Overview

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is not a monolithic enterprise. Across seven BRI port projects in Central America and the Caribbean, we find evidence that the project partnerships between China and recipient countries vary significantly regarding construction processes and end results.

BRI investment depends on numerous factors, including coordination between the Chinese government and the recipient country's government. When this coordination is undermined by domestic political changes, civil society movements, or international pressure, BRI projects may be cancelled or indefinitely delayed.

Activity

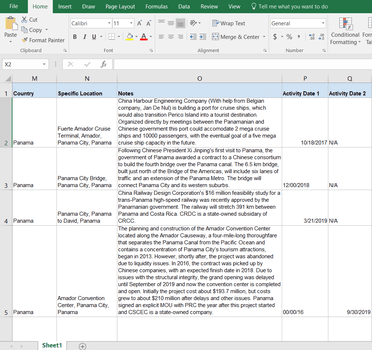

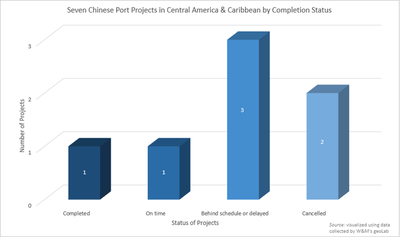

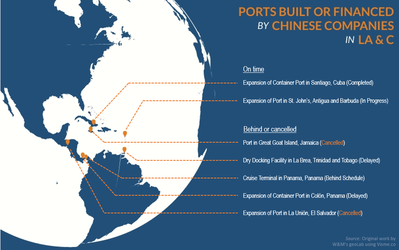

This Tearline article discusses findings from a project which uses open-source data collection and imagery analysis to study the impacts of Chinese development financing in Central America and the Caribbean. The article examines evidence from seven BRI ports across six countries. The port expansion in Santiago, Cuba is completed, but imagery reveals that three of four other ongoing BRI port projects have been delayed and no further construction has occurred in recent months. The remaining two port projects were cancelled.

Introduction

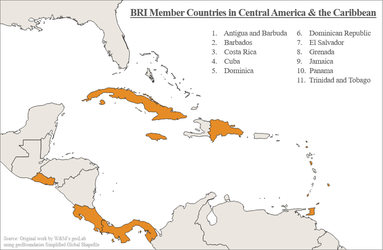

Inaugurated in 2013, China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a series of infrastructure investments and diplomatic endeavors. The BRI seeks to stimulate economic growth through connective infrastructure that better facilitates global trade. It assumes that these activities will have positive spillover effects for nearby sectors and attract more investment. The size of the Initiative is unprecedented, including over 3,485 projects across 138 countries and over 273.6 billion USD in official Chinese financing. After some initial success in Asia and Africa, China expanded the initiative to encompass Central America and the Caribbean (CA & C). Eleven countries in CA & C have signed BRI agreements (see map below). However, the BRI's ability to stimulate economic growth in participating countries is hard to determine and leads to questions of equitability. These projects tend to have greater benefits for China, through positive political externalities, and many projects fail due to delays or cancellations.

In Central America and the Caribbean, waterways are critical to economic development, trade, and transportation. In 2017 alone, ports in this region processed 22.860 million twenty-foot equivalent units of cargo (TEU). Ports are economically and strategically important and, as such, have been at the center of BRI activities in the region. There have so far been seven Chinese-financed port projects in Central America and the Caribbean spanning six countries and including container ports, cruise terminals, and dry docks. The statuses and locations of these ports can be seen in the chart and map below.

Several of these port projects began before the recipient country formally joined the BRI, acting as incentives in the formal negotiation process which is not available on public record. Joining the BRI means that China and the country have signed a memorandum of understanding to support each other's goals, specifically with China investing in large infrastructure projects in the country. Exact start dates of negotiation and construction are unclear, but given the actors involved and increased public/private/government favor towards China, it is clear that these are BRI projects. In this report, each project and its connection to the BRI will be further explained. Of the seven port projects across six countries, one has been completed, four are under construction, and two have been cancelled. The delayed projects have fallen further behind schedule with construction delays in the spring 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like BRI projects in other regions, there has been mixed success with ports in Central America and the Caribbean. Some factors we considered when grading a port project as successful include: (1) if the port followed its planned construction timeline, (2) analysis suggests a high quality of craftsmanship, (3) does not sit unused or under-utilized after completion, and (4) did not receive a negative public response. Conversely, projects that experienced long delays are considered less successful and projects that were cancelled are considered failures.

Lessons to take away from project outcomes:

- Ports are central to most regional economies, so their success/failure correlates to interconnected economic spill-over from related industries.

- The relative success of a port project is dependent on the domestic context of the recipient country and the nature of the relationship between China and the recipient country. For example, the ports in Cuba and Antigua and Barbuda follow their expected construction timelines and benefit from a strong relationship with China. Conversely, the ports in Panama and Jamaica were delayed or cancelled due to domestic political changes and pressures. The port in Trinidad and Tobago has been delayed due to a mismatch of priorities between the two governments. The port in El Salvador was cancelled due to international pressures.

- More simply, the construction delays and cancellations in Jamaica, Panama, and El Salvador demonstrate that the BRI is vulnerable to domestic political changes, civil society movements, or international pressure.

The remainder of this article will examine seven port projects that include discussions of country background/context section, project strengths and shortcomings, and what this may signal about the future of the BRI.

BRI Port Projects in Progress

Panama - Delays and doubts

On June 12, 2017, Panama established diplomatic relations with China and was immediately welcomed to participate in Belt and Road construction by China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi. This was followed by Chinese investment in Panamanian ports and US pressure in September 2018 on Panama to be wary of China's BRI efforts. In May 2019, Panama's newly-elected President Cortizo renewed calls to develop Panamanian human capital and increase port competitiveness. However, Panama, beyond initial declarations, appears to be losing faith in China as projects associated with China are delayed or cancelled. These projects include a proposed train from Panama City to David and the expansion of an electric transmission line. Panama Ports Company, a subsidiary of the Chinese company Hutchison Whampoa that runs the Port of Balboa and Port of Cristobal in Panama, is being audited under suspicion of not paying the full amount owed to the Panamanian government. At the Port of Balboa, strikes in May 2018 and July 2019 due to union issues caused many ships to go to nearby ports of call, demonstrating that Panama may not be as essential of a transshipment hub as once believed. This trend of delayed BRI projects is visible in Panama's two BRI ports: the Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal and the Colon Container Port.

Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal (Panama City, Panama)

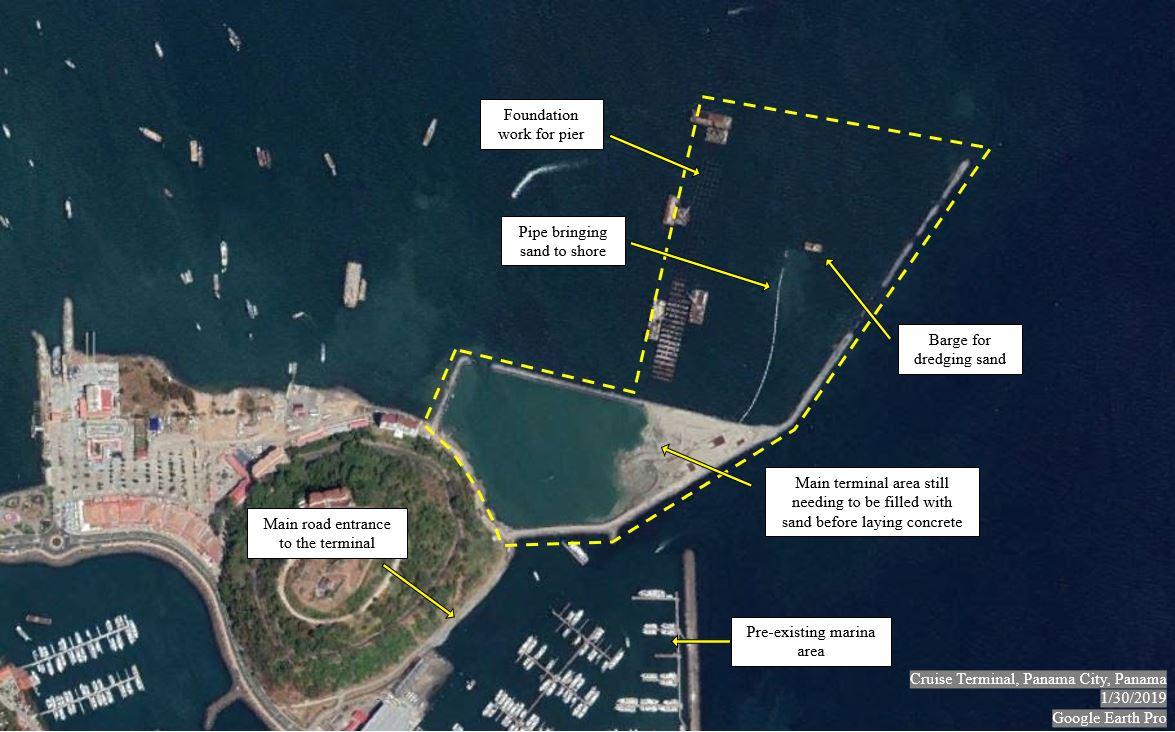

On July 31, 2017, less than two months after the establishment of diplomatic relations with China, China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) and Belgium's Jan de Nul were awarded a contract of $165.7 million USD to construct the Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal. This was the first government project by a Chinese state-owned enterprise since the establishment of diplomatic relations (CHEC is a subsidiary of China Communication Construction Company (CCCC)). Panama's former President Valera expected the cruise terminal to be completed in 2019, two years after construction began. The cruise terminal will be able to accommodate two large cruise vessels of 366 meters in length (other sources claim between 360 to 380 meters, but satellite imagery confirms the pier is 366 meters long) with a capacity of 5,000 passengers each.

In August 2018, the terminal was reported to be over halfway done as CHEC efficiently completed the dredging of the navigation canal and terminal area. However, satellite imagery from January 2019 to June 2020 shows that the port is now behind schedule. By January 2019, dredging was still occurring to build up the main section of the port and foundational work for the finger pier, named for its thin and protruding appearance, was still incomplete. As of late June 2020, the pier appeared to be mostly completed, with a single barge anchored near its end, but buildings in the main area of the terminal were still under construction. The sea wall on the eastern side of the port was also still incomplete, lacking the five wind turbines and light signal which are included in concept art of the port. The paving of a parking lot at the port and its main road entrance to the south will also need to be completed.

It is unclear why the port has been significantly delayed or when it will be completed. The cruise terminal may have had similar labor issues as the Port of Balboa did in 2018 and 2019. Alternatively, the lack of transparency in financial transactions that caused Panama to audit the Panama Ports Company may have been accompanied by a general distrust of Chinese companies using Panama money. One publicized issue has been a 2019 Panamanian government tender to find an operator and maintenance service for the Fuerte Amador port that had to be cancelled due to inconsistencies found in applications submitted by participating companies, a mistake which cost $9 million USD. A second attempt to find an operator and maintenance service through public bidding was temporarily suspended in April 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Container Port (Colon, Panama)

Similar to the Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal, the Panama Colon Container Port (PCCP) has been delayed for unknown reasons. In April 2019, CCCC confirmed that construction would now be compliant with Panamanian rules and estimated that the project would be completed in 2021, two years behind schedule. This statement insinuates that at one point CCCC's construction of the PCCP was not compliant with Panama regulation. Satellite imagery confirms this delay in the construction of PCCP. Through February 2018, only minor construction had occurred. On the southern side of the port, a barge was dredging sand to build up the quay area and deepen the entrance canal. To the north, what appeared to be administrative buildings with a giant CCCC logo in their courtyard had been completed. By March 2020, a year after the expected completion date, CCCC was still constructing the quay and terminal at the port. At the end of July 2020, the most recent available imagery shows no construction progress has occurred since December 2019. Trucks, cranes, and construction materials remain in the same place as 8 months ago, while debris and vegetation have begun to accumulate across the port area, even covering part of the CCCC courtyard logo.

On June 7, 2017, five days prior to the establishment of diplomatic relations between Panama and China, construction began on the Panama Colon Container Port on Isla Margarita in Panama. China's Landbridge purchased the port on May 25, 2016 for $900 million USD, but chose to delay construction of the project until diplomatic relations progressed between the two nations. This $1.1 billion USD construction project is being developed by China Communications Construction Company (CCCC). The port is a public-private partnership, a common practice in the BRI to attract capital. China's Landbridge is a private company that indirectly works with the BRI to support its goals, and CCCC is a state-owned enterprise. Phase 1, which was expected to be completed in mid-2019, will have a projected 2.5 million TEU handling capacity, a liquefied natural gas terminal, and four berths with a total quay length of 1.2km and a depth of 18m. After Phases 2 & 3, the port will have a 11 million TEU annual handling capacity, 3 docks (2 for Neo-panamax ships), a container yard, and 12 gantry cranes, 8 of which can handle Neo-panamax ships. It is unclear when Phase 1 will be completed and when Phases 2 & 3 will begin with the new delays.

As construction began occurring, there were questions from outside economic analysts of whether this port was a sound investment by China and a necessary project for Panama, as there is under-utilization of existing ports in terms of TEU on the Atlantic Coast of Panama. This suggests that emphasis should have been placed on fully utilizing existing ports instead of constructing new ones. The construction of PCCP may be a reaction to the expansion of the Panama Canal, which has new locks and doubled the capacity of the canal. Still, this BRI port promised to boost the local economy, as Panama's Ministry of Labor and Workforce Development of Colon claimed in 2018 that the port will create more than 2,000 jobs for locals, including 800 construction related jobs. It is still to be seen if construction resumes at the port after several delays and it meets its adjusted completion date in 2021.

Cuba - Passing grade

In recent years, Cuba has been working to attract more foreign investment. In 2014, Cuba's new Foreign Investment Act, Law 118/2014 allowed 100% foreign ownership of foreign-funded projects and a tax-exempt status for eight years if projects followed specific guidelines. However, there has been minimal foreign investment in Cuba, with the exception of Chinese financing. Cuba's dual currency system, where one currency is not internationally traded and the other is volatile, limits the profitability of projects and increases risk in investing. Secondly, the US has threatened to impose reciprocal sanctions against companies or countries investing in Cuba. China and Cuba have a longstanding relationship, and continuously China has demonstrated that the nation is willing to act against US interests, even with the threat of economic action. As noted in our Tearline report on Cuban energy projects, China's BRI projects in Cuba have been fairly successful, specifically in the renewable energy sector. The completion of these energy projects in Cuba depends on a stable source of capital from China and leadership from Cuban national and local governments.

Expansion of Cargo Port (Santiago, Cuba)

In January 2015, expansion of the cargo port in Santiago, Cuba began with a group of Chinese and Cuban construction specialists surveying the site. The port is funded by a $120 million USD loan from the Chinese government, the project is overseen by the state-owned China Communications Construction Company Ltd. (CCCC), and will be constructed by Chinese and Cuban laborers. The active phase of construction began in mid-2016, and was scheduled to be completed in three years. By August 2018, construction was almost complete and three Chinese-produced cranes were installed at the port. The port was completed on time and began operations on May 13, 2019.

The modernization of the port will make the port the second largest in Cuba and will allow the Port of Havana to be solely used for tourism. The modern port is almost fully automated and will incentivize ships to dock with lower payment per stay costs due to the increased efficiency. The port will boost the local economy with its increased capacity; including the addition of a 231-meter long pier, new dredged depth of 14 meters, 3 gantry cranes, 2 enclosed warehouses, an open air container space, and be able to process 5,000 tons of cargo a day. These specifics, announced in 2015, are visible in satellite imagery. By June 2018, the expected completion date for the port's foundational work, the quay had been constructed and storage areas were being developed. Imagery in February 2020 confirms that the rest of the project was completed on time and followed the original plans.

The port has already been incorporated into and supports the local community. The port reflects Cuba's needs for increased handling of cargo, is connected to the rest of the island through railways visible in the 2018 imagery, has employed local Cuban laborers, and ecologically benefits the surrounding rivers with a waste treatment plant that converts waste to potable water (projected). However, as of late July 2020 no clearly identifiable wastewater treatments are visible in satellite imagery. To the southwest of the port, there is an ongoing construction zone, but it is unclear if this is related to the port. The expansion of the cargo port in Santiago, Cuba is an accomplishment of Chinese financing, largely due to the level of coordination with local authorities and laborers, and paves the way for future BRI projects.

Antigua and Barbuda - So far so good

In September 2017, Hurricane Irma devastated Antigua and Barbuda, destroying approximately 90% of properties on the island of Barbuda. Following the storm, China invested heavily in rebuilding efforts and other sectors of the economy, especially tourism. Both countries appear to be invested in expanding the diplomatic relationship, which was cemented when Antigua and Barbuda joined the BRI in June 2018. Antigua and Barbuda have continued to ask Chinese companies and state-owned enterprises for investment, and China has continued to supply money and actively promote responsible investment, specifically the importance of upholding environmental standards, within its companies. However, the Yida project has inspired mass public opposition as the 2,000 acre special economic zone, that will include factories, homes, and resorts, largely ignores environmental safeguards, thus increasing Antigua's hurricane risk and destroying coastal vegetation home to many endangered animals.

Expansion of St. John's Deep Water Harbor (St. John's, Antigua and Barbuda)

Originally completed in 1969, St. John's deep-water cargo port, the main commercial port in Antigua to this day, became obsolete within two years of initial construction. The port was designed as a break bulk terminal, or a terminal that specializes in cargo that must be unloaded individually. By 1971, transporting cargo through containers was a widespread practice that St. John's deep-water cargo port could not fully engage in. By the time China agreed to expand and modernize the port in 2018, St. John's had been outdated and deteriorated for years. The old port, with an outdoor storage yard, outdated warehouse, and limited berthing and container-handling capacity can be seen in the below imagery from February 2018.

In January 2018, Antigua and Barbuda signed an agreement with China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation Ltd. (CCECC), a Chinese state-owned enterprise, to modernize the port. The Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), a Chinese state-funded and state-owned policy bank, will finance the $90 million USD contract with a low-interest loan. The project occurred as China was increasing its financial presence in Antigua and Barbuda following the September 2017 Hurricane Irma and just before the island nation officially joined the BRI in June 2018. Acknowledging complaints that China's BRI can be non-sustainable, delayed, and utilize primarily Chinese laborers, Antigua and Barbuda's Prime Minister, Gaston Browne, mandated that at least 40% of laborers must be local. There has been no recent public indication that China has not followed this mandate.

Construction began in April 2018 and is expected to be completed in mid-2021. Senator Mary Clare Hurst has said that the updated port will include an expanded quay, a new warehouse for processing goods, an extended sea wall, and other amenities. Satellite imagery shows that the ports construction is on-time and has not been hindered by other hurricanes. As of July 2020, the 320-meter quay expansion seemed to have been completed along with the new warehouse. On the northern side of the port, land has been built up for what is likely the new sea wall and a set of buildings and a parking lot have been constructed. To the south, another pier is being added to the existing cruise terminal, though it is not entirely clear if this expansion is also being funded and implemented by China. Importantly, the imagery shows that construction is still active even during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prime Minister Browne expressed enthusiasm that the port will be competitive with ports located at nearby islands. The modernization of St. John's has been necessary for decades and is only occurring as China has deepened its relationship with Antigua & Barbuda. China seems to have prioritized quality, efficiency, and following local regulations to preserve this relatively new relationship.

Trinidad and Tobago - Likely delayed

In recent years, Trinidad and Tobago has negatively spoken out against US actions, specifically US involvement in Venezuela. Coinciding with these events, both political parties of Trinidad and Tobago, The People's National Movement and United National Congress, have been economically, politically, and culturally expanding the country's relationship with China, which it has officially recognized since June 1974. When Trinidad and Tobago joined the BRI in May 2018, Prime Minister Rowley said, "We told them we need your investment and you need our location in the Caribbean." Trinidad and Tobago has worked to attract Chinese investment in many sectors, however, the termination of several projects suggests that China does not share the same positive view as Prime Minister Rowley. The cancelling of projects has left officials wondering if Chinese investment is the best solution to the economic issues on the islands; especially considering the lack of transparency surrounding these investments and the extremely generous concessions made to attract the investments.

La Brea Dry Dock (La Brea, Trinidad and Tobago)

On September 7, 2018, a few months after the country joined the BRI, the Government of Trinidad and Tobago signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the state-owned China Harbour Engineering Company Ltd. (CHEC) to build the La Brea Dry Dock facility over a four year period. CHEC will fund 30% of the port with a direct equity investment. Thus, reducing the financial burden on Trinidad and Tobago and, according to Prime Minister Rowley, giving CHEC a vested interest in ensuring that the port succeeds. There are concerns about the amount of debt the Trinidad and Tobago government has incurred, that La Brea is not an ideal location as ships along the traditional Caribbean shipping route require repairs elsewhere in the route, that CHEC has been blacklisted by the World Bank for bribery, and there is insufficient demand for the dock. CHEC has claimed that there is sufficient demand because the Panama Canal expansion will bring increased shipping to the Caribbean.

There was increased economic pressure for the Government of Trinidad and Tobago to partner with China for a large infrastructure project in the La Brea area after the Petrotrin oil refinery closed, causing over 5,000 people to lose their jobs and the region to lose its industry. The port will benefit the local area directly and indirectly. Once operational, it will generate $500 million USD annually, create training programs for community members on ports, support a more diverse local economy by consistently bringing in foreign business, and create thousands of jobs. This economic benefit, specifically the creation of 3,500 direct jobs and 5,700 indirect jobs during construction, is desperately needed in the region after the closing of the oil refinery. However, there is skepticism that the port will not generate the jobs that CHEC has announced for locals, due to the trend of importing Chinese laborers for large infrastructure construction associated with BRI, which is already occurring elsewhere in Trinidad and Tobago.

Per the Trinidad and Tobago government, the port will include two dry docks, a berth, land reclamation to support the proposed facilities, deep water dredging for the channel and turning basin, and necessary terminals to facilitate the operation of the port. However, despite the September 2018 agreement and the announced plans, our most recent imagery from late May 2020 shows that no construction has occurred, not even the beginning stages of land reclamation. The project has been further delayed by COVID-19 halting all foreign investment occurring in the spring of 2020. The indefinite delay of the project emphasizes how Trinidad and Tobago cannot build the port and bring business to the economically struggling La Brea area without Chinese aid. It appears that either the port is not a priority to the BRI or there are unpublicized reasons for its delay, as CHEC has continued to push back the project years after designs were finalized without any announcement about issues.

BRI Rejected Port Projects

Jamaica - The Impact of Civil Society

Leading up to and following Jamaica joining the BRI in November 2019, China has invested heavily in Jamaica. While the China-Jamaica official relationship is going well, there has been mass public discontent towards the negative effects of the infrastructure investments, such as immense debt, economic inaccessibility to Jamaicans, and serious environmental and human rights violations. One such example is the North-South Highway, a much needed infrastructure development completed in 2016,which left Jamaica with a $730 million USD debt to China and a fifty-year concession to recover the costs. Additionally, its $32 USD toll means that most Jamaicans cannot afford to drive on the road. Another example is the 2016 repair of the JISCO mine, which has brought large economic benefits to the local community, but currently has 16 violations for "causing serious environmental and human health issues." Richard Bernal, Jamaica's former Ambassador to the US, speaks out in support of the Chinese investment because the loan terms are generous, have low conditionality, are investing in much needed infrastructure upgrades, and there are few other investors loaning to Jamaica. The infrastructure may be necessary in Jamaica, but the negative impacts of the projects and limited economic profitability has left Jamaica in debt and many communities in upheaval against further BRI projects.

Transshipment Port (Goat Islands, Jamaica)

In August 2013, the Government of Jamaica announced that the state-owned China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) would be developing a transshipment port and industrial park on Great Goat Island and Little Goat Island. The project would have required leveling the island to construct the necessary infrastructure and extensive dredging to accommodate Super Post Panamax ships. Imagery below shows the location of the Goat Islands relative to Kingston in the east, as well as the islands' dense vegetation and shallow waters which would have been leveled and dredged, respectively.

While the idea for the project was announced in August 2013, the Initial Framework Agreement was signed in February 2014. It is important to note that the BRI did not formally begin until September 2013. The signing of an agreement for the Transshipment Port could not occur until the BRI was formalized. Almost immediately following the signing of the Initial Framework Agreement there was a grassroots campaign led by the Jamaica Environment Trust to save the Goat Islands. Not only are the islands an impractical location for a port, but they are also located in the Portland Bight Protected Area. Construction of a port would have removed all trees and the habitat for endangered species, left surrounding communities vulnerable to hurricanes, and destroyed small scale fisheries that sustain local communities. The Jamaica Environment Trust and other civil society organizations called on the Jamaican government to respect the environmental regulation of the protected area, publicize the proposed port plans, assess the environmental impact, include all relevant stakeholders in the decision process, and conduct a cost-benefit analysis for other potential locations for a port in Jamaica. In the 2016 Jamaican elections, there was a change in leadership and Prime Minister Andrew Holness announced that the Jamaican government would be cancelling the plans to build a transshipment port on the Goat Islands.

Jamaica and China's economic and diplomatic relationship has continued to grow, including Jamaica officially joining the BRI in November 2019. However, active civil society organizations and their impact on Jamaica's democratic government means that local communities are constantly influencing and limiting the extent of China's involvement in Jamaica. In February 2020, Senator Robert Morgan announced that the Goat Islands, due to their sensitive ecosystem, would become an animal sanctuary to preserve the habitat of many critically endangered species inhabiting the island. It is the continuous work of grassroots movements that transitioned the islands from being home to a massive port to an animal sanctuary. It is unclear if CHEC is planning on relocating the port project.

El Salvador - International Pressures

In August 2018, El Salvador severed diplomatic ties with Taiwan and formed ties with the People's Republic of China. Almost immediately, tensions between the US and China impacted El Salvador. The US worked to change public opinion in El Salvador against China and the Trump administration continued to threaten El Salvador with cuts to aid, specifically highlighting how the nation has handled migration issues. In contrast, China invested heavily in El Salvador, including in a water treatment plant, to present itself as a beneficial economic ally. In July 2018, El Salvador's President Salvador Sanchez Cohen established a legal framework for a special economic zone spanning 26 municipalities and 13% of El Salvador's landmass, for which China had requested a 100-year lease. This zone, which was cancelled in 2019 under new President Nayib Bukele, would have enhanced China's participation in regional trade and potentially, according to the US government, could have significantly increased China's military potential in the region. When President Bukele took office in February 2019, he considered renewing relations with Taiwan, but China granted a new national stadium, a new national library, a water purification plant, and other infrastructure improvements to ensure the continuation of diplomatic ties. In December 2019, El Salvador joined China's BRI.

Expansion of Port (Puerto de la Union, El Salvador)

La Union Port was first built by El Salvador in 2010, with the intention of attracting international investment to expand and modernize the port. However, even with El Salvador's new investment laws in 2011, no company or country expressed interest in investing in the port. The imagery below from November 2018 shows the general under-utilization of the port's capacity with a mostly empty container yard and only one cargo ship berthed at the eastern end of the quay. This lack of interest first changed in August 2018 when El Salvador pivoted toward diplomacy with the PRC. Days after the announced diplomatic switch, China began negotiations with the Port Executive Autonomous Commission of El Salvador and Beijing's state-owned Asia Pacific Xuanhao (APX) expressed interest in leasing 180 acres of land to develop $100 million USD worth of projects within and around the port.

US concerns over Chinese influence increased in reaction to discussions of China obtaining the operational rights to La Union Port. In a warning to the Government of El Salvador, a spokesman from the US Department of State stressed that Chinese investment is often connected to "unsustainable debt, environmental degradation, importation of Chinese workers and corrupt practices." El Salvador ignored US threats and warnings until January 2020 when Japan threatened to withdraw $102 million USD in development assistance to El Salvador if operating rights for the port were given to China. Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe warned El Salvador's President Nayib Bukele about Chinese intentions, emphasizing US concerns that China may wish to use El Salvador's port for military purposes. El Salvador immediately cancelled the proposed Chinese port expansion.

In this case, we observe that international pressure can thwart some BRI efforts. This potential BRI port project was cancelled as a reaction to international pressures, demonstrating another major factor affecting China-BRI Recipient Nation relationships and the progress of BRI projects.

Conclusion

BRI investment in ports in Central America and the Caribbean has increased as Chinese trade along these shipping routes and general influence in the region increases. These port projects have seen relative success, with construction completed on time and at a high quality, when then there is coordination between China and the recipient country's government and goals are aligned. This is visible in the expansion of Santiago Port in Cuba and the expansion of St. John's Deep Water Harbor in Antigua and Barbuda, both of which followed expected construction timelines. Additionally, both projects had strict guidelines and plans prior to Chinese investment and construction. In these two cases, China, Cuba, and Antigua and Barbuda were all committed to the respective port projects and believed each would benefit from the expansions.

In contrast, the La Brea Dry Dock in Trinidad and Tobago has been delayed because the BRI goals do not match with the recipient country's national goals. Trinidad and Tobago proposed this project for a number of economic reasons. However, CHEC has been hesitant to fully commit to the project because the port's location is not advantageous. The remaining four projects in Panama, Jamaica, and El Salvador demonstrate other ways BRI projects can become indefinitely delayed. The Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal and Colon Container Port in Panama were delayed in reaction to the domestic political change of a new President whose priorities differed from his predecessor. The Transshipment Port in Jamaica was cancelled in reaction to a large civil society movement protesting the negative environmental impacts of the potential port. Finally, the expansion of Puerto de la Union in El Salvador was cancelled due to a monetary threat from Japan, that was encouraged by the United States. This international pressure was directly aimed at limiting Chinese economic power in Central America.

The success of a BRI project is not guaranteed nor is the growing Chinese influence in Central America and the Caribbean infallible. Successful negotiations, construction, and operation of BRI port projects depend on coordination and similar goals among the relevant stakeholders. Domestic political changes, civil society movements, or international pressure can disrupt BRI projects, causing them to be delayed or cancelled.

Data Collection Methodology

The Belt-Road Initiative Geospatial & Headline Tracking (BRIGHT) Project at William & Mary's geoLab specializes in the merging of text and location-based data on official BRI projects and related non-BRI activities in Latin America and the Caribbean. The downloadable spreadsheet marks BRI projects as official, informal, or private Chinese money. Please also see the BRIGHT Matrix that explains our categorizations. The KMZ and Shapefiles only contain project locations which were mappable at a high level of precision, typically above the third administrative boundary level of a country. Some projects are attributed at the national level and coordinates were not used in these cases. However, all projects are listed within the spreadsheet download.

BRIGHT follows a three-step approach to the collection, geocoding, and imagery acquisition of these activities, triangulating information from open sources and imagery. Our data undergoes several rounds of quality assurance to enforce inter-coder reliability and accuracy. Through blending human and data-driven methods of data acquisition and analysis, BRIGHT seeks to form holistic narratives of Chinese engagement in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Timeline

Apr 01, 2020

China Merchants Port Holdings gains ownership of Port of Kingston in Jamaica

Feb 08, 2020

Goat Islands (proposed port location) in Jamaica become an animal sanctuary

Jan 01, 2020

Japan threatens to withdraw aid, El Salvador cancels port project

Dec 01, 2019

El Salvador joins the BRI

May 13, 2019

Construction completed on the expansion of Santiago Port in Cuba

Apr 01, 2019

Jamaica joins the BRI

Sep 01, 2018

Memorandum signed for the La Brea Dry Dock in Trinidad and Tobago

Source(s): Government of Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Works and Transport, La Brea Dry Docking Facility,

