Overview

Since 2017, the PLA has aggressively expanded its heliport network along the Sino-Indian border. The PLA's expansion is curious considering that many of its newest heliports are located at extreme elevations that may degrade its current vertical lift capability.

Findings suggest that this expansion may be an overzealous force projection mechanism underpinned by a slow-developing domestic rotorcraft capability. Furthermore, this expansion may also be the manifestation of the PLA's modernization efforts both technologically and doctrinally.

Activity

This GEOINT analysis uses imagery and GIS to assess the PLA's helicopter force changes in relation to its high-altitude heliport expansion along the Sino-Indian border.

Introduction

Introduction

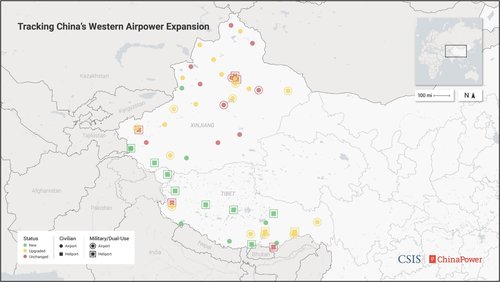

The Sino-Indian border dispute has a contentious and militant history spanning more than sixty years. Multiple conflicts, often deadly, have pockmarked areas along the border, further entrenching each country’s position and diminishing any perceived chance at resolution. Two recent conflicts in 2017 and 2020 likely drove the PLA to invest heavily in military infrastructure in the region – particularly aviation infrastructure.1 The sheer number of new or upgraded airports/heliports near the Sino-Indian border is astounding. Between 2017 and 2021 the PLA broke ground on fifteen new airports/heliports along the Indian border with another twenty-two upgraded in Tibet and Xinjiang.2 While the PLA’s airport expansion seems appropriately tailored to its fixed-wing capabilities, its heliport expansion is more puzzling. Tibet and Xinjiang host some of the highest elevations in the world that are coupled with mountainous terrain and harsh environmental conditions. This combination makes helicopter flight exceptionally difficult. If PLA rotorcraft can operate near the border without operational degradation, this will be a testament to its growing vertical lift capability. If the PLA cannot effectively operate in the region, its heliport expansion is likely wasting resources. This geospatial intelligence assessment examines Chinese high-altitude heliports near the Sino-Indian border to evaluate the PLA’s vertical lift capability in the region and how the PLA might leverage these facilities in the future.

Key Judgements

- The PLA high-altitude heliports probably serve as tactical logistics hubs as evidence by their placement in an interconnected network of valleys.

- High-altitude heliport construction is probably behind schedule.

- The PLA will may leverage heliports as a dual-use Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) infrastructure.

- The PLA will probably continue to rely on Russian helicopters to fill capability gaps.

Key Assumptions

- (Primary) Little evidence suggests that PLA helicopters are currently suited for sustained high-altitude combat flight operations; however, helicopter performance is also difficult to determine without authoritative performance data. As such, it is assumed that PLA helicopters are probably not capable of full-spectrum operations in high-altitude environments – especially along portions of the Sino-Indian border.

- For the purposes of this assessment, “high-altitude” is defined as an elevation at or above 14,500 feet mean sea level (MSL). While the elevation figure is arbitrary, it does represent a benchmark at which military rotorcraft operations become exceedingly difficult.

- For the purposes of this assessment, “full-spectrum helicopter operations” is defined as the ability to perform all missions intended by the PLA. The inability to perform “full-spectrum helicopter operations” may be the complete lack of a certain capability (i.e. attack aircraft cannot fly in the region) or a degradation of a capability (i.e. an aircraft can only transport two soldiers instead of eight).

Analytical Gaps and Limitations

- This assessment does not evaluate the current or proposed PLA order of battle. While examining the order of battle likely holds additional insights, this is beyond the scope of this assessment.

- This assessment only evaluates helicopter activity at heliports. It does not evaluate airports, including those with helicopter infrastructure. As of June 2023, no Chinese airports were located above 14,500 feet MSL.

- Reporting from Chinese sources is likely state-affiliated or portrays state-sanctioned information. As such, the validity of Chinese information may be inaccurate and often overstated.

Framing the Discussion

Framing the Discussion

After Mao Zedong’s establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, China rejected previously agreed-upon borders with neighboring countries including India.3 This rejection caused a militant border dispute between India and China that remains tense to this day. Figure 1 shows the disputed border and territories. The disputed portions of the border, known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), is one of the primary factors contributing to ongoing regional disputes.4

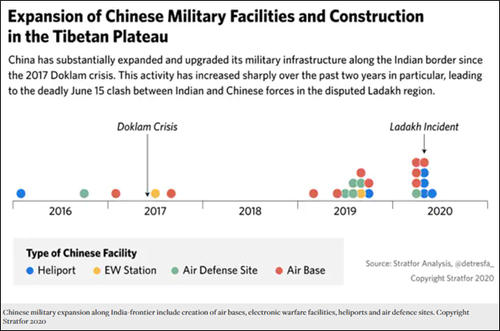

Two border clashes in 2017 and 2020 appear to have catalyzed the PLA’s infrastructure expansion in the region. Both the Doklam conflict (2017) and the Ladakh conflict (2020) turned deadly, prompting outrage from both countries and military buildup. Prior to 2017, the PLA operated only five heliports along the border. The current heliport expansion grows that number to thirteen. According to the CSIS China Power Project, most new heliports and/or heliport upgrades started construction in approximately 2020.

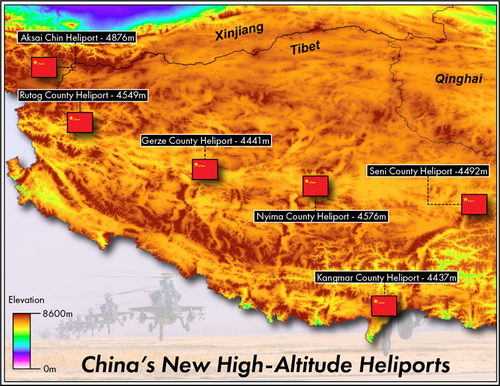

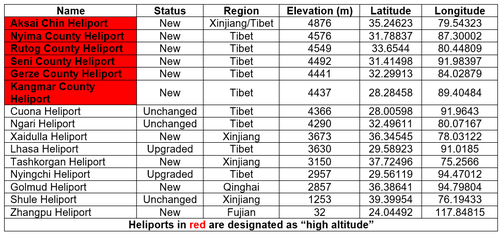

Six of the eight new heliports within the area of interest are located at or above 14,500 feet MSL. Figure 4 shows the regional dispersion of these six heliports.

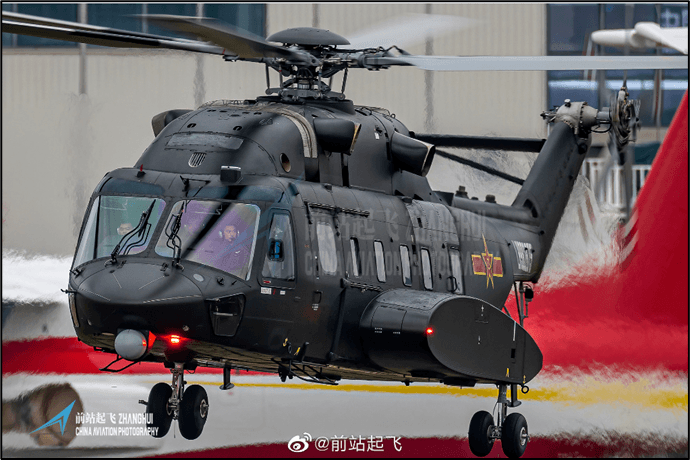

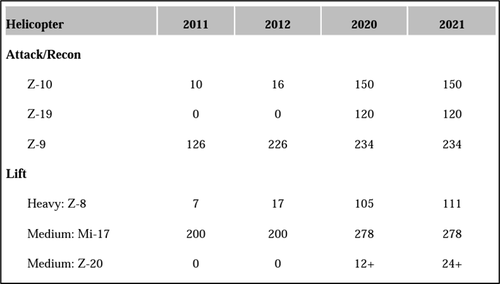

The PLA’s helicopter fleet comprises utility, heavy lift, and attack platforms.5 Over the last decade, the PLA increased the quantity and type of its helicopter inventory.6 Historically, the PLA relied on foreign-built platforms such as the Russian Mi-17. However, in recent years the PLA has made a concerted effort to increase its force with domestic solutions. Figure 5 shows the PLA's helicopter inventory breakdown from 2011 to 2021.

Four PLA helicopters stand out as possible candidates for high-altitude operations across China’s western border: the Mi-17, Z-8, Z-10, and Z-20 (Figures 6-9). These aircraft operate in the region and likely have the capability to do so with some degree of effectiveness. Furthermore, multiple Chinese media outlets such as Central China Television have touted that these four airframes are ready for high-altitude operations.

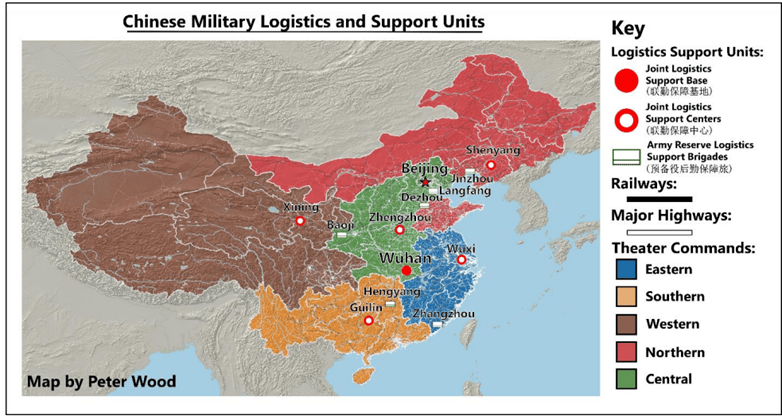

The heliport expansion is also being conducted against the backdrop of military modernization. In 2013, China's Central Military Commission (CMC) began a series of military reforms to modernize capabilities, organizational structure, and doctrine.7,8 Some examples of this modernization include the establishment of theater commands, the Joint Logistic Supply Force (JLSF), and the integration of novel technologies such as autonomous and unmanned systems (Figures 10-12). Considering the long-term and strategic nature of the CMC's modernization efforts, it is possible that the PLA's heliports are designed and implemented to account for changes in doctrine and technology. The potential gaps in operational helicopter capability may be opportunities for the PLA to flaunt its perceived advancements.

Analytic Methodology

Fifteen heliports were designated for satellite imagery analysis (Table 1). Six primary targets (heliports at or above 14,500 feet MSL (4,420 meters)) and nine secondary targets (other heliports) were selected. The secondary targets offered key insights for comparative analysis. Fourteen of the heliports are in western China. One recently constructed heliport, located in southeastern China, was included for additional comparative analysis. A geographic information system (GIS) was used to assess two factors: regional elevation and heliport placement. Analysis of the proximate elevation was conducted to ascertain what elevations PLA rotorcraft are expected to operate at. The heliport placement analysis was designed to determine any key terrain, unique geography, or other relevant factors about the heliports’ placement that might give insight into the PLA’s intentions.

Key Judgements

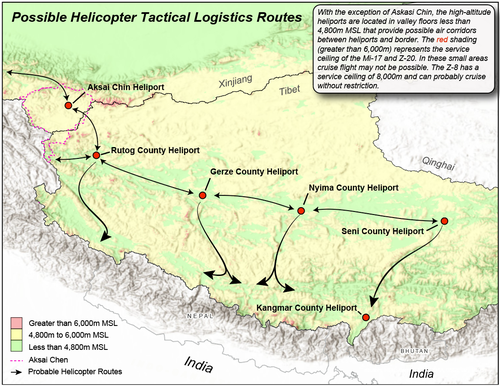

The PLA high-altitude heliports probably serve as tactical logistics hubs as evidenced by their placement in an interconnected network of valleys.

All high-altitude heliports are located at intersections of valley systems that connect the heliports to one another and to the western border. The valley system likely provides three advantages necessary for operations. First, the valley system takes advantage of lower elevations which helps preserve already limited helicopter performance. Second, the valley system probably provides a safer and more predictable route structure during poor weather navigation. Janes indicates that PLA helicopters may be equipped with terrain-following radar.9 This may be the primary means of navigation in the absence of reliable instrument navigation infrastructure. Third, the valley system may provide protection from enemy weapon systems that may seek to detect, track, or destroy PLA aircraft. In a region where the transportation infrastructure is dominated by roads of varying conditions, the heliports may provide the PLA with a much more timely and tactical logistics solution.

