Overview

We develop and apply a process for identifying the deliberate targeting of building types during ongoing armed conflict by conflict actors. Results indicate that cultural, and secondarily medical, buildings are likely to have been deliberately targeted by combatants. Targeting, however, occurred only in cities where direct fighting (territorial contestation) between Russia and Ukraine was ongoing.

The process combines remote collection of high-quality data through satellite imagery and automated AI-detection of building damage with statistical methods to rule out explanations other than deliberate targeting and provide insight on the reasons for deliberate targeting. We provide an explanation for deliberate targeting consistent with available evidence: combatants targeted buildings that supported the will and/or ability of their opponents to sustain combat operations.

Activity

Does Russia deliberately target some types of buildings--including civilian buildings--over other? What influences Russia's building targeting decisions. Based on statistical analysis of AI-developed data, we find that among Cultural, Educational, Medical, Religious, and Other building types, Russia targets Cultural and to a lesser extent Medical buildings at a higher rate than other building types. The higher rate of damage, which we refer to as "disproportionate damage," occurs even after we control for common explanations for why a building is damaged such as size, proximity to other damaged buildings, location in Ukraine, etc. As a result, disproportionate damage is likely the result of a deliberate attempt by combatants--primarily Russia--to damage a building or to use military activity that is known to cause damage to a building. Deliberate damage occurs only in areas and at times where active contestation between Russian and Ukrainian military units is occurring. This suggests that disproportionate damage occurs because Cultural and Medical buildings play a role in local fighting. Roles may include improved defensive positions, observation locations, or treatment of wounded soldiers.

Introduction

Just as surely as it leads to loss of life, war also destroys property. Many of the most harrowing images of war depict the loss of shelter, historical buildings, and critical services. While war destroys, it does not do so equally. Even within the same city or battlefield, some buildings experience damage while others do not. Which building types are more likely to suffer damage? Is targeting deliberate? Why does this damage occur? This paper proposes a process that combines AI-driven data collection and quantitative causal analysis to answer these questions. Results provide an improved understanding of where, when, and, most importantly, why building types are deliberately targeted by combatants during ongoing armed conflict. The results provide insights about, but are not designed to identify, who caused damage. Findings contribute to our understanding of armed conflict, including a better understanding of local combatant goals and strategies and the civilian consequences of war. Findings also have policy implications such as an improved ability to forecast the consequences of fighting and identification of deliberate government policies by participating combatants that may constitute war crimes.

This process is applied to the case of Donetsk Oblast during the first year of conventional fighting following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine (24 February 2022 to 23 February 2023). The requisite spatially and temporally disaggregated dataset is developed. Additional data on building type, building characteristics, and proximity to other relevant targets are included to allow the statistical methods to assess competing explanations for damage. Damage is also analyzed across contested and uncontested cities to provide insight on why damage occurred. Based on this data and analysis, we find that cultural buildings (heritage centers, libraries/archives, memorials, museums, and performance centers) are 68% more likely to suffer damage than other building types in Donetsk Oblast (including medical, educational, religious, and other buildings). The higher rate of damage to cultural buildings occurs only in locations that are actively contested by Russia’s and Ukraine’s armed forces as evidenced by either ongoing fighting or incomplete territorial control by a single combatant over a week. Medical buildings are also 13% more likely to suffer damage than other building types in contested locations.

Based on the evidence, we argue that cultural and medical buildings were likely targeted by combatants because of their perceived role in helping an opposing force sustain military operations in a specific location. This tactical explanation emphasizes the use of coercion to influence local decisions by an opponent to continue or abandon a specific fight as opposed to decision-making over the type of strategy used in the war itself.In general, punishment strategies are seen as less effective when stakes are higher. As a result, use of such a strategy more plausibly leads to limited tactical gains. See, for example, Abrahms, M. (2006). “Why terrorism does not work,” International Security 31(2): pp. 42–78.[1] We reach this conclusion about the causes of deliberate targeting based on the type of buildings observed to be damaged, our ability to rule out many alternative explanations for targeting, and the conditions under which targeting occurred.

