Overview

This study defines and parses the differences between territorial / separatist terrorism versus non-territorial seeking terrorism from a spatial and geographic perspective. This spatial/geographic component of the research is foundational due to prior research often focusing on the motivations of terrorism rather than spatial and geographic perspectives.

Activity

The complexity of terrorist target selection is often minimal. The inferential interpretation of previous research can often predict the vulnerability of target areas. For example, non-territorial terrorists often target the same types of areas. However, this study shows that territorial terrorists (separatists) are more difficult to predict. They often operate in peripheral environments within geopolitical conflicts. This study found the coefficient of the standard deviation of nighttime lights per 5-km grid cell (showing electrification) to be strongly and negatively correlated with the presence of terrorist attacks, suggesting as an area becomes more scattered with lights (diverse) the less likely non-territorial terrorists will attack. Drawn out further for future study, what does this mean for separatist terrorism?

Introduction

A 2013 meta-analysis of counter-terrorism studies noted the majority of research focuses on political and sociological perspectives with little focus on geographic ones. However, if government policies are designated within a defined territory, terrorism can, in some part, be understood as an attempt to influence control over political boundaries. Similarly, strong links between a lack of territorial security and the presence of terrorism have been found as a lack of governmental control enables terrorists to view the environment as permissive to their acquisition of an autonomous zone.

Further, high population areas and those of governmental importance are both attractive and cost-effective targets while cities of high regard increase their appeal. A terrorist's specific motivations also have a geographic component, exemplified by religious groups targeting places of worship; right-wing terrorists selecting governmental buildings; persecuted individuals seeking out civilians in everyday locations; and territorial terrorists operating in peripheral environments. There is even a self-reinforcing cycle in which areas previously attacked become increasingly attractive to future attackers and a relationship between the terrorist base of planning and preparation suggests target locations are a function of geographic convenience as much as an act of coercion.

In efforts to predict terrorism, a number of methods have been employed including Hidden Markov Chains, feed-forward Neural Networks (NN), ensemble models, and Support Vector Machines (SVM). These models have been applied to identifying deceptive behavior, predicting attributes of terrorism, and even the region in which terrorism is likely to occur with results ranging from 60 to 95% accuracy.

However, while such previous work has reported robust results, few studies have focused specifically on remote sensing and spatial sciences. While one author included nighttime lights and digital elevation models in their research, it is still not well understood how these variables contributed to the results or the spatial accuracy.

This research aims to predict terrorism in Europe at the sub-national level. Objectives of the research are: (1) develop a model to predict terrorism using satellite imagery and socio-environmental data and (2) develop a grid-cell-based spatial statistics approach to reveal specific causal variables and trends in this region at a previously unexplored spatial scale.

Methods

This study includes 18,741 attacks occurring between 1970 and 2018 in Eastern and Western Europe apart from Russia. The target feature was developed from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Global Terrorism Database (GTD). The GTD is an open-source data set of terrorist incidents since 1970 that has been geo-referenced, matches the definitional criteria of the study, and has been the primary source of terrorism studies in the United States.

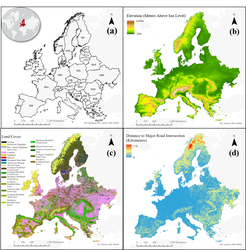

Remotely sensed data was collected from a variety of sources including the 2000 Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, 2020 Copernicus land cover, and 2018 nighttime lights from the Visible and Infrared Imaging Suite (VIIRS) sensor on board the Joint Polar-orbiting Satellite System.

Geospatial and population features were collected from WorldPop, a peer-reviewed research data archive. From this archive, data was obtained on distances to major waterways, inland water, major road intersections, roadways, population counts, population densities, built settlement growth, and demographics from 2000 to 2020.

Civil unrest was calculated from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data set (ACLED). It should be noted as a limitation, however, that this study covers terrorism until 2018 (the last year GTD has data available at the time of the study) while civil unrest is calculated from data beginning in 2018, the earliest year ACLED has data available at the time of the study. It is therefore assumed this feature is representative of larger civil unrest during the study's time period.