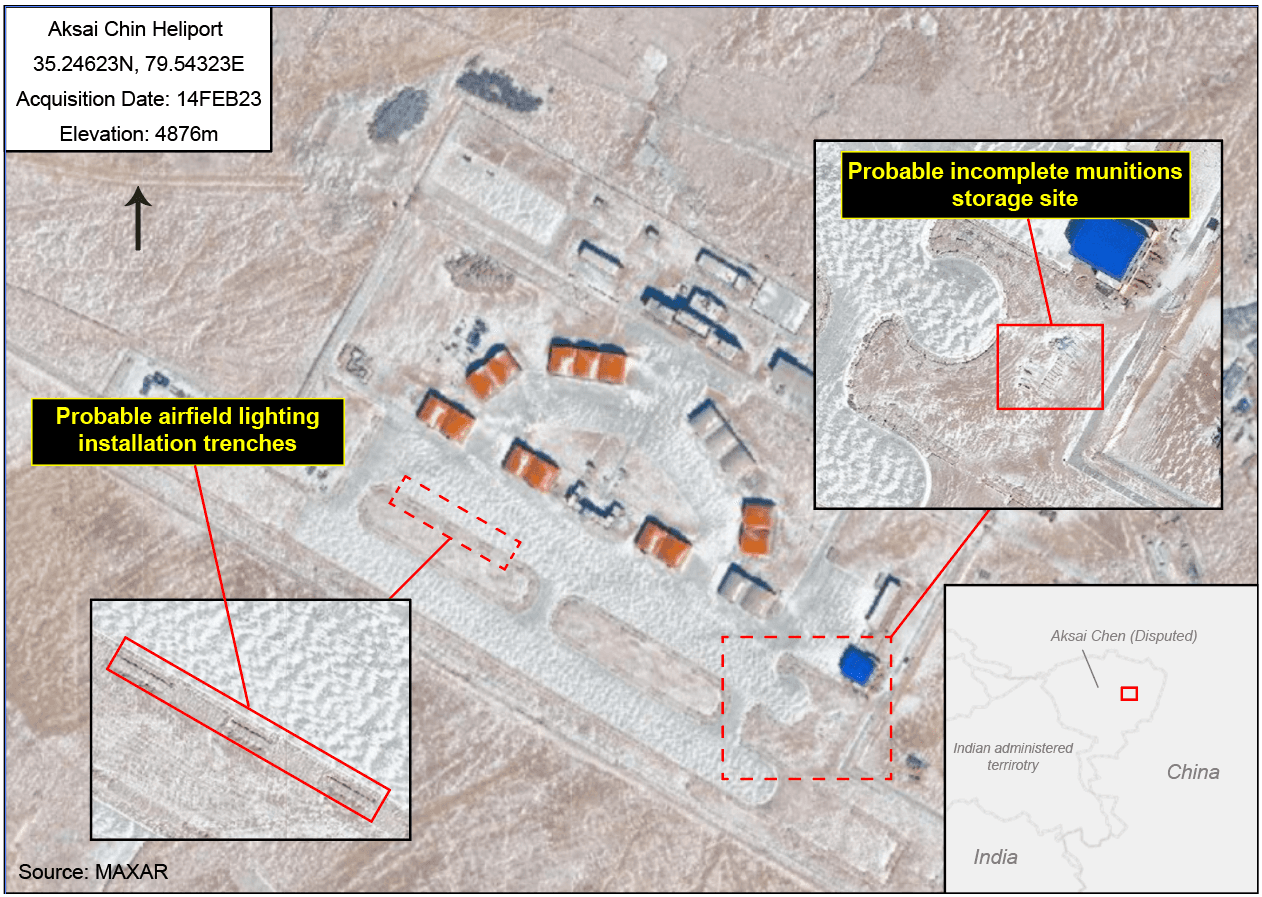

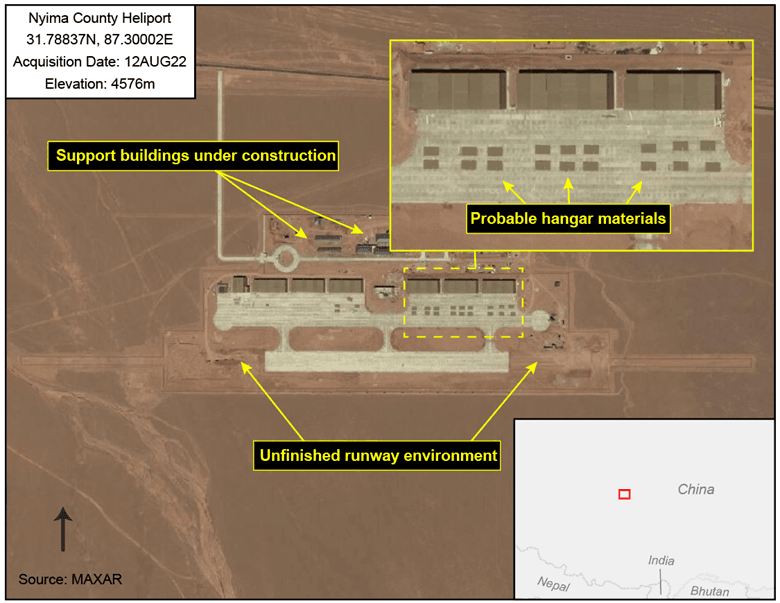

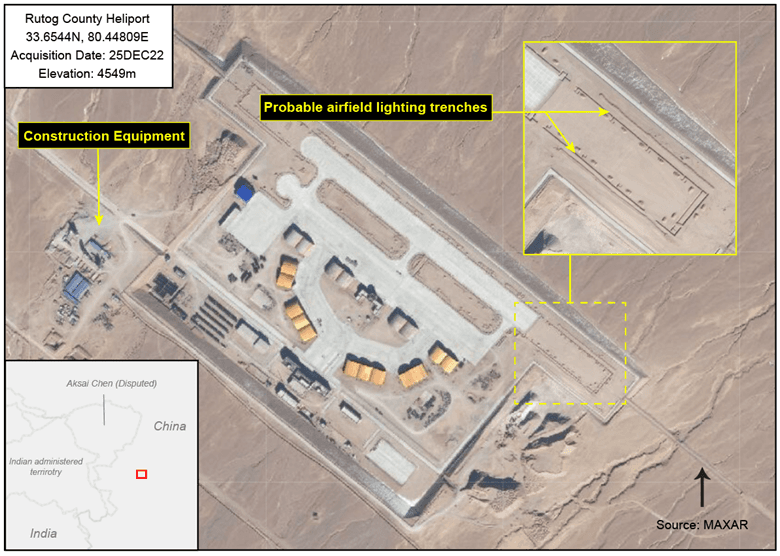

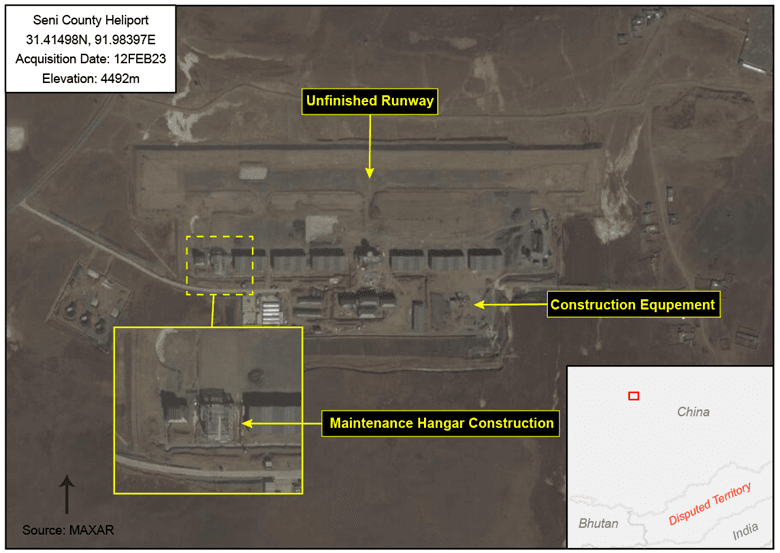