Cultural buildings are more likely to have stone or reinforced concrete construction that makes them more suitable as fighting positions, command posts, or civilian shelters. Medical buildings provide critical care that helps trapped civilians and military forces alike. The specific rationale for targeting these building types differ by perpetrator. Both Russia and Ukraine benefit from targeting buildings that their opponent uses to sustain military operations, such as reinforced buildings and medical facilities. Russia additionally benefits militarily from targeting buildings that support civilians. Ukraine’s will to fight in a location may partially depend on the protection of remaining civilians. By destroying key buildings that serve civilian needs, civilians are forced to exit, which undermines a key rationale for continued Ukrainian defense. Our data and analysis do not allow us to identify the perpetrator of building damage. During the period of study, however, more battles involved Russia’s forces trying to defeat well-entrenched Ukrainian forces in slow, grinding battles where Ukrainian civilians were present. As a result, observed deliberate targeting is more likely to have been perpetrated by Russian as opposed to Ukrainian forces.

The process proposed and the results developed using this process advance existing work—especially work that does not account for alternative explanations or only examines a subset of building types—in several important ways.For an example of prior work that does not use comprehensive data or statistical methods, see Khoshnood, K. et al. (2022). “Damage assessment of health and educational facilities in Sievierodonetsk raion, Ukraine: evidence of widespread, indiscriminate, and persistent bombardment by Russia and Russia-aligned forces between 24 February – 13 June 2022,” Yale School of Public Health, 24 June.[2] First, building damage is identified systematically and comprehensively using satellite imagery and machine learning. This allows near real-time identification of damage and provides information on all buildings (of a certain minimum size) that are damaged. A comprehensive and representative sample is critical for conducting scientific research across difficult-to-access environs such as conflict-affected countries and areas affected by natural disasters. Second, the process uses statistical methods to test and compare numerous existing explanations for the occurrence of targeting. This makes it possible to rule out explanations for the occurrence of damage other than deliberate targeting. Ruling out many alternative explanations for the occurrence of damage is required to identify deliberate targeting. Third, the process exploits spatial heterogeneity—including variation in the intensity of fighting and in which combatant has control over an area—to provide evidence of why damage was caused (the statistical methods additionally help to answer these questions).

The paper unfolds as follows. We first describe the process and the methodology. The application of this process to Donetsk Oblast is discussed next, including the data that is generated, the variables assembled, and the statistical analysis employed. Examples of satellite data are shown to illustrate the types of buildings we observe to be damaged. The results of our methodology are then presented and discussed. We identify which type of building our process finds to be deliberately targeted and why this targeting may have occurred. This section also addresses potential limitations of our method, which result primarily from the use of a data sample for a single oblast and the use of satellite imagery to detect damage, as well as scoping conditions. This discussion provides guidance on when it is appropriate to draw conclusions based on this analysis. The paper concludes with policy implications and next steps in the development of the methodology to identify and explain damage to civilian infrastructure.

Process to Identify Deliberate Targeting of Building Types

The proposed process is as follows. First, given a case of interest, polygonal building footprints are identified. Second, change detection based on satellite imagery is used to determine if the pixels in a building footprint have changed, which may indicate damage. Third, an AI model is built, trained, and validated to accurately identify when detected change corresponds to damage to a building structure. Fourth, variables that can be systematically collected on building characteristics—including type—are collected for each building in the sample. Fifth, variables that account for various spatial characteristics that might affect the occurrence of damage, such as building density and proximity to other damaged buildings, are constructed. Sixth, advanced statistical models that address temporal autocorrelation, the clustering of observed damage, and unobserved bias by time, city, and city time-trend are run. Seventh, results across areas on and behind the frontline and areas under the territorial control of each combatant are assessed to determine the conditions under which damage occurs and who the likely perpetrator of damage is.

The goal of the process is to determine if some types of buildings are more or less likely to be targeted deliberately by combatants during an armed conflict and to help explain why targeting occurs. We use large-N data and statistical methods to accomplish this goal for several reasons. Statistical analysis makes it possible to separate systematic explanations (e.g., proximity to main roads) from non-systematic or “idiosyncratic” explanations (e.g., targeting error by a pilot). A combatant policy of deliberate targeting is a systematic explanation for damage, but it is only one of several systematic reasons. Statistical analysis can further differentiate between competing systematic explanations for observed damage. For instance, it is possible to determine if a building is damaged due to its type or due to its proximity to main roads. Combatants often use main roads to travel or resupply their forces, which means that proximity can lead to collateral damage to buildings. With sufficient data, it is possible to reliably compare many explanations for the occurrence of damage. It is difficult, if not impossible, to assess competing systematic explanations using non-quantitative methods or very small sample sizes.