For spatial-temporal analysis, the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS), which documents sociopolitical interactions extracted via open-source documents, is used.

Shapefile boundaries were imported from the Department of State International Boundaries data source and ACLED data was imported as vector points before being converted to raster format at a 10 km ground sampling distance (GSD). Pixel values were calculated as the number of events occurring within the GSD. Next, 5 square kilometer hexagonal cells were created within the area of study and vector points placed at the centroid of each polygon. Points falling within a 3-km buffer of attack locations were removed. The spatial resolution for each observation is therefore approximately 5-km.

The 23 Copernicus land cover classifications were aggregated into urban, vegetation, agriculture, and water. The data was then split into training (0.7), evaluation (0.15), and hold-out test splits (0.15). Evaluation data was used for comparison and hyper-parameter tuning while the hold-out test set was used only for final performance assessments.

An unpruned Random Forest of 100 trees was fit to the training data and permutation importance used to retrieve feature importance scores from the evaluation set to understand each feature's generalization. This methodology performs robustly on random values, datasets containing both categorical and binary features, as well as in the presence of collinearity.

Features with lower feature importance and correlation coefficients higher than 0.7 were removed apart from binary and categorical features and data was normalized to a 0 - 1 scale resulting in the following features used for prediction: (1) distance to inland waterway, (2) distance to major road, (3) distance to major waterway, (4) elevation, (5) civil unrest, (6) population density, (7) slope, (8) nighttime lights, as well as (9) urban and (10) agricultural land-cover.

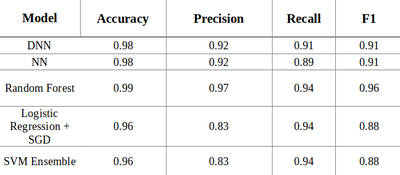

Five machine learning algorithms were trained and evaluated for comparison as each maintains specific strengths and weaknesses specific to this study. Logistic regression's ability to map probabilities, robustness to skewed distributions, and intuitive coefficient interpretation, has proven itself in the face of more complex tools such as Support Vector Machines and Neural Networks. This model was optimized with stochastic gradient descent, leveraging an alpha value of 1 x 10-6 and an initial learning rate of 0.1 producing an 87% F-1 score.

By aggregating the predictions of multiple weak decision trees, the Random Forest classifier is likely to be an ideal model for this topic as it has found success among co-linear features, is largely unresponsive to over fitting, and provides impressive performance in handling categorical and continuous variables, unbalanced data, and outliers, all of which are present. This model leveraged a max depth of 3 trees, Gini impurity, and considered a maximum of 3 features for each split resulting in an F-1 of 96%.

Support Vector Machines (SVM), which are well known for the kernel trick, delineate non-linearly separable data by mapping data points into an n-dimensional kernel to avoid the computational costs of calculating n dot products in a 3-D feature space. The primary parameters of the Radial Basis Function kernel, gamma and C, were sampled from logarithmic grids. However, despite the kernel tricks' success, SVMs are computationally expensive as fit times increase at a quadratic rate with the number of observations. As a result, ten SVMs were trained in a bagged ensemble. Each child estimator was exposed to a random sample of 0.1 of the training data set without replacement, decreasing fit times while improving generalization. This model, leveraged a C and gamma of 1.0 and .0069, resulting in an 87% F-1.

Neural networks comprise an arbitrary number of layers connected by an arbitrary number of neurons allowing them to learn non-linear decision boundaries via activation functions. The size of the model, both in terms of width and depth, impacts the level of complexity that can be learned. However, larger models often degrade in performance past a consistent depth due to the number of matrix computations. Therefore, it cannot be stated that a deeper or larger model will necessarily perform better, only that with proper techniques to avoid vanishing gradients and over fitting, it will not likely perform significantly worse.

The shallow NN obtained from Uddin et al. 2020 consisted of a single hidden layer of 10 neurons with an initial learning rate of 0.001, 500 epochs of training, Adam optimization, logistic activation function, and cross-entropy loss. The DNN leveraged the same hyper parameters as the single layer NN but with 5 layers consisting of 100, 50, 30, 10, and 5 neurons. The neural networks achieved a 0.91 and 0.92 F-1 score respectively.

Results

Table 1 compares the results across accuracy, average precision computed from precision-recall curves, and F-1 scores. Average precision and F-1 were chosen as the evaluation metrics due to their robustness in the face of large class imbalances. Each model performed exceptionally well but the Random Forest outperformed every other across all tasks.

Spatial statistics were then used to validate the Random Forest's spatial accuracy. Join counts were used to assess the spatial correlation between the classifier's predictions. We can understand spatial processes and distributions as one of many, or potentially infinite, possibilities. Therefore, by modeling random distributions, join counts compare synthetic results with ground truth to assess the likelihood of geographic correlation among predictions.

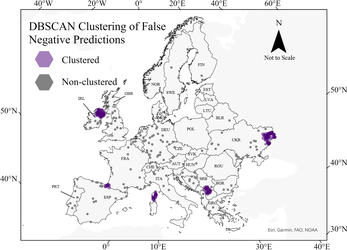

With a synthetic p-value of 0.191, the Random Forest did not demonstrate a statistically significant correlation among incorrect predictions at large. With a high simulated p-value, this research can reject the null hypothesis that the results were clustered, and thus, spatial correlation is not occurring among incorrect predictions at large. However, the model did exhibit significant spatial correlation in terms of false-negative predictions with a synthetic p-value of 0.001.

Further analyzing terrorism's spatial relationship, a Poisson regression found the coefficient of the standard deviation of nighttime lights per grid cell to be negatively correlated with the presence of terrorism (98% significance), suggesting the similarity of an area's economic development and population density may be a driving factor in target selection. Nonetheless, a lack of statistically significant spatial-temporal correlation between geo-referenced sociopolitical publications and attack locations suggests more research should be done to parse when attacks are likely to occur where they do.

Finally, a DBSCAN model identified clusters of false negatives in the Donetsk region of Ukraine, Northern Ireland, Kosovo, the Basque country of Spain, and the island of Corsica, France.

Discussion

Although the best performing model, Random Forest, predicted false-negative clusters, it revealed an underlying trend: each cluster is a hot spot of terrorism in which territorial control was the primary grievance or objective. As noted earlier, Northern Ireland saw increased levels of ethno-nationalist conflict from the 1960s to late 1990s; the Basque area of Spain also saw armed conflict from the 1960s to early 2000s between Basque organizations who sought independence; Kosovo, underwent a massive upheaval with respect to autonomy in the 1990s between Yugoslavia and Kosovo nationalists; Corsican nationalists have fought French, Italian, and Spanish security forces regarding independence from France. Most recently, conflict in the Donetsk region of Ukraine stemming from the 2014 Russian invasion has resulted in Russian separatists fighting for annexation into Russia.

While non-territorial terrorists target highly populated urban areas with symbols of their grievance, separatism is a function of operating on the periphery where the current government does not retain high degrees of control. These locations are likely to occur outside of the most populated areas that are typical of other types of terrorism. This likely explains the clustering but highlights the geographic differences between these types of terrorism. Further, the lack of clustering among non-territorial terrorism suggests sub-classes of terrorists (right-wing, left-wing, environmental, etc.), maintain similar geographical logic and planning. Thus, it may be more appropriate for future studies to examine terrorism in terms of its territorial or non-territorial nature rather than the specific issues that drive them.

These findings can play an important role in counter-terrorism analysis. First, given Random Forest's outperformance of more complex models, it can be inferred that the complexity of terrorists' target selection is not high as it can be deduced from an ensemble of decision trees. In fact, these results indicate that areas analysts often believe to be likely targets based on the common intuition and established literature are, in fact, the most likely targets. Additionally, no significant spatial-temporal relationship between ICEWS and GTD data was found, suggesting that terrorists are not likely to be mobilized by the larger sociopolitical discourse. It can be inferred that terrorists are either uninterested in public conversation or are largely disassociated from it. If the former is true, terrorism may be a marketing campaign of sorts, aimed at moving the direction of conversation towards an area of their favor. If the latter holds, then more research should be done to collect the interactions terrorists are interested in.

Despite these findings, challenges to data collection and limitations to this research still remain. First, a 25 sq. km hexagonal grid cell approach was used. However, this approach could not take into consideration neighboring pixel values in the rasters from which the features were drawn. It may be deduced that if an attack occurred in an area deemed agricultural, but on the edge of the pixel nearest urban areas, the attack location was not chosen due to its agricultural nature but its proximity to urban centers. Attempts to include this spatial attribute using interpolation methods degraded model performances.

To ensure this limitation was not detrimental, multiple experiments were conducted at different grid-cell sizes (100 and 50 square kilometers), shapes (square), and random sampling. Across all experiments, results differed marginally. The method proposed in this study produced the highest results, though relative model performance remained consistent across all experiments with Random Forest outperforming every other model.

Additional Caveats

Despite this study's strong findings, readers should understand the limitations of results derived from a systematic point sampling. There are many areas in Europe that are quite obviously not at risk of being attacked (such as rural areas), and few would suggest that they are vulnerable now or in the near future. These unlikely areas (mostly rural and peripheral) were identified by the model potentially inflating the 99% accuracy reported as compared to isolating more challenging areas (rural and separatist attack characteristics) at finer resolutions. The systematic sampling was chosen to eliminate the possibility of selection and/or sampling bias, but readers should nonetheless be aware of such shortcomings. Future research may improve upon this by introducing deep learning techniques such as key point detection, applying kernels to the entirety of an area, but isolating the specific attack location. This approach would have the added benefit of considering the spatial relationship of nearby pixels in predictions.

The features collected for this data contained only a snapshot of the time period covered. For example, it is not believed a terrorist attack in 1970 could have foreseen the land use of Europe in 2020, and it is unlikely the classification would have remained across the fifty years. Greater control over the spatial-temporal aspect of terrorism should be a consideration of future research.

From this work, we can conclude the following: Terrorist target selection is not complex and can largely be inferred. Additionally, non-separatist terrorism operates with like-spatial logic but is distinct from that of separatists. Parsing the spatial dimension of territorial terrorism will likely require a unique set of explanatory variables and model selection that is not captured here. Lastly, this study has found the coefficient of variation of nighttime lights to have strong impacts on the level of terrorism, a unique finding not previously determined in past literature.

Graphs

Visual Summary

Major finding: separatist terrorists operate with diverging spatial logic compared to their non-separatist counterparts. However, no matter the subtype of non-separatists (left/right-wing, environmental, etc.), they all appear to operate with similar spatial logic.

Feature Importance

Feature importance scores from the best performing model indicate non-territorial terrorists target economically well-developed, urban areas near major road intersections. These findings are precisely inline with established literature, providing researchers with the confidence the model is making sound predictions.

Source: original work

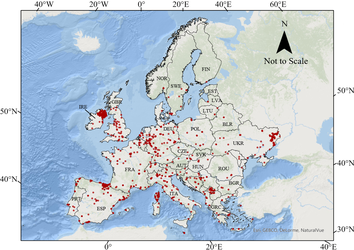

New Predicted Attack Locations

These 5-km grids (enlarged for visualization) represent grids the model has predicted at-risk based on previous attacks.

Source: original work

Look Ahead

The results from this study suggest the spatial dispersion of terrorism in Europe today will likely hold for the foreseeable future, with geopolitical conflicts stemming from separatist sentiments being the most likely cause for disrupting the status quo. Therefore, such movements should be watched closely. To date, the growing body of successful literature on applying machine learning techniques to the prediction of terrorism suggests the application of such models in real-world settings has a promising outlook. However, more work should be done to validate the empirical results reported thus far with respect to practical applicability, especially separatist terrorism.

Things to Watch

- Could Convolutional Neural Networks and Keypoint Detection techniques provide better predictive capabilities at finer resolutions?

- What alternative variables could be used to assess the temporal risk of terrorism outside of those used in this study?

- A follow-up report focusing on the more challenging areas of separatist terrorism.