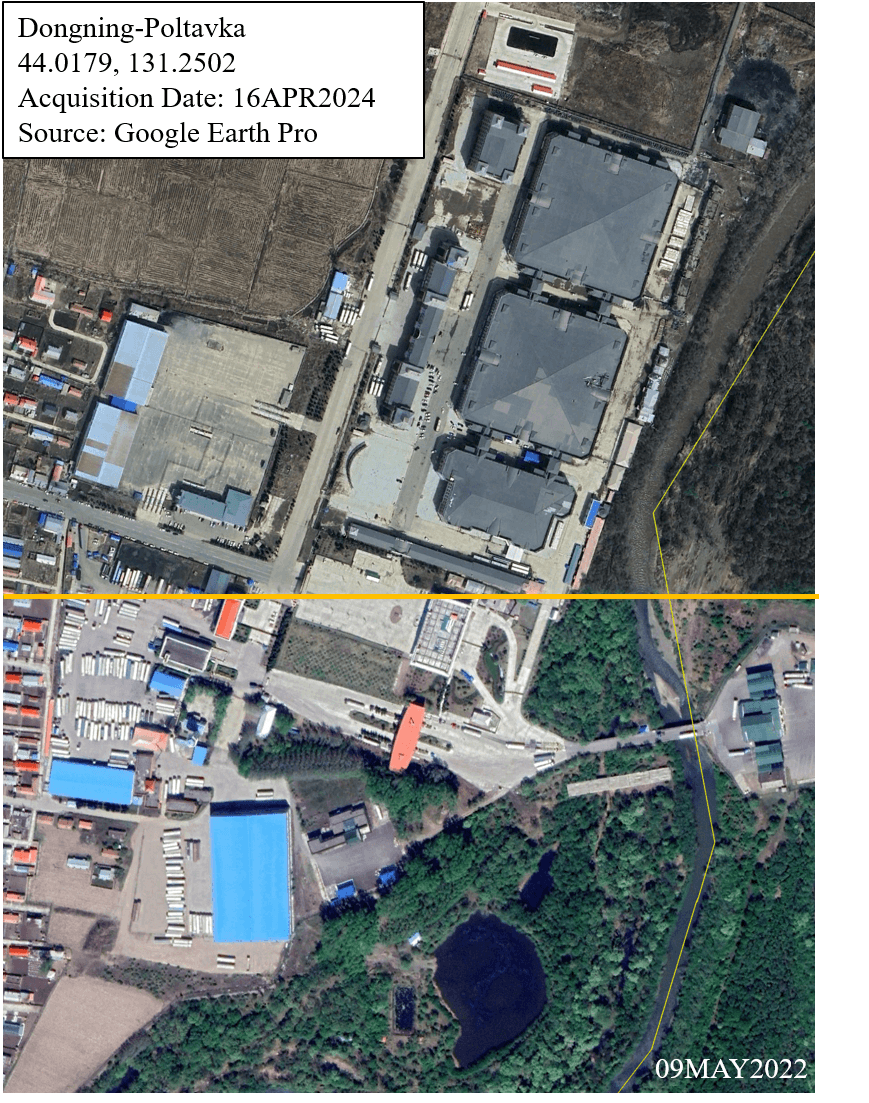

Dongning, China – Poltavka, Russia (Road crossing only)

There have been few changes on the border crossing between Dongning, China and Poltavka, Russia from 2020 to 2024, likely contributing to increased economic trade between the two municipalities, through changes in traffic in China and parking infrastructure expansion in Russia.

Dongning

On the Chinese side of the border, the only development has been an increase in semi-truck traffic around a likely small coal depot, from 75 trucks in Q3 2021 to over 160 trucks in Q2 2022. This coincides with overall traffic remaining a constant across China's section of the border over the past five years. This demonstrates a continuation of road-based economic activity along the China-Russia border and indicates that it likely increasing.

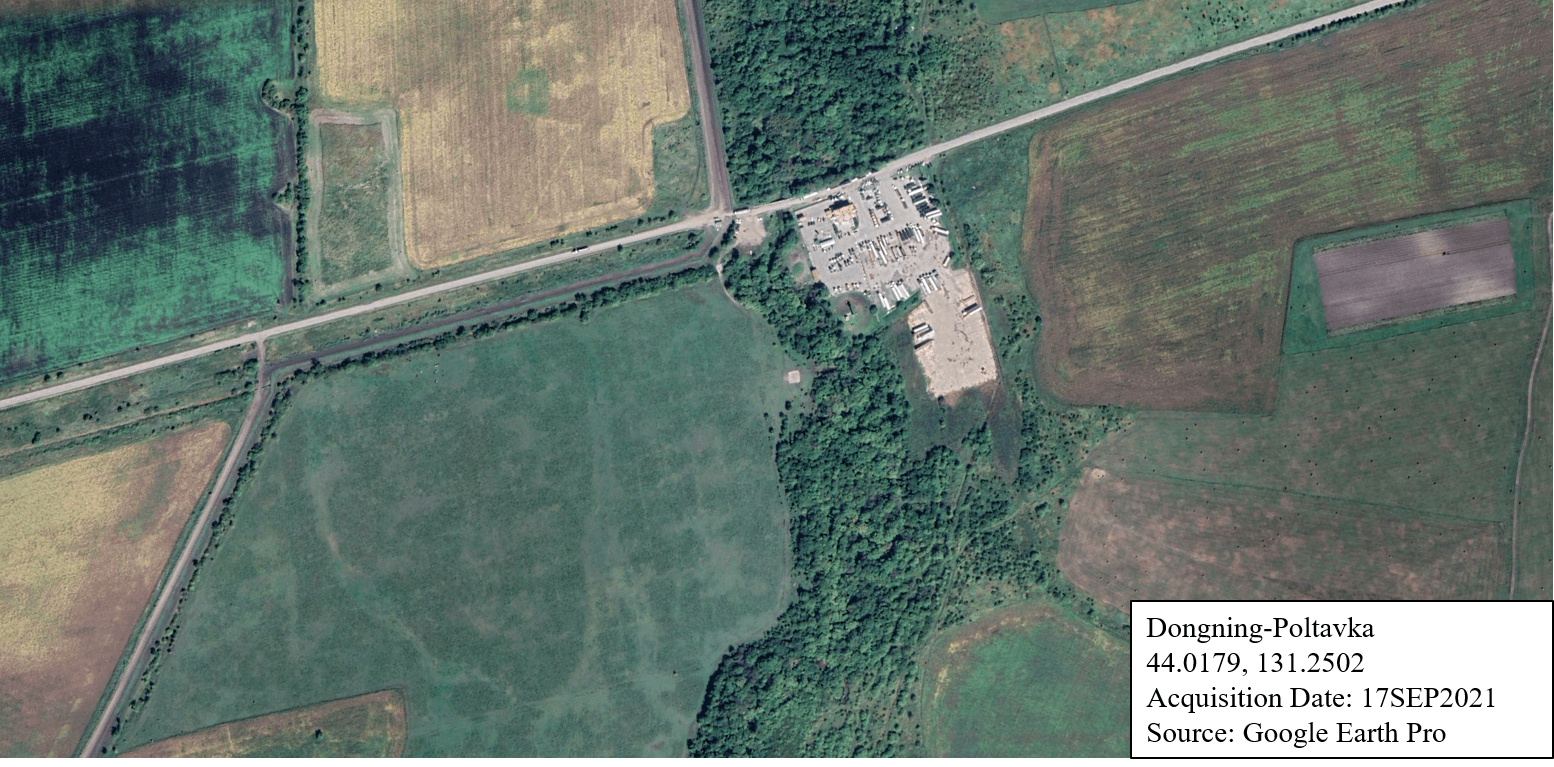

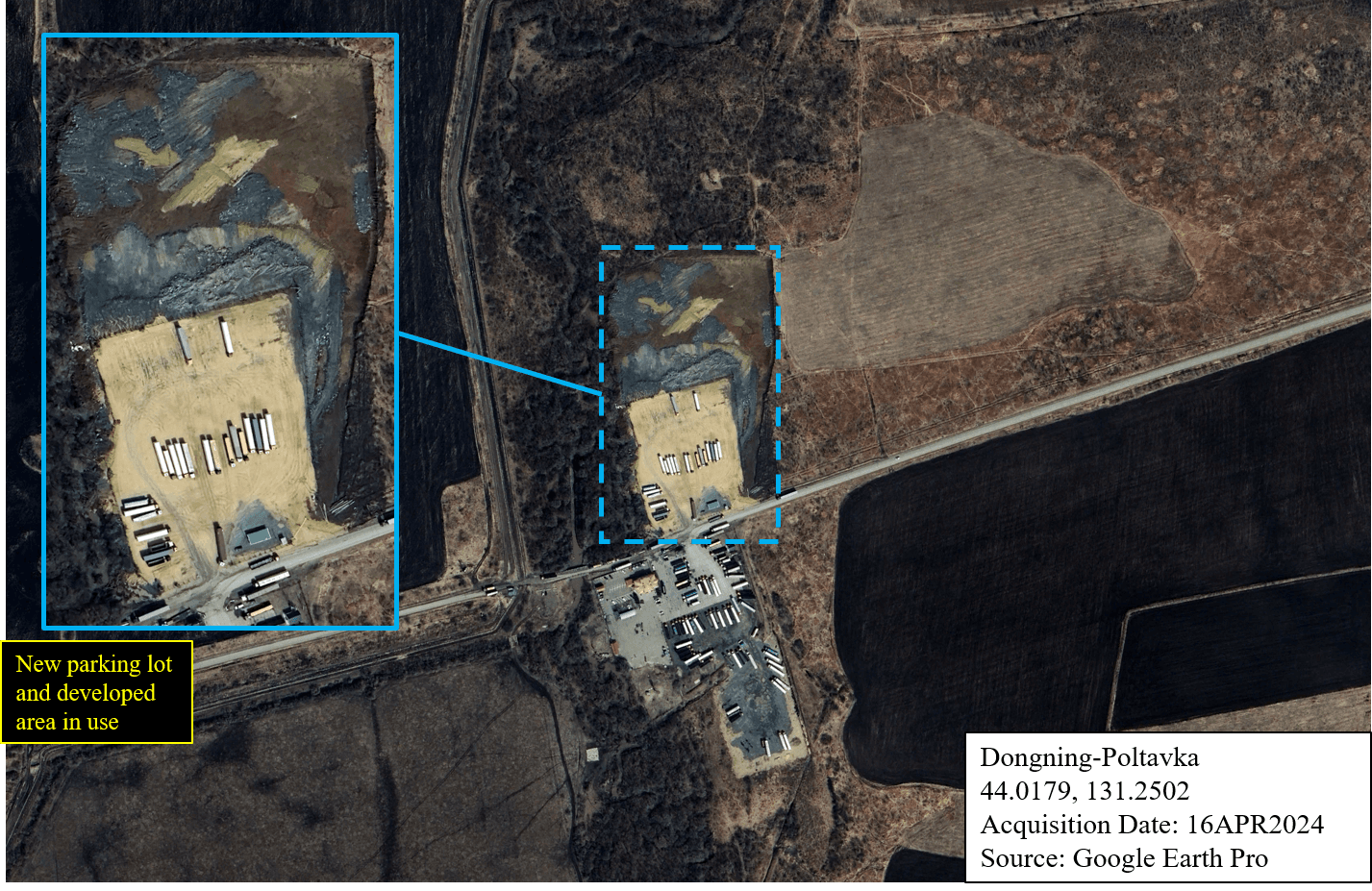

Poltavka

The one notable change in the Russian side of the border is the relatively recent development of an isolated parking lot 2.5 miles from the border. Before the parking lot’s completion in Q2 2024, the dirt plot preceding it was primarily populated with semi-trucks and some automobiles. The new parking lot remedies this issue despite an increase in overall traffic at the facility, as there were 81 trucks in Q3 2021 compared to 112 in Q2 of 2022. This indicates a development in road-based infrastructure to support growing economic activity in this section of the border. Given the fact that both the Chinese and Russian sides of the border are experiencing growing truck traffic, it is highly likely that economic activity between China and Russia is increasing along the Dongning-Poltavka border, potentially becoming an economic hub for the two countries in the near future.

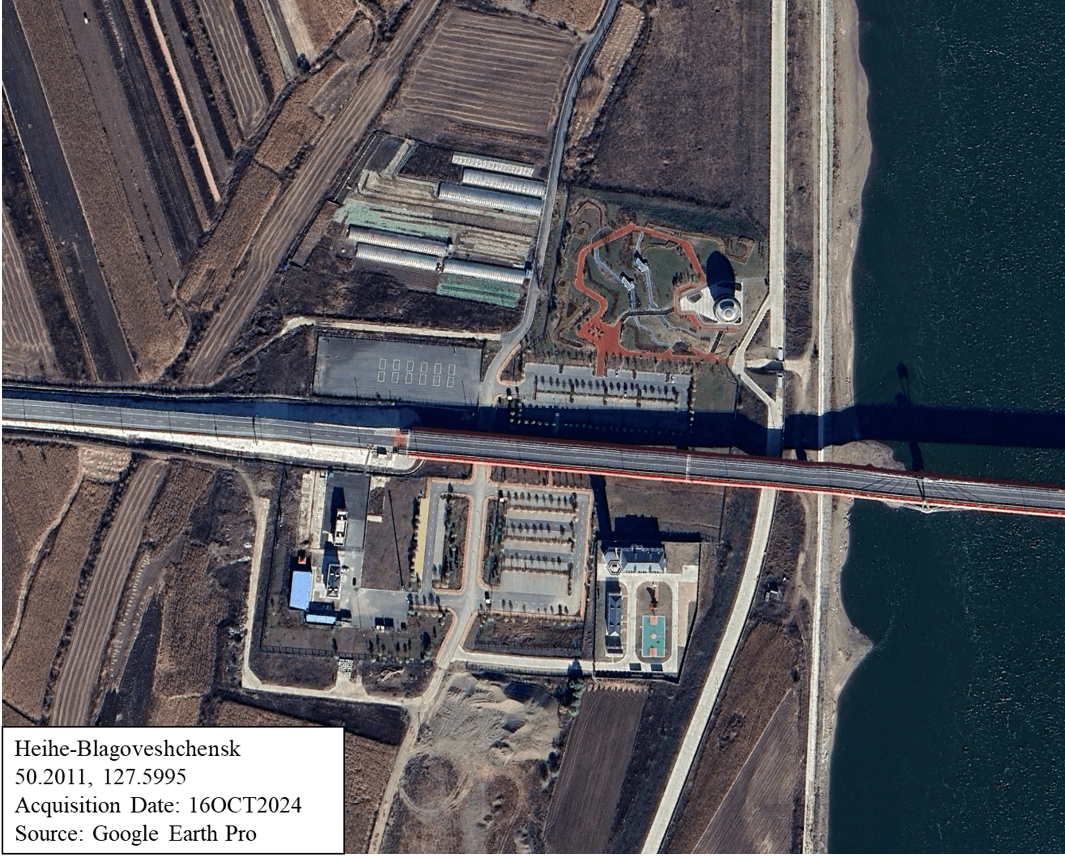

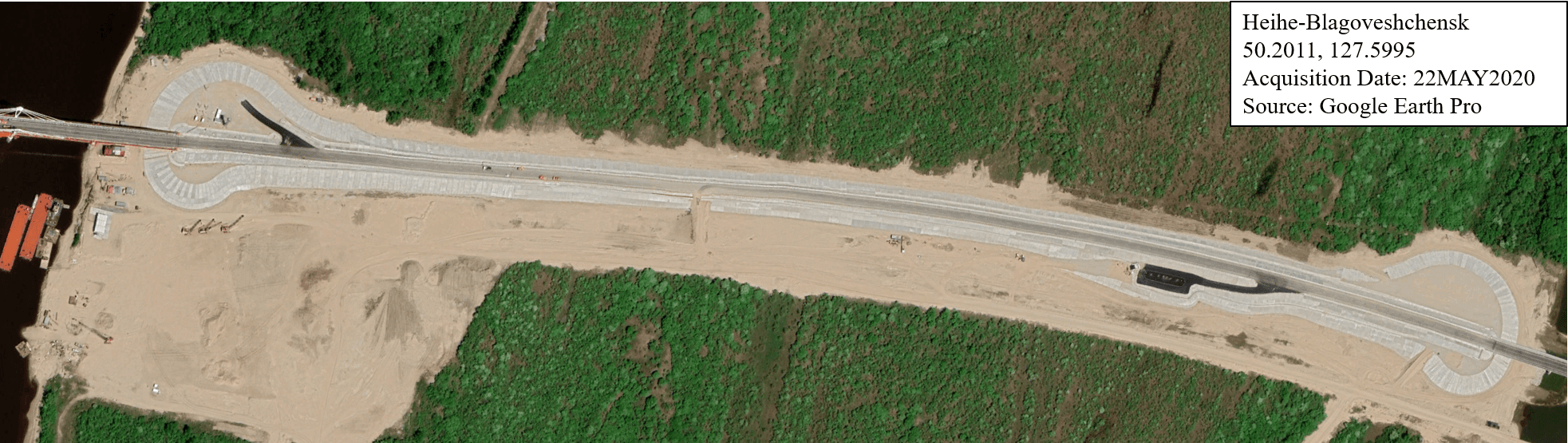

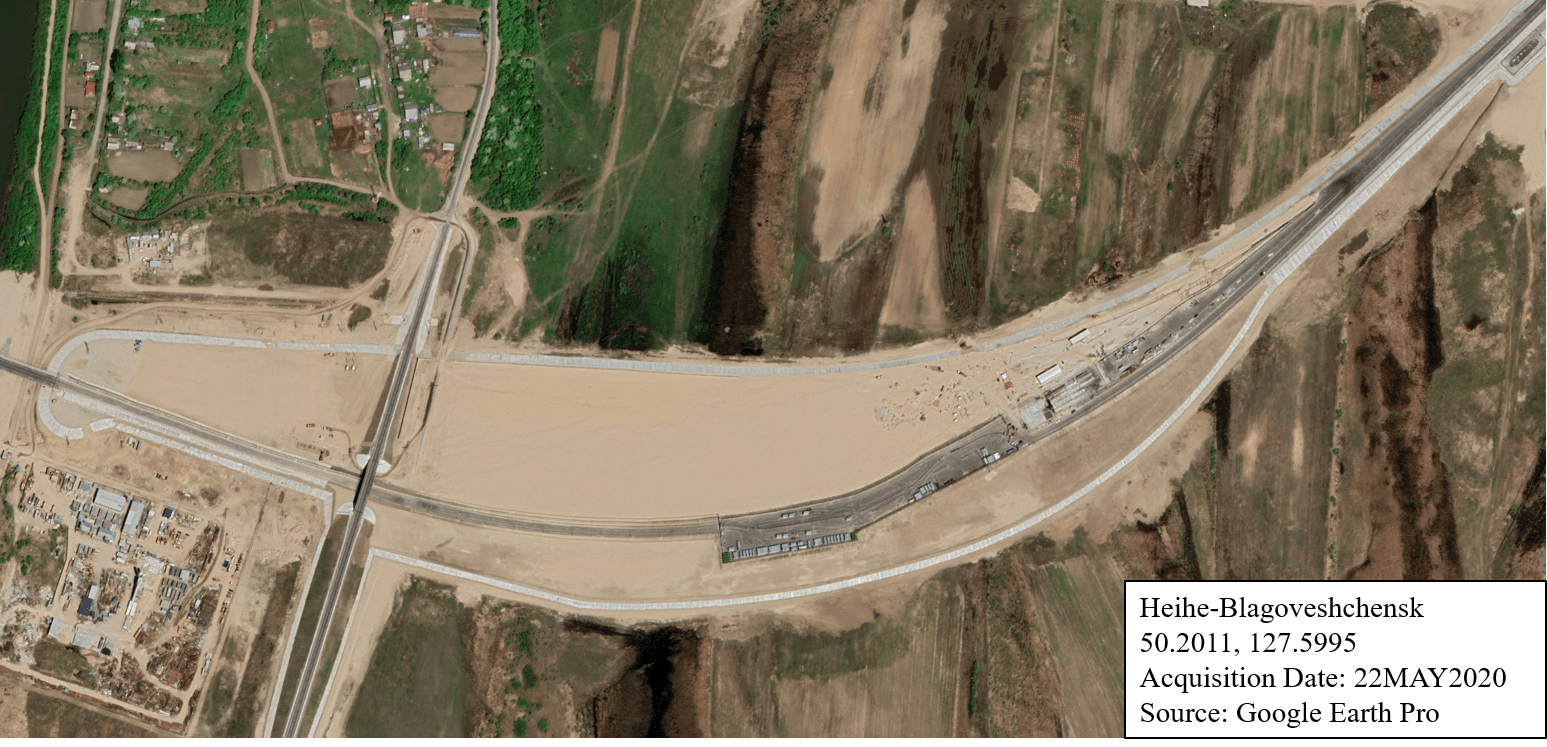

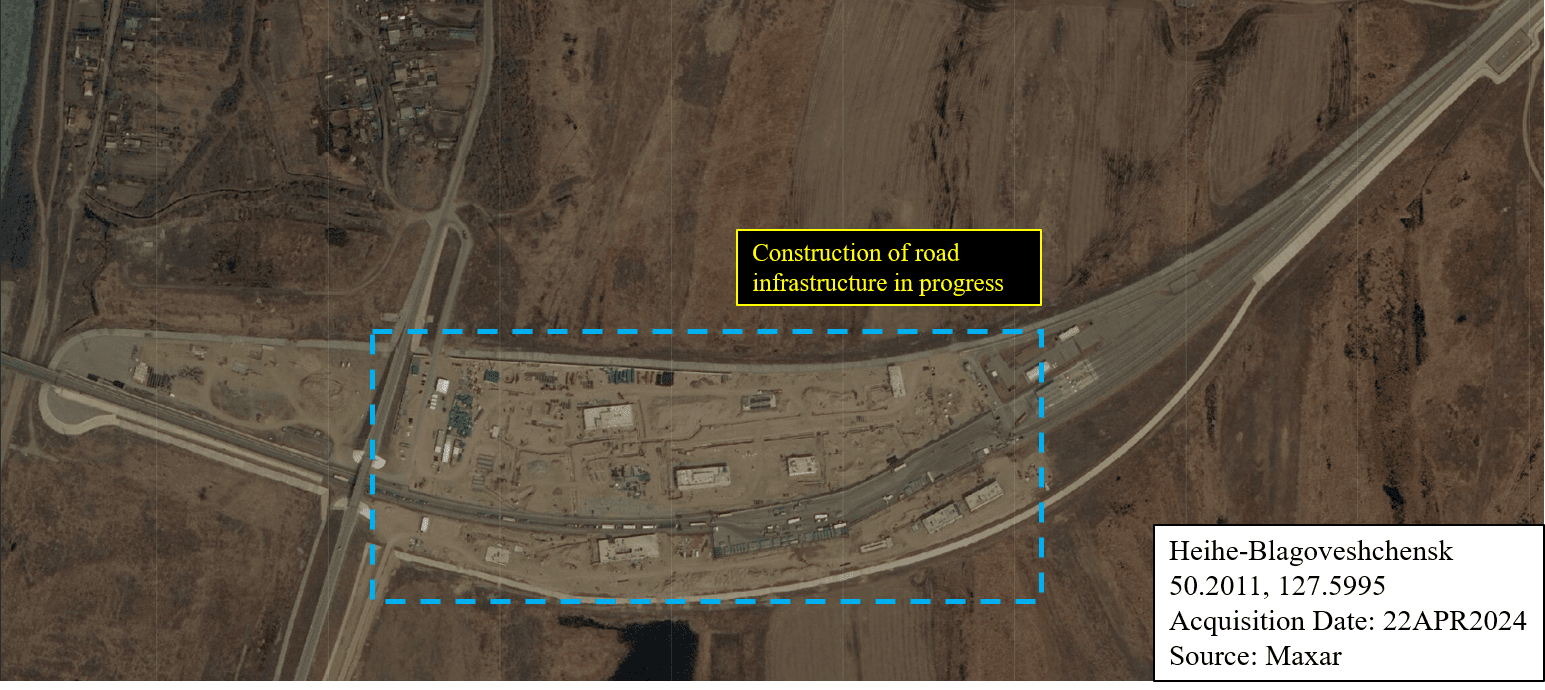

Heihe, China – Blagoveshchensk, Russia (Road crossing only)

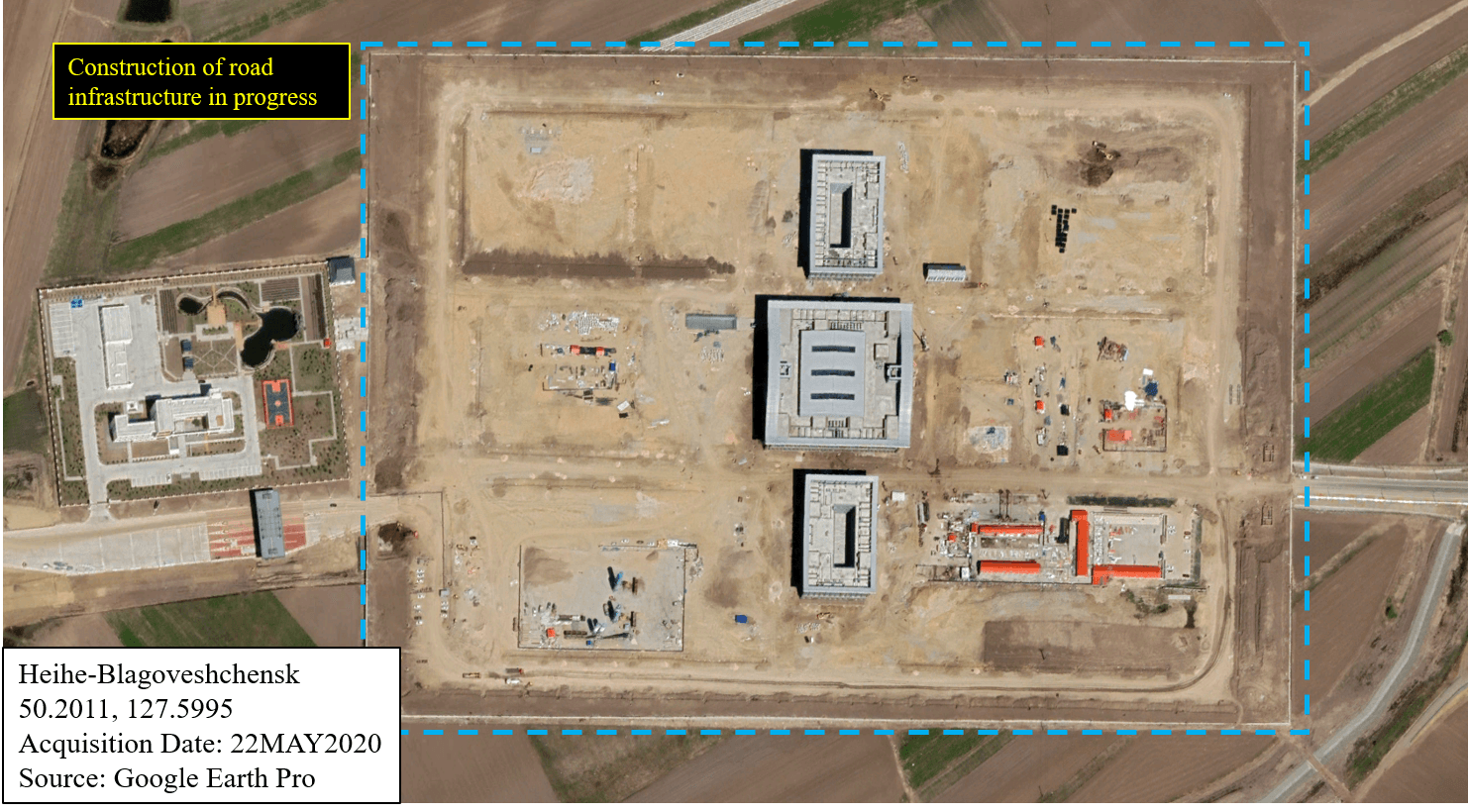

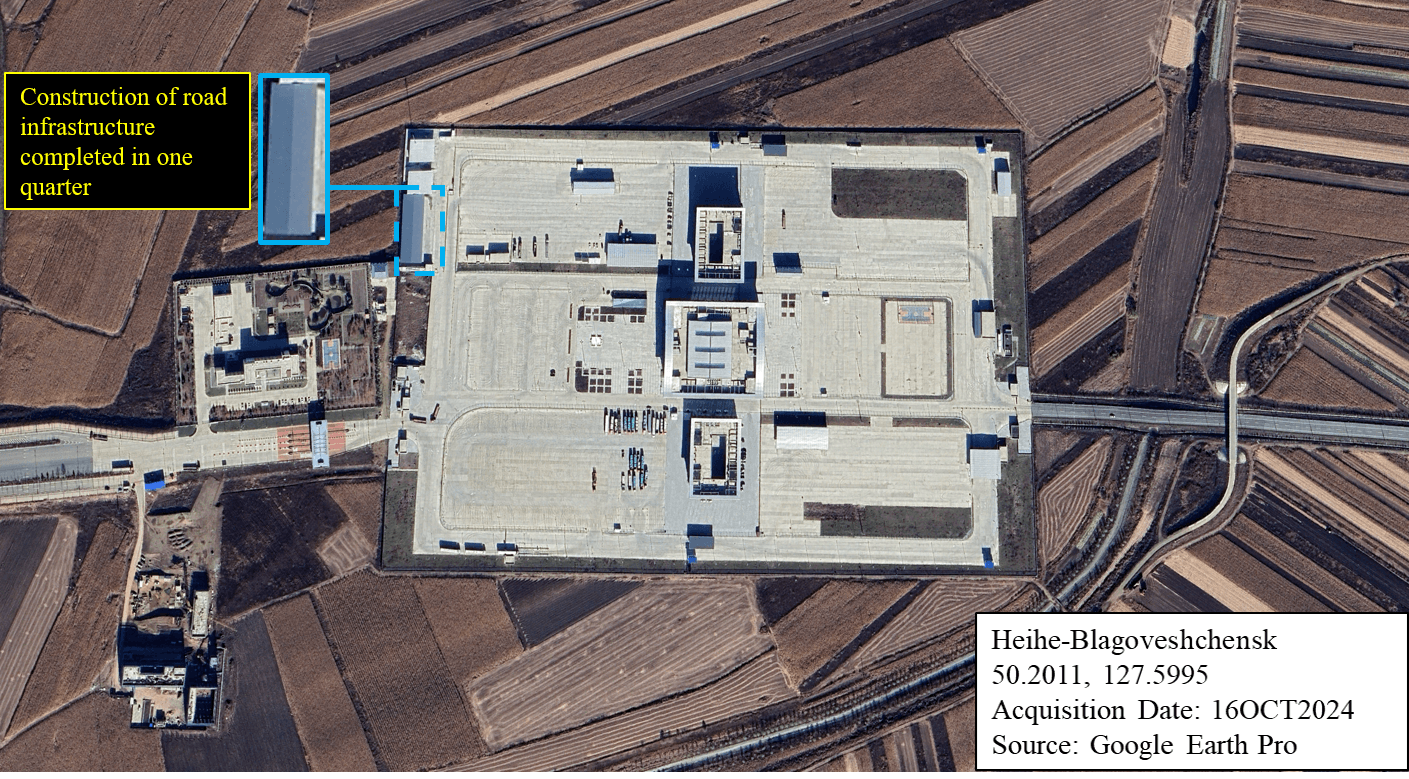

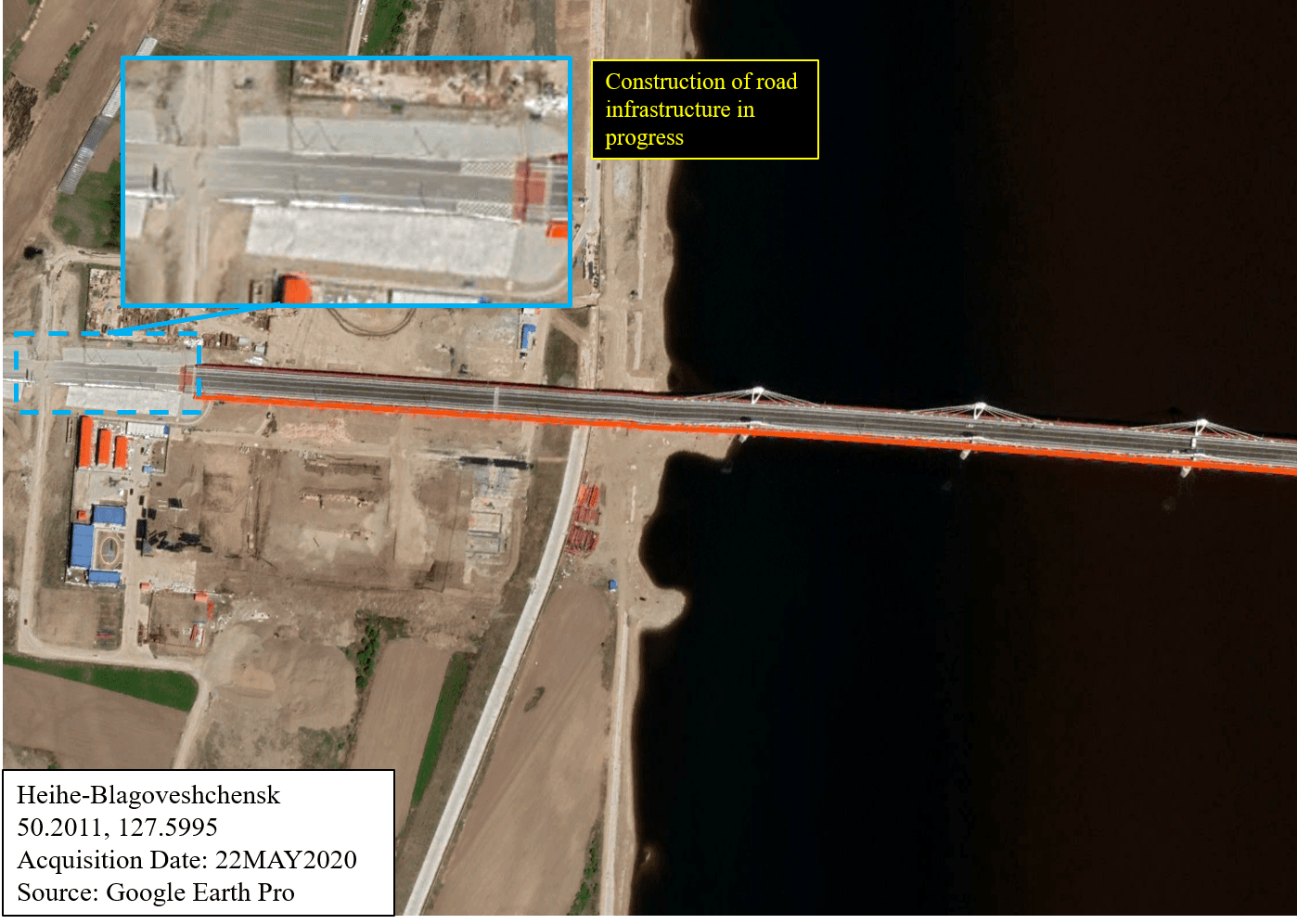

The border crossing between Heihe, China, and Blagoveshchensk, Russia has shown a significant increase in road infrastructure from 2020 to 2024, primarily centered around the new highway bridge constructed in late 2019. These changes incorporated additional projects along the road on either side of the bridge, contributing to increased Chinese cargo inspection and storage capabilities; Russian construction projects in progress are of unknown purposes.

Heihe

On the Chinese side of the border, there has been a significant effort in developing road-based infrastructure near the highway bridge that connects Heihe and Blagoveshchensk; indicators of this type of development can be seen in both sections A and B. During Q2 2020, early stages of large-scale construction can be seen in section A, with the foundations set for multiple buildings. The completion of this construction was seen in Q1 2021; this site is very likely an inspection station, indicated by the presence of semi-trucks. The only development that occurred in section B during this period was the completed construction of the road that connects to the highway bridge. In Q2 2022, minor road-based infrastructure would be added near the entrance of the highway bridge.

Also on the Chinese side, over the course of 2022 and 2024, further construction of road-based infrastructure was seen in section A. In Q2 2022, minor developments can be seen near both entrances of this facility. In Q4 2024, the completed construction of a building that slightly resembles a warehouse can be seen near the northwestern corner of the facility. The same image also shows 26 semi-trucks parked side by side in the southwestern space of that area; this number is an increase from seven trucks in Q2 2024. It is likely that the facility is used to store and load cargo onto the freight trucks that are stationed there so that it can be transported directly to Russia.

Blagoveshchensk

On the Russian side of the border, there were rarely any indicators in section C alluding to the development of road-based infrastructure along that section of the road. In Q1 2021, a port that was in close proximity to the highway bridge was deconstructed. The port was likely removed due to its temporary nature of onloading and offloading construction material. In Q4 2022, there was evidence of construction taking place along the road, with four building foundations laid. As construction is still ongoing in that area as of Q3 2024, it is difficult to determine the type of infrastructure that is being built. Regarding road traffic, there were only three semi-trucks seen in line at the border in Q4 2022; by Q3 2024, this increased to 38 trucks seen.

A CNN article published in June 2022 describes the construction and opening of the Heihe-Blagoveshchensk highway bridge, which opened for use in that same month.https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/14/asia/china-russia-blagoveshchensk-heihe-highway-bridge-mic-intl-hnk/index.html[34] Despite imagery showing completion before our scope (late 2019), this delay is attributed to the COVID pandemic.Ibid[35] As of 2022, the bridge is known to only be used for cargo transport, but its proposed passenger capacity is around two million travelers per year; cargo is estimated for four million tons, totaling around USD 200 billion by 2024.Ibid[36] Both China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin expressed positivity about the bilateral political and economic effects of the bridge’s construction.Ibid[37]

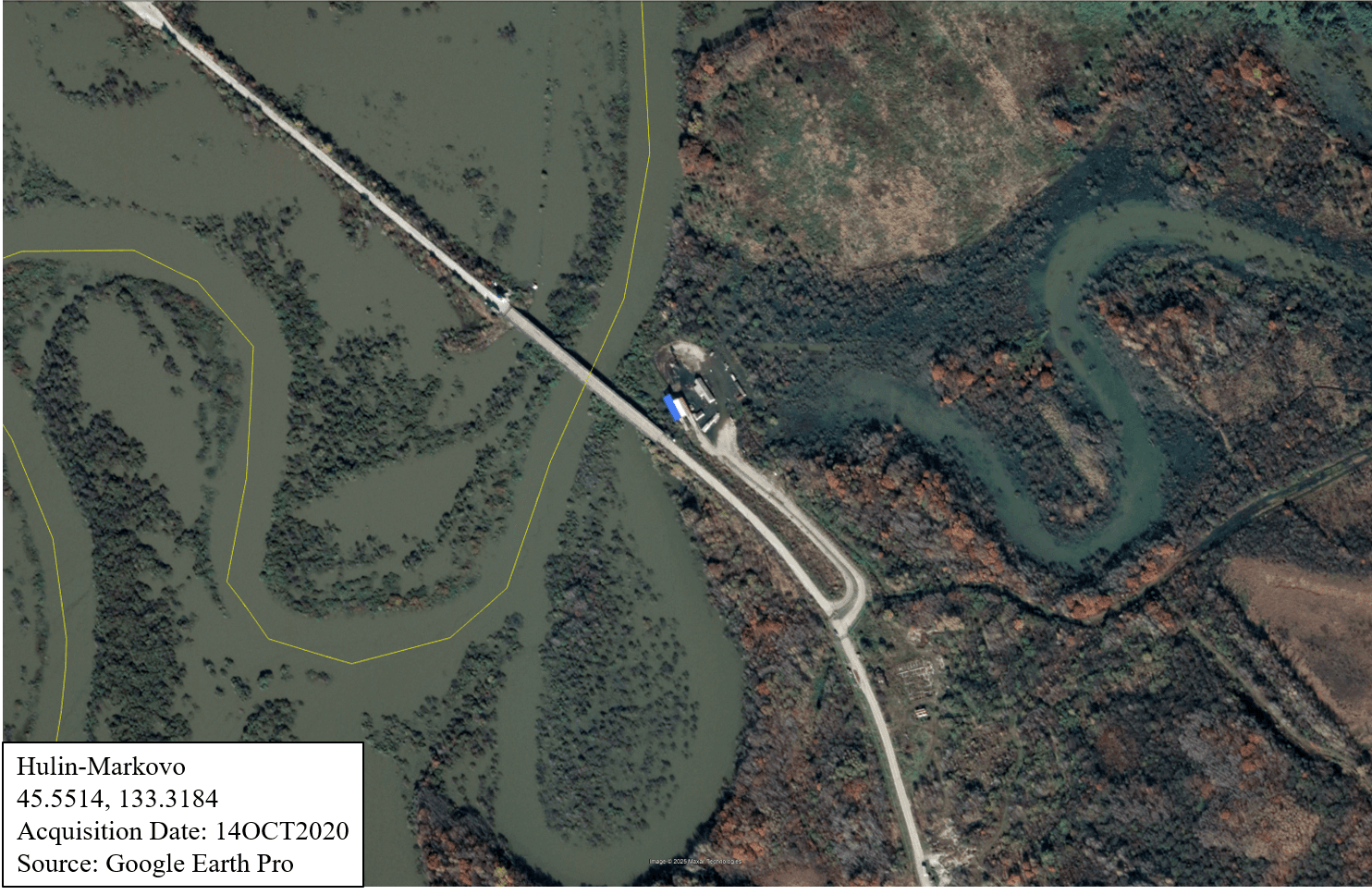

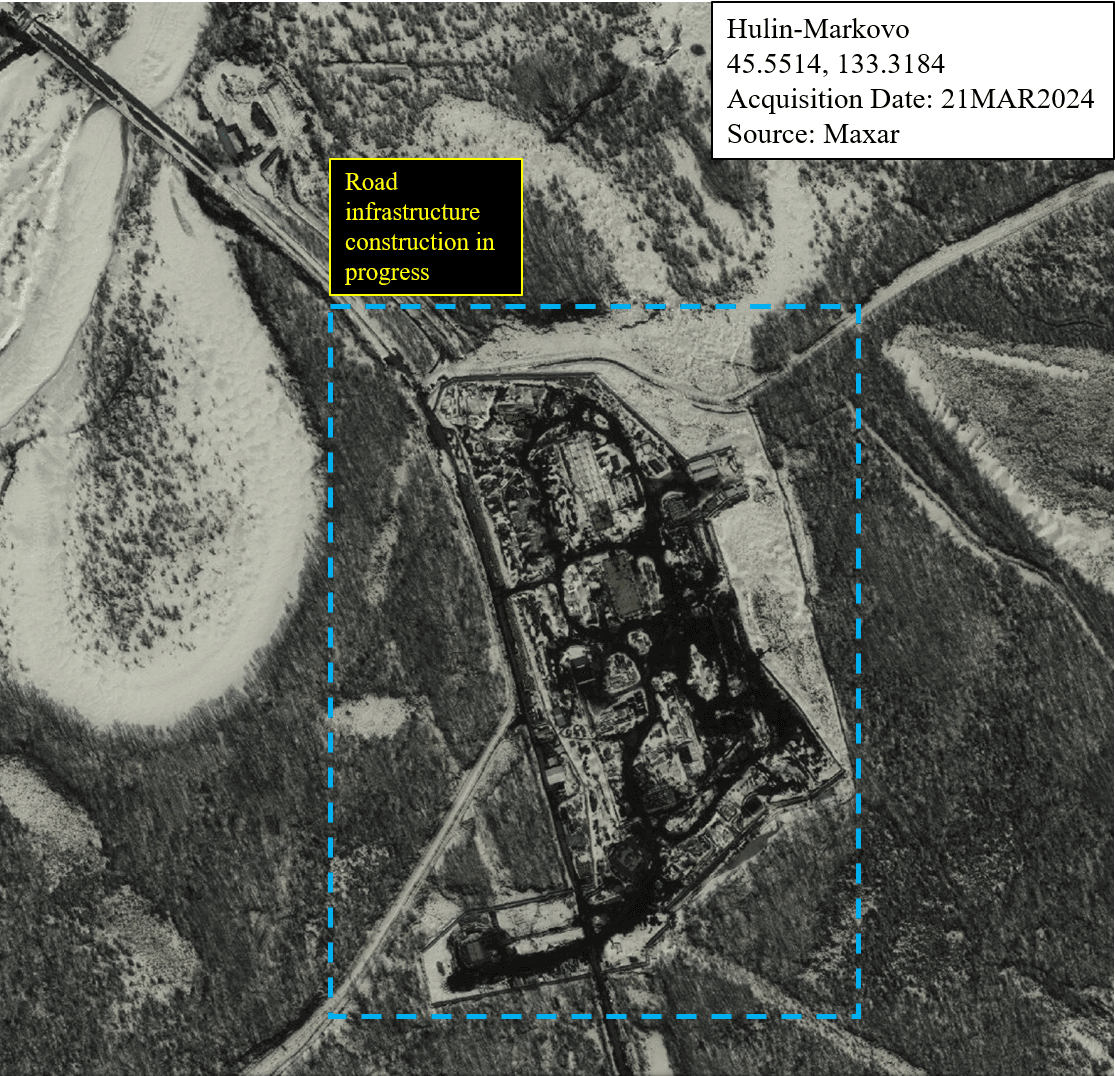

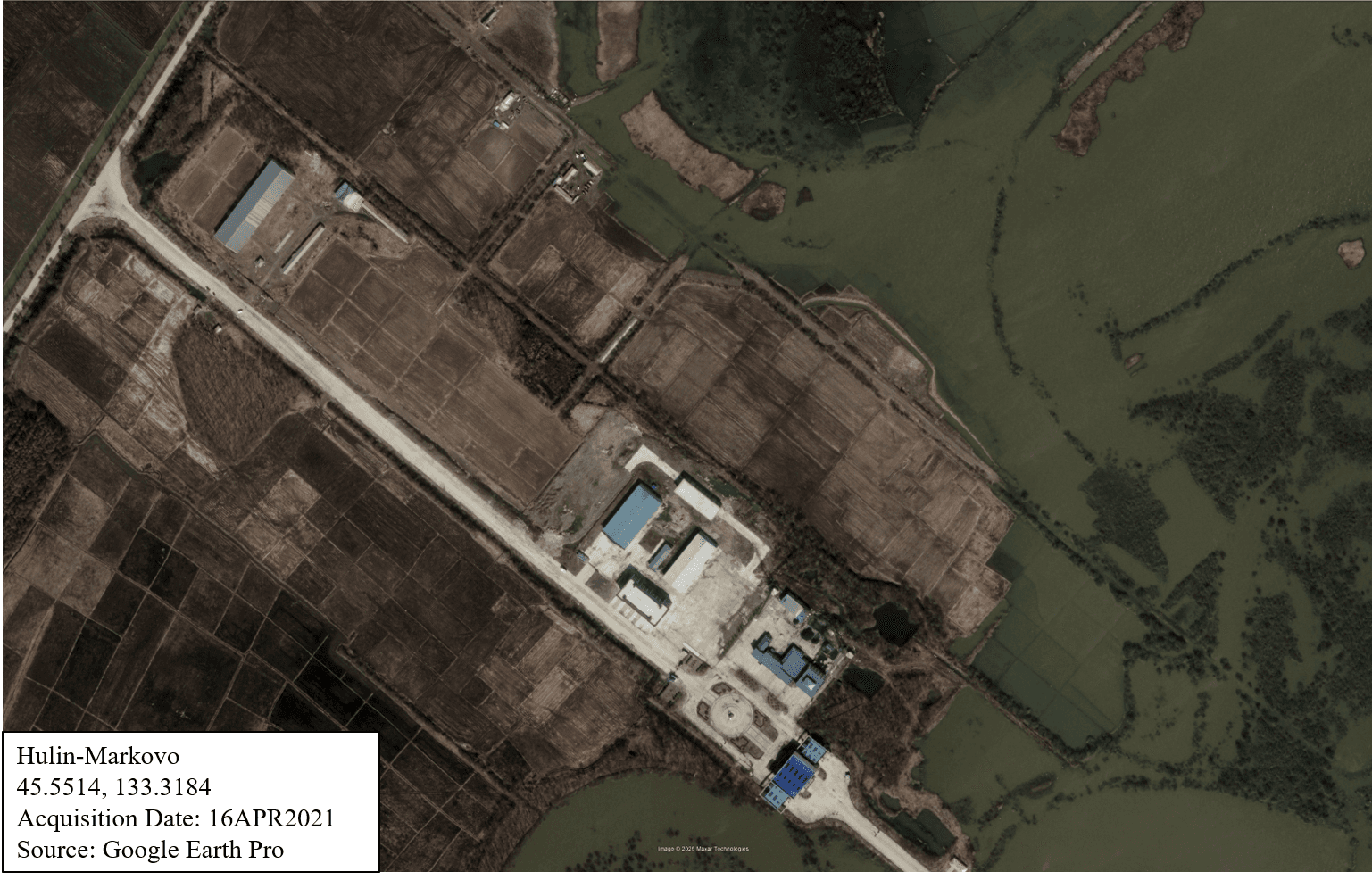

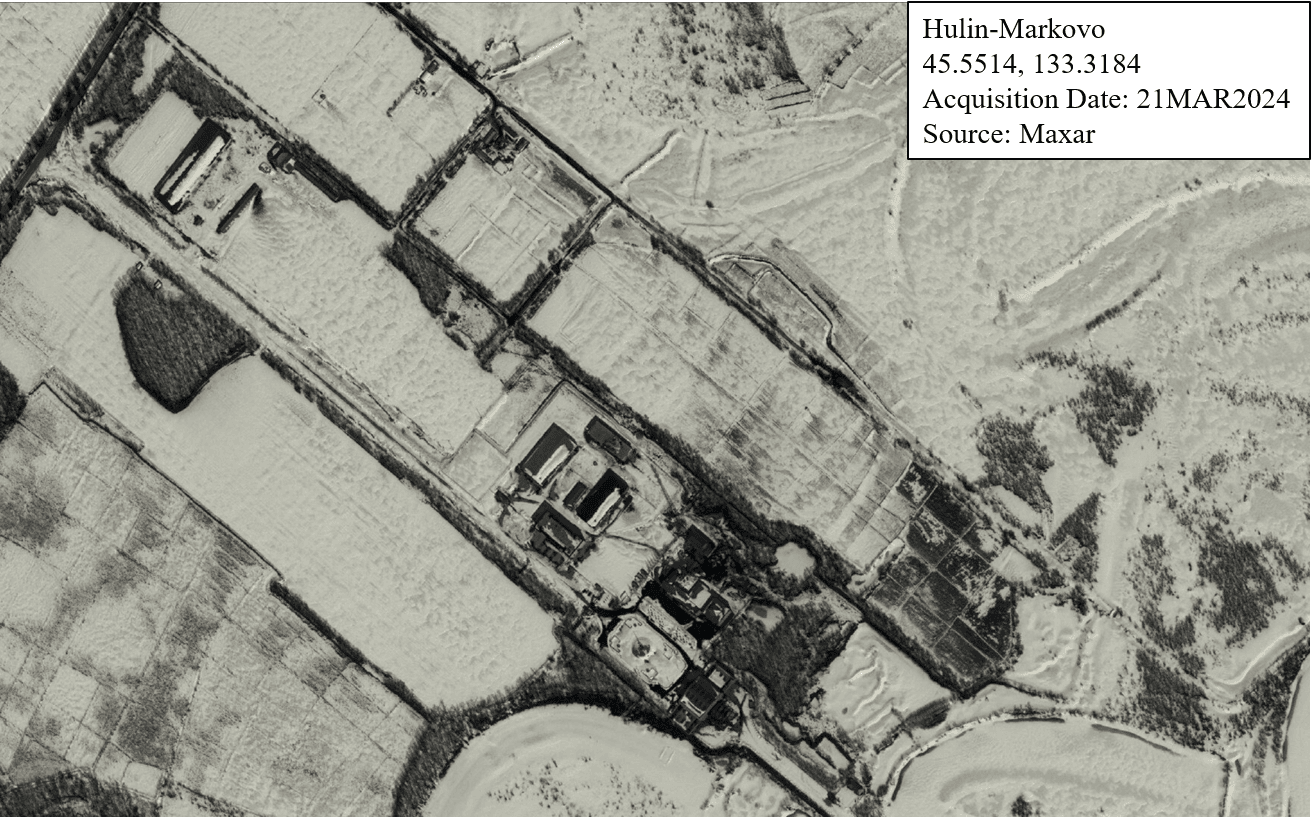

Hulin, China – Markovo, Russia (Road crossing only)

At the Hulin, China and Markovo, Russia border crossing, all infrastructure changes occurred on the Russian side, solely involving building construction along the cross-border road, likely indicating an increase in Russian interest of economic activity between Markovo and Hulin. The blue building just southeast of the bridge and river/border serves as a reference point.

Due to a lack of imagery between Q2 2021 and Q4 2023, it is unknown when the following construction began. Regardless, on the Russian side, road-based infrastructure construction was first seen in Q4 2023, where at least two confirmed buildings were under construction; this is possibly four separate buildings, but this is still unknown. The purpose is also unknown, but as the construction site incorporates both sides of the road and is about 0.5 miles from the border, it is likely related to border security or economic activity. This construction continued into Q1 2024.

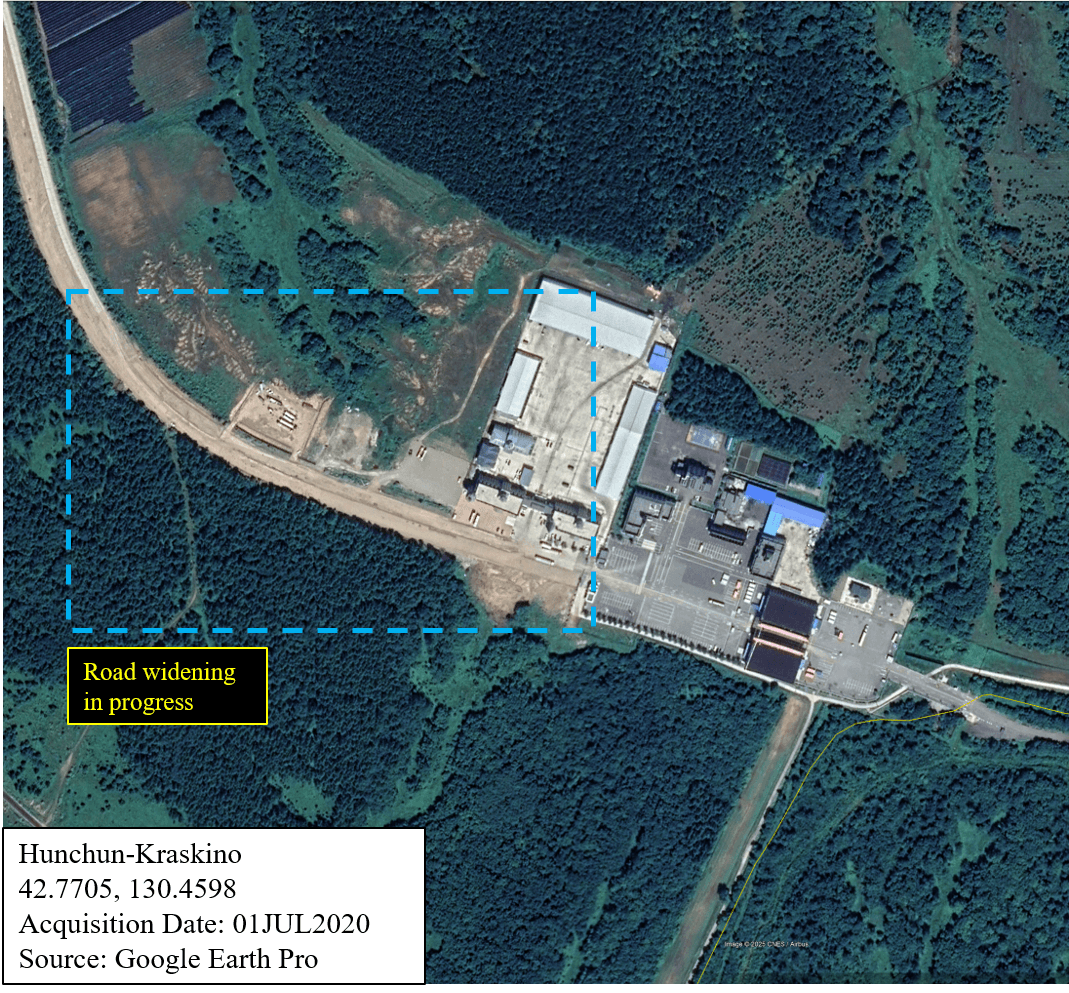

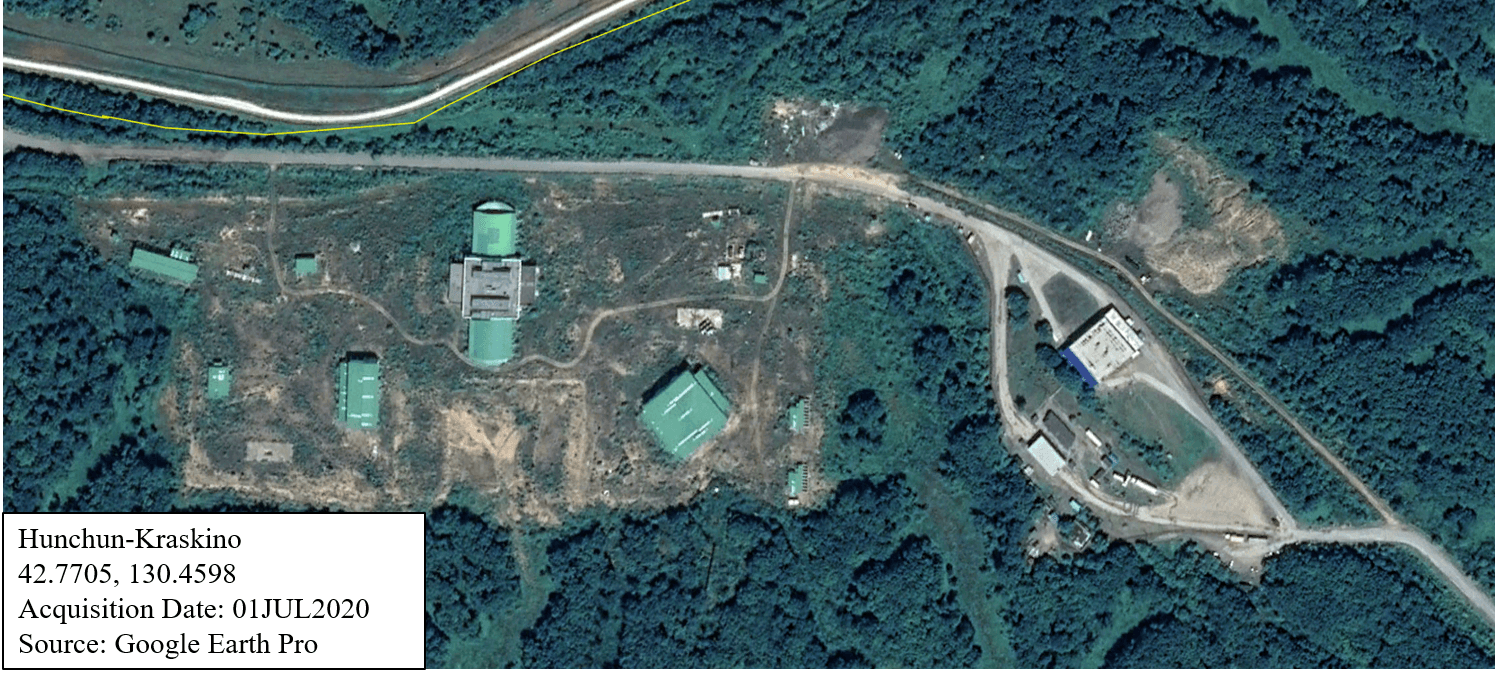

Hunchun, China – Kraskino, Russia (Both road and rail crossing)

The border crossing between Hunchun, China and Kraskino, Russia saw a gradual increase in road-based transport infrastructure between 2020 and 2024, aiming to better facilitate cargo transportation via lane additions, as well as new storage facility construction. Despite the presence of rail lines, all changes solely related to road-based infrastructure.

Hunchun

On the Chinese side of the border, there was expansion and widening of the road to allow larger vehicles to transport cargo. During Q3 2020, there were indicators of ongoing construction on the road towards the border crossing. There was also construction taking place near the west side of a warehouse facility residing near the border. Images collected during Q4 2023 and in Q1 and Q2 2024 further corroborate continuing construction, which showed the completion of nine large warehouse facilities in Q4 2023, along with the installation of a fueling station near the border crossing. The presence of these facilities indicates a greater focus on commercial truck-based logistics and transitory storage. This could prove beneficial for Hunchun, as it is a significant hub for e-commerce and other commercial activities in that region.

Kraskino

The Russian side of the border also showed indicators of road infrastructure development. Imagery collected from Q2 2024 shows large-scale construction activity occurring on a large plot of land, comprising several small and large buildings. The roads that lead into the site were widened, most likely to allow larger freight and other types of cargo trucks to enter the area. Like the activity occurring on the Chinese side of the border, it is possible that the site is being used to develop a large-scale warehouse facility. The establishment of road infrastructure to the east of the site, along with two ongoing construction projects taking place near the road towards the border, further indicates this likelihood.

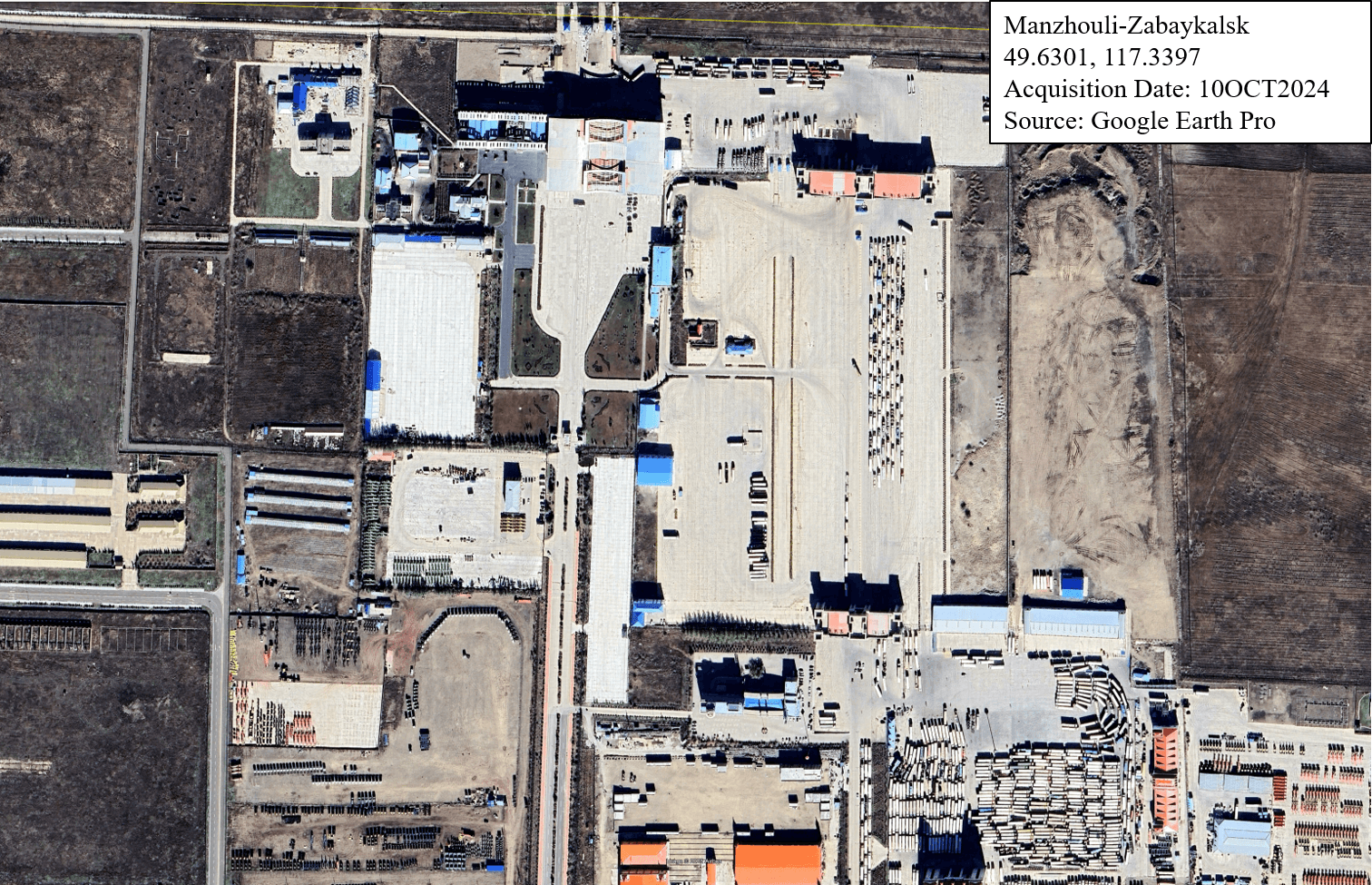

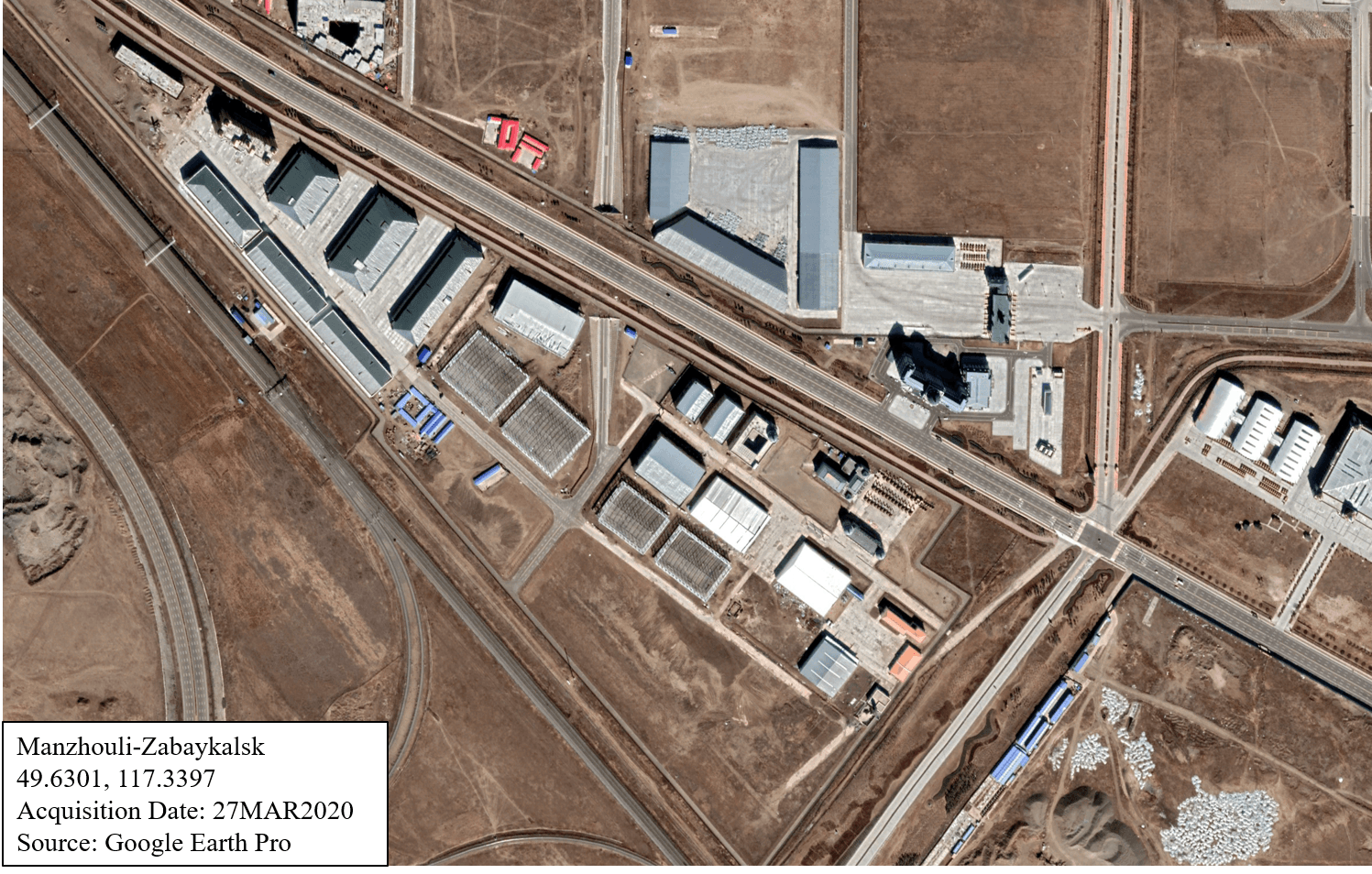

Manzhouli, China – Zabaykalsk, Russia (Both road and rail crossing)

All changes observed occurred on the Chinese side of the Manzhouli, China and Zabaykalsk, Russia border crossing, and were entirely road-based, primarily regarding changes in commercial traffic patterns, as well as tourist area construction. This indicates an increase in economic activity across the border at this location related to the importing of goods into China.

Beyond Q3 2021, imagery showed no apparent changes to infrastructure, but throughout the time scope, commercial traffic fluctuated. Coinciding with the COVID pandemic, the number of semi-trucks around the border significantly decreased within Q2 2020, and remained low (at 21 trucks present) until Q3 2021, where traffic increased to over 80 trucks present. However, between Q4 2021 and Q3 2023, traffic appeared to decrease from around 30 trucks to around 20 trucks present. From Q3 2023 to Q4 2024, the number of trucks significantly increased from 20 to over 80 trucks again, showing longer lines across the border and within holding areas.

In Q2 2020, two buildings were under construction near the main cross-border road within the designated tourist/visitor area. Construction continued through Q3 2020, where a small building (separate from the two under construction) had its roof painted. By Q3 2021, both buildings were completed; one appears to be an observation tower for tourism, while the other’s purpose is unknown.

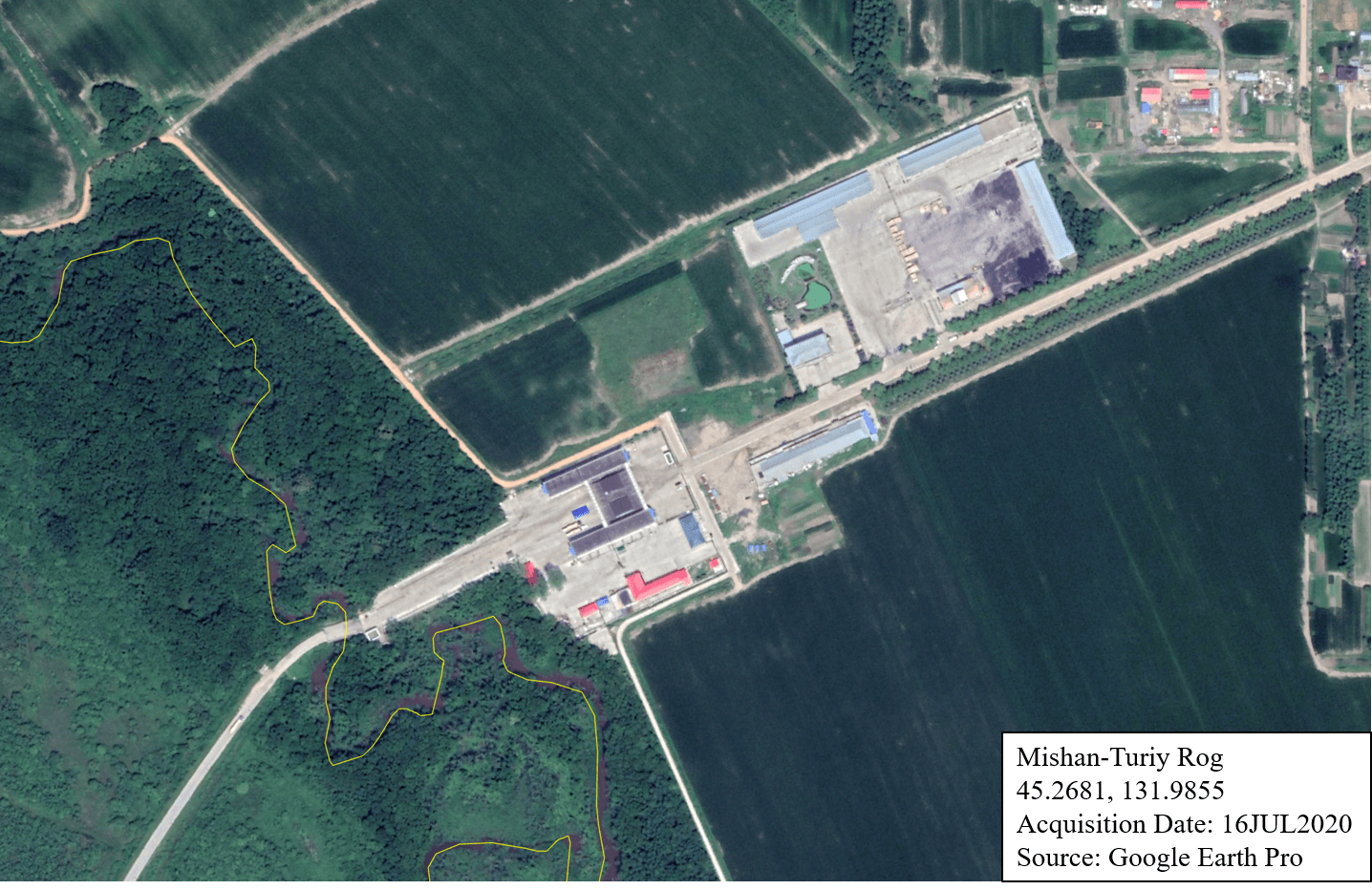

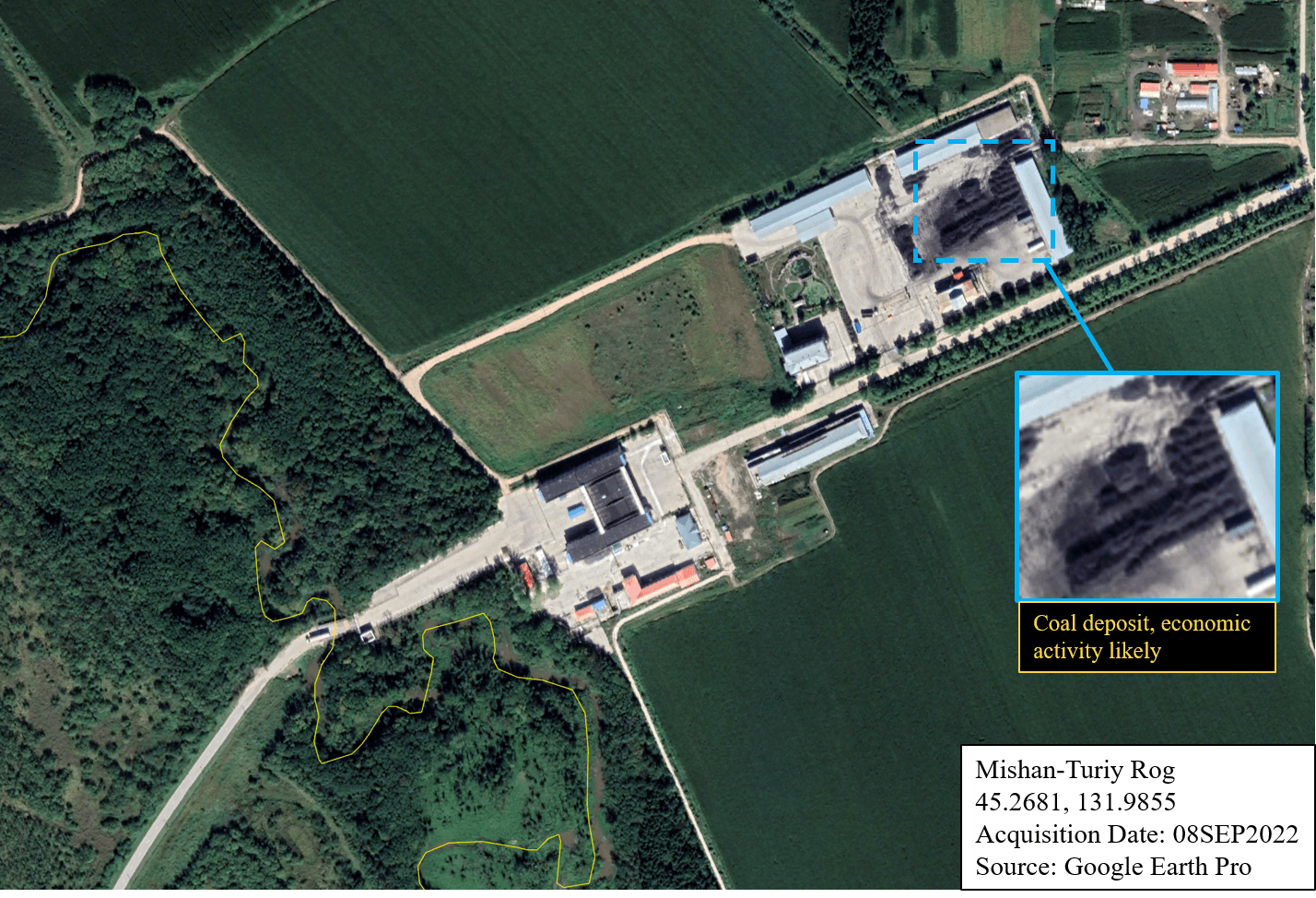

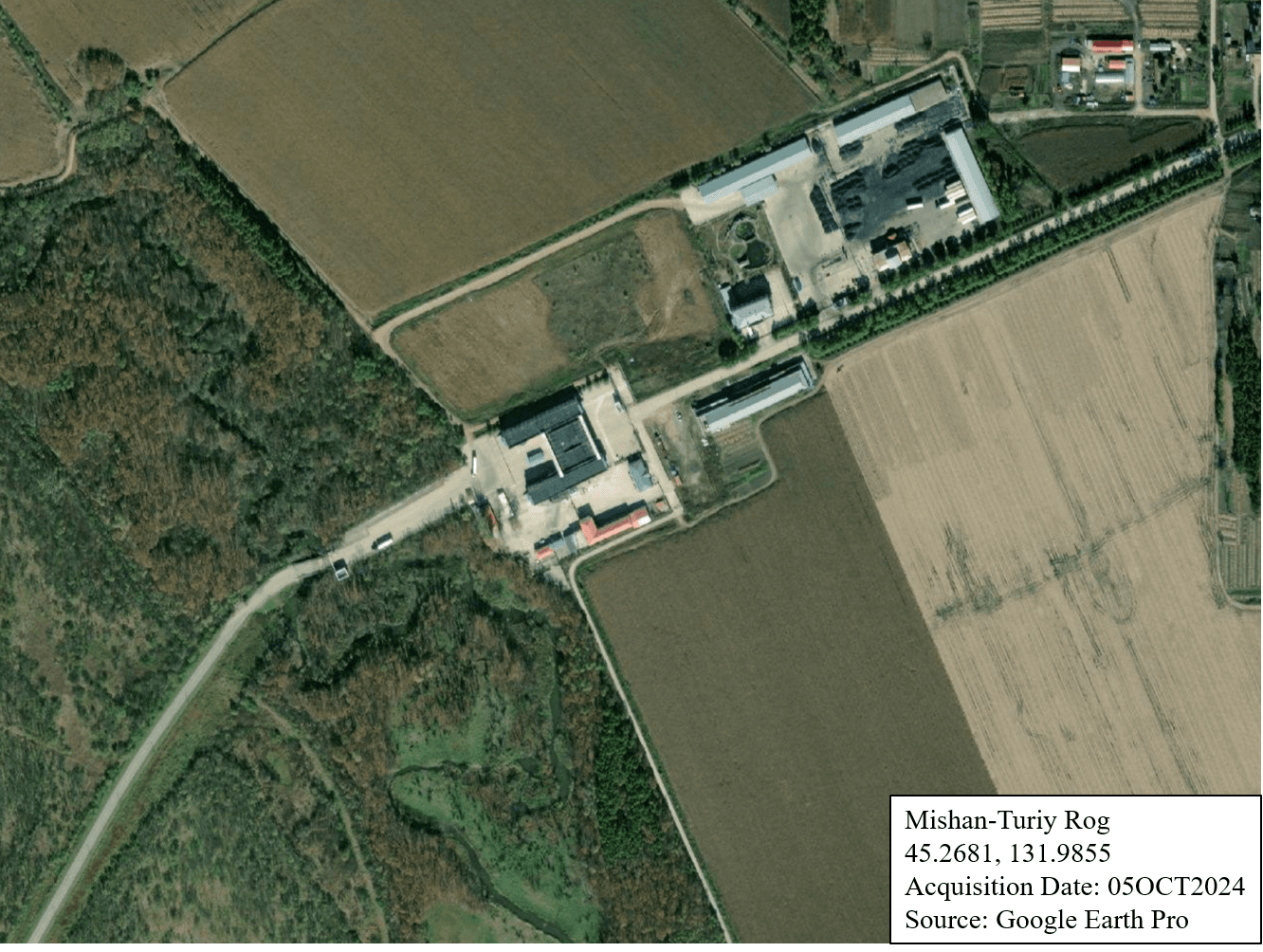

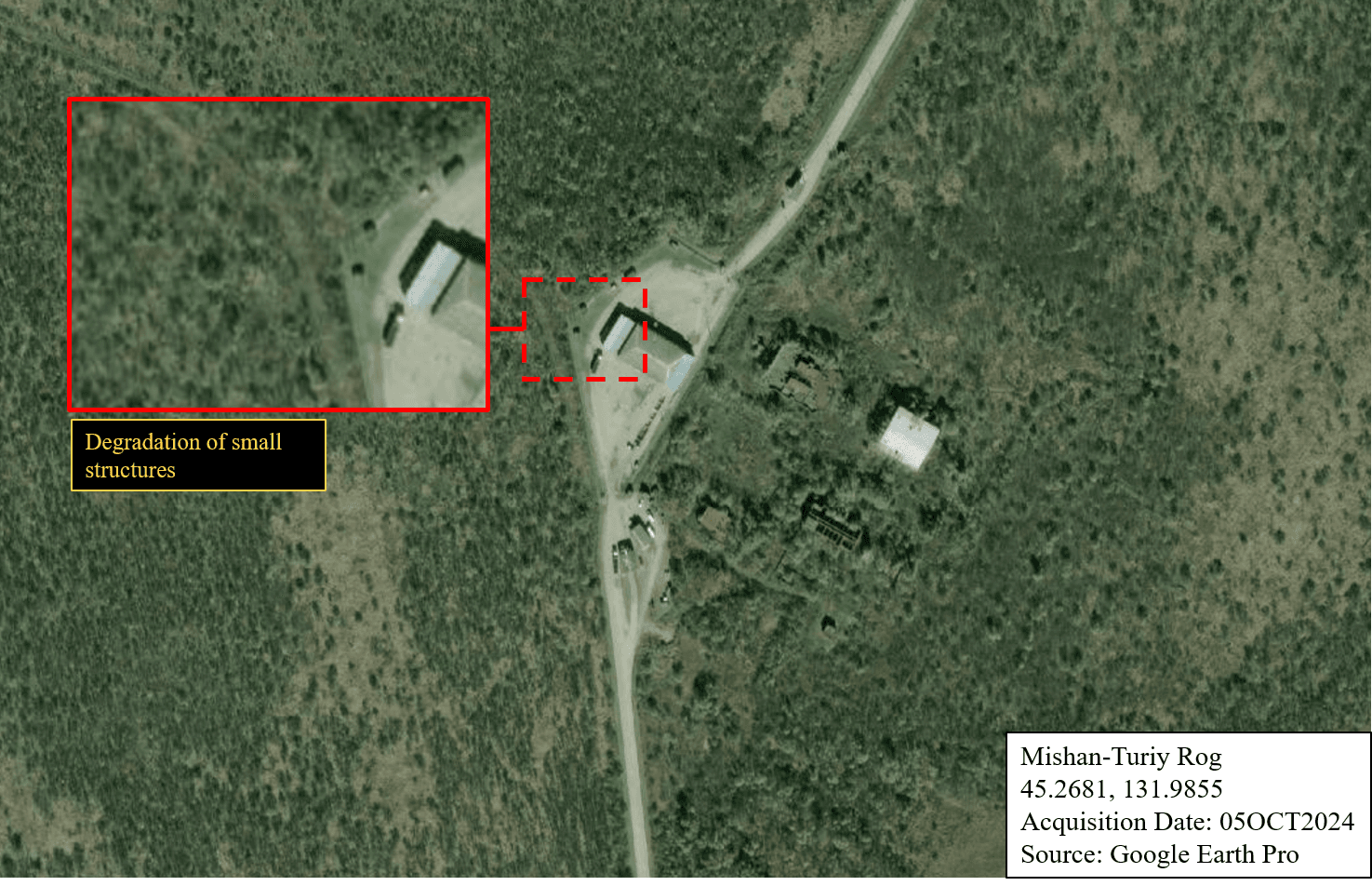

Mishan, China – Turiy Rog, Russia (Road crossing only)

The border crossing of Mishan, China and Turiy Rog, Russia has had minor increases in infrastructure between 2020 and 2024, where some small structures were constructed on both sides, possibly to contribute to the coal trade in northeastern China and southeastern Russia.

Mishan

Most of the structural increases belong to the Chinese side. Q2 2021 was the first reported change in the construction of small structures. Similarly, there was also road infrastructure construction in Q3 2024. One note is that because the Chinese side contains what appears to be an industrial site, there is a reoccurring black mound of what is highly likely to be coal deposits roughly every two years. In Q3 of both 2022 and 2024, there were major coal deposits in Mishan. Though China does not export coal to Russia, Mishan’s status as the key port of entry into the Heilongjiang province (a significant source of Chinese coal), providing access to Russia’s Vladivostok port for other exporting activities.https://www.iea.org/countries/china/coal[38]

Turiy Rog

On the other hand, there is little activity on the Russian side in Turiy Rog. There were small structures constructed in Q3 2022. It is unclear as to what these structures are or their use. In Q1 2023, it is noteworthy that the road traffic appears to be blocked. There was deconstruction in Q4 2024, where the structures constructed in Q3 2022 were removed by Q4 2024.

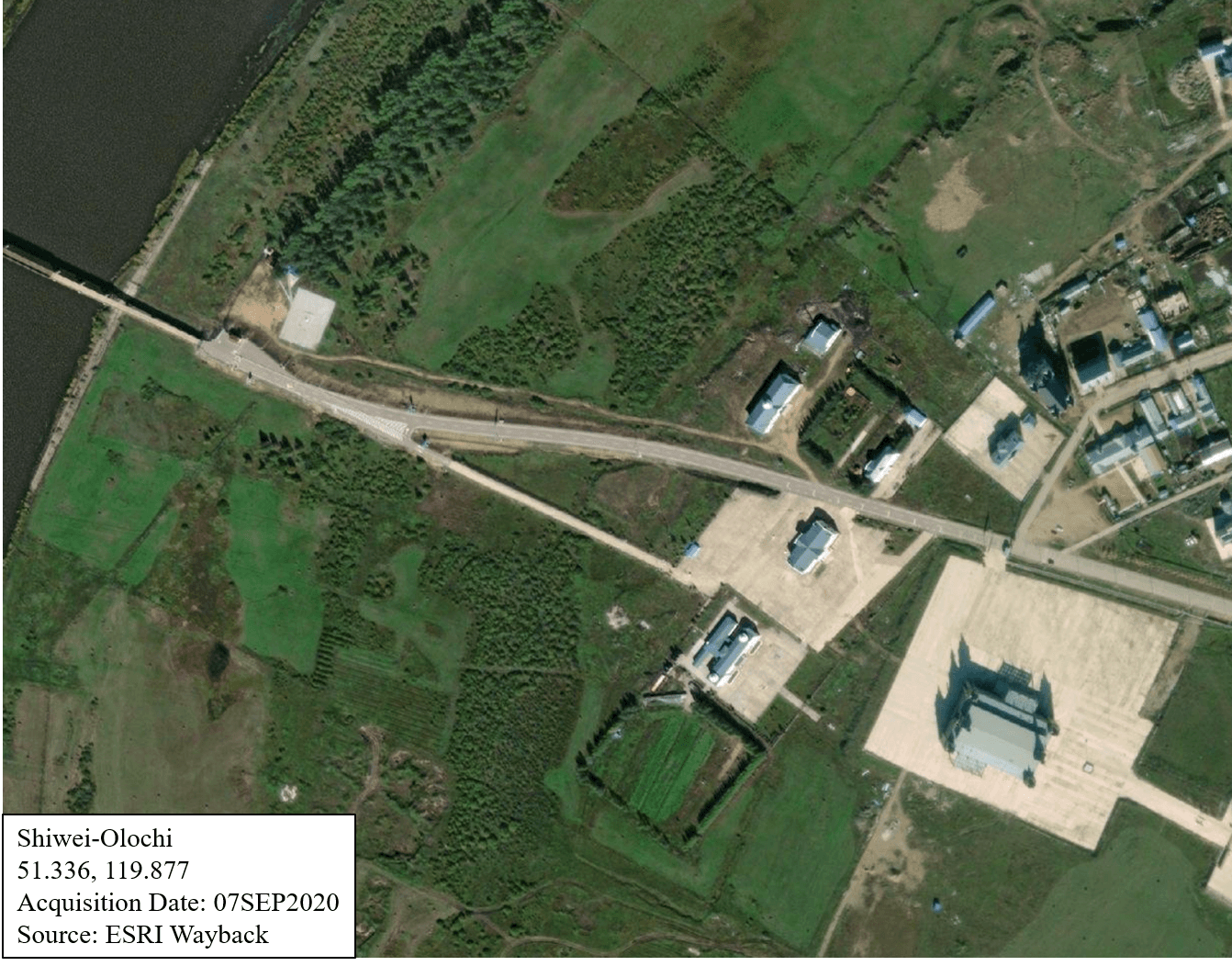

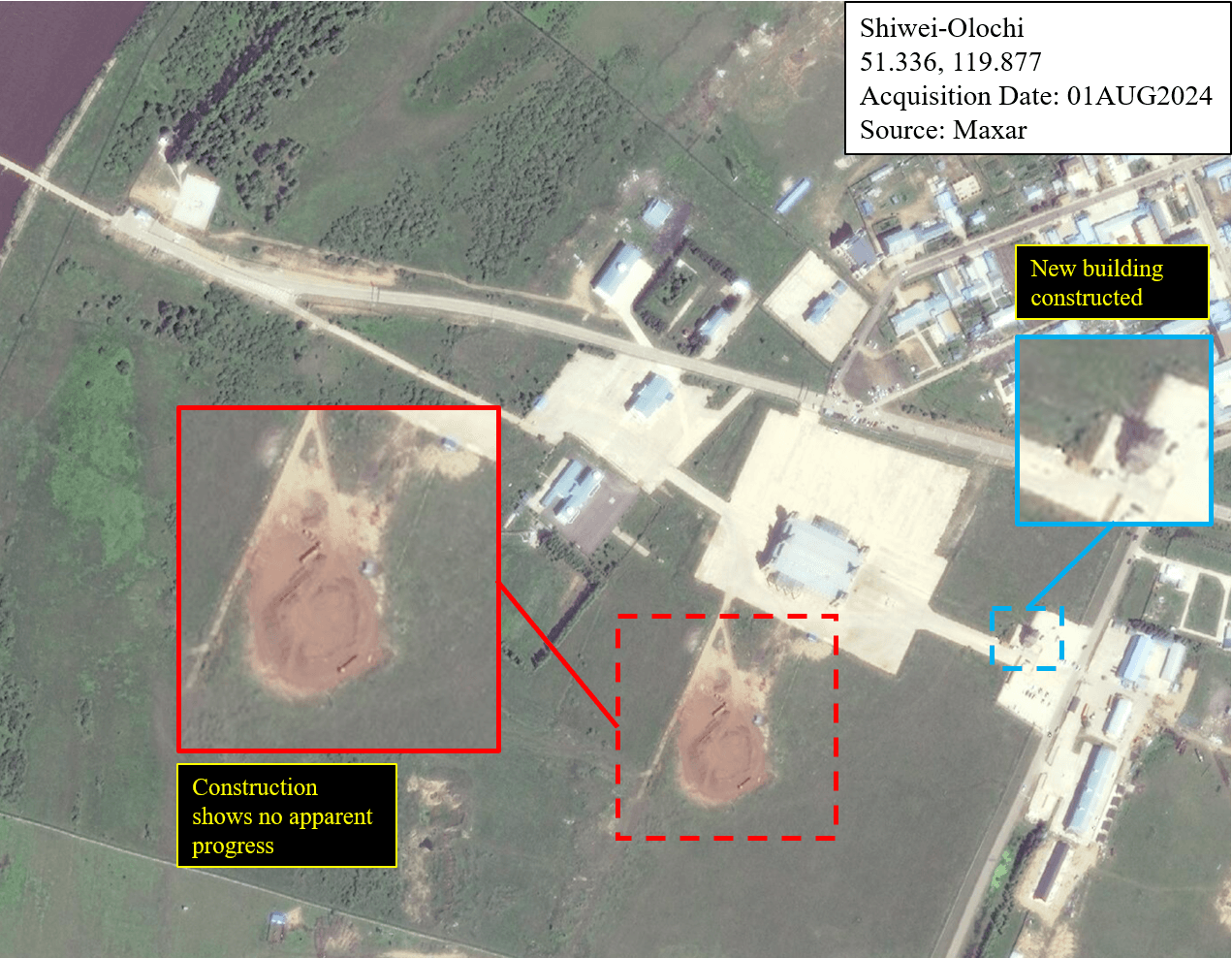

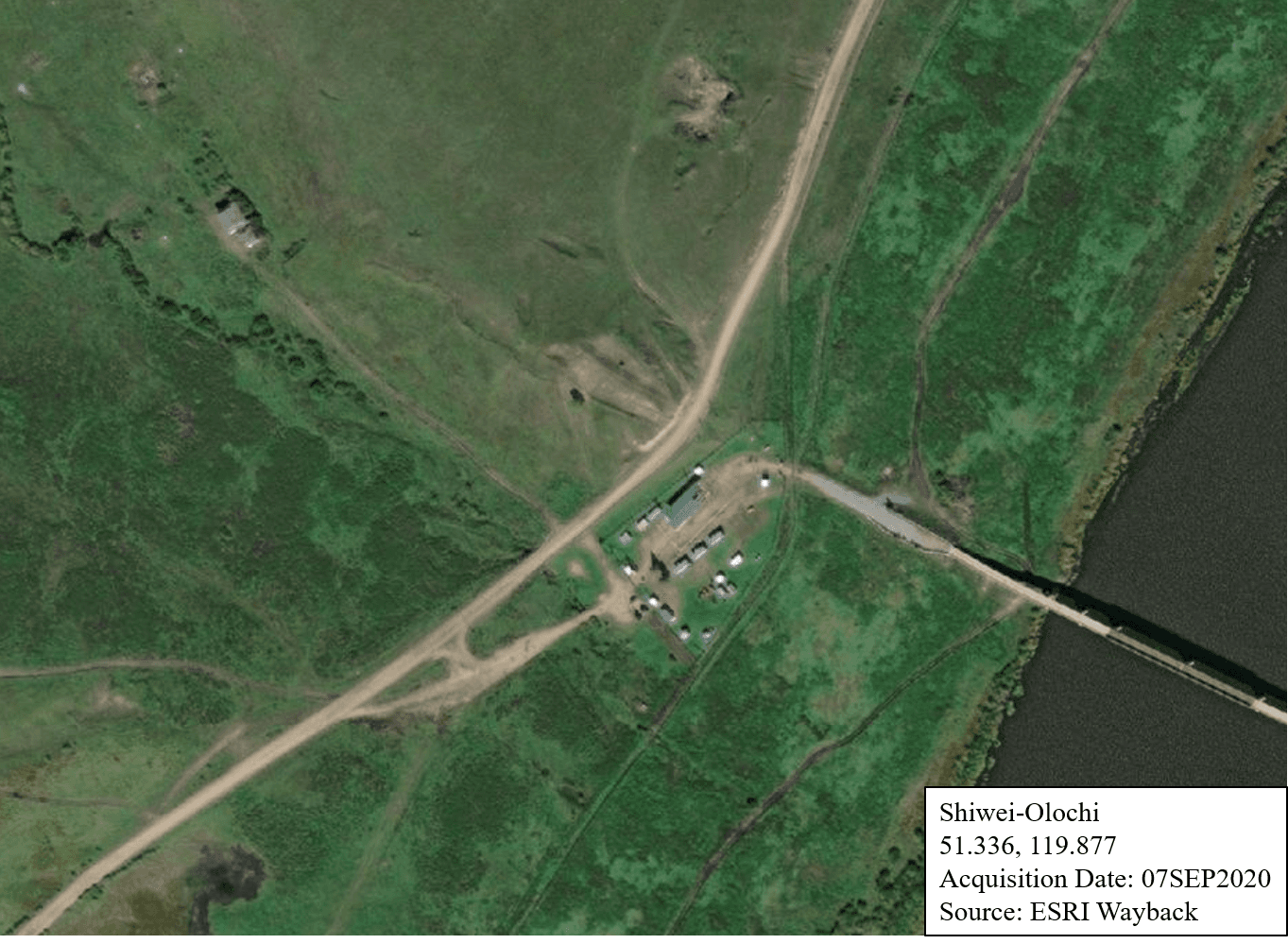

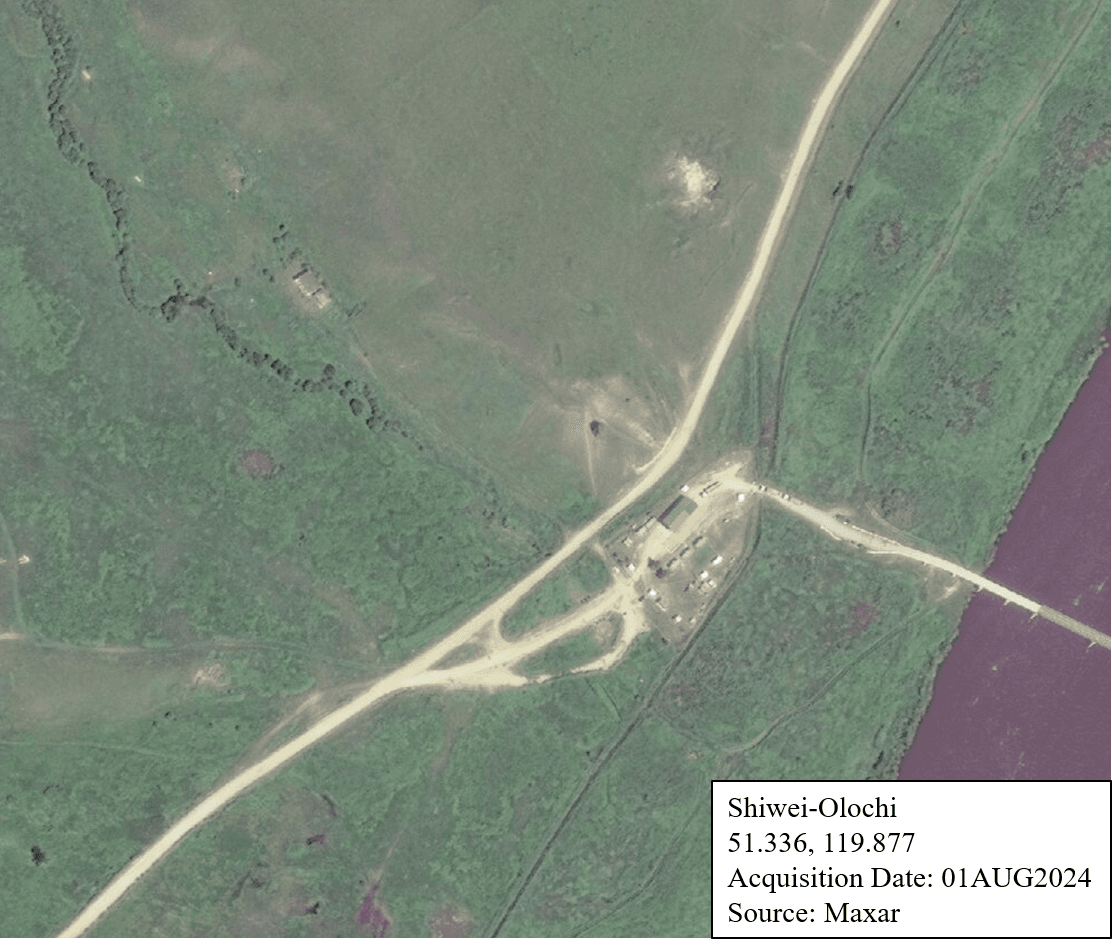

Shiwei, China – Olochi, Russia (Road crossing only)

The border crossing between Shiwei, China and Olochi, Russia saw minor road-based infrastructure development, largely around China’s visitor area construction activities and Russia’s road expansion and creation.

Shiwei

On the Chinese side, there was temporary road construction in that same quarter, which appears to be repaving; this was completed within that quarter. There was also pavement expansion in progress; however, this showed no apparent progress as of Q3 2024. It is important to note that this construction takes place near what appears to be a visitor center or border inspection station.

Olochi

On the Russia side, Q4 2023 showed some road construction in progress, with a lane addition on the main cross-border road, as well as some development of smaller frontage or spur roads. These smaller roads parallel the road that intersects with the main cross-border road at a T-shaped intersection, traveling northeast/southwest within Russia.

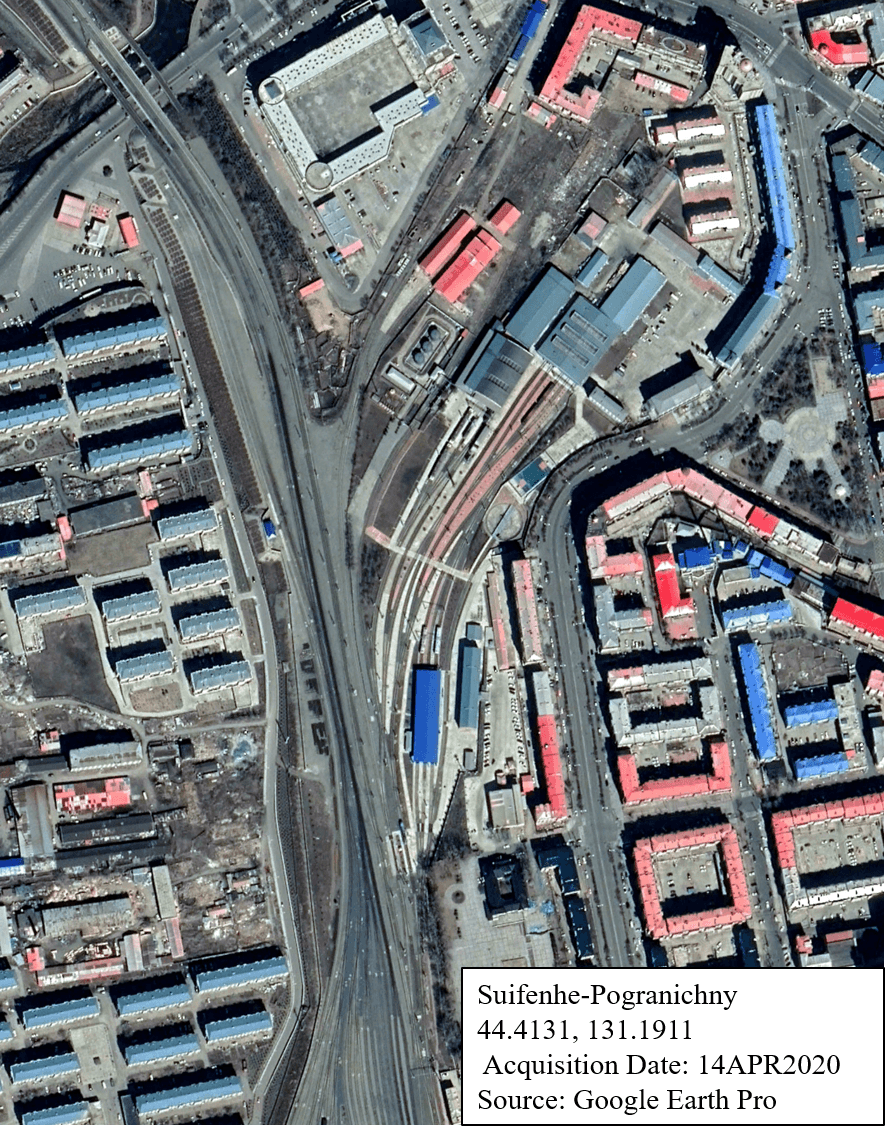

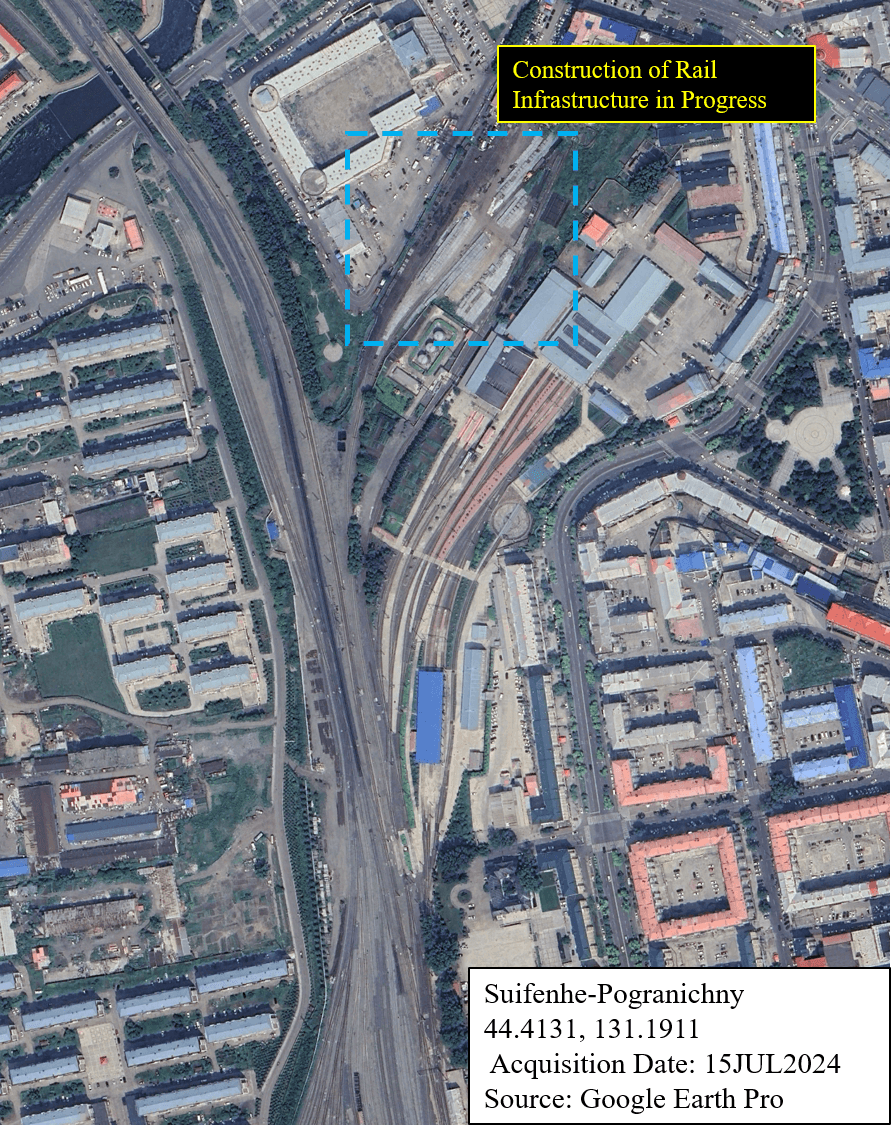

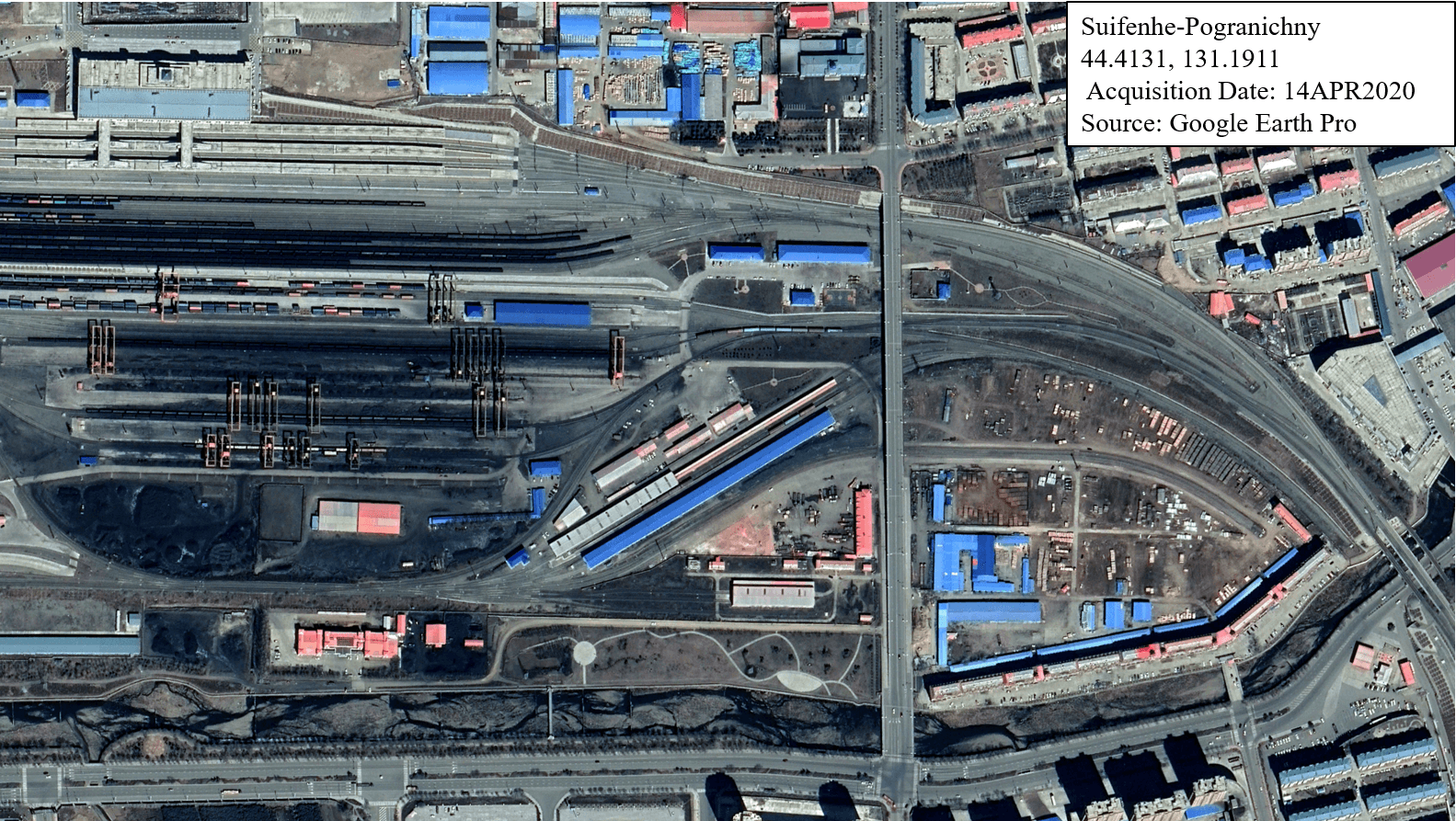

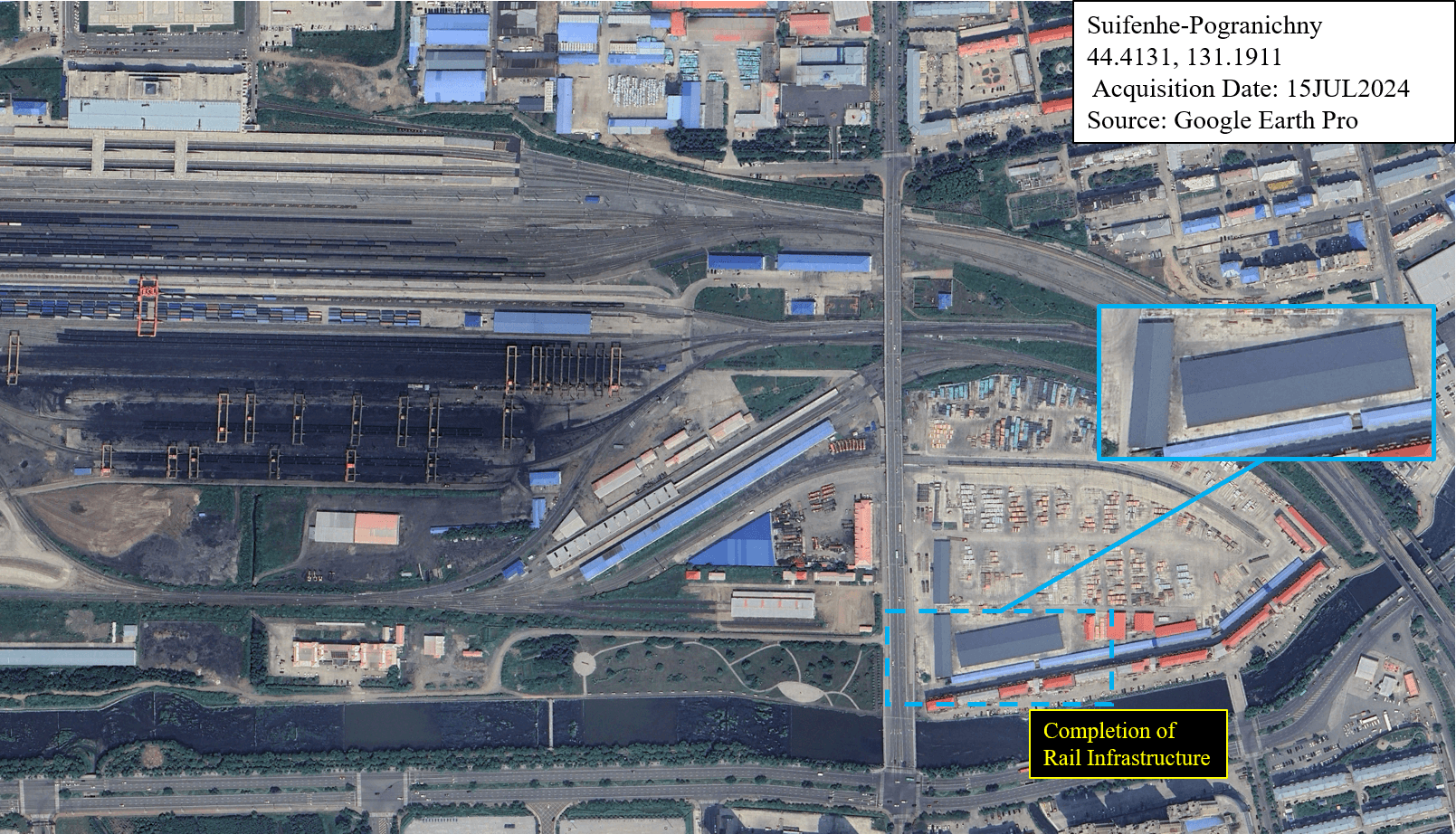

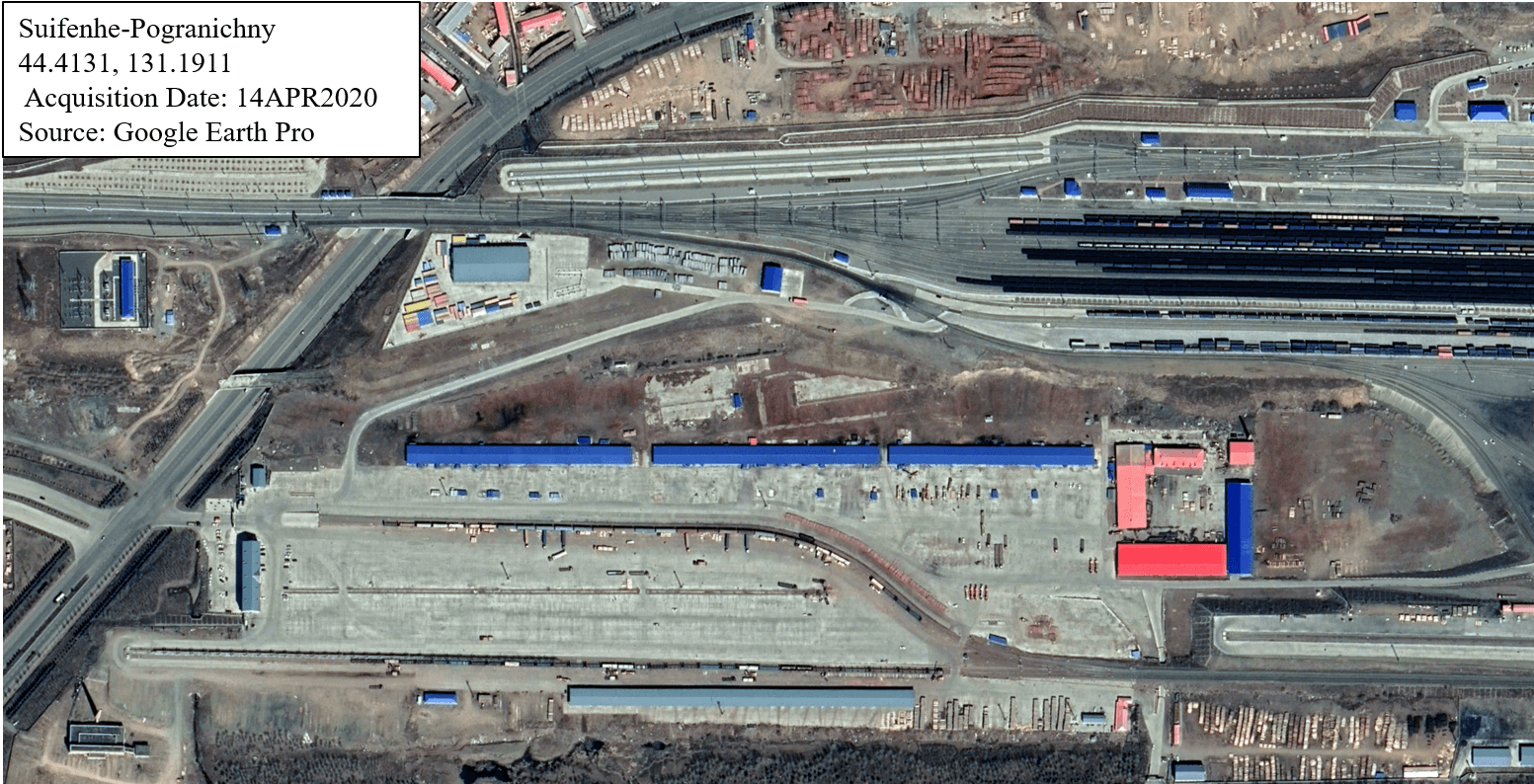

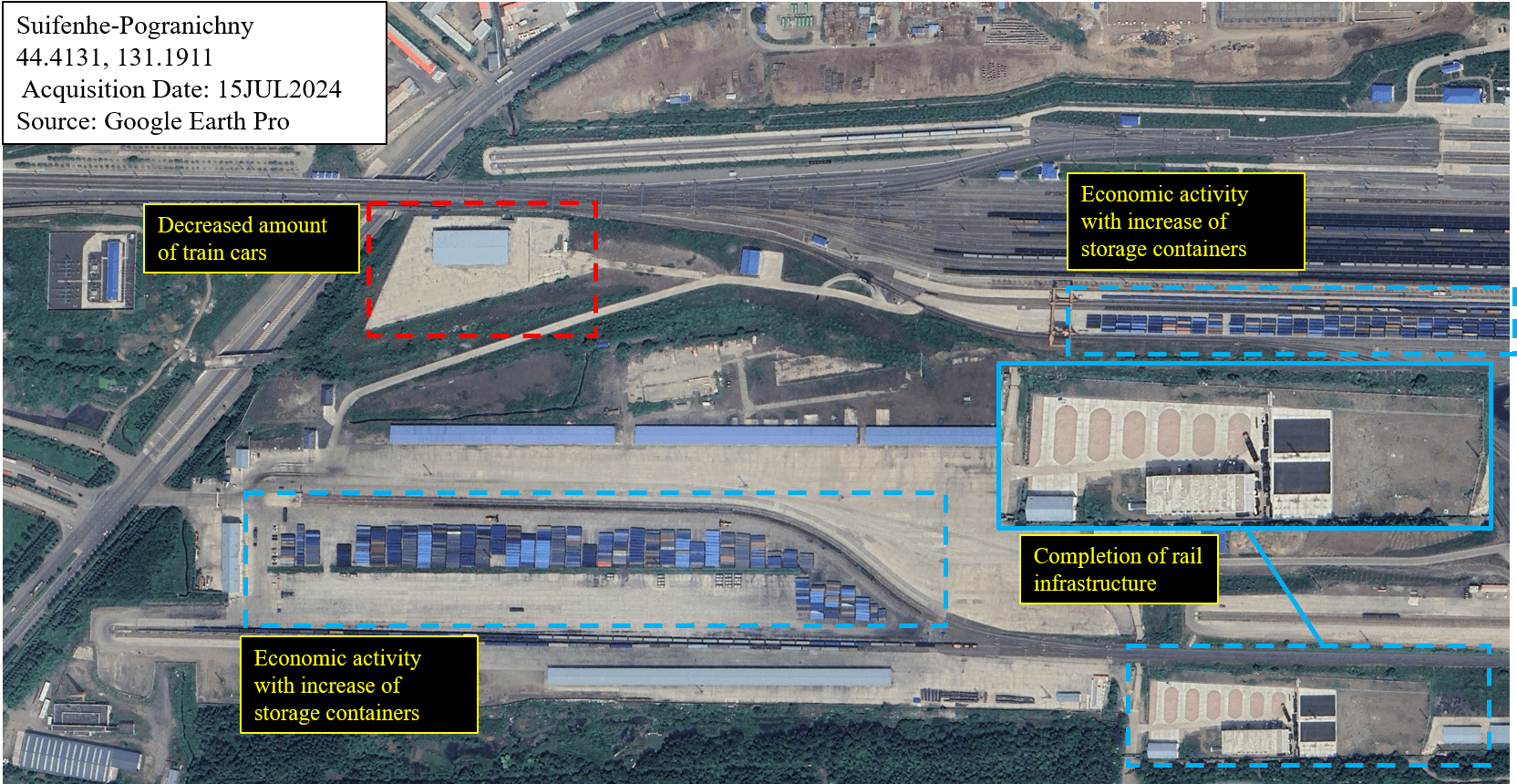

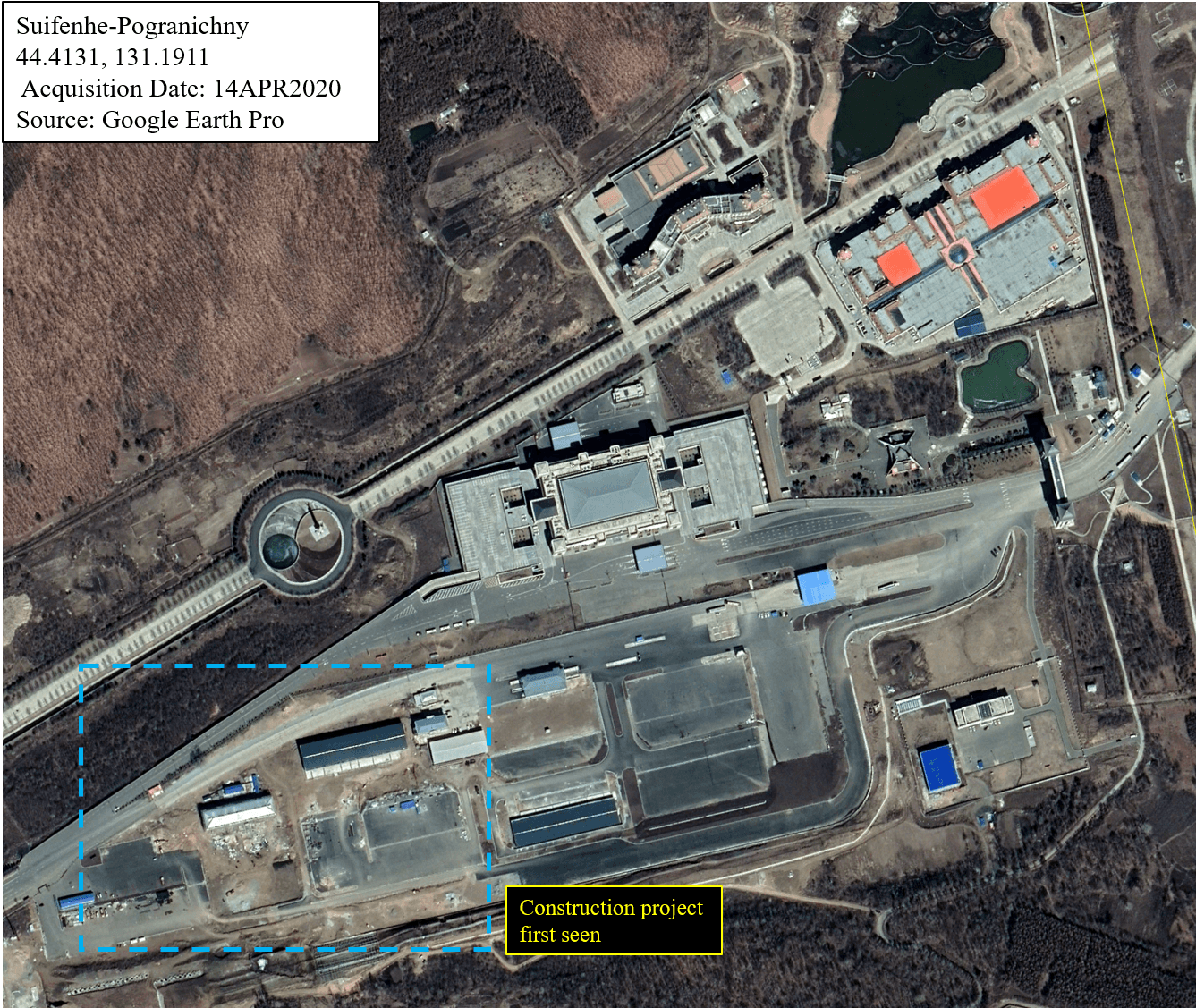

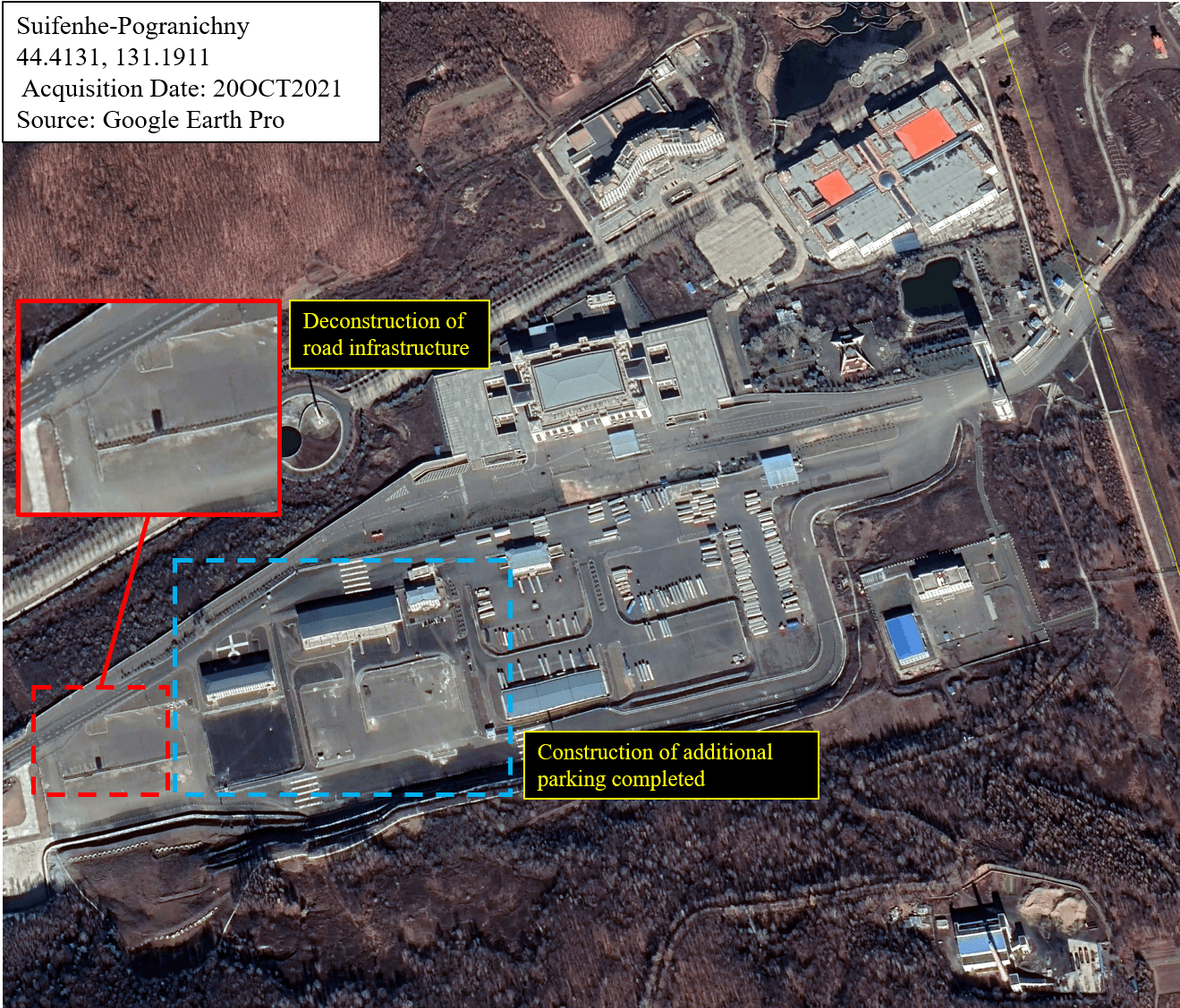

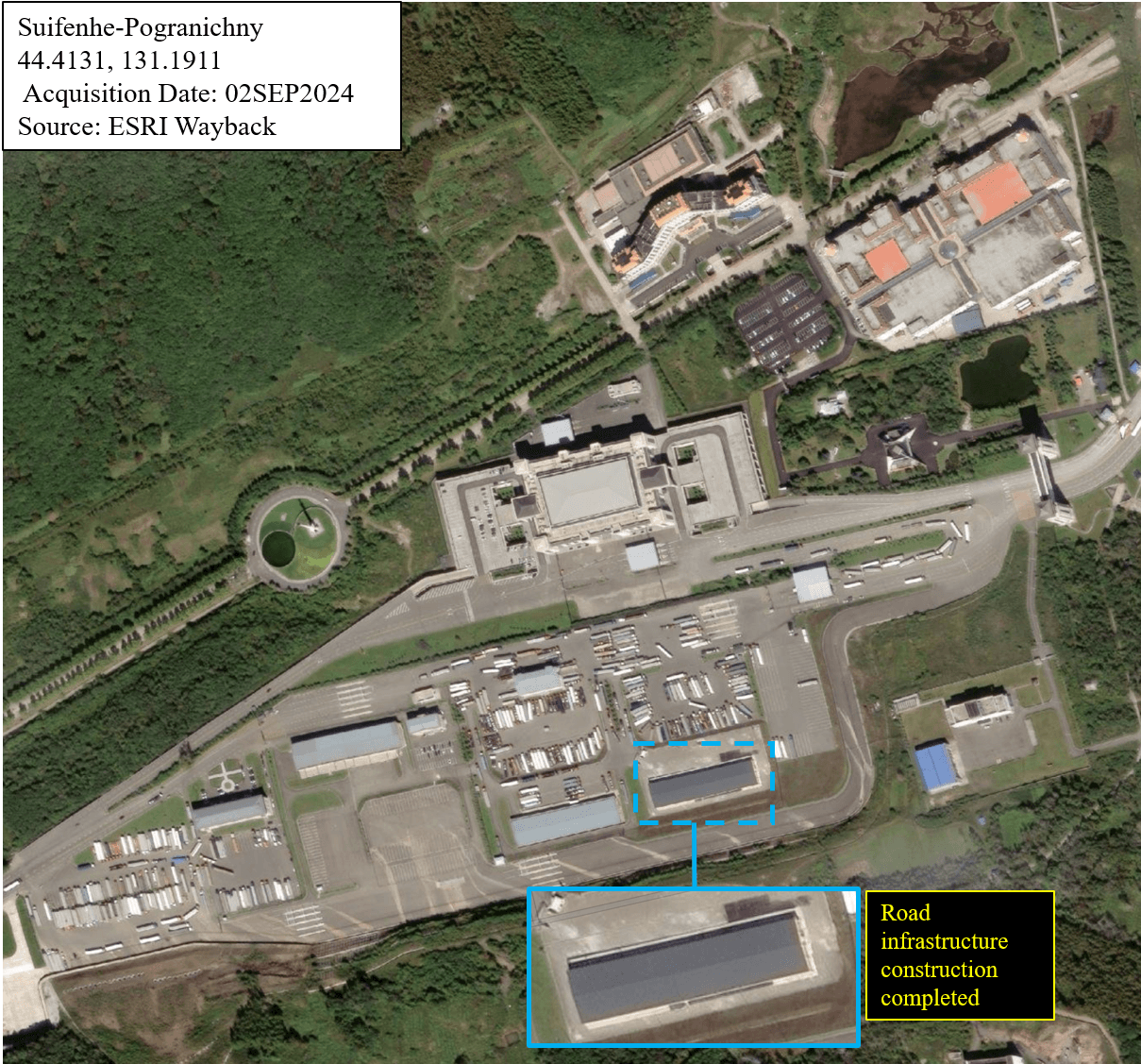

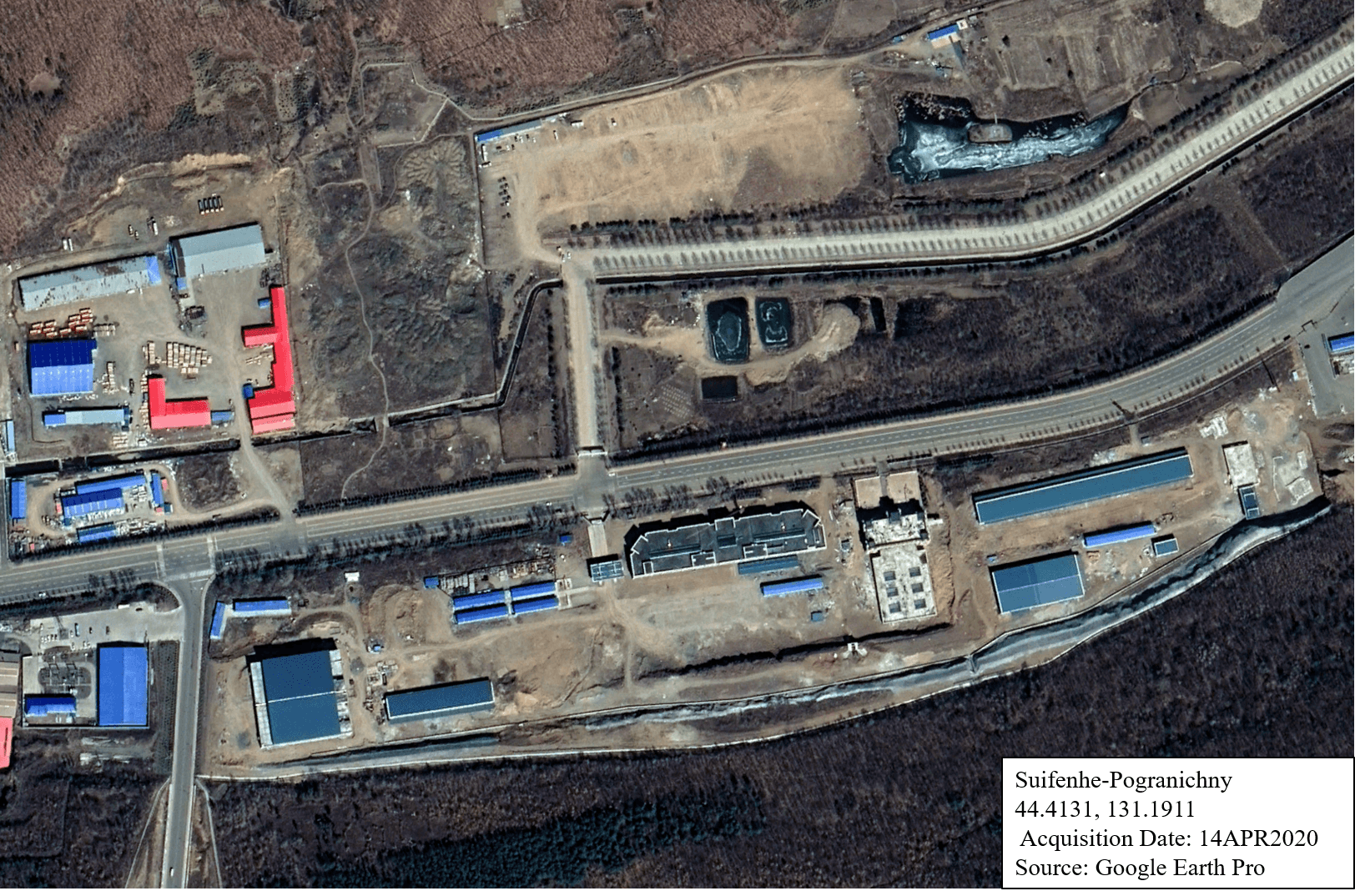

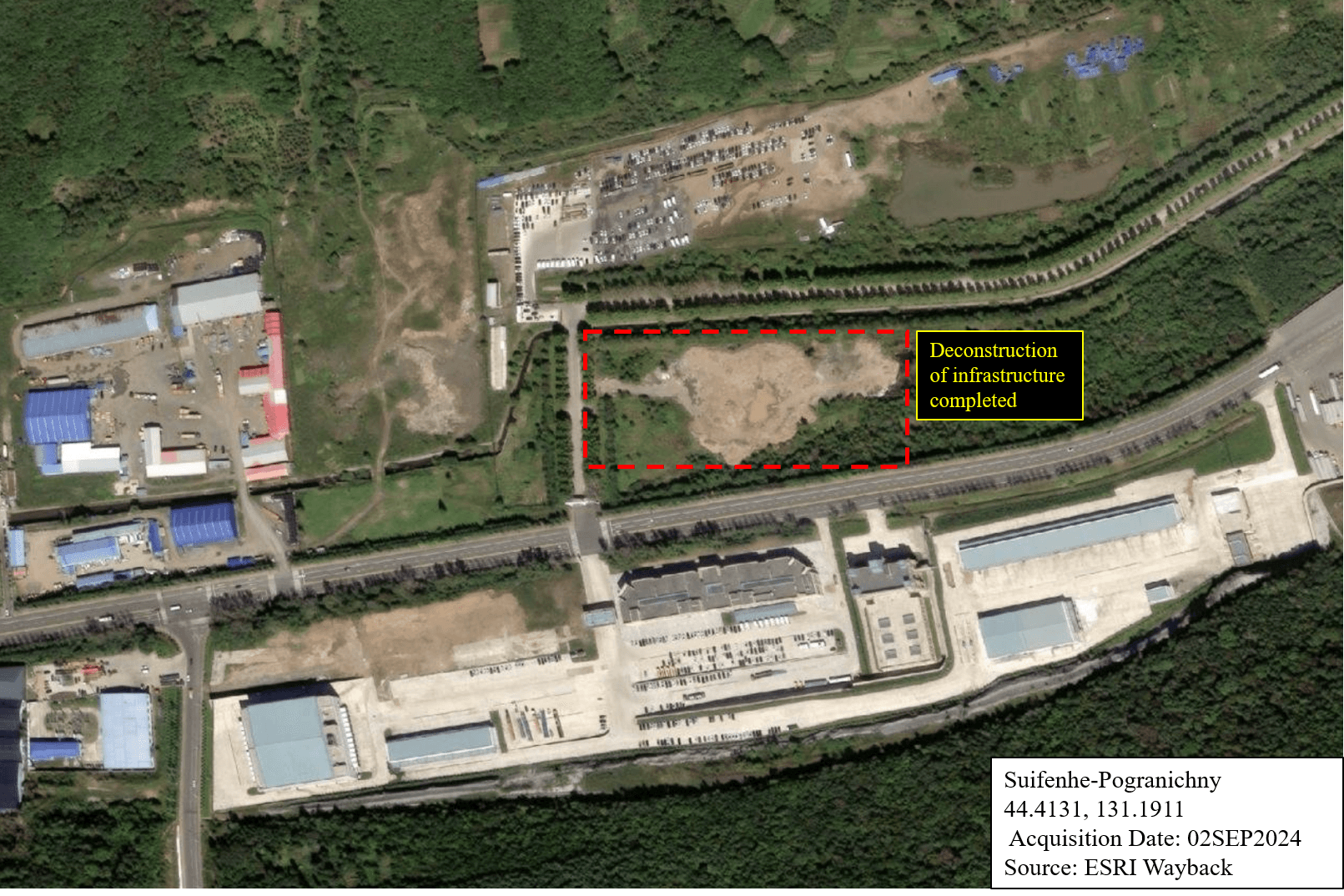

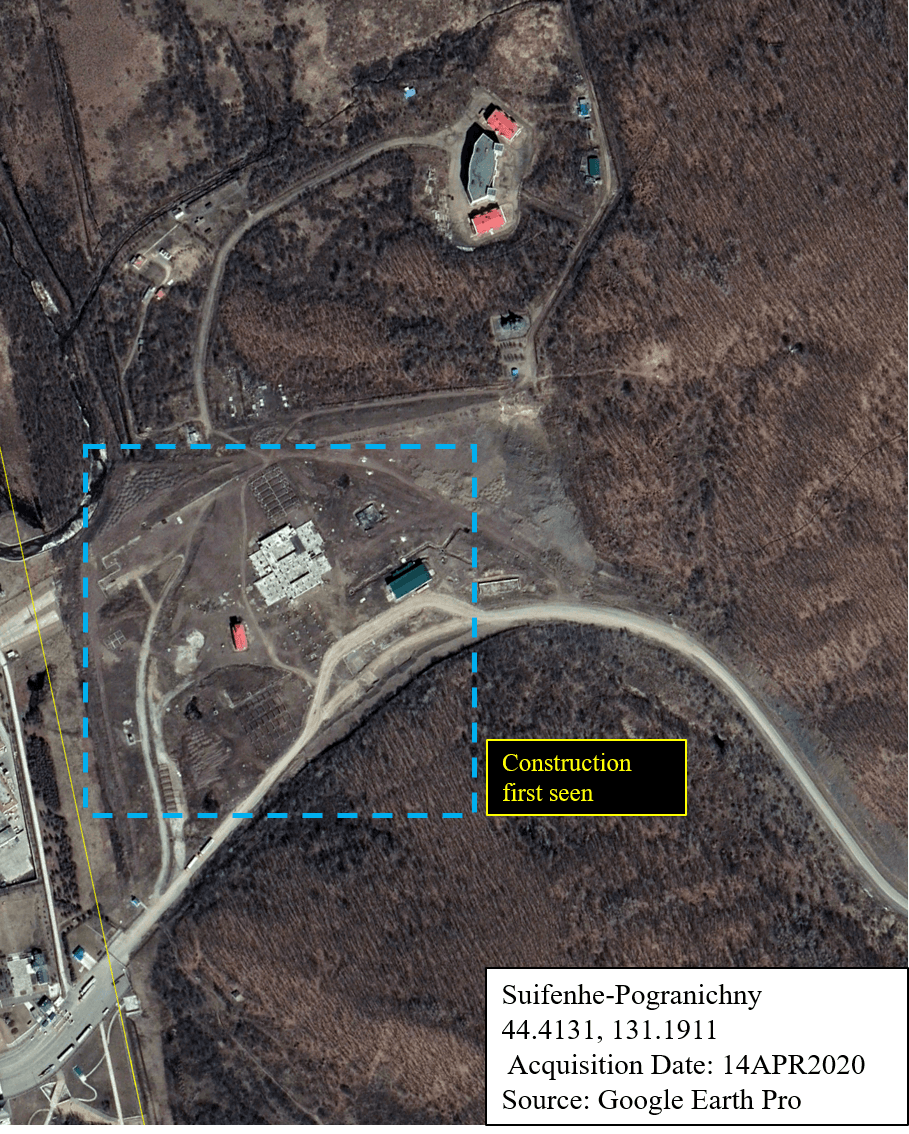

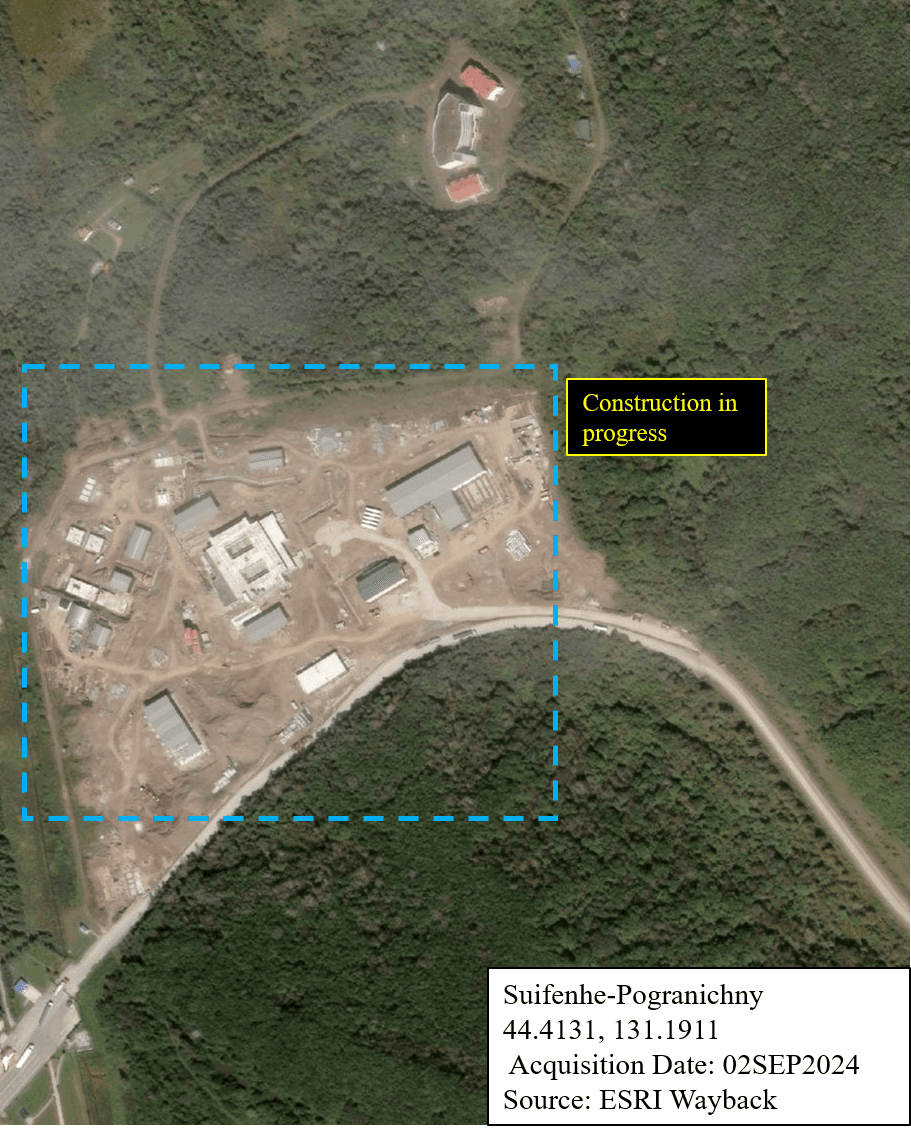

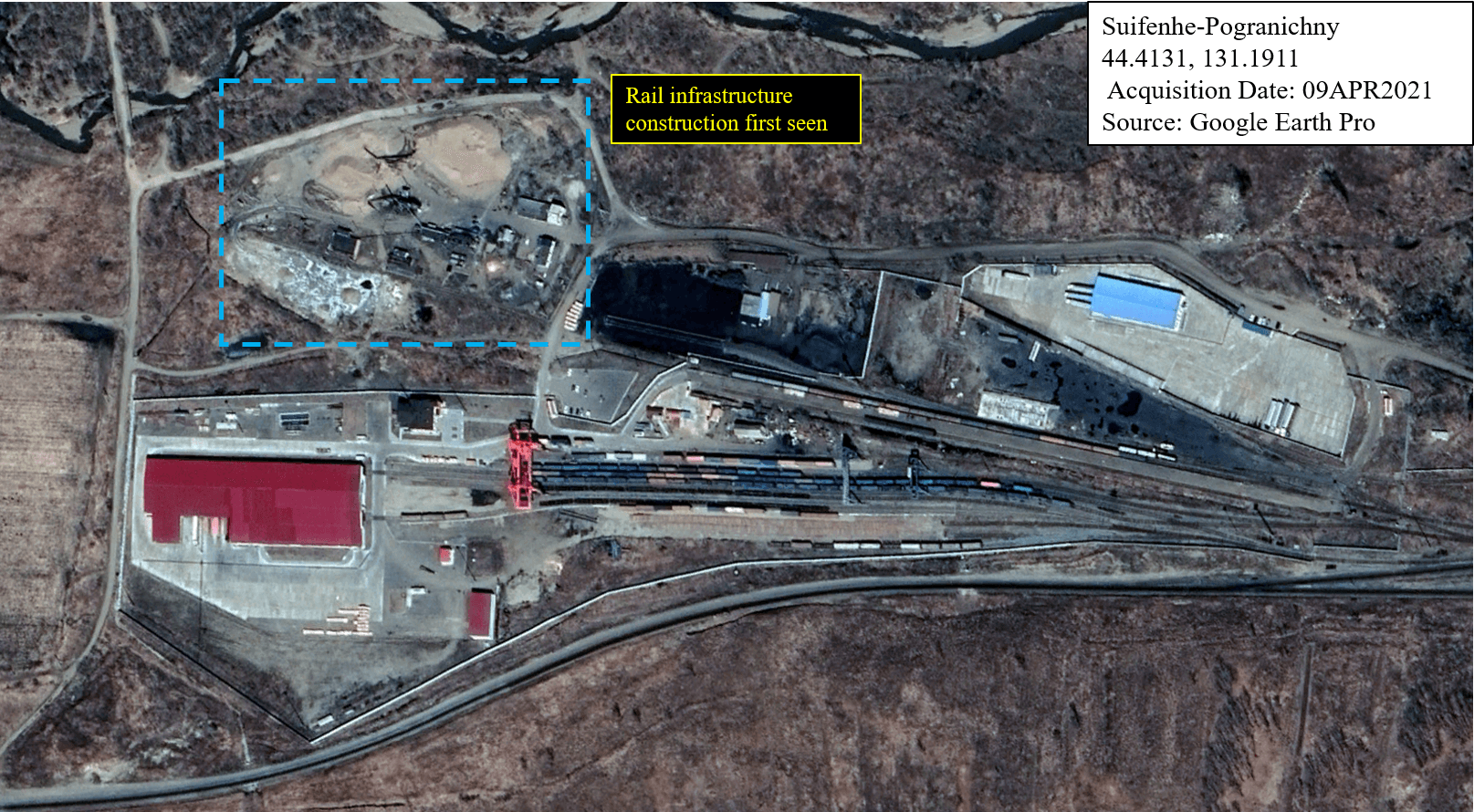

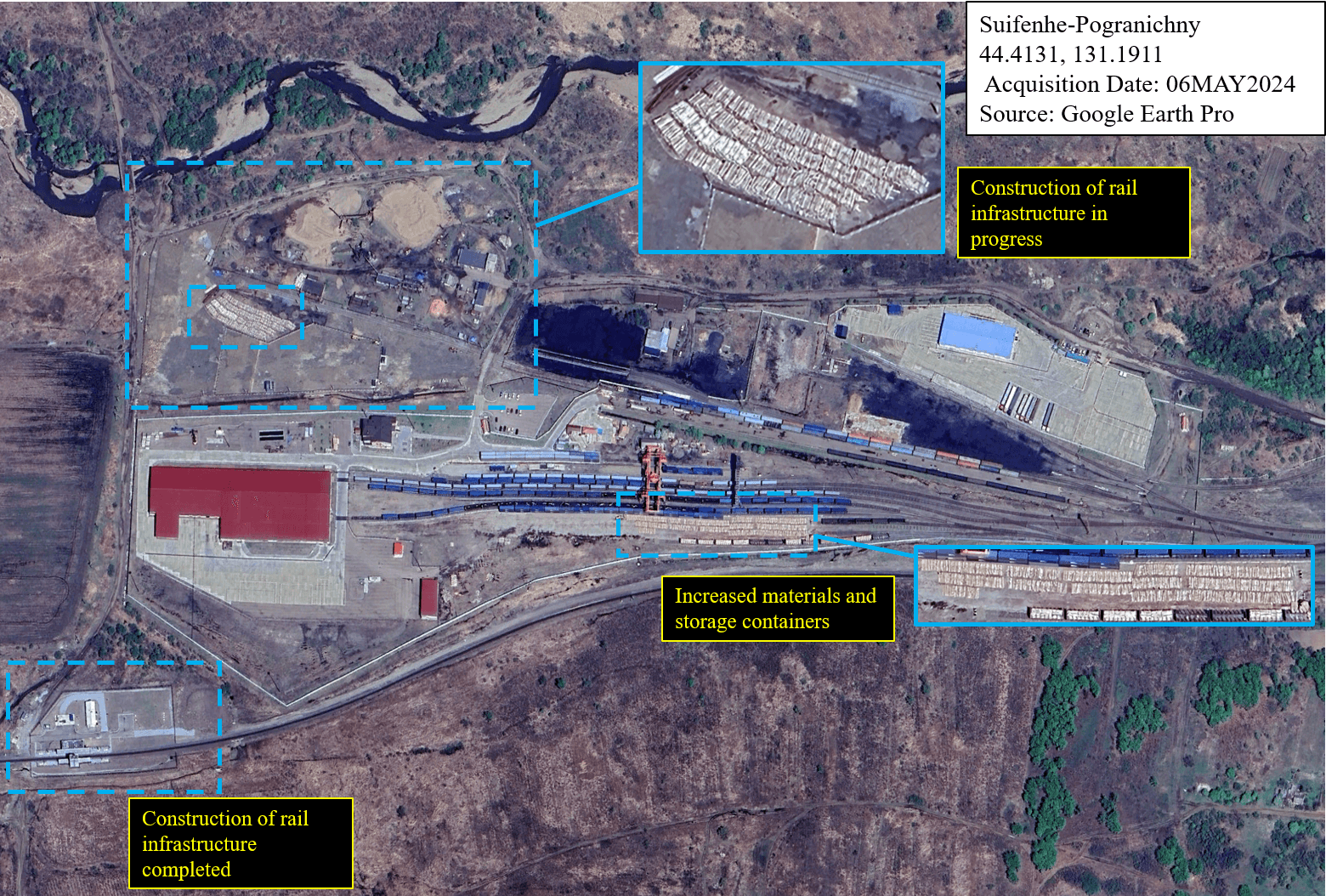

Suifenhe, China – Pogranichny, Russia (Both road and rail crossing)

The border crossing between Suifenhe, China and Pogranichny, Russia saw an increase in both road and rail infrastructure throughout the period of 2020 and 2024, primarily to increase material storage and transport capacity.

Suifenhe

On the Chinese side, most rail changes occurred in two adjacent sections. In Q2 2020, two warehouses were under construction. By Q4 2021, these warehouses were completed, with additional foundational construction of another warehouse in progress. In that same quarter, a smaller warehouse was demolished. As of Q3 2024, a larger warehouse was completed, with two others torn down. Despite the construction of new rail sections branching off from the main line for storage purposes, the amount of cargo cars present slightly decreased from Q4 2021, from around 350 to 300.

Pogranichny

Regarding Chinese road infrastructure, imagery showed an increase in infrastructure to park, unload, and pass vehicles through at the border crossing. The first imagery of the aforementioned period is taken from Q2 2020. In this quarter, there was no observed traffic, and there were construction projects in progress. An additional parking lot was constructed by Q4 2021, with other minor road infrastructure deconstructed. By Q3 2024, a warehouse was constructed, and there was also a heightened amount of traffic in the area, from about 110 semi-trucks in Q4 2021 to over 200 in Q3 2024.

Suifenhe Storage

Further west into the Chinese side of the border, imagery primarily shows deconstruction around what is very likely an industrial storage site (due to the presence of warehouses and construction materials), possibly due to a decrease in other construction activities nearby. Between Q4 2020 and Q4 2021, there was development of road infrastructure, namely parking lots, around storage facilities. This was accompanied by minor infrastructure removal in the same vicinity. However, as of Q2 2024, a section of infrastructure was undergoing deconstruction north of the main cross-border road. In Q3 2024, the aforementioned deconstruction was complete, and there was further degradation of smaller dirt roadways to the west of this site.

Pogranichny Road

Additionally, the Russian side of the border saw road-based building infrastructure, with a single site first noticed in Q2 2020. In all images collected beyond the first image (Q4 2020, Q4 2021, and Q3 2024), this construction expanded, with the original buildings accompanied by more foundations, and ultimately 13 confirmed buildings on the site by Q3 2024. The imagery appears to show this site still under construction as of that quarter. Though the purpose is unknown, these buildings’ adjacency to the border and their foundations as nonresidential sites likely make them border inspection or customs offices, paralleling these existing counterparts on the Chinese side.

Pocgranichny Rail

Furthermore, the Russian side’s rail section saw construction to likely increase the rail-based raw material transport capacity. In Q2 2021, construction was first seen at an existing construction material storage site adjacent to the rail lines. By Q2 2022, construction continued at the site, and two small supporting warehouses were under construction just south of the rail lines. As of Q2 2024, the two warehouses were completed, and at both the storage site and directly next to the tracks, additional construction materials were present.

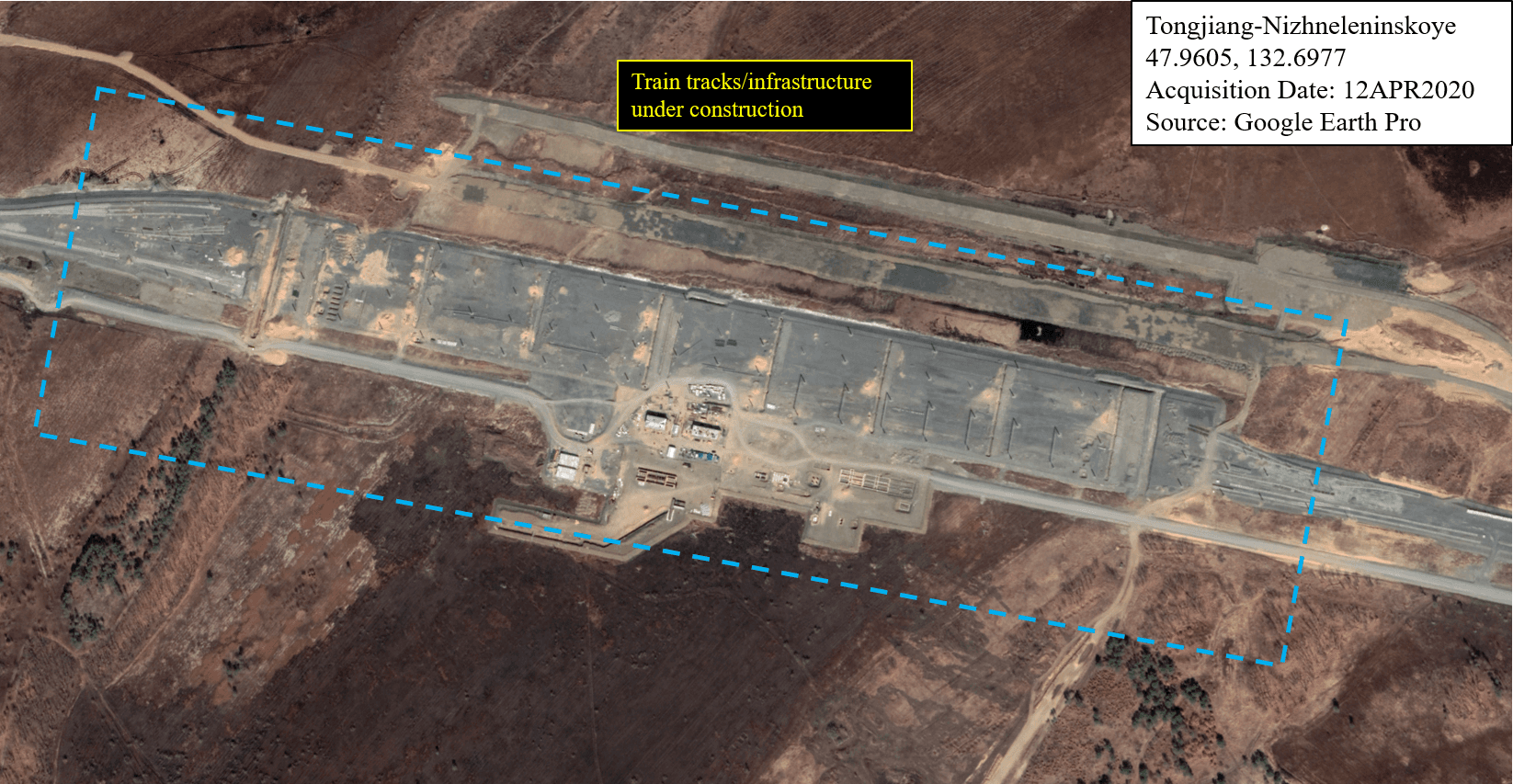

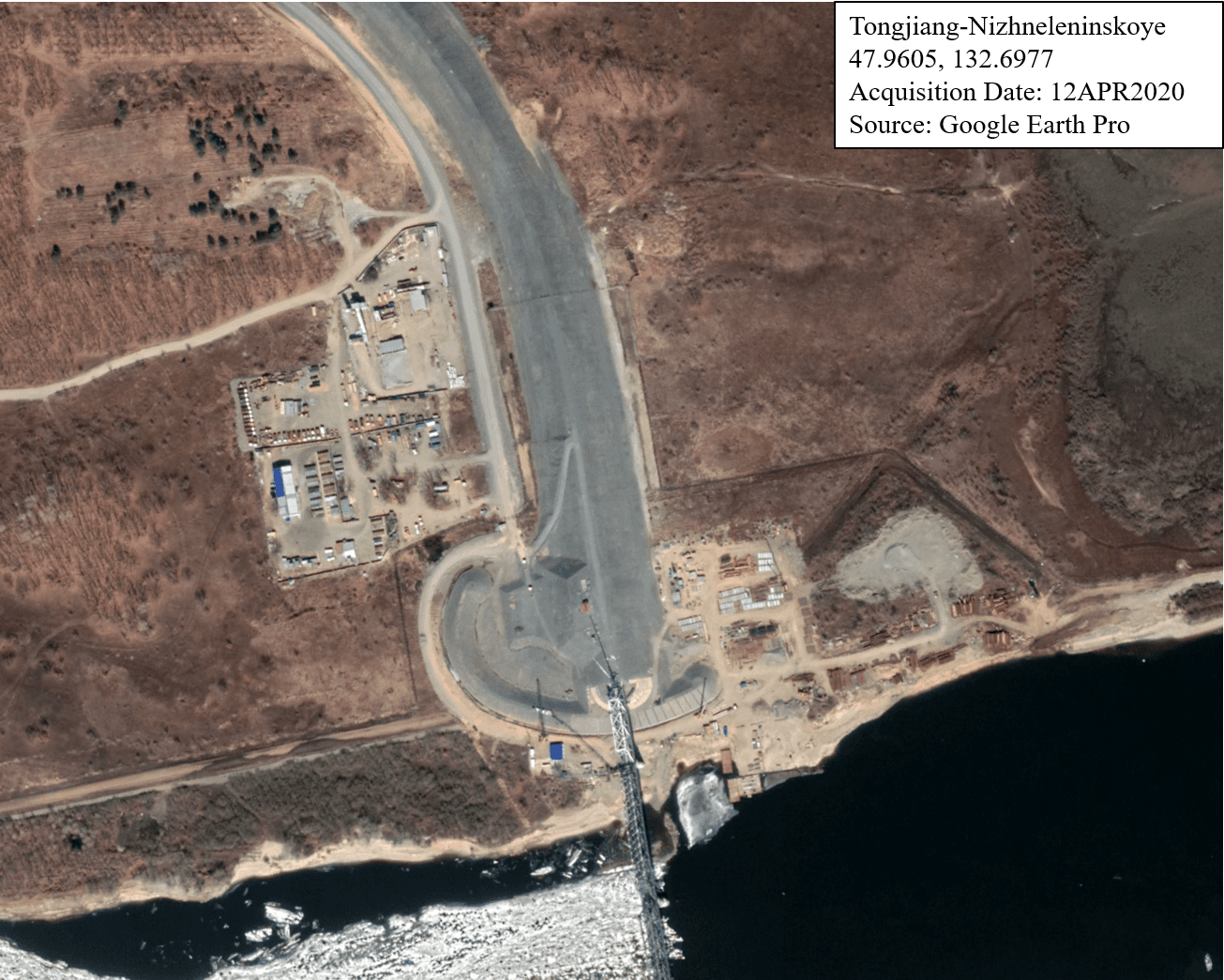

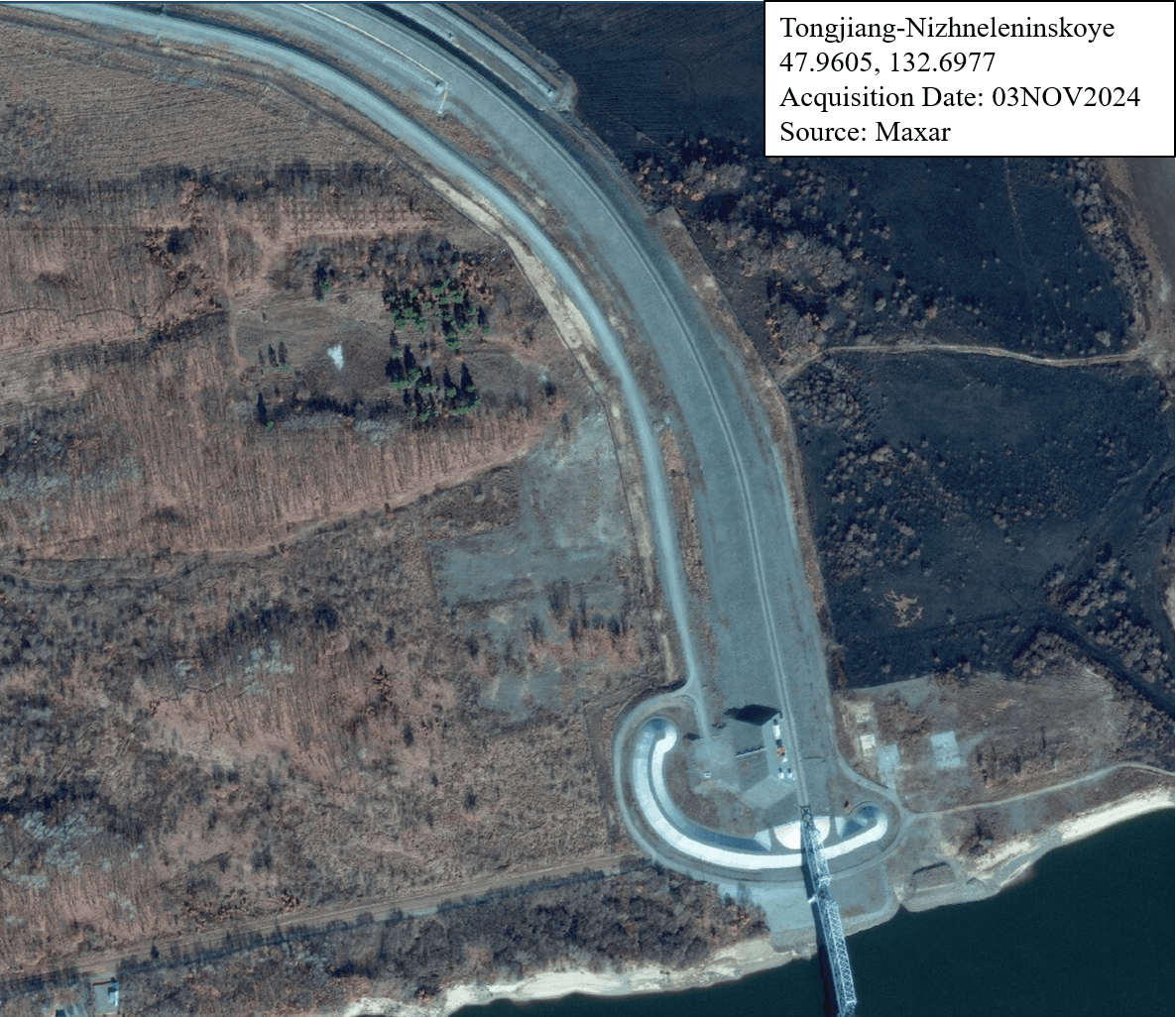

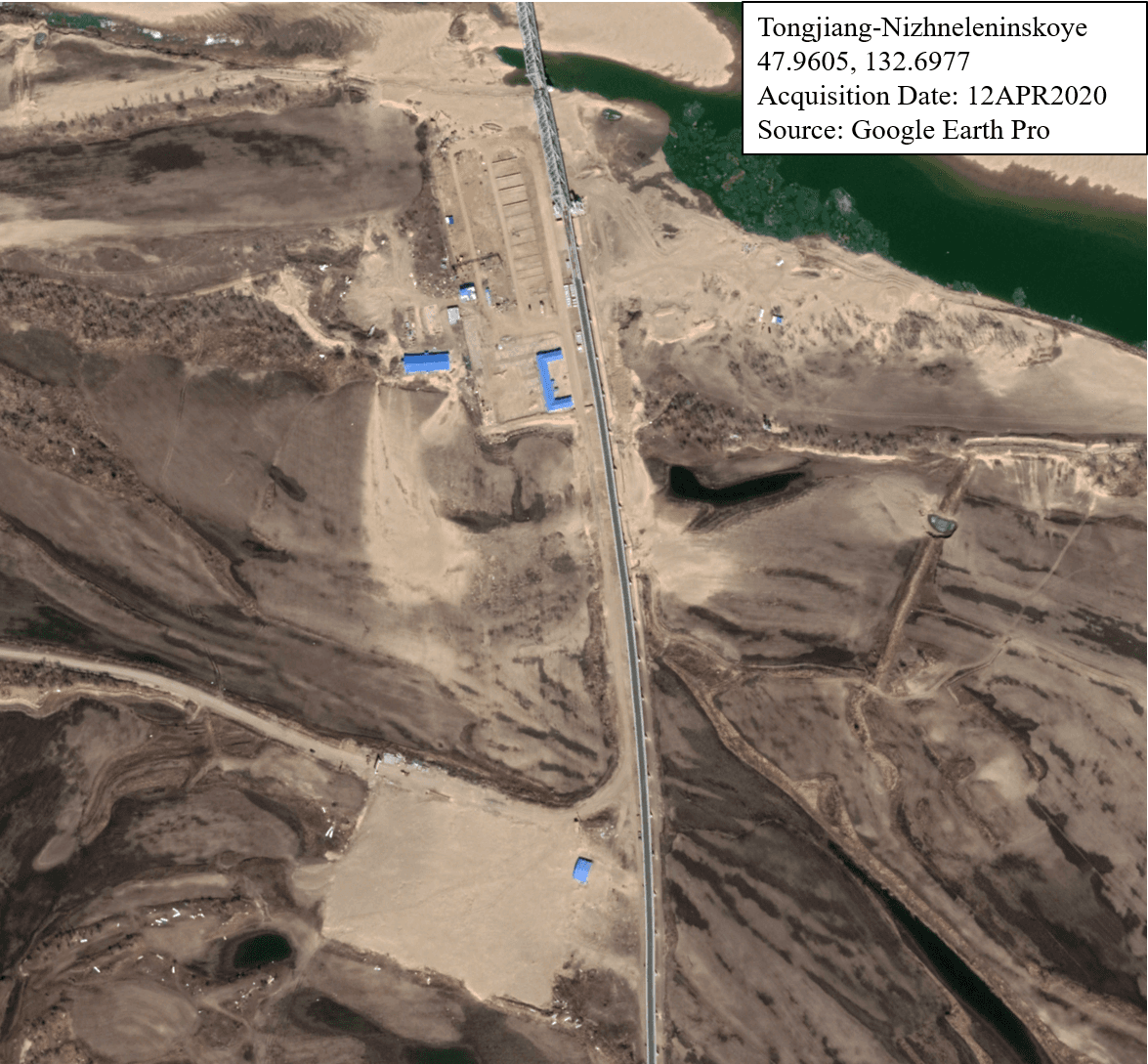

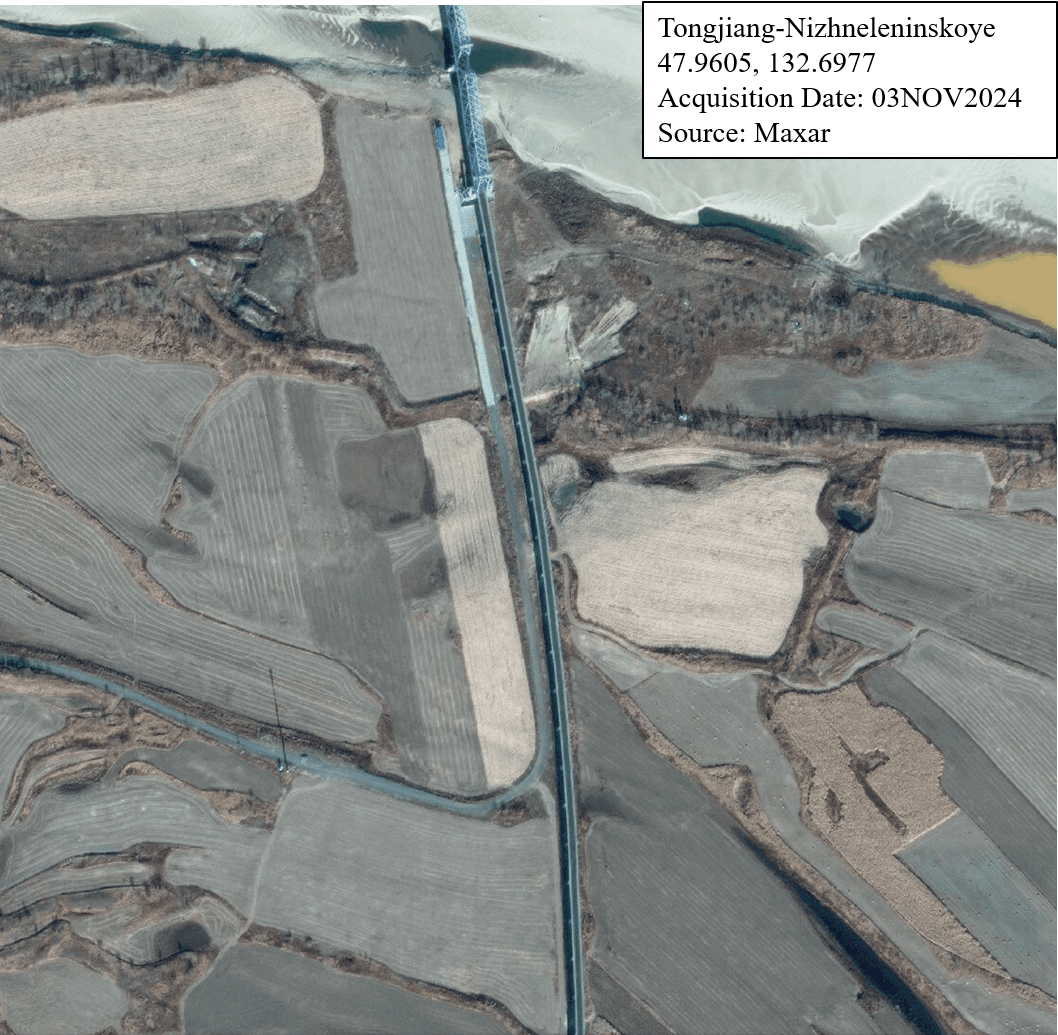

Tongjiang, China – Nizhneleninskoye, Russia (Both road and rail crossing)

The border crossing between Tongjiang, China and Nizhneleninskoye, Russia significantly increased the development of rail-based infrastructure, and slightly increased development of road-based infrastructure between 2020 and 2024, likely increasing the ability to store train cars within Russia.

Tongjiang

All major developments occurred on the Russian side of the border. In Q2 2020, ongoing construction of a multi-track rail stop was seen and was completed by Q2 2022. By constructing eight rails diverging from the two main lines, Russia can now stage up to four times the original capacity of cargo cars at this stop. Further towards the border, a construction site and a small building near the highway bridge were found to be deconstructed in Q4 2023. Also, there was a small dock previously present beneath the bridge, and it was replaced with sand or a similar material filling the land.

Nizhneleninskoye

On the Chinese side of the border, there was little activity that took place. The only change occurred between Q2 2020 and Q2 2022 with the deconstruction of small-scale road infrastructure located near the highway bridge.

Assessments Based on Open-Source Information

In using OpenRailwayMap, the team made certain assessments for the following locations that corroborated imagery:

- Hunchun, China – Kraskino, Russia: Data indicates the presence of dual gauge tracks at the border crossing with a bogie exchange or transshipment station at the Hunchun station.https://www.openrailwaymap.org[39]

- Manzhouli, China – Zabaykalsk, Russia: The Manzhouli-Zabaykalsk border crossing operates with independent 1435mm and 1520mm gauge tracks, suggesting largescale bogie exchange or transshipment operations.Ibid[40] There is an absence of dual gauge tracks.Ibid[41]

- Suifenhe, China – Pogranichny, Russia: Dual gauge tracks are present, beginning just after the Grodekovo-2 station and extending into China at the Suifenhe station.Ibid[42] Additionally, single tracks of both 1435mm and 1520mm exist in the Suifenhe station.Ibid[43] The presence of dual gauge tracks in several areas around the border crossing suggests that both Russian and Chinese trains can operate in certain sections without requiring immediate cargo transfer. However, both stations are largely comprised of their respective gauges, indicating rail freight must undergo bogie exchange or transshipment operations once it has reached either station.Ibid[44]

- Tongjiang, China – Nizhneleninskoye, Russia: As previously stated, this border crossing largely consists of dual gauge tracks.Ibid[45] Unlike other crossings, such as Manzhouli-Zabaykalsk, which has extensive bogie exchange and transshipment yards, the Tongjiang-Nizhneleninskoye bridge appears to be designed to minimize these requirements.Ibid[46] It appears that the largely dual gauge tracks allow for rail freight to be directly transferred or continue operation without the need for bogie exchanges, depending on locomotive compatibility.Ibid[47] According to Rail Journal, the “bridge can carry trains operating on Russia’s 1520mm-gauge and China’s 1435mm-gauge tracks, with Russian-gauge trains able to travel 15km to a depot in China.”https://www.railjournal.com/infrastructure/first-china-russia-cross-border-rail-bridge-completed/[48]

Conclusion

The long-term trajectory of Chinese-Russian trade will likely depend on how both countries address infrastructure concerns and expand border trade capacity amid shifting geopolitical and economic pressures. First, international geopolitical and economic situations influencing Chinese-Russian trade remain extremely fluid. While Russia has largely turned to eastern markets for the export of natural resources, including timber and energy products, growing demand from Asian countries, particularly China, has so far outpaced what Russia can supply. Russian officials have consistently stated radical reforms to Russia’s Eastern Polygon trade infrastructure must be made to properly accommodate growing demand in the east while coping with a lack of trade cooperation from the west. While recent and ongoing projects have made notable improvements to border infrastructure and trade facilitation between the two countries, few significant impacts are expected in the near term of twelve to twenty-four months. Conversely, the most significant impacts are expected from current, future, and proposed initiatives aimed at addressing visible border bottlenecks and expanding trade capacity through the end of the decade.

To fully assess the long-term implications of border crossing infrastructure development between China and Russia, sustained monitoring of major checkpoints will be essential. Future research should prioritize imagery and open-source coverage of construction progress, changes in freight volume, and road and rail network upgrades on both sides of the border. Additionally, tracking new trade agreements, changes in customs procedures, and economic developments near border areas can provide insights into how both Russian and Chinese infrastructure investments translate into trade flows.

Limited transparency from both Chinese and Russian government and media sources significantly hinder assessments of border infrastructure development and trade trends, especially regarding project intent and pandemic-related disruptions. First, there is a lack of open-source information on Chinese and Russian public activities, given the nature of their governance as authoritarian states. Both China and Russia do not publicize most of their infrastructure project information regarding financial data or the exact nature of their public works projects. For example, local planning documents would help clarify the nature of what exactly both countries are constructed, and would reduce uncertainty in assessing whether buildings have border control, tourist, manufacturing, or other functions.

Second, the same lack of publication applies to data on COVID-19 and its effects on passenger and cargo travel between China and Russia. This information would provide more insight on past activities between the countries, such as tourist or visitor statistics, as well as shifts in trade actions; such as if medical products were traded more than raw materials from 2020 to 2021. Such information could explain why certain changes in construction cycles appeared (or did not) through fluctuations in the amounts of lumber, metals, and other material transported.

This analysis could be improved by a more thorough pre-2020 baseline, and more building-level identification. Though this is out of the project’s scope, a greater amount of background information would help contextualize the reasoning behind some of the changes along the border, as well as why construction cycle or traffic fluctuations occurred. Additionally, in collecting and analyzing imagery, taking the time to identify certain buildings near the border itself would help provide context for changes.

Things to Watch

Attributes that might be relevant to future researchers include lane expansions, bridge construction, increased border security infrastructure, increased traffic volumes in both commercial and passenger vehicles, and a greater presence of raw materials around the border. Other relevant information to watch includes the following:

- Mohe – Dzhalinda crossing: As previously stated, the planned establishment of a crossing between Mohe, China and Dzhalinda, could significantly expand the ability for both countries to move cargo and travelers across the border. This would also increase the amount of revenue for both countries. However, the extent of this is unclear, as analysis indicates that China benefits more than Russia, from an economic standpoint.

- Certain Russian cities close to the border provide additional land transport access, primarily in rail-based infrastructure, to the primary border crossing locations, including the:

- Continuation of upgrades at the Skovorodino railyards, 42.5 miles north of Dzhalinda, potentially contributing to economic activity at the planned Mohe-Dzhalinda crossing.https://russiaspivottoasia.com/yakutia-to-revive-skovorodino-railway-with-connections-through-to-north-china/[49]

- Rail station upgrades at Birobidzhan, the administrative center of Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast, located 79 miles north of Nizhneleninskoye –monitoring this hub could reveal the economic impact of the border crossing.https://infobrics.org/post/33318[50]dvnovosti.ru[51]

- Continued development at Borzya, roughly 68 miles northwest of the Manzhouli-Zabaykalsk crossing, in connecting the TSM to the border crossing.railway.supply[52]

- Rail station expansion to increase cargo and passenger capacity in Ussuriysk, 40 miles east of the Dongning-Poltavka crossing. Ussuriysk is key to increasing grain shipments through Siberia and into China.rzd-partners.ru[53]

References

- https://www.cfr.org/article/where-china-russia-partnership-headed-seven-charts-and-maps

- https://www.caop.org.cn/

- http://gudok.ru

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- http://ng.ru

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- https://worldview.stratfor.com/situation-report/russia-government-approves-expansion-bam-trans-siberian-railway

- Ibid

- gudok.ru

- Ibid

- Ibid

- https://www.railwaygazette.com/policy/russian-and-chinese-railways-plan-strategic-co-operation/66601.article

- Ibid

- Ibid

- https://russiaspivottoasia.com/development-of-the-zabaikalsk-manzhouli-russia-china-border-checkpoint/

- https://www.newsilkroaddiscovery.com/russia-china-speed-up-construction-of-second-railway-line-at-zabaikalsk-manchuria-crossing/

- https://russiaspivottoasia.com/development-of-the-zabaikalsk-manzhouli-russia-china-border-checkpoint/

- https://russiaspivottoasia.com/new-russian-rail-digital-container-terminal-to-china-being-constructed/

- http://delo-group.com/

- prim.rbc.ru

- Ibid

- dzen.ru

- Ibid

- https://www.globalconstructionreview.com/china-and-russia-agree-to-build-second-rail-bridge-over-the-river-amur/

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- https://www.eurasiareview.com/10032023-since-russia-cant-afford-it-china-will-build-railway-north-to-sakha-analysis/

- https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/14/asia/china-russia-blagoveshchensk-heihe-highway-bridge-mic-intl-hnk/index.html

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- https://www.iea.org/countries/china/coal

- https://www.openrailwaymap.org

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- https://www.railjournal.com/infrastructure/first-china-russia-cross-border-rail-bridge-completed/

- https://russiaspivottoasia.com/yakutia-to-revive-skovorodino-railway-with-connections-through-to-north-china/

- https://infobrics.org/post/33318

- dvnovosti.ru

- railway.supply

- rzd-partners.ru

Look Ahead

The authors believe it is likely border crossing development will continue, despite ongoing economic concerns related to tariffs and the Russo-Ukrainian conflict. As China and Russia solidify strategic and economic ties in an uncertain global balance of power, border development represents cooperation in the Sino-Russian relationship. China's proportionally higher number of construction instances indicates that its economy is faring better, as compared to the slower pace of Russian construction, likely due to the latter's wartime economy shifting away from civil investment. Thus, Chinese-side projects will likely continue to outnumber those on the Russian side as China seeks to increase its economic capacity via transport infrastructure.

Things to Watch

- How will infrastructure improvements provide additional land transport access (primarily in rail-based infrastructure) to the primary border crossing locations?

About The Authors

Mercyhurst University Faculty

Mercyhurst Graduate Student

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Contributor

Mercyhurst Student Author

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.