Measuring intentional combatant policy directly is difficult. For this reason, we utilize a systematic variable “building type.” This variable is a proxy for variation in building characteristics that may influence deliberate targeting such as building purpose, prominence, or construction materials. Buildings, on average, differ in these characteristics across each type. This makes it possible to use “type” to infer the local or strategic value of a building. Combined with statistical methods, it is possible to infer combatant policy from the observation that certain building types are damaged at a higher rate than others. To do this, it is necessary to collect data on all buildings (or at least a representative sample of buildings) to compare damage rates among building types.

The main impediment to understanding if buildings are targeted deliberately when using building “type” as the main variable is that there are many reasons why we might observe disproportionate damage to a building type unrelated to deliberate targeting. In other words, there are other variables correlated with both building type and building damage that explain the observed occurrence of damage. This is referred to as a “confounding variable.” For instance, cultural heritage buildings, which are one of the building types we examine, may be more likely to be located near to the center of a city. More intense fighting may also consistently occur near to a city’s center because combatants see value in controlling the center or the center is a contested “no man’s land” that sees continual bombardment. To continue the example above, proximity to a city’s center would explain why a certain type of building is more likely to be damaged, and this explanation would be unrelated to deliberate targeting. To give “building type” its intended causal interpretation of deliberate targeting it is necessary to account for all important confounding variables.A correlation between building type and damage absent steps to account for confounding variables would still indicate that there is a relationship. The reason for this relationship, however, may be unrelated to deliberate targeting.[3]

We take two steps to address the presence of confounding factors that may impede our ability to understand the relationship between building type and observed damage as deliberate targeting by a combatant. First, we utilize a statistical model that incorporates two-way fixed effects by location and time (by city and week in our application). Location fixed effects account for the impact of unobserved factors unique to the place where a building is located that do not vary over time, such as more intense fighting, strategic importance, or proximity to borders. Time fixed effects account for the impact of unobserved factors unique to a temporal period that do not vary by location, such as changes in military strategy or changes in support for a combatant. To further improve the robustness of the analysis, we also include location-specific linear time trends. These trends adjust for confounding factors unique to a location that have a directional change such as increasing or decreasing discrimination in the use of munitions in a location.

Second, we collect data on, and control for, several time-varying and building-specific explanations for damage other than building type. We do this because fixed effects do not account for alternative explanations that may vary by location and time. These variables include: (a) the size of the building footprint, (b) the distance of the building to the city centroid, (c) the distance of the building to the nearest primary road, (d) the distance of the building to the nearest secondary road, (d) the number of other buildings within 500 meters, (e) the lagged number of buildings of a different type damaged within 500 m, and (f) the lagged number of buildings of the same type damaged within 500 meters.The analysis is robust to the use of varying distances including 150 meters, 250 meters, and 500 meters. The models presented use the 500 meter distance. Distance variables are logged to account for the fact that close distances are likely to have a larger impact than far distances. The results, however, are robust to the use of other function forms, including square root, no transformation, and squared.[4] Each of these variables represents a reason why we may observe building damage during a war other than deliberate targeting by a combatant. Specifically, they capture an elevated chance of unintended “collateral damage.” Collateral damage may still result from combatant behavior. The intentional use of heavy weapons, for example, makes collateral damage far more likely, but its occurrence is different from intentional targeting.

Application to Donetsk Oblast in Ukraine

To show its utility, this process is applied to the case of Donetsk Oblast in Ukraine between 24 February 2022 and 23 February 2023. Donetsk Oblast, located in eastern Ukraine, has seen continuous fighting since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began on 24 February 2022. Mariupol was one of the first cities to suffer large-scale damage with nearly half of its buildings suffering damage after it was sieged by Russia’s armed forces and then eventually captured on 20 May 2022. Fighting continued throughout the period of study, with Lyman, Soledar, Vuhledar, and Bakhmut seeing particularly intense combat.Karklis, L., and Cunningham, E. (2022). “Three maps that explain Russia’s annexations and losses in Ukraine,” The Washington Post, 30 September. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/09/30/map-ukraine-regions-annexation-russia/; Kirby, P. (2022). “What Russian annexation means for Ukraine’s regions,” BBC News, 30 September. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63086767; Reuters. (2022). “Russia’s Federation Council ratifies annexation of four Ukrainian regions,” Reuters, 4 October. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-federation-council-ratifies-annexation-four-ukrainian-regions-2022-10-04/. Bachega, H., and Fitz-Gerald, J. (2023). “Ukraine war: Russian troops forced out of eastern town Lyman,” BBC News, 2 October. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63102220; Spike, J. (2022). “Ukrainian authorities take stock of ruins in liberated Lyman,” AP, 8 October. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-business-war-crimes-donetsk-59c7e2747b3bde5fdf78ca94aca8bf54; The Visual Journalism Team. (2023). “Ukraine war: Soledar devastation revealed in satellite images,” BBC News, 12 January. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-64250202; Meldrum, A. (2023). “Ukraine forces pull back from Donbas town after onslaught,” AP News, 25 January. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-politics-government-d1c0957d5dddd106dbb5eca7c6521e1a; Keaten, J. (2022). “Russia grinds on in eastern Ukraine; Bakhmut ‘destroyed’,” AP, 10 December. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-putin-zelenskyy-government-germany-74c2f2bb64bba8ff3bb93cd6d41b54da.[5] Dontesk Oblast is an appropriate test case for several reasons. High-quality satellite imagery and substantial data to account for alternative explanations are available, which allows implementation of all steps of the process described in Section 2, improving internal validity of the results. In addition, there is substantial variation in the intensity of fighting, the amount of attacks initiated by both sides, combatant territorial control, and the extent of building damage making it possible to understand the context under which building destruction occurred. Finally, fighting involved the use of weapons and techniques—small arms, artillery, missile strikes, and attrition warfare—common in other conflict settings. For this reason, results from this case are likely to be relevant for future, similar conflict situations, which improves the external validity of the results.

Statistical Method

Our unit of analysis is a building-week, which means that we provide an estimate of the probability that a type of building is damaged in a week. The data contains 61,543 buildings in 140 cities over the course of 51 weeks. Buildings are dropped from the sample once they are observed to be damaged. After taking these steps, the total number of observations is 2,964,234. Once fixed effects and lagged variables are included, the number of observations drops to 1,898,667. The dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether a building was observed to be damaged in a week. The independent variable is the type of building (cultural, educational, medical, religious, and other). Based on the unit of analysis and the independent variable, significant results indicate that a higher portion of one type of building is damaged compared to another type. See section 3.2 for a more detailed discussion of the data.

Quasibinomial statistical models are used because the dependent variable is binary (damage either does or does not occur to a building in a week). The advantage of the “quasi” version of a binomial model like a logit is that the standard errors account for possible overdispersion in the dependent variable that may occur if, for instance, there are many zeros. The analysis produces confidence intervals, which makes it possible to quantify confidence in relationships identified. Specifically, the confidence interval provides the range of values we might observe for the proportion of buildings of a particular type that are damaged 95% of the time if we were to repeatedly sample and analyze the data. Greater statistical significance (lower p-values) indicates greater confidence that the effect is consistent across samples and that a specific building type, after accounting for alternative explanations, suffers damage at a rate disproportionate to other building types.

Data

The dataset used in our analysis is derived from several data sources.

Building destruction: We use new data that records damage to all buildings in Donetsk Oblast that are greater than 370 square meters (4,000 square feet) and are within a city with a pre-invasion population greater than 2,000. This includes a total of 140 different cities. Damage is recorded daily. The determination of if a building is intact or significantly damaged leverages daily Planetscope (Planet 2022) imagery from a constellation of SmallSats.Planetscope imagery pixels included in the analysis were selected by points distributed across building footprints. These points were at least 5 meters from any building footprint ensuring imagery pixels did not capture an edge of the building. This process was automated through an ArcGIS Modelbuilder model. Results were spot-checked by analysts with no orthorectification issues observed.[6] The imagery has a 3.125 meter spatial resolution. As a result, only large-scale damage or destruction is detectable. A total of 5,088 buildings (8.3%) were observed to be damaged. This data is also used to record the number of buildings and the number of damaged buildings of the same and different type within varying proximities for each building in the dataset. Proximities include 150 meters, 250 meters, and 500 meters.

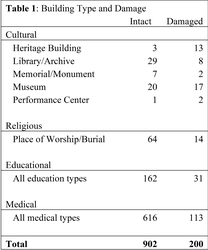

Building type: In total, 61,543 buildings are identified. To assess whether protected civilian buildings were damaged disproportionately, we identified whether a building was one of four classes: Cultural, Religious, Educational, or Medical. Open Street Maps was used to identify Educational and Medical Buildings. Data curated by the Virginia Museum of Natural History was used to identify Cultural and Religious buildings.Bassett, H. F., Koropeckyj, D. V., Welsh, W., Averyt, K., Hanson, K., Aronson, J., Cil, D., Wegener, C., and Daniels, B. I. (2022). “Ukrainian cultural heritage potential impact summary (09 May 2022).” Virginia Museum of Natural History, Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab; and Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative. Available at: https://hub.conflictobservatory.org/portal/sharing/rest/content/items/6b7c5f0225f64d82b33c2abf63fe72f5/data.[7] Our sample includes 102 Cultural, 78 Religious, 193 Educational, and 729 Medical buildings. The remaining 60,441 buildings, which includes residential, commercial, and industrial buildings, are classified as “other.” Table 1 provides a summary of the building types and damage observed in this study.

Building footprint, city center, and proximity to roads: Data on the size of a building’s footprint was obtained from multiple sources, including AI-derived footprints from high-resolution imagery (OpenStreetMap, Microsoft Bing Maps Machine Learning, Geofabrik) and manual delineation by analysts. Buildings with larger footprints may have an increased likelihood of experiencing collateral damage. For instance, errant fire is more likely to hit a larger building than a smaller building. City centers are identified based on the centroid of each ADM4 polygon derived from OpenStreetMap. Data on proximity to roads was derived from OpenStreetMap. The distance between a building and the closest primary (e.g., highways of all types) and secondary (e.g., main roads in a city) road is calculated. Proximity to roads may explain damage. Combatants, for example, may utilize larger roads such as highways, to move their forces, which increases the likelihood that a nearby building is damaged.

Armed conflict: Data on armed conflict events is obtained from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project.Raleigh, C., Linke, A., Hegre, H., and Karlsen, J. (2010). “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special data feature,” Journal of Peace Research, 47(5): pp. 651–660.[8] The precision of the conflict events in ACLED is limited to the city and, in some cases, the neighborhood. Because of uncertainty in the exact location of a conflict event, which makes it impossible to determine the proximity of conflict to a specific building, we aggregate event counts to the city-week.For a discussion of how the data is aggregated, see Aronson, J., Cil, D., Marx, A., and Pound, F. (2022). “Population displacement and return in Ukraine,” Conflict Observatory, 14 October. Available at: https://hub.conflictobservatory.org/portal/sharing/rest/content/items/26588fced1984eef91d189c78ac9e675/data.[9] Each city-week is divided into one of four categories based on who initiated attacks: none (no conflict was recorded), Ukraine-initiated, Russia-initiated, and both-initiated. Areas with just Ukraine-initiated attacks are likely to be in Russian territory and represent the use of Ukrainian indirect strikes. Similarly, areas with just Russia-initiated attacks are likely to be in Ukrainian territory and represent the use of Russian indirect strikes. Areas where both sides are initiating attacks represent locations on the front line where combatants are using direct-fire weapons to fight each other and contest territory within visual range.

Territorial control: To identify territorial control, we draw on the Violent Incident Information from News Articles dataset.Zhukov, Y. (2022). VIINA: Violent incident information from news articles on the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies.[10] This data is available by tessellated polygon in Ukraine, which roughly conforms to an ADM4.Because data on conflict and control is aggregated to the city, we are unable to use various distance decay metrics to account for the distance between conflict/control and a building.[11] Because tessellation occurs around a city center point, a city may have multiple polygons when several ADM4s are near to each other. The variable records the portion of territorial control in a city-week that Russia has (the inverse indicates the portion of control that Ukraine has). Locations without any Russian control are identified as Ukrainian-held. Cities without any Ukrainian control are identified as Russian-held. We further divide Russian control into areas that Russia held prior to the start of the full-scale invasion and areas that Russia captured after the full-scale invasion. The conflict dynamics in areas captured by the so-called People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk might be different than in areas captured by Russian forces. All other locations (locations with partial control by both combatants) are identified as contested.

Examples of Observed Building Damage

To show the types of buildings examined and the types of damage observed using satellite imagery, we focus on three illustrative examples in Ukraine: (1) the Martynov Palace of Culture in Bakhmut, (2) the Mariupol Drama Theatre in Mariupol, and (3) the Shakhtar Cinema in Horlivka. The first example of the type of damage that our data records is the destruction inflicted on the Marynov Palace of Culture in Bakhmut. Substantial damage can be seen on satellite imagery by 6 March 2023, which occurred as the result of shelling by Russia’s forces (see Figure 1).PBS. (2022). “Martynov Palace of Culture shelled by Russians,” PBS, 8 September. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/interactive/ap-russia-war-crimes-ukraine/?facets=%7CCultural+or+Religious+Site%7C.[12] The Palace of Culture, named after Yevgeniy Martynov (1948–1990), a Soviet pop singer and composer, is a nearly century-old building covered in brick and reinforced concrete that includes a theater hall in central Bakhmut.Farago, J., Kerr, S., Tiefenthäler, A., and Willis, H. (2022). “A culture in the cross hairs,” The New York Times, 19 December. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/12/19/arts/design/ukraine-cultural-heritage-war-impacts.html[13] This building is representative of the type of building that we argue has been damaged disproportionately in Ukraine: locally prominent, made of durable materials, possibly occupied by emergency services (or military forces), and in an area over which combatants seek to establish territorial control.Zhukova, N. (2022). “In Bakhmut, the oldest palace of culture is on fire,” Free Radio, 9 September. Available at: https://freeradio.com.ua/v-bakhmuti-palaie-naistarishyi-palats-kultury-poshkodzhena-budivlia-dsns-ta-nemaie-vody-naslidky-obstriliv-na-8-veresnia-foto-video/.[14]

The second example of the type of damage that our data records is the Mariupol Drama Theatre (see Figure 2). The Mariupol Drama Theater, also known as the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theatre, was built in 1878 in central Mariupol. The current building, a large stone building with a red roof, white pillars, and classical frieze, was constructed in 1959 and was granted the status of Donetsk State Theater. This building, infamously, was destroyed by missile strikes conducted by Russia’s armed forces.Hinnant, L, Chernov, M., and Stepanenko, J. (2022). “AP evidence points to 600 dead in Mariupol theater airstrike,” AP, 4 May. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/Russia-ukraine-war-mariupol-theater-c321a196fbd568899841b506afcac7a1.[15] The building is also prominent, largely stands alone, and likely had substantial traffic in and around the building. The building additionally served as a humanitarian hub that may have been viewed by Russia’s forces as helping to sustain the defenders’ local will to fight by providing support to trapped civilians and/or military forces.Trew, B. (2022). “Deadly airstrike on Mariupol theatre a ‘clear war crime’, Amnesty inquiry finds,” Independent 30 June. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/ukraine-mariupol-airstike-russia-latest-b2112431.html.[16] Targeting may have occurred because the building was seen as providing defensive utility, civilian traffic was confused for military activity, or destruction was intended to create refugee flows that pose logistic difficulties for the defenders. As such, the destruction of this building is also consistent with the reasoning advanced in this paper.

The third example of the type of damage that our data records is the Shakhtar Cinema in Horlivka (see Figure 3). The Shakhtar Cinema is a venue for cultural events in Horlivka. Originally built in 1951 as a movie theater, it includes a large hall with Stalin-era decoration.Bartlett, E. K. (2022). “Using American HIMARs, Ukraine shelled an historic cultural building in Gