Overview

In contrast to our findings of BRI hydroelectric power projects in Bolivia, in Ecuador, we observe fewer problematic environmental impacts in the majority of Chinese projects, with several accompanied by substantial local community development initiatives.

Some projects have experienced construction delays, with two of the largest activities also subjected to rampant corruption. Negotiations have occurred primarily at the national level, resulting in a more cohesive energy development strategy overall. However, corruption by the former Correa administration impacted project progress and quality.

Activity

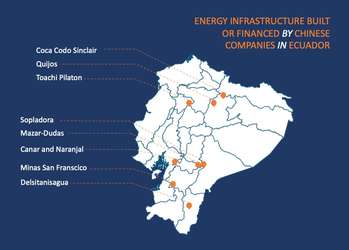

This Tearline article from the College of William & Mary's geoLab discusses findings from a project which utilizes open-source data collection and imagery analysis to study the impacts of Chinese development financing in Latin America and the Caribbean. The article examines evidence of eight hydroelectric power projects and/or dams in Ecuador in order to gain an understanding of Chinese actions and hypothesize Chinese intentions in the region. Satellite imagery shows that five of the projects have been completed. However, for the other three projects, our analysis indicates that construction has been paused for a significant amount of time. These indefinite delays are partially due to corruption in the Ecuadorian government and the projects themselves. Our assessment of the conditions of these BRI projects is based primarily on government data, then verified by imagery analysis and other open-source material due to the Ecuadorian national government's direct involvement in four of the projects.

In 2013, Xi Jinping launched China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a series of infrastructure investments and diplomatic endeavors that would be the guiding force for China's foreign policy. According to the Chinese government, the BRI seeks to promote political trust, economic integration, and cultural inclusiveness throughout the global community. The BRI assumes that the integrated economic development financed by China will create, or reinforce, a peaceful, cooperative international community and increase the economic prosperity and living standards of local communities participating in BRI activities. If this assumption holds true, the BRI has the potential to have a significant impact due to its unprecedented size: the BRI is composed of at least 3,485 projects across 138 countries, with over 273.6 billion USD in official Chinese financing. However, the BRI has been heavily criticized for its imposition of Chinese ideals, quality of implementation of the projects, and the relative success of the projects.

The BRI is primarily concentrated in the Afro-Eurasia geographic regions, most notably along six highlighted economic corridors. As the BRI has grown, projects are no longer solely located in these corridors--a trend most visible in the BRI's expansion to Latin America & the Caribbean. As of 2021, 19 countries in this region have signed a formal Memorandum of Understandings (MoU) with China to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Globally, many BRI projects have occurred in the energy sector, seeking to improve energy security and meet the energy needs for potential industrial expansion. If these energy projects are from renewable sources--which the Chinese government announced as a goal of the BRI in May 2017--then the BRI has the ability to transform energy sectors to favor low-carbon emitting sources in recipient countries and aid these countries in meeting the United Nations Paris Climate Agreement's outlined sustainability goals. However, a significant portion of BRI energy projects is still fossil fuel-based. In Latin America, even the non-fossil fuel energy projects--such as hydropower, which accounts for 71% of the world's supply of renewable energy--financed by China carry their own significant environmental consequences. Leaving the question of whether the title of low-carbon emitting energy source automatically indicates a certain level of environmental sustainability.

In Ecuador, the shift in energy resources to prioritize hydroelectric power began when the Ecuadorian Ministry of Energy and Non-Renewable Energy (MEER) was created in 2007, re-opening the once privatized Ecuadorian energy sector. This prioritization was reiterated in MEER's 2012 to 2021 electrification plan. These actions were complemented by Ecuador's new constitution in 2008, known as the 'Buen Vivir' [the 'Good Life'] constitution; it echoes the indigenous philosophy of a "community-centric, ecologically-balanced and culturally-sensitive" existence. The constitution prioritizes indigenous rights, environmental sustainability, and state sovereignty. The development plan based on the constitution outlined the goal of "energy sovereignty" primarily through the development of hydroelectric power in order to reduce dependency on "both Western creditors and on a petro economy."

Former President Rafael Correa's objective was to scale down Ecuador's dependence on thermoelectric power and fossil fuels and produce enough energy to meet domestic energy needs as well as export electricity to neighboring countries. Further, between 2021 and 2022, Ecuador is planning to export 8% of the energy generated by hydroelectric power projects (HPP). In 2015, Vice President Jorge Glas stated that once all projects are constructed and running, hydroelectric energy would account for 93% of the nation's energy production. To achieve this objective, Correa sought out greater hydroelectric power opportunities with China's help, resulting in the construction of eight major dams.

While BRI investments in Ecuador largely began with the inauguration of the BRI in 2013, Ecuador's then-President Lenin Moreno formally signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China's Xi Jinping on December 13, 2018. This formal agreement has strengthened Ecuador and China's relationships and increased the presence of the BRI in Ecuador. Beyond hydropower, BRI projects in Ecuador have primarily aimed to restore general infrastructure and mining operations destroyed by the April 2016 7.8 magnitude earthquake in northern Ecuador.

There are currently eight Chinese-associated HPPs in Ecuador. This paper will analyze these eight projects in terms of interactions with the environment, local community impact, and legal issues (all scores on these indicators are visible in the accompanying scorecard). We will additionally compare how the BRI operates and its relative success in the hydropower sector in comparison to Bolivia.

Summary of project outcomes:

- Construction is complete at four of the eight projects (Sopladora, Minas San Francisco, Delsitanisagua, and Canar & Naranjal). During construction, there were minimal environmental impacts, positive community development initiatives, and limited corruption.

- Construction at two of the eight (Mazar-Dudas and Quijos) projects has been delayed since December 2015 due to contract terminations. During the delays, there have been substantial positive community development initiatives but some negative environmental impacts.

- Construction is complete at one of the eight (Coca Codo Sinclair) projects but was hindered by corruption along with both negative environmental and local community impacts.

- Construction at one of the eight (Toachi Pilaton) projects has been delayed due to corruption. There were negative impacts on both environment and local communities.

Lessons to take away from these BRI projects:

- Ecuadorian government oversight successfully mitigated some of the negative environmental and community impacts of hydroelectric power projects and dams. Additionally, this oversight led to two contract terminations for non-compliance.

- Pervasive Ecuadorian federal-level corruption impacted many project facets.

- Ecuador's continued debt to China, initiated by Correa's 2008 default and rejection of Western finance, has created a dependency on China. If Ecuador wishes to rejuvenate its diplomatic and economic relationship with the United States, as indicated in the actions during the first half of 2021, a new policy direction must be taken.

Methodology

In this article, and the previously released case study on hydropower in Bolivia, each BRI project was analyzed in the context of the environment, community impact, and legal indicators. These three indicators were then broken down into relevant success factors. For each success factor, each project was ranked as unsuccessful (0), neutral (1), or successful (2). To rate the overall impact of the dams, the scores for each project were averaged out, creating a scaled ranking of unsuccessful (0 - 0.68), neutral (0.69 - 1.34), and successful (1.35 - 2). For more information on the specific rankings for each project and success factors, see the scorecard of hydro project factors and our BRI threshold matrix to see what factors we used to classify projects as BRI or not. For more information on other aspects of the projects themselves, including financing and construction status, see the tables in the Graphs section.