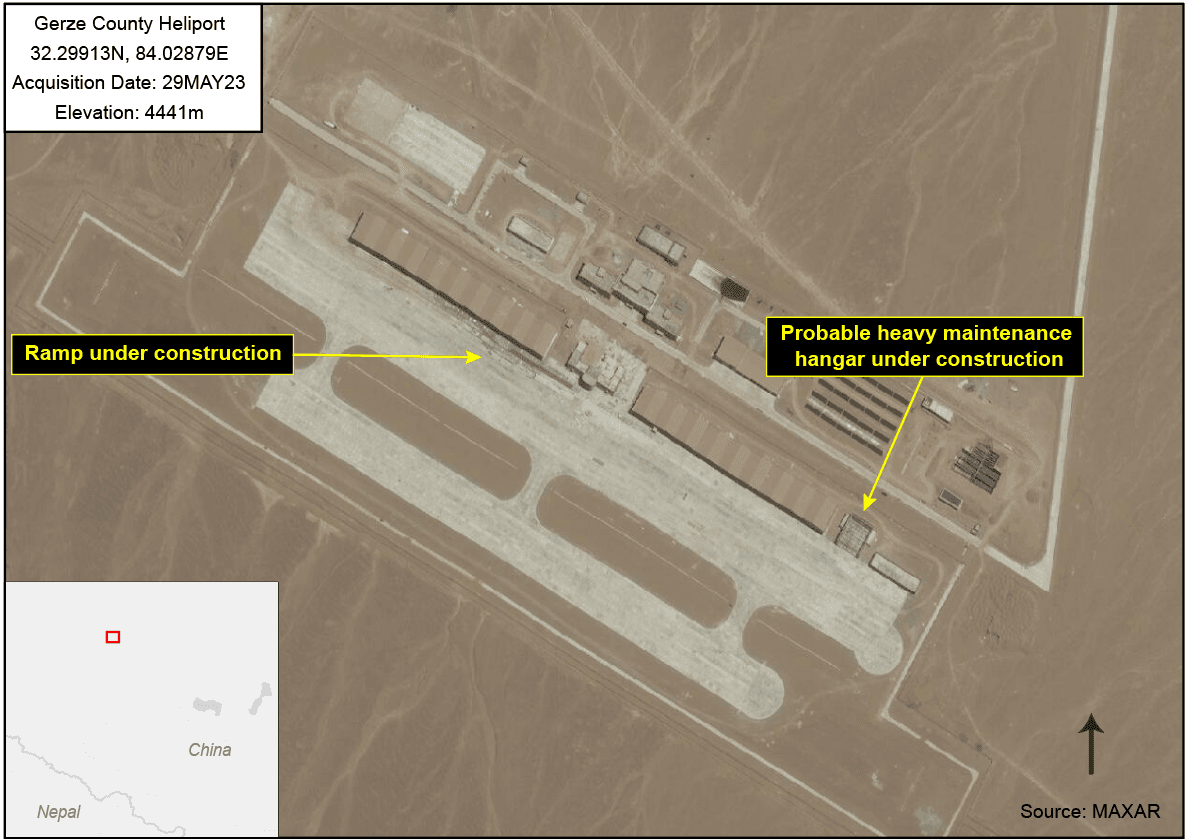

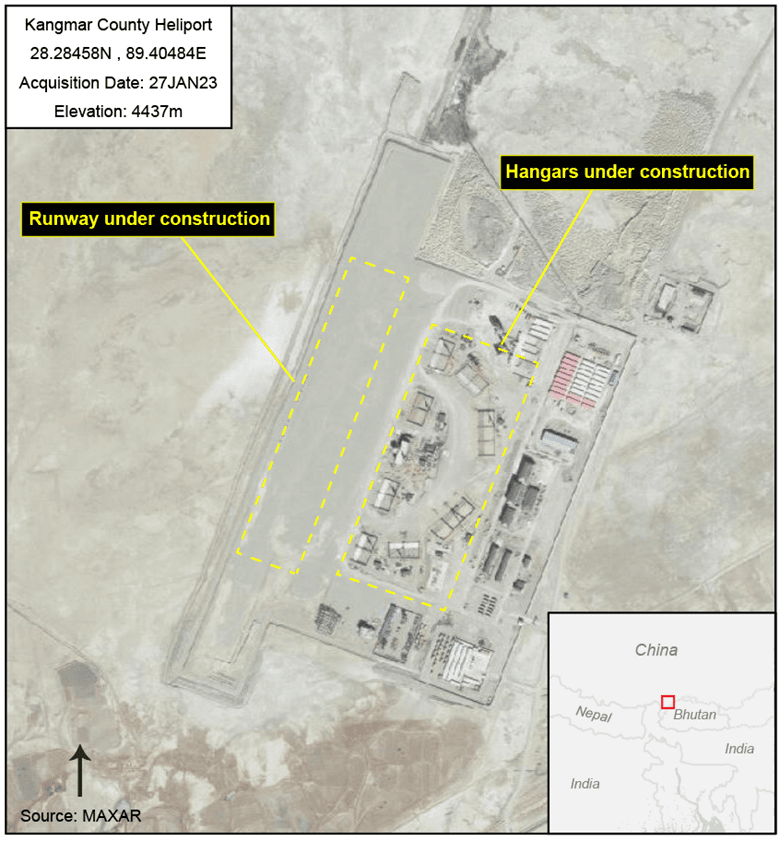

High-altitude heliport construction is probably behind schedule.

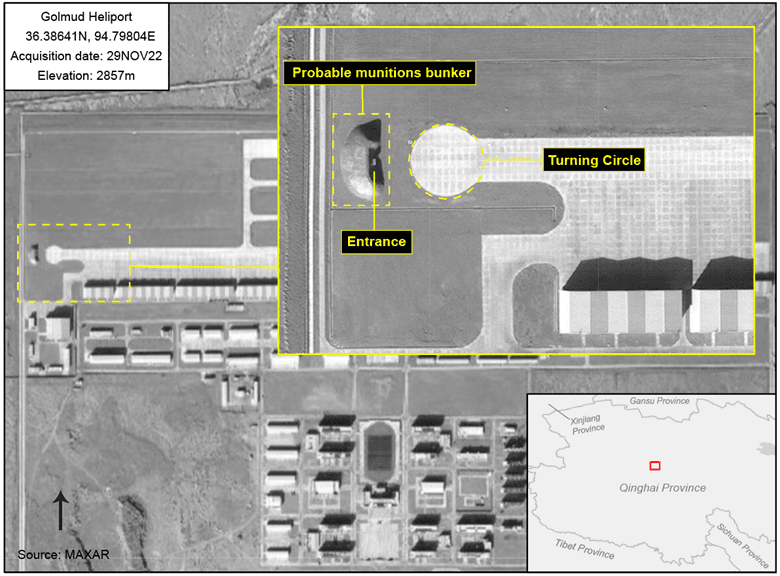

Imagery analysis suggests that heliports constructed at lower altitudes took approximately 18 to 24 months to complete. Conversely, despite start dates in approximately 2020, all heliports above 14,500 feet MSL remain under construction. Figures 14-19 contain imagery depicting signs of this construction. Some signs of construction are more blatant than others. For example, some heliports still lack a runway (Figures 18 and 19) and/or show incomplete hangars (Figures 16,18, and 19). Other indications are more nuanced such as the presence of airfield lighting trenches (Figure 14 and 17). Many operational airfields and heliports contain what are probably munitions bunkers (Figure 15). This may serve as another progress marker for those new heliports lacking this feature (Figure 14). Considering the challenging logistics needed to construct heliports at high-altitude, it is probable that the delays are logistics-related.

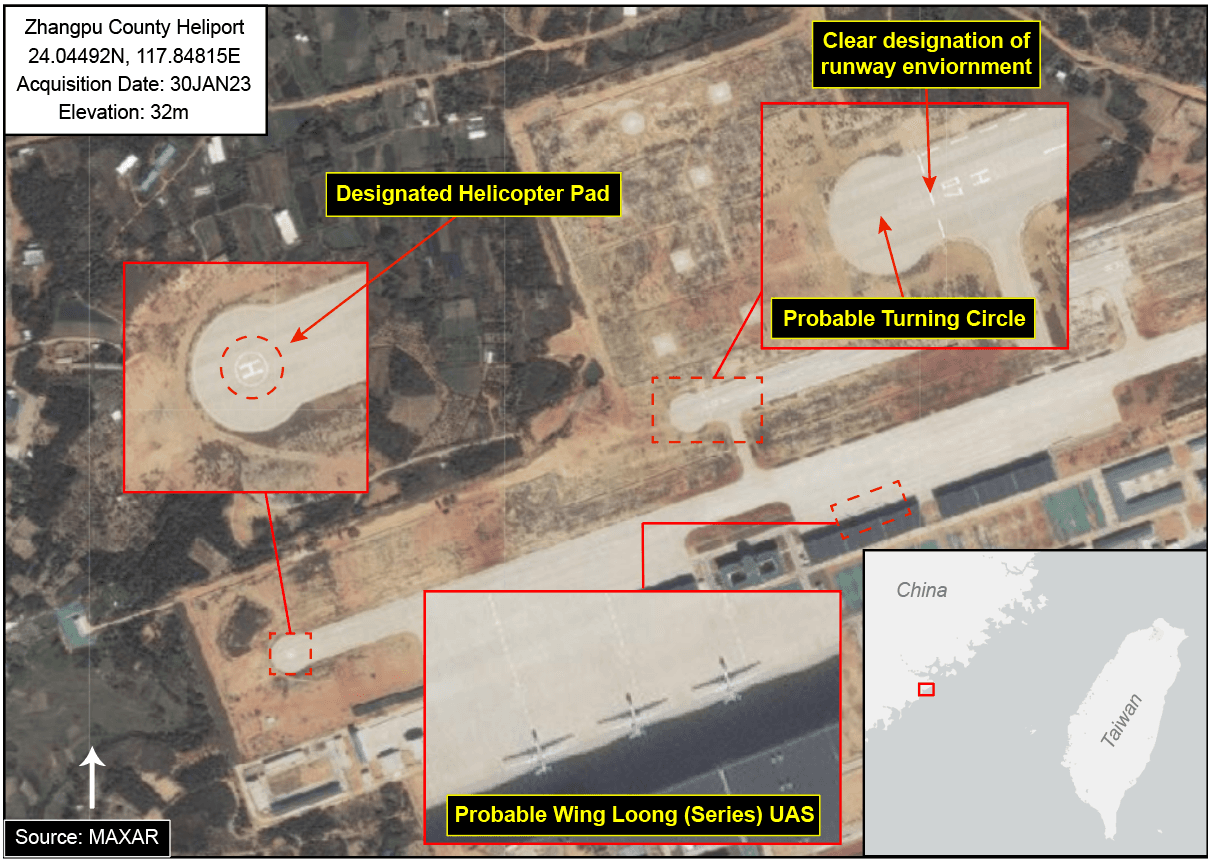

The PLA may leverage heliports as a dual-use UAS infrastructure.

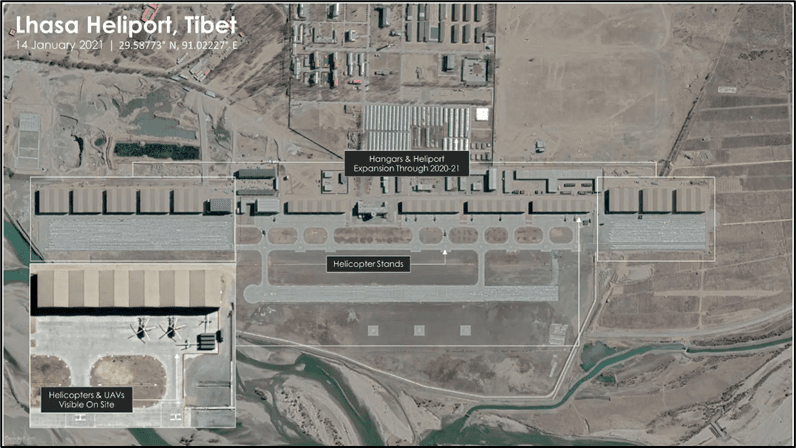

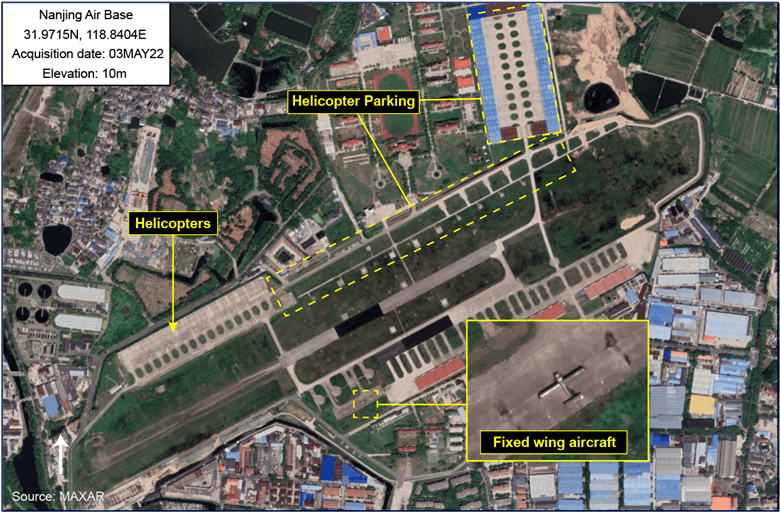

Imagery and open-source reporting revealed that UAS likely operate from heliports across China. In 2021, The Drive first reported the presence of UAS at the Lhasa heliport in Tibet (Figure 21).10 Imagery analysis also revealed the presence of UAS at the newly constructed heliport in Fujian (Figure 22). While not located in China's Western Theater, it is one example of a newly constructed heliport with this type of activity. No UAS were detected in the satellite imagery review of the remaining thirteen heliports; however, fixed wing aircraft were observed on helicopter bases in China – further supporting a precedent for dual-use fixed wing activity at heliports (Figure 23).

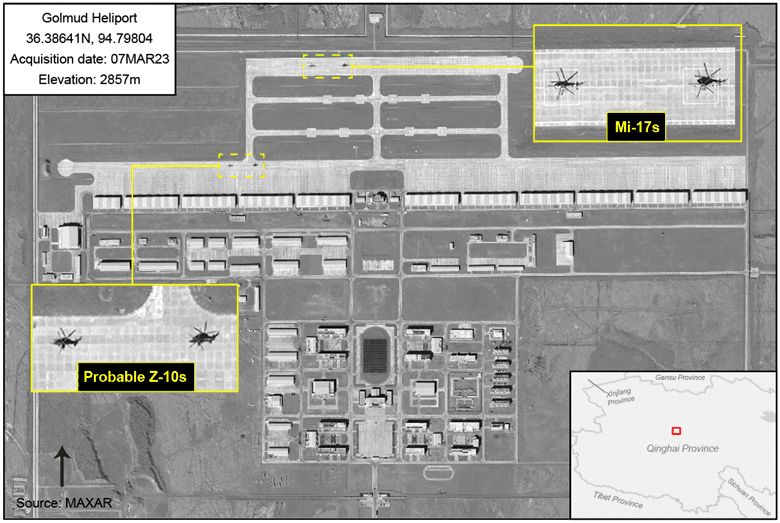

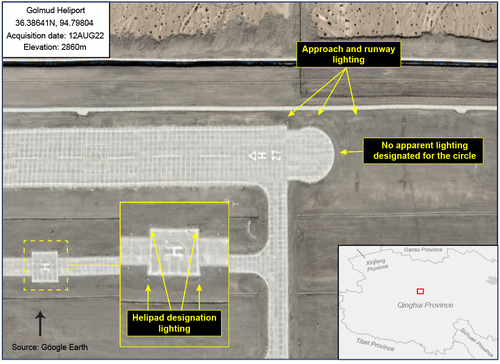

The presence of turning circles on newer heliports may be a feature designed for fixed wing aircraft, particularly UAS, on short runways. A turning circle on the runway likely has little utility for helicopters; however, this feature would allow a fixed wing platform to maximize the entire length of the runway for takeoff and landing - a critical requirement at high altitude. The turning circles do give the appearance of a possible helicopter landing point: the circles are not marked as a helipad and lack designated lighting that marks the area as a landing point. Figure 24 shows an example of the turning circle at Goldmud. The square helipad is marked with the traditional "H" and has designated lighting that marks the helipad boundaries, but Golmud's turning circle is not marked as a helipad and lacks lighting along its circumference.

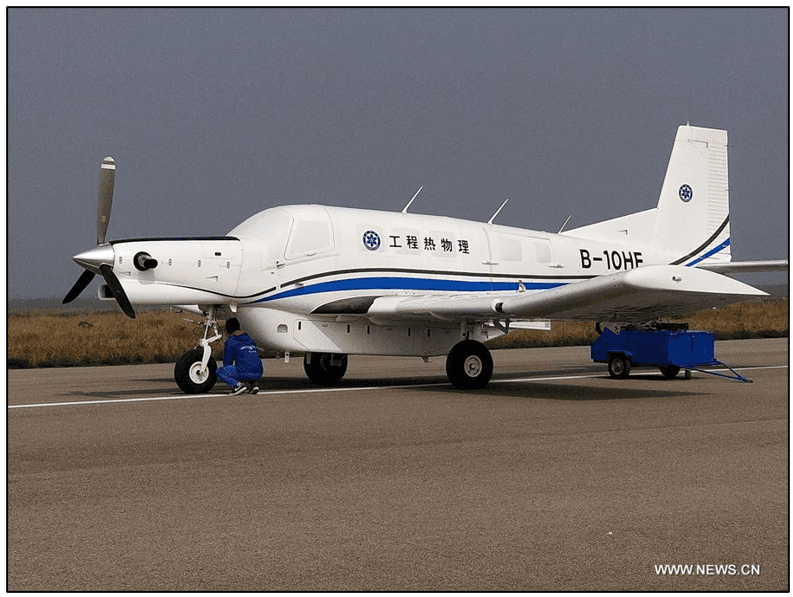

The average length of the high-altitude heliport runways is approximately 600 meters. At high altitude, this length may be insufficient for many fixed wing UAS in the PLA's inventory; however, it may be ideally suited for short takeoff and landing (STOL) UAS. Various Chinese media outlets, including the Global Times, purports that the PLA and JLSF are evaluating a variety of STOL UAS designed for cargo and can operate from short runways and in the high-altitude environment of western China.11,12 One example is the AT200 (Figure 25), a modified version of Pacific Aerospace's (NZL) P750XTOL (Figure 26). This aircraft is able to operate to and from runways measuring less than 200 meters.13 Considering the resource-hungry nature of helicopter operations and high-altitude logistics, STOL cargo aircraft may be ideally suited for expeditiously resupplying these strategic nodes or the elements the helicopter force supports.

The PLA will probably continue to rely on Russian helicopters to fill capability gaps.

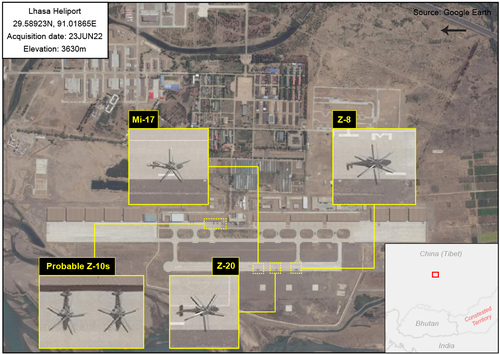

A comparative analysis of operational heliports in the region revealed an overwhelming presence of Mi-17s. While Chinese Central Television suggests that other airframes have been operating in the WTC, imagery collection over the past two years almost exclusively shows Mi-17s at heliports.14 The only exceptions were the Lhasa and Golmud bases – the two largest heliports in Tibet and Qinghai respectively and located at much lower altitude. At both heliports, the Mi-17, Z-8, Z-10 (probable), and Z-20 were identified (Figure 27 and 28).

The Mi-17 outnumbers the Z-8 at approximately 2:1 and the Z-20 more than 20:1.15 It is possible that the large presence of Mi-17s in the region says more about airframe availability than capability. As operations continue and more heliports are operationalized, it will be important to monitor whether Z-8, Z-10, and Z-20 activity expands. Regardless, the PLA’s reliance on the Mi-17 remains.

Furthermore, in 2020 The Drive reported that the PLA may be investing in newer versions of the Mi-17 that likely provide better high-altitude performance.16 If the PLA is investing in new Mi-17 helicopters for performance, this is further evidence that the PLA’s domestic solutions are not yet comparable to Mi-17 and/or the domestic production rate is lagging.

Satellite imagery analysis also revealed Mi-17s configured with probable weapons pylons. If this configuration continues to be observed in place of dedicated attack aircraft, it could indicate that the Russian platform is more capable at high altitudes than its domestic attack solution. Figure 29 shows the satellite imagery of an Mi-17 with and without the weapons pylons (top). Examples of what the configuration probably looks like is shown below each satellite image.

Lastly, Reuters indicates the Chinese and Russians are collaborating on the AC332 AHL, a joint-heavy lift helicopter destined for the Western Theater. The AC332 AHL is predicted to be the PLA's highest performing heavy lift helicopter. The helicopter will be designed to carry 600kg loads at 4500 meters.17 Model rendering resembles an enhanced Z-8 or a loose attempt at mimicking the United State's CH-53's heavy lift design. The AC332 AHL collaboration agreement between China and Russia was signed in 2016 and still appears to be in the design phase.18 If the AC332 provides a capable and affordable heavy-lift solution, it could be a viable high-altitude platform that exceeds the capability of its current force.

So What?

The PLA's use of its high-altitude heliport network as force projection mechanism is probably over-zealous.

The apparent and significant delays in high-altitude heliport construction is one probable indication of the challenges related to high altitude. Furthermore, the lack of operational sites leaves the larger force still untested. When combined with the PLA's historically sparce presence in the region, the force projection it aims to display may be established on a rocky foundation.

The PLA's domestic rotorcraft program is probably not mature enough to handle large-scale operations at high altitude.

The PLA, whether by intent or fortuity, appears continuously reliant on Russian aircraft. The sheer number of Mi-17s in the PLA's inventory (particularly along the Sino-Indian border), continued investment in new Mi-17 airframes, and evidence of future Sino-Russian collaborative rotorcraft programs give substance to this assertion. The PLA, at least in public forums, have immense pride in their ability to provide a domestic rotorcraft capability; however, little evidence suggests that this capability is prepared for the challenges of sustained full-spectrum and large-scale operations at high altitude at this time.

The PLA's high-altitude heliport network is probably a manifestation, both technologically and doctrinally, of its military modernization efforts.

As the CMC continues its modernization efforts, it is possible that the heliport network is designed to facilitate tactical, operational, and/or strategic goals that are in alignment with its new doctrinal tenets. If true, the PLA's vertical lift capability may fulfill different objectives at high altitude (i.e. strategic logistics) compared to legacy capabilities at lower altitude (i.e. air assault). This notion is further reinforced by evidence of the PLA integrating novel technologies such as unmanned aircraft into its fold. Whether these technologies are integrated as a part of modernization efforts, filling capabilities gaps, or both, the developing heliport network may be an example of its modernization methodology at work.

Why China's High-Altitude Heliports are Ambitious

Given the sustained tension between India and China, the PLA's desire for an expanded helicopter infrastructure is not surprising. This desire is probably reinforced by a historically lackluster disaster response capability in the region. Previously, vast expanses of Tibet and Xinjiang were void of a helicopter capability that will now be more readily filled. If executed well, the improved network could provide a quicker military response to conflicts or disasters and improve military logistics along the border.

The predominant factor that likely complicates this project and future regional sustainment is the extreme altitude itself. War on the Rocks suggests that the Sino-Indian border altitudes are extreme enough to cause acclimation issues, degrade logistical capabilities (i.e. poor diesel engine performance), and alter combat norms (i.e. ballistics) that may negatively impact fundamental soldiering.19 When combined with regional environmental considerations such as extreme temperatures and mountainous terrain, the matter is complicated further.

Helicopters are also not immune from these challenges and are uniquely vulnerable to the negative effects of high altitude. Simply stated, the higher in altitude a helicopter operates the less capable its rotor blades are producing lift and the less power its engines can generate. The helicopter is also prized for its ability to hover. It is the helicopter's ability to hover that provides much of its military advantage. Hoisting operations, equipment sling loads, and troop fast rope insertions are three examples of helicopter capability predicated on its ability to hover. Hovering flight, specifically high hovering flight, is extremely power intensive. As such, it is one of the first capabilities lost at high altitude, or requires drastic modifications to helicopter loading (less fuel, armament, and/or cargo) to maintain. Lastly, high altitude negatively impacts a helicopter's ability to dynamically maneuver. Maneuverability is of marginal importance during peace-time operations but is critical during combat.

The summation of these factors presents a formidable challenge for the PLA. First, the PLA will likely grapple with the logistical challenge of heliport construction and sustainment at extreme elevations. Second, the PLA will almost certainly experience a degradation in helicopter performance, though to what extent is unknown. Both of these considerations stand to negatively impact China's combat effectiveness in the region without deliberate mitigation strategies.

Contributor Note

The author is an active duty H60 instructor pilot with over fourteen years of service between the United States Army and the United States Coast Guard. The report is a product of the author's student role but draws upon aggregate past experience and does not represent an official position of past employers.

References

1 Rossow, Richard M., Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., and Kriti Upadhyaya. “A Frozen Line in the Himalayas.” CSIS. Accessed April 14, 2023. https://www.csis.org/analysis/frozen-line-himalayas.

2 “How Is China Expanding Its Infrastructure to Project Power along Its Western Borders?” ChinaPower Project, March 23, 2022. https://chinapower.csis.org/china-tibet-xinjiang-border-india-military-airport-heliport/.

3 Rossow, Richard M., Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., and Kriti Upadhyaya. “A Frozen Line in the Himalayas.” CSIS. Accessed April 14, 2023. https://www.csis.org/analysis/frozen-line-himalayas.

4 Krishnan, Ananth. “Line of Actual Control: India-China: The Line of Actual Contest.” The Hindu, June 14, 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/line-of-actual-control-india-china-the-line-of-actual-contest/article31822311.ece.

5 Fox, Tom. “China Maritime Report No. 17: The PLA Army's New Helicopters: China Maritime Report No. 17: The PLA Army's New Helicopters: An ‘Easy Button’ for Crossing the Taiwan Strait? An ‘Easy Button’ for Crossing the Taiwan Strait?” Site. U.S. Naval War College - China Maritime Studies Institute. , December 2021. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/.

6 Ibid

7 Allen, Kenneth, Dennis J Blasko, and John F Corbett. “The PLA's New Organizational Structure: What Is Known, Unknown and Speculation (Part 1).” The Jamestown Foundation. China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 3, February 4, 2016. https://jamestown.org/program/the-plas-new-organizational-structure-what-is-known-unknown-and-speculation-part-1/#.VrwLCfmLSUl.

8 Finkelstein, David M. “The PLA’s New Joint Doctrine.” Center for Naval Analyses, September 2021. https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/the-plas-new-joint-doctrine.pdf

9 London, Andrew. "China unveils ASW version of Z-18 helicopter". IHS Janes 360. August 20, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140822111143/http://www.janes.com/article/42184/china-unveils-asw-version-of-z-18-helicopter

10 Detresfa_. "China Is Building A Massive Helicopter Base On The Tibetan Plateau". The Drive, November 17, 2021.https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/43130/china-is-building-a-gargantuan-heliport-on-the-tibetan-plateau

11 Rupprecht, Andreas. "Three-engined variant of China's Tengden TB001 UAV makes maiden flight". Janes, January 21, 2020. https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/three-engined-variant-of-chinas-tengden-tb001-uav-makes-maiden-flight

12 Helfrich, Emma. "China’s Four-Engine ‘Scorpion D’ Cargo Drone Has Flown". The Drive, October 26, 2022. https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/chinas-four-engine-scorpion-d-cargo-drone-has-flown

13 "AT200 Cargo Unmanned Aerial Vehicle". Aerospace Technology. Retrieved June 10, 2023. https://www.aerospace-technology.com/projects/at200-cargo-unmanned-aerial-vehicle/

14 Military Helicopter Videos (CCTV Footage). "Chinese PLA Z-10 and Z-18 helicopters exercise in high-altitude". YouTube, July 31, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdU5H52Jn6s

15 Fox, Tom. “China Maritime Report No. 17: The PLA Army's New Helicopters: China Maritime Report No. 17: The PLA Army's New Helicopters: An ‘Easy Button’ for Crossing the Taiwan Strait? An ‘Easy Button’ for Crossing the Taiwan Strait?” Site. U.S. Naval War College - China Maritime Studies Institute. , December 2021. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/.

16 "Russia signs contract to develop new heavy helicopter with China". Reuters, November 8, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-signs-contract-develop-new-heavy-helicopter-with-china-2021-11-08/

17 “AVIC Launches Assembly of New Helicopter.” China.org.cn, July 5, 2021. http://www.china.org.cn/business/2021-07/05/content_77606059.htm

18 Ahmedullah, Mohammed. “Chinese Heavy-lift AC332 Helicopter Completes Cockpit Design Evaluation.” Defense Mirror, June 15, 2022. https://www.defensemirror.com/news/32136/Chinese_ Heavy_lift_AC332_Helicopter_Completes_Cockpit_Design_Evaluation#.ZCTnv3bMK3A

19 Millif, Aidan. "Tension high, altitude higher: logistical and physiological constraints on the indo-chinese border". War on the Rocks, June 8, 2020. https://warontherocks.com/2020/06/tension-high-altitude-higher-logistical-and-physiological-constraints-on-the-indo-chinese-border/

Look Ahead

As each high-altitude heliport becomes operational, additional insights may be gleaned into the PLA's intent with its heliport network and any associated vertical lift capability.

Things to Watch

- In what order will the PLA choose to operationalize its high-altitude heliports?

- How does the PLA intend to augment its traditional vertical lift capability with UAS - if at all?

- Will the PLA resource its new high-altitude heliports with domestic rotorcraft?

- What are the implications of the PLA's high-altitude heliport expansion beyond China's borders?

About The Authors

MS Geospatial Intelligence, Johns Hopkins

Methodologies Reviewed by NGA

Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, conclusions, or opinions of the author(s). The published article’s contents, conclusions, and opinions are solely that of the author(s) and are in no way attributable or an endorsement by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the United States Intelligence Community, or the United States Government. For additional information, please see the Tearline Comprehensive Disclaimer at https://www.tearline.mil/disclaimers.