Aug 23, 2018

Negotiations begin for the expansion of Puerto de la Union in El Salvador

Aug 01, 2018

El Salvador establishes diplomatic relations with China

Jun 01, 2018

Antigua and Barbuda joins the BRI

May 01, 2018

Trinidad and Tobago joins the BRI

Apr 01, 2018

Construction begins on the expansion of St. John’s Deep Water Harbor in Antigua

Nov 01, 2017

Panama joins the BRI

Oct 01, 2017

Construction begins on the Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal in Panama

Jun 12, 2017

Panama establishes diplomatic relations with China

Jun 07, 2017

Construction begins on the Colon Container Port in Panama

Sep 01, 2016

Transshipment Port in Jamaica cancelled

Jun 01, 2016

Construction begins on the expansion of Santiago Port in Cuba

Sep 07, 2013

China's Belt and Road Initiative Launches

The Initiative was first called One Belt, One Road (OBOR). In Chinese it is called 一带一路.Source(s): Belt and Road Portal,

Aug 01, 2013

Negotiations begin for the Transshipment Port in Jamaica

Graphs

Chinese Companies involved in BRI ports projects

| Company Name | Abbreviation | Affiliation | Ports Constructed | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China Harbour Engineering Company Ltd. | CHEC | Subsidiary of CCCC | Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal in Panama; La Brea Dry Dock in Trinidad & Tobago; Goat Island Port in Jamaica | Implementer and Funder |

| China Communications Construction Company Ltd. | CCCC | A Chinese state-owned enterprise | Colon Container Port in Panama; Expansion of Santiago Cargo Port in Cuba | Implementer |

| Export-Import Bank of China | CHEXIM | A Chinese state-funded and state-owned policy bank | Expansion of St. John’s Deepwater Harbour Port in Antigua & Barbuda | Funder |

| China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation Ltd. | CCECC | A Chinese state-owned enterprise | Expansion of St. John’s Deepwater Harbour Port in Antigua & Barbuda | Implementer |

| Landbridge Group Co., Ltd. | Landbridge | A Chinese private enterprise | Colon Container Port in Panama | Funder |

| Asia-Pacific Xuanhao | APX | A Chinese state-owned enterprise | La Union Port in El Salvador | Funder |

Source: Original work by W&M geoLab

BRI Ports Activities

| Activity Name | Funder(s) | Implementer(s) | Location | When the country joined the BRI | Cost (USD) | Start Date of Construction | Activity Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuerte Amador Cruise Terminal | CHEC | CHEC and Jan de Nul (Belgium) | Panama City, Panama | 11/2017 | 165.7 million | 10/2017 | Under construction, behind schedule |

| Colon Container Port | Landbridge | CCCC | Colon, Panama | 11/2017 | 900 million | 6/2017 | Under construction, delayed |

| Expansion of Santiago Port | The Government of the People's Republic of China | CCCC | Santiago, Cuba | 2019 | 120 million | 6/2016 | Completed on time, 5/2019 |

| Expansion of St. John's Deep Water Harbor | CHEXIM | CCECC | St. John's, Antigua & Barbuda | 6/2018 | 90 million | 4/2018 | Under construction, on time |

| La Brea Dry Dock | CHEC (30%) and the Government of Trinidad and Tobago (70%) | CHEC | La Brea, Trinidad and Tobago | 5/2018 | 500 million | 9/2018 (memorandum signed) | No construction yet, delayed |

| Transshipment Port | The Government of Jamaica | CHEC | Goat Islands, Jamaica | 4/2019 | N/A | 2/2014 (Initial Framework Agreement signed) | Cancelled |

| Expansion of Puerto de la Union | APX | N/A | Puerto de la Union, El Salvador | 12/2019 | N/A | 9/2018 (negotiations begin) | Cancelled |

KMZ

Contains all mappable data points. Some projects are not listed because they lacked geo-coords below the national level.

Source: Download KMZ

Look Ahead

Please download the structured data in the Data Sources section. We plan to supplement the downloadable structured data with an interactive visualization later in 2020. We will update this report when this is ready.

Things to Watch

- Further Chinese investment in ports in Central America and the Caribbean

- How COVID-19 impacts construction timelines

- Whether further construction occurs in the three delayed ports in Panama and Trinidad & Tobago

- If a new port project is proposed to replace the cancelled projects in Jamaica and El Salvador

- Release of version 1.0 of the BRIGHT interactive visualization