Structured Data

In addition to this case study narrative on hydro projects in Ecuador, we created 160+ points of locational and structured data of official BRI projects and related non-BRI activities in Latin America and the Caribbean. The downloadable spreadsheet marks BRI projects as official, informal, or funded by private Chinese money. The KMZ and Shapefiles only contain project locations that were mappable at a high level of precision. Some projects are attributed at the national level and coordinates were not used in these cases. However, all projects are listed within the spreadsheet available.

The Ecuadorian Context

Inaugurated in 2007, left-wing, anti-imperialist populist turned President Rafael Correa announced his goal of "[freeing] Ecuador from the orbit of the United States." Correa quickly separated Ecuador diplomatically from the United States by refusing to renew an agreement for a US military base in Manta and declaring the US Ambassador to Ecuador as a persona non grata. Financial ties were severed in late 2008 when Correa canceled 3.2 billion USD in debt to the IMF because the debt was "immoral and illegitimate," according to Correa himself. With oil prices low, the world in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis, and Ecuador still deep in debt, Ecuador turned to the only lender willing to interact in a high-risk environment, China.

While Correa had no access to foreign capital, a serious issue since Ecuador utilizes the US dollar as its official currency, he did have oil. Ecuador has the third-largest oil reserves in South America, after Venezuela and Brazil, and was estimated in 2013 to have produced approximately 550,000 barrels per day for an export amount of 11.9 billion USD. In 2008, to gain access to this seemingly unlimited line of Chinese credit from state-owned banks, Ecuador granted almost 90% of its oil exportation for the foreseeable future to China. This action, and Ecuador's quickly booming relationship with China, stands in direct contrast to the ideals outlined by the 2008 'Buen Vivir' [the 'Good Life'] constitution.

From 2005 to 2013, prior to the inauguration of the BRI, China accounted for 57% of all foreign investment in Ecuador. Under Correa, who was in power from 2017 to 2021, Ecuador borrowed over 19 billion USD from Chinese banks for BRI projects, each of these loans is opaque and contains high-interest rates. In 2016, China became Ecuador's largest bilateral debt holder. China and Ecuador economically benefited from each other, with China supplying billions in much-needed credit to Ecuador in return for oil and a profitable outlet for Chinese companies. Instead of using this oil as a resource in China, as Ecuador assumed was the plan, China sold it to regional markets in the Western Hemisphere at a profit.

Inaugurated in May 2017, Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno chose to slightly de-emphasize Ecuador's dependence on China. Other nations, including Turkey, are attempting to "balance China out by increasing foreign relations with other nations," in hope of reducing dependency on China. Moreno's energy minister Carlos Perez publicly stated that "China took advantage of Ecuador. The strategy of China is clear. They take economic control of countries." However, throughout Moreno's term in office, he continued to borrow money from China, notably visiting China in December 2018 to both renegotiate Ecuador's debt and borrow another 900 million USD. Correa, in a fiery Twitter response to a New York Times article about Ecuador's debt to China, called the newspaper a "charade" with "ludicrous" claims, arguing that "Ecuador is a good Latin American example of how to establish sovereign and mutually beneficial relations with China."

Under Moreno, Ecuador's attempt at reforming a diplomatic relationship with the US was positively received, as the US began developing a policy to actively counteract Chinese intentions and actions in Latin America. In December 2019, the US State Department pioneered the "America Crece" plan which seeks to "leverage existing programs [and] diplomatic engagement" in order to grow US influence. In January 2020, a week before Biden was inaugurated as the US President, the US Development Finance Corporation signed an agreement with Ecuador's then-President Moreno for 2.8 billion USD to, according to US officials, "refinance predatory Chinese debt" and support private sector investment. The agreement also prohibited Ecuador from purchasing Chinese tech products. This all paired with the perception that China's explosive growth is faltering and may lead to a decrease in BRI project financing. However, the strength of the Chinese economy and its ability to lend is somewhat hindered due to the lack of transparency. Regardless of the financier, Ecuador is "trapped once again in the vicious cycle of debt: contracting new debt to pay the old."

Experts analyze that this agreement sought to directly influence the first round of Ecuador's presidential election in February 2021 and influence the country to not vote for the current leading contender Andres Arauz, a supporter of Correa who promised: "to reverse Moreno's fealty to the United States and his subordination to the IMF's deflationary policies." At any rate, Arauz did not win the election.

Inaugurated on May 24th, 2021, Guillermo Lasso, Ecuador's first center-right president in two decades, is a market-friendly banker, a stark contrast to Ecuador's recent history with populists. Unlike his presidential predecessors, Lasso is shifting away from Chinese support and backing, focusing more on (re)building Ecuador's relationship with the U.S. while still maintaining good rapport with China. However, Ecuador cannot fully let go of China. In terms of hydroelectric power, the appointment of Juan Carlos Bermeo as Lasso's Minister of Energy, a former executive of Petroamazonas, indicates that Ecuadorian policy in the hydroelectric sphere will remain the same.

Environment

While hydroelectric power projects are a non-fossil fuel emitting renewable energy source that can significantly reduce a region's carbon emissions, these projects can have negative impacts on the environment. Recent academic research, primarily focused on the Amazon and Mekong River basins, has found a pattern across the several studied projects of "disrupting river ecology, deforestation, losing aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity, [and] releasing substantial greenhouse gases." More specifically, HPPs in the Andean headwaters of the Amazon, which several of the BRI projects in Ecuador are located, threaten the habitats of 671 freshwater fish species and the level of sediment downstream in the Amazon basin. The decrease of sediment contribution "[translates] to drastic alteration of river channel and floodplain geomorphology and associated ecosystem services."

In Ecuador, droughts have been a continuous problem due to El Nino and La Nina phases, impacting HPPs' capacity to generate electricity and challenging the government to find ways to supplement this loss and lack of electricity. Even with this knowledge of environmental conditions and implications, the Correa and Moreno administrations both continued to support the Chinese constructed hydroelectric power projects. The environmental impacts of these projects in Ecuador are similar to those in Bolivia, however, per our rating system detailed on the scorecard, HPPs ranked higher in Ecuador than in Bolivia.

This section will discuss the project-specific interactions with the environmental indicators listed on our scorecard: air, land, water, and biodiversity. These three dams--Coca Codo Sinclair, Mazar-Dudas, and Quijos--were chosen due to the relative wealth of open-source information surrounding them. For more information on the environmental interactions of all eight of the projects, see the scorecard.

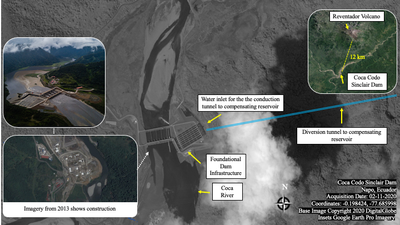

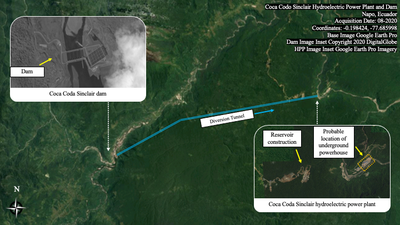

Coca Codo Sinclair

The Coca Codo Sinclair dam is the largest hydroelectric power project in Ecuador and is the largest project funded by the China Export-Import Bank (CHEXIM) in Ecuador. The HPP was proposed by the Ecuadorian government in 1976, but due to financial constraints and the eruption of the nearby Reventador volcano in 1987, construction on the HPP did not begin until 2010. Of the 2.6 billion USD construction cost, CHEXIM loaned the Ecuadorian government 1.68 billion USD that is payable within 15 years. The remaining funds were provided by the Ecuadorian government. The hydroelectric power complex has the potential to generate 1,500 megawatts (MW), which would supply nearly 35% of the country's electricity. This would lead to a yearly reduction of 4.43 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Even though the project has been operational and producing power for the electrical grid since its opening in November 2016, the HPP has failed to produce the expected amount of energy. Several days after its official opening, a full capacity test was attempted. The equipment did not perform well and "shuttered" causing rolling blackouts across the country. The test did aim for full capacity but the local power grid could not handle the full output. There are no published plans for the HPP to operate at its full capacity of 1,500 MW, however, a July 2019 statement by CELEC announced that "Ecuador will definitively not take over the plant until all the works permitting Coca Codo Sinclair to operate normally have been carried out." The efficiency of the HPP has been partially compromised due to its proximity to the active Reventador volcano, as visible in the inset in the February 2020 satellite image, causing 7,648 cracks in the infrastructure as early as 2014, two years prior to the completion of the construction. There is no information indicating that attempts were made to remedy these and prevent further cracks. Instead, the senior Ecuadorian engineer who recorded these cracks and sent them to Correa was fired a few days later.

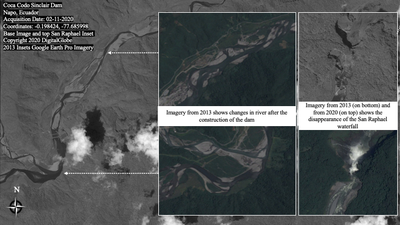

Since the dam's construction began in 2010, the negative impacts on biodiversity and river flow are fairly evident. Erosion on the banks of the river and the surrounding area is at the heart of the environmental degradation caused by the construction of the HPP. Geologists hypothesize that the Coca Codo Sinclair HPP caused an imbalance to the Coca River, inciting fast-moving erosion upstream and consequently, the disappearance of the San Rafael waterfall. In April 2020, an oil spill, some have attributed to landslides caused by the loss of the San Rafael waterfall, of over 15,000 gallons not only polluted the waters and destroyed wildlife, but has since impacted over 150,000 people, many of whom are Kichwa indigenous people. Everything from peoples' food sources, livelihoods, health, and farming lands has been contaminated by the spill. Furthermore, the landslides have raised concerns in the nearby town of Cuyuja to fear that the dam's transmission towers may topple over. Geologists suspect that the tower foundations were not built into the bedrock by the Chinese. At any rate, a 2008 independent study by an environmental group raised many of these concerns and implications.

The Coca Codo Sinclair dam has diverted some of the Coca River flow, as visible in the February 2020 satellite image. This, in tandem with sediment discharge and the disappearance of the San Rafael waterfall, also visible in the February 2020 satellite image, could have significant negative impacts on species loss. That being said, the national government has implemented a program to "restore and revegetate" biodiverse areas that were impacted by the infrastructure. It is unclear what the scope of this project is and whether it can successfully balance out the negative impacts of the dam.

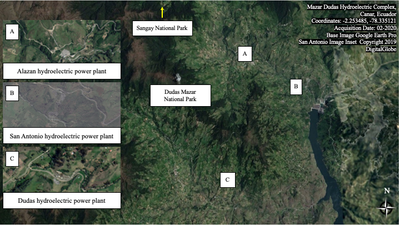

Mazar-Dudas

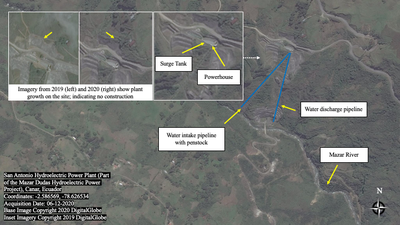

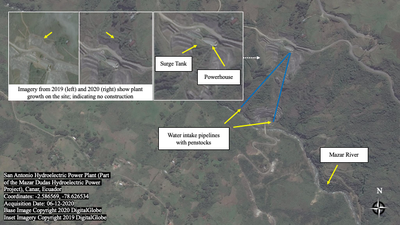

Funded by a 41.6 million USD loan from the China Development Bank (CDB) in 2012, the run-of-the-river Mazar-Dudas hydroelectric complex is located along the Pindilig and Mazar Rivers, as visible in the February 2020 satellite image. The complex, composed of the 6.23 MW Alazan HPP, 7.19 San Antonio HPP, and 7.40 Dudas HPP, will generate a total of 21 MW. The hydroelectric complex will reduce carbon emissions by 60,768 tons annually. Due to contractual issues, the project has been halted since December 2015, with only the Alazan HPP--connected to Ecuador's energy grid in April 2015--as operational.

Set to be built in a protected area, the HPPs could pose a threat to the Dudas-Mazar forest, highlighted in the February 2020 satellite image, which is home to hundreds of species of flora, fauna, and trees. However, in contrast to Coca Codo Sinclair, these three HPPs are run-of-the-river, meaning the projects include smaller dams, and thus, have a smaller impact on the course of the river and threat on the ecology of the Dudas-Mazar forest--an undeniable positive for minimizing the environmental impact. This is important to note as the way an HPP is constructed directly impacts the project's interactions with the environment. However, the construction of a run-of-the-river HPP is dependent on the geography of the river and the amount of energy desired. This type of HPP was not possible, for instance, for the Coca Codo Sinclair project. Additionally, the preliminary construction of Mazar-Dudas led to some geological issues as rock drilling occurred. The environmental impact assessment, carried out prior to the project's construction, did not initially anticipate these geological issues, which have directly impacted the cost and timeline of the project's implementation.

Quijos

Similar to the Mazar-Dudas hydroelectric power complex, the Quijos hydroelectric power project was funded by the China Development Bank (CDB), constructed by China National Electric Engineering Company (CNEEC), and overseen by Corporacion Electrica del Ecuador (CELEC), all of which are state-owned enterprises in their respective countries. Construction began in 2012 and was expected to be completed in March 2016. Due to contractual issues, the project has been halted since December 2015 and remains uncompleted, as visible in the December 2020 satellite image. The project is estimated to cost 115 million USD. CDB is financing 94.7 million USD. The project will have the capacity to generate 50 MW of electricity.

Quijos HPP will have both positive and negative impacts on the environment. The project, upon completion, will reduce yearly carbon emissions by 180,000 tons, a positive. However, the project requires tunnels to be built, including the already visible diversion tunnel seen in the imagery, passing through a "geologically unstable" mountain to guide the flow of two rivers' water into penstocks downstream, a negative. Building tunnels through unstable mountains can lead to collapse, landslides, avalanches, and greater geohazards. The Quijos HPP, like the Coca Codo Sinclair complex, is also thought to threaten the San Rafael waterfall. This would have an impact on the native plant species that depend on natural river fluctuations.

Local Community Impact

Hydroelectric power projects can have the potential to significantly impact the communities living around the project because many depend on the rivers' resources for their food and livelihoods. More specifically, the environmental changes caused by an HPP can lead to the displacement of thousands of people and alter livelihoods through the project's impact on food systems, water quality, and agriculture.

To mitigate this threat to communities' food and economic security, many of the BRI hydroelectric power projects and/or dams in Ecuador are accompanied by several social and economic development programs and initiatives. These programs appear to improve local communities' livelihood through the creation of jobs, improvement of infrastructure and increasing access to electricity. These initiatives stand in stark contrast to the BRI projects in Bolivia, where no community development programs accompanied the HPPs. Our analysis indicates that this vast difference is due to the different approaches of the recipient country's federal governments. Ecuador mandated that projects include these initiatives, and often financed and implemented the initiatives themselves, even though Chinese SOEs were the primary implementers for the infrastructure projects.

This section will discuss the project-specific interactions with these community impact indicators: labor, local communities, social development, economic growth, energy, and infrastructure. These four projects--Sopladora, Delsitanisagua, Canar and Naranjal, and Minas San Francisco--were chosen due to the relative wealth of open information surrounding them, especially media coverage focused on highlighting community impacts. For more information on the community interactions of all eight of the projects, see the scorecard.

Sopladora

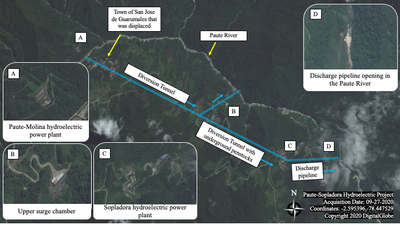

The Sopladora hydroelectric power project is the third-largest hydroelectric power project in Ecuador, with an expected capacity of 487 MW. The project does not include a dam as it instead relies on water discharged from the nearby Paute River. In 2011, the CHEXIM granted a loan of 571 million USD for the construction of the project, covering 85% of the total cost, while the other 15% was financed by Ecuadorian sources. China Gezhouba Group, a Chinese state-owned enterprise, and the private Ecuadorian company Fopeca constructed the project. The Ecuador state-owned operator, Corporacion Electrica del Ecuador (CELEC), carried out studies of the physical, environmental, social, and archeological impacts of the project within a 1,318-hectare area surrounding the project. Because the project is completely underground, negative impacts, in terms of both the environment and community development, were minimal because there are fewer dependencies when compared to above-ground projects. In August 2016, the plant was inaugurated and started generating electricity.

There was a significant amount of Ecuadorian labor involved within the project even amid the nominal contractual requirements that the Sopladora HPP must be built by Chinese companies using Chinese equipment and labor. Locally, 746 jobs were created along with 2,000 additional jobs generated for Ecuadorians from other parts of the country, a positive for the Ecuadorian economy. Most of the project's managers and high-skilled laborers were directly from China, while the low-skilled labor was occupied by Ecuadorians. There were more Ecuadorian laborers than Chinese laborers, with eight out of ten workers at Sopladora as Ecuadorian. In general, the project management and higher construction salaries went to the Chinese laborers. Additionally, this model does not facilitate knowledge transfer to Ecuadorian workers, creating a further dependency on Chinese companies, a negative, especially in regards to Ecuador's desire of sovereignty in development, as outlined in the 'Buen Vivir' constitution. The construction site had few safety precautions in place, leading to the death of seven workers during the project's construction: a failed attempt to expand a well with explosives killed four Chinese workers in addition to three lives lost due to undisclosed activities.

The Sopladora HPP included positive improvements to local infrastructure, which are expected to benefit 800,000 people in the surrounding areas. The improvements include educational infrastructure projects, upgrades to health facilities, the construction of new roads, and the construction and improvement of drinking and sanitation systems. These projects were executed by CELEC, not the Chinese SOEs involved with the project, despite the fact that the Chinese SOEs are the primary funder and implementer for the project. However, on the negative side, local family farms on the site and residents of the town of San Jose de Guarumales were displaced by the project's construction. As seen in the September 2020 imagery, the diversion tunnel passes right through the town. To balance this loss of home and livelihoods, as these communities were dependent on the river for food and economic security, CELEC promised to execute training in tourism and strengthen the capacity of agricultural and livestock.

Delsitanisagua

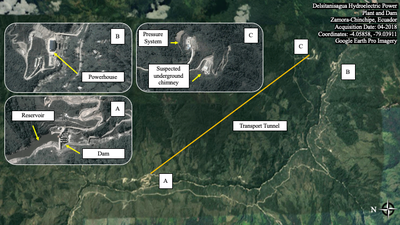

In 2011, CDB financed the construction of the Delsitanisagua HPP and dam, which has a generating capacity of 180 MW with three turbines. CDB granted 185 million USD for the project, however, the actual cost of the project increased by 55% during construction. This increase violates Ecuadorian law, which restricts project costs to stay within 35% of the amount dictated by the original contract. It is unclear how the Ecuadorian government chose to finance the rest of the project and whether CDB chose to grant or loan more capital, but it is clear that the Delsitanisagua hydroelectric power project placed a large financial burden on Ecuador. One source said that Ecuador may have repaid money loaned from CDB with oil sales for Delsitanisagua, which Ecuador has done for other BRI projects due to Ecuador's loss of access to international capital markets following its 2008 default.

China's state-owned HydroChina, a hydropower and engineering company, led the construction of the project. Because of the unanticipated cost increase of the project, halfway through implementation, Hydrochina's contract increased from 195 million USD to 258 million USD. Two years after the project's expected completion date, the HPP was inaugurated in December 2018, and generated more than 829 gigawatts/hour of energy to Ecuador's National Interconnected System (SIN) in its first year of operation. However, this energy production has not been consistent, as the project has halted operation multiple times, including in May 2020 to clean the reservoir due to sediment accumulation interfering with the turbines. Imagery from late May 2020 shows that the dam did resume operation after being cleaned.

While the official number of project workers is unknown, 1,531 jobs were designated for local laborers. This project will directly positively benefit 91,376 inhabitants of the Zamora-Chinchipe province. The construction of the project, like many in Ecuador, is accompanied by community and social development initiatives, beyond the expansion of rural electric power networks that will benefit 1,606 inhabitants in the local communities. Associated initiatives and infrastructure improvements include 3 potable water systems, 129 basic sanitary units for 408 inhabitants, a wastewater treatment plant for 200 inhabitants, the construction of a communal house for 195 inhabitants, and multiple economic training programs to strengthen the economic capacity of these communities.

Canar and Naranjal

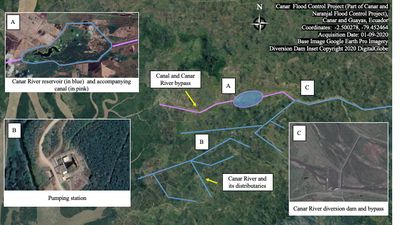

The Canar and Naranjal flood control projects were financed by the state-owned Bank of China and privately owned Chinese Branch of Deutsche Bank, and implemented by the state-owned China International Water and Electric Corporation (CWE) and Ecuadorian state-owned company Senagua. Signed in July 2013, the 298.9 million USD loan came attached with a high-interest rate of over 3.5%.

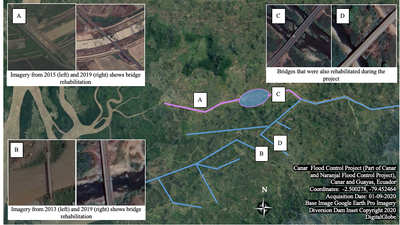

Construction on the project was completed in January 2016 and included a 23 km canal, a diversion dam, two newly constructed bridges, and upgrades to existing roads and other bridges. The infrastructure improvement of replacing old bridges is visible in the satellite imagery. While the project itself does not produce hydroelectric power, the project diverts river water into eight Chinese turbines that are estimated to produce enough electricity to power one-third of Ecuador through the national grid system. We chose to include this project in our hydroelectric power analysis because the primary purpose of the Canar and Naranjal flood control project was to improve the efficiency and efficacy of the nearby eight turbines.

This project is in itself a positive community development initiative, as it improved local infrastructure and protect communities from flooding. This flood defense project will protect 150,000 people and will save millions from the effects of extreme weather and climate change. Former President Correa said that these projects will "avoid the loss of 105 million USD in crops." The project will protect more than 40,000 hectares of fertile land.

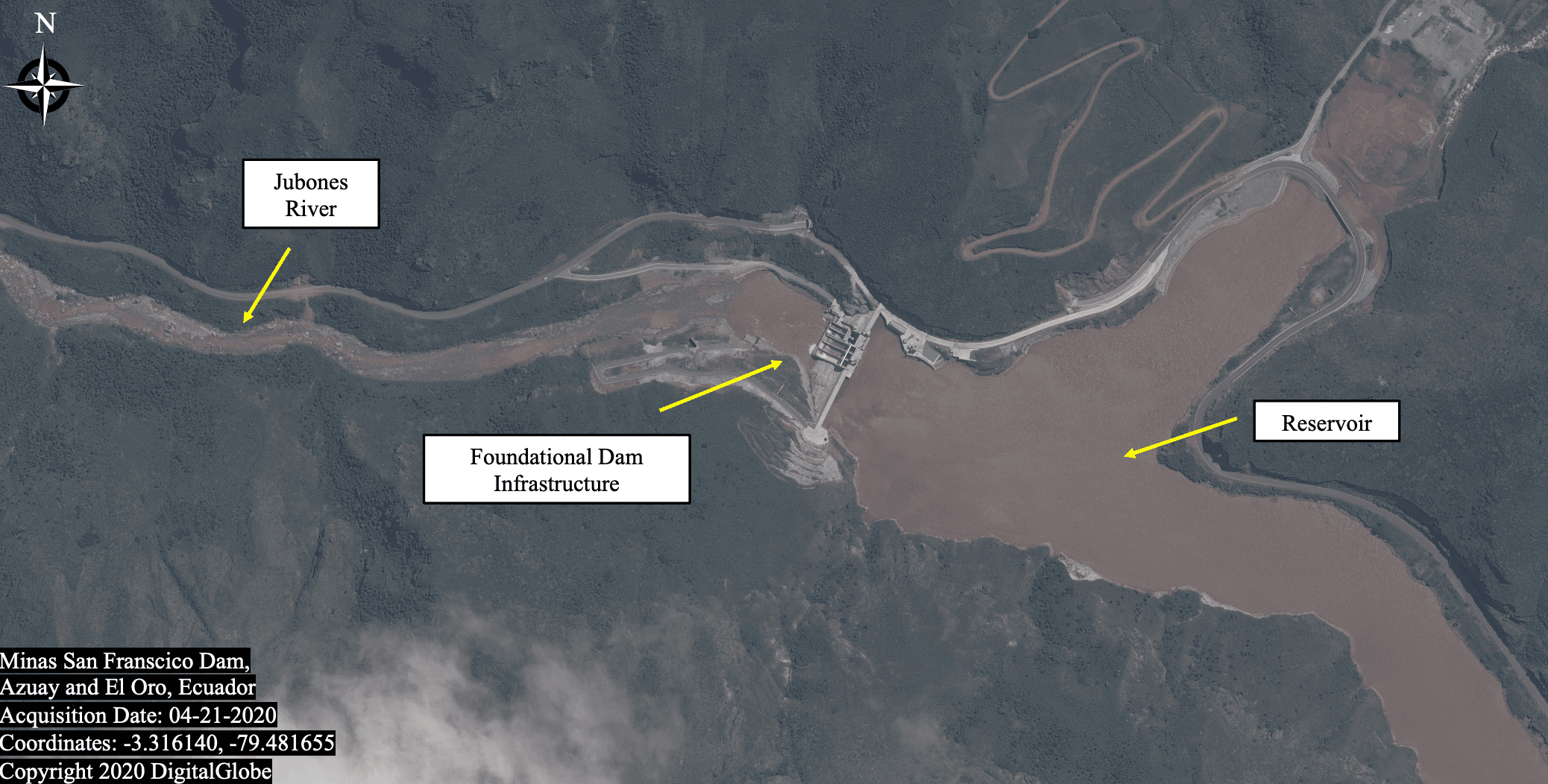

Minas San Francisco

Minas San Francisco was financed by CHEXIM in 2012 and constructed by the private Chinese company, Harbin Electric International. CHEXIM loaned 312.4 million USD as a line of credit with an interest rate of over 4%. However, the price tag of the project increased by 34% (barely below the legal limit of 35%) during construction to a final cost of 684 million USD. It is unclear how the project was funded beyond the CHEXIM loan. The plant's installed capacity is 270 MW, with three turbines that each have the capacity to generate 90 MW, and it has been operating at full capacity since construction completed in January 2019, three years behind schedule. In June 2020 the management of the project was handed over to Ecuador's CELEC.

The project provided 2,798 local jobs and an additional 13,500 jobs generated indirectly. a positive. The project's community development initiatives include increased accessibility to electricity, maintenance of basic services and sanitation systems, and training in improving agricultural productivity and techniques. These initiatives will positively benefit over 136,000 inhabitants of the local communities surrounding San Sebastian.

Minas San Francisco and some of the other discussed hydroelectric power projects and/or dams have balanced out the traditionally negative community impacts through an active effort to benefit local communities. These benefits can have positive impacts by improving economic security through job creation and training programs. In addition, local conditions are improved with new infrastructure.

Legal Issues

In our case study of Bolivia, we discussed how grassroots mobilization efforts successfully delayed projects. In Ecuador, there have been no mass mobilizations against hydroelectric power projects and/or dams. This is significant because like Bolivia, Ecuador has a recent history of large protests, most notably the October 2019 indigenous-led protests against changes in fuel prices that resulted in violence. One potential reason for this difference is the hydroelectric power projects and/or dams in Ecuador were almost always accompanied by social development programs and more respectful of indigenous homes and livelihoods. Instead, impediments to the progress and operation of projects have all occurred in a more formal arena in Ecuador with the federal government more actively involved.

This section will discuss the project-specific interactions with legal issues such as corruption and contractual agreements. The indicator of corruption was measured based on various legal findings of corruption related to these projects. It is possible that more projects were impacted by both federal and local levels of corruption, however, this possibility has not been proved in court, and thus, will not be discussed. These four dams--Coca Codo Sinclair, Toachi Pilaton, Mazar-Dudas, and Quijos--were chosen due to the relative wealth of open-source information surrounding them.

Coca Codo Sinclair

The Coca Codo Sinclair HPP generates a significant surplus of energy exported to neighboring countries such as Colombia and Peru. However, this dam has been plagued with problems, including 7,648 cracks and the facility was built near an active volcano. Coca Codo Sinclair EP (COCASINCLAIR EP), an Ecuadorian "state-owned special-purpose enterprise established in 2010," signed an Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contract with the Chinese state-owned Sinohydro. This EPC or "turnkey" contract stated that Sinohydro would have 66 months to construct and finish the project and would be responsible for subcontracting and importing required materials, equipment, services, and technology. Another report from Consulting Inspection Services, an American company, claims that the numerous structural problems were caused by the use of construction materials by Sinohydro that did not meet industry standards, which is in breach of the EPC contract.

Many serious challenges were faced during construction, including the death of 16 workers, multiple orders of suspension, and even a warning of termination of the contract due to engineering failures and non-compliance issues. After worker strikes at the construction site in 2011 and 2012, inspections by the National Assembly and a report by the State Comptroller both found violations of workers' rights. Furthermore, during the project, 14 civil lawsuits were filed against Sinohydro, and 92 labor claims, 80 of them being against Sinohydro and 12 against COCASINCLAIR EP. Sinohydro also failed to provide adequate training programs for the personnel operating the plant. These training programs were part of the contract Sinohydro signed. The project was completed and the contract was fulfilled, however, our evidence suggests that Sinohydro did not fulfill the duties expected of them. The only known legal action taken against China, is Ecuador's Ministry of Labor and the Social Security Institute fined Sinohydro the small amount of 5,280 USD. This measure, similar to other Ecuadorian state action taken in legal disputes at these BRI projects, was all reactive instead of proactive.

Almost every top Ecuadorian official involved in the project's construction has been either imprisoned or sentenced on bribery charges. Former Ecuadorian Vice President Jorge Glas Espinel was convicted of taking bribes from China's main competitor in the region, the Brazilian construction company, Odebrecht. An article from the New York Times says that Brazilian construction conglomerate Odebrecht "paid 33.5 million USD in bribes in Ecuador as part of a worldwide scheme to win business." The former electricity minister, Alecksey Mosquera is now serving a 5-year sentence for taking 1 million USD from Odebrecht.

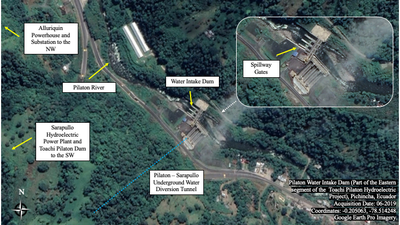

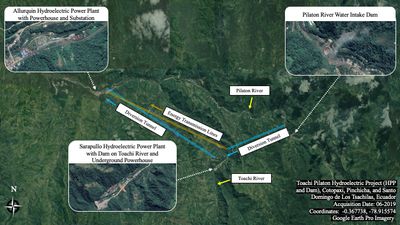

Toachi Pilaton

In February 2008, the first cornerstone was laid for the construction of the Toachi Pilaton hydroelectric power project. Later that year in September 2008, then-President Correa expelled their contractor, Odebrecht after international exposure of bribery and corruption. The termination of this contract saw a loss of 13 million USD. In 2010, Ecuador's CELEC signed an agreement to finance the project with Russia's Export-Import Bank (Roseximbank). The building was contracted to China's CWE for civil construction (contract amount was 240 million USD) and Russia's Inter RAO UES for electromechanical equipment. In response to construction delays, in February 2015 Ecuador's President Correa fined CWE 3.25 million USD. In December 2016, Correa once again called for the termination of the contract and in doing so, lost 3.6 million USD of public funds. Furthermore, the arrest of Alecksey Mosquera in April 2016, former minister of electricity under Rafael Correa's administration, was made after he allegedly accepted advance payment bribes amounting to nearly 1 million USD from Odebrecht for the construction of the dam. Correa has claimed it was just a business agreement.

In June 2016, a report by the State Comptroller's Office concluded that CWE violated and breached their contract, regarding the construction of the extensive tunnel system for the project. CWE did not carry out and comply with the "designs, plans, and technical specifications." The report also discussed the fact that the contractor, CWE, did not have "a soil and concrete laboratory, which allows for quality control of the concrete incorporated into the project." Local electricity officials requested the removal of the CWE superintendent of the project due to violations of basic labor rights found in CWE's mistreatment of workers. While both Chinese and Russian SOEs were involved with this stage of Toachi Pilaton, it is CWE's failings that resulted in the contract termination.

In 2019, a new contract was signed with a Russian Company, Tyazhmash, to complete the Toachi Pilaton Project. Despite more recent delays caused by the Ecuadorian government's COVID-19 regulations, which prohibited foreign personnel from entering the country and inhibited local companies from fully operating, 86.90% of the project was completed as of July 2020. While expected to be completed in the latter half of 2021, satellite imagery shows evidence of recent plant growth on the project, indicating construction delays and a lack of progress on parts of the site. However, imagery from 2019 and 2020 shows ongoing construction for the Pilaton intake dam and the Allurquin substation. The Toachi Pilaton project is anticipated to produce 254 MW of electricity between the 2 HPPs, Sarapullo (50.4 MW) and Alluriquin (204 MW). Construction created 2,075 jobs and will benefit 471,000 inhabitants. Like many Chinese-backed projects in Ecuador, the Toachi Pilaton project is accompanied by numerous social development projects such as improving potable water systems, expanding electricity networks, improving local infrastructure, and boosting local health facilities. The construction of the HPP is said to not have displaced any indigenous or vulnerable groups.

Mazar-Dudas and Quijos

As discussed previously, both Mazar-Dudas and Quijos were funded by CDB and constructed by CNEEC. For both projects, CELEC terminated the CNEEC contract in December 2015 due to non-compliance. Construction has not occurred at either of the HPP project sites since 2015, supported by both satellite imagery and Ecuadorian government data from May 2020 and March 2021 respectively. Government data claims Mazar-Dudas is 87.33% complete and Quijos 46.72% complete. Media coverage shows that Quijos specifically has virtually been abandoned. In May 2020, the Ecuadorian government announced that the Mazar-Dudas project would be completed by 2021, but there is no evidence observed on satellite images of construction restarting. For instance, no trucks or other equipment necessary to finish constructing the project have been observed. For the Quijos HPP project, there is no announced plan for the completion of construction, and there is recent plant growth at the construction site in December 2020 indicating a lack of construction, but stakeholders are supposedly discussing remedies.

For the Mazar-Dudas HPP project, construction was initially halted due to legal disputes between CNEEC and CELEC. The contract termination for non-compliance is from construction cost overruns and local conditions at the site. The project is now estimated to cost 83 million USD, a 66% expected price increase, a significantly higher amount than the initial 41.6 million USD loan from CDB. During the construction, three Ecuadorian laborers died in an accident, where the workers were suspended by 80-meter-long ropes while drilling into the mountain when the rock collapsed. Similar to other BRI projects in Ecuador, Mazar-Dudas is accompanied by community development initiatives; however, there is no evidence that these projects have occurred, and they may have been halted by the sudden contract termination.

For Quijos HPP project, CELEC found that CNEEC was not capable of maintaining technical quality and engineering standards due to numerous factors, including the firm's use of discontinued excavation methods, limited personnel, and lack of overall technical knowledge. This contract termination was supported by Ecuador's Public Procurement Service (SERCOP), which is, as of 2020, in mediation talks with CNEEC.

Conclusion

In 2007, Ecuador's then-President Rafael Correa made hydroelectric power a focus of his presidential campaign. This campaign promise would eventually take form as the resurrected Coca Codo Sinclair project, "a centerpiece of his administration's energy plan." With Chinese investors' support, eight hydroelectric power projects and/or dams were started, bringing Ecuador one step closer to generating enough energy to power the domestic grid as well as export regionally. It is important to note, while five of these projects have been completed, all "have missed deadlines due engineering and environmental problems." Similarly, in 2009, Bolivia's then-President Evo Morales debuted the "2025 Patriotic Agenda," which dictated Bolivia's goal of becoming the "energy heart of Latin America" and began the push for hydroelectric power in Bolivia. Both administrations welcomed the Belt and Road Initiative's infrastructure projects as a means to accomplishing their domestic energy development goals.

In Ecuador, Correa's promise to invest in hydroelectric power and transform the domestic energy grid drove his administration to work closely with Chinese SOEs. This push, in some cases, came at the expense of the local environment, impacting biodiversity on land, water, and consequently impacting livelihoods. However, these projects, as shown by the analysis in our scorecard, are overall less destructive towards the environment in comparison to Chinese-financed HPPs in Bolivia. There are still negative impacts, including Coca Codo's devastating oil spill and re-routing of the Coca River, but as a whole, there are fewer Chinese HPPs and/or dams in Ecuador located in protected areas, fully disrupting river flow, and leading to deforestation.

As a result of the environmental impacts associated with hydroelectric power projects and/or dams, communities can be disrupted due to forced relocation and changes in river patterns. For example, in Ecuador, three of the projects displaced communities. Shifting to the positive, five of the projects were coupled with substantial community development initiatives that ensured local communities benefited from the projects in some way. These initiatives were mandated and implemented by Ecuador's CELEC. This stands in stark contrast to Bolivia, where no social development programs accompanied the BRI projects.

Part of the gap between countries is attributable to the different approaches of their federal governments. Ecuador's federally-based strategy resulted in a more cohesive development strategy with additional oversight of projects, most visible in the contract terminations at Mazar-Dudas and Quijos sites when the projects were not up to Ecuadorian standards. In comparison, while Morales' Patriotic Agenda was outlined at a federal level, the domestic political turmoil in 2019 and 2020, eroded federal oversight and created a condition where local administration and interaction filled the vacuum. This shift is visible in the grassroots campaigns that successfully delayed multiple Bolivian HPPs. However, not all federal attention is positive: the intensive Ecuadorian federal interactions within the BRI projects set the grounds for corruption in Correa's administration.

Since October 2020, new administrations have gained power in both Bolivia and Ecuador. The agendas of both administrations are not set in stone and both have the power to forgo HPPs in favor of a more sustainable renewable energy infrastructure and create a foreign policy less dependent on China. It is unclear what the United States' role will be in the quickly changing geopolitics and domestic politics in Latin America. However, at least in Ecuador, the United States has the opportunity to reinvigorate this diplomatic and economic relationship by building on the grant given in January 2021 and working with the new Lasso administration.

Timeline

Dec 31, 2021

Mazar-Dudas' new expected completion date

Dec 31, 2021

Toachi Pilaton new expected completion date

May 24, 2021

Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso inaugurated

Mar 01, 2021

Ecuador reported no construction progress since December 2015 for Quijos

According to Ecuadorian government data and confirmed by satellite imagery.Jun 01, 2020

CELEC gains ownerships of Minas San Francisco

May 01, 2020

Ecuador reported no construction progress since December 2015 for Mazar-Dudas

According to Ecuadorian government data and confirmed by satellite imagery.May 01, 2020

Delsitanisagua briefly halted operation due to sediment accumulation

Apr 07, 2020

Coca Codo Sinclair oil spill

Source(s): El País, The ‘triple pandemic’ devastating Ecuador’s Amazon communities after an oil spill,

Apr 07, 2020

Ecuadorian Former President Rafael Correa convicted of corruption

Feb 29, 2020

First case of COVID-19 reported in Ecuador

Oct 03, 2019

Ecuador mass protests

The most recent mass protests in Ecuador, indigenous led protests against changes in fuel prices that resulted in violenceJan 01, 2019

Minas San Francisco became operational

Jan 01, 2019

Toachi Pilaton contracted for the third time

Dec 13, 2018

Ecuador signs a MoU to formally join the BRI

Dec 01, 2018

Delsitanisagua plant inaugurated

Dec 13, 2017

Former Ecuadorian Vice President Jorge Glas Espinel convicted for taking bribes

May 24, 2017

Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno inaugurated

May 01, 2017

China began to promote a more sustainable and environmentally friendly BRI

Dec 01, 2016

Toachi Pilaton contract cancelled for the 2nd time

Source(s): CPCCS, 3.6 millones de dólares mensuales ha dejado de percibir el Estado en proyecto Toachi-Pilatón,

Nov 01, 2016

Coca Codo Sinclair fails power test

Source(s): New York Times, It Doesn’t Matter if Ecuador Can Afford This Dam. China Still Gets Paid.,

Aug 01, 2016

Sopladora plant inaugurated

Apr 21, 2016

Former Electricity Minister Alecksey Mosquera arrested for taking a bribe

Jan 01, 2016

Quijos initially expected completion date

Dec 01, 2015

CELEC terminated CNEEC's contracts for Mazar-Dudas and Quijos

Source(s): Building Development for a New Era,

Apr 01, 2015

Alazan HPP, part of Mazar-Dudas, connected to Ecuador's energy grid

Dec 01, 2014

Coca Codo tunnel collapse kills 13 and injures 12

Jan 01, 2012

Minas San Francisco construction began

Jan 01, 2012

Mazar-Dudas construction began

Jan 01, 2012

Quijos construction began

Jan 01, 2011

Delsitanisagua contract signed

Jan 01, 2011

Sopladora contract signed

Jan 01, 2010

Coca Codo construction begins

Jan 01, 2010

CELEC signs contract with Roseximbank, CWE, and Inter RAO for Toachi Pilaton

Source(s): CELEC, Toachi Pilaton,

Sep 01, 2008

Odebrecht's contract for Toachi Pilaton cancelled

Jan 01, 2008

Ecuador defaults on international bonds

Feb 19, 2007

Ecuadorian Ministry of Energy and Non-Renewable Energy created

Jan 01, 2007

President Rafael Correa makes hydroelectric power a focus of his presidency

Jan 01, 1980

China and Ecuador established diplomatic relations

Jan 01, 1976

Coca Codo Sinclair initially proposed

Graphs

Ecuador Hydropower Projects

| Activity Name | Location | Cost (USD) | Expected Energy Capacity (MW) | Start date of construction | Activity Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coca Codo Sinclair | Napo-Sucumbi Province, Coca River | 2.6 billion | 1500 | 2010 | Completed in 11/2016 |

| Mazar-Dudas | Canar Province, Pindilig and Mazar Rivers | 41.6 million | 21 | 03/2011 | Under construction, delayed |

| Quijos | Napo Province, Quijos and Papallacta Rivers | 94.7 million | 50 | 01/2012 | Under construction, delayed |

| Toachi-Pilaton | Pichincha Province, Toachi and Pilaton Rivers | 240 million | 254 | 2008 | Under construction, delayed |

| Sopladora | Azuay Province, Paute River | 571 million | 487 | 04/2011 | Completed in 08/2016 |

| Minas San Francisco | Azuay Province, Jubones River | 312.4 million | 270 | 12/2011 | Completed in 01/2019 |

| Delsitanisagua | Zamora Chinchipe Province, Zamora River | 335 million | 180 | 12/2011 | Completed in 12/2018 |

| Canar and Naranjal | Canar Province, Canar and Naranjal Rivers | 289.9 million | N/A | 07/2013 | Completed in 01/2016 |

Source: Original work by W&M geoLab

Chinese Partner Information for Ecuadorian Projects

| Activity Name | Funder(s) | Funding Partner(s) Information | Implementer(s) | Implementing Partner(s) Information | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coca Codo Sinclair | Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) | A Chinese state-funded and state-owned policy bank | Sinohydro | A Chinese state-owned hydropower engineering and construction company, a subsidiary of PowerChina (which is under control of China's State Council) | |

| Mazar-Dudas | China Development Bank (CDB) | The bank is under the direct leadership of China's State Council | China National Electric Engineering Company (CNEEC) | A Chinese state-owned engineering company | |

| Quijos | China Development Bank (CDB) | The bank is under the direct leadership of China's State Council | China National Electric Engineering Company (CNEEC) | A Chinese state-owned engineering company | Overseen by CELEC, a state-owned Ecuadorian company overseen by the Ministerio Energia y Recursos Naturales No Renovables |

| Toachi Pilaton | Ecuador's BIESS Bank and Russia's Export-Import Bank | Both banks are state-owned by their respective countries | China International Water and Electric (CWE), Brazilian conglomerate Odebrecht, and the private Russian companies Inter RAO UES and Tyzahmash S.A. | CWE is a subsidiary company of the Chinese state-owned Three Gorges Corporation | Overseen by CELEC, a state-owned Ecuadorian company overseen by the Ministerio Energia y Recursos Naturales No Renovables |

| Sopladora | Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) | A Chinese state-funded and state-owned policy bank | China Gezhouba Group Corporation (CGGC) and the private Ecuadorian company Fopeca | A subsidiary of China Energy Engineering Company (CEEC), which is under direct control of China's State Council | Overseen by CELEC, a state-owned Ecuadorian company overseen by the Ministerio Energia y Recursos Naturales No Renovables |

| Minas San Francisco | Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) | A Chinese state-funded and state-owned policy bank | Harbin Electric | A private Chinese company | Overseen by CELEC, a state-owned Ecuadorian company overseen by the Ministerio Energia y Recursos Naturales No Renovables |

| Delsitanisagua | China Development Bank (CDB) | The bank is under the direct leadership of China's State Council | HydroChina | A Chinese state-owned hydropower engineering and construction company, a subsidiary of PowerChina (which is under control of China's state council) | |

| Canar and Naranjal | Bank of China (BOC) and Deutsche Bank (China) | A Chinese state-owned commercial bank and a Chinese branch of a private company | China International Water and Electric (CWE) and the Ecuadorian state-owned company Senagua | CWE is a subsidiary company of the Chinese state-owned Three Gorges Corporation |

Source: Original work by W&M geoLab

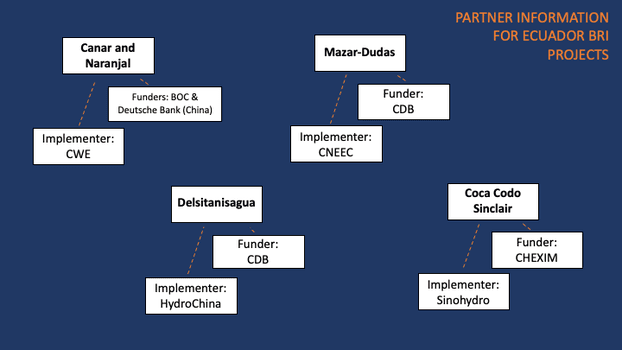

Visual of Funders and Builders Part 1

Visualization of the above table. All projects in this visualization were both financed and built by Chinese enterprises.

Source: Original work by W&M geoLab

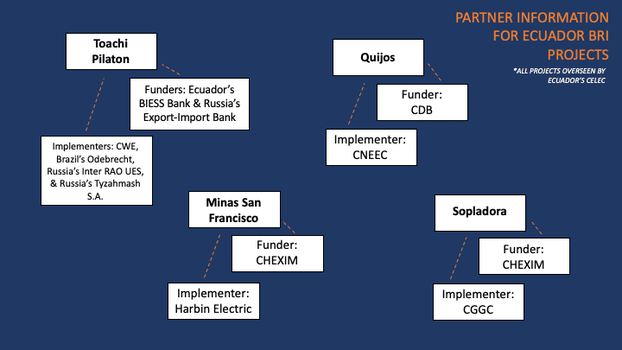

Visual of Funders and Builders Part 2

Visualization of the above table. Almost all projects in this visualization were both financed and built by Chinese enterprises, and supervised by the Ecuadorian government (CELEC). The only exception is Toachi Pilaton, which was funded by Russia (Russia's Export-Import Bank, Roseximbank). One of the major builders for Toachi Pilaton is China International Water and Electric Corp (CWE).

Source: Original work by W&M geoLab

Scorecard for Ecuador BRI Projects

| Activity Name | Environment Average Score | Community Impact Average Score | Legal Issues Average Score | Total Average Score | Ranking based on final score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coca Codo Sinclair | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.68 | Unsuccessful |

| Mazar-Dudas | 1.00 | 1.33 | 0.88 | 1.07 | Neutral |

| Quijos | 0.50 | 1.67 | 0.75 | 0.97 | Neutral |

| Toachi Pilaton | 1.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | Neutral |

| Sopladora | 2.00 | 1.33 | 1.25 | 1.53 | Successful |

| Minas San Francisco | 2.00 | 1.75 | 1.25 | 1.67 | Successful |

| Delsitanisagua | 2.00 | 1.67 | 1.25 | 1.64 | Successful |

| Canar & Naranjal | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.25 | 1.75 | Successful |

In this article, and the previously released case study on hydropower in Bolivia, each BRI project was analyzed in the context of environment, community impact, and legal indicators. These three indicators were then broken down into relevant success factors. For each success factor, each project was ranked as unsuccessful (0), neutral (1), or successful (2). To rate the overall impact of the dams, the scores for each dam were averaged out, creating a scaled ranking of unsuccessful (0 - 0.68), neutral (0.69 - 1.34), and successful (1.35 - 2). For convenience the average score for each category and the overall ranking is shown in this table. For more information on the specific rankings for each project and success factor, see the whole scorecard of hydro project factors.

Source: Original work by W&M geoLab

Look Ahead

Please download the structured data in the Data Sources section. Data sources include a spreadsheet of 160+ BRI projects and mappable KMZs and Shapefiles of projects throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. For more analysis of our data, please read geoLab's other three Tearline articles, including the complementary case study of hydropower in Bolivia.

Things to Watch

- Whether construction on the three unfinished projects will accelerate as COVID-19 alleviates and anti-corruption campaigns are enacted in Ecuador?

- If the size and quantity of cracks in the Coca Codo Sinclair dam increases?

- If the new Lasso administration will change Ecuador's foreign policy with the United States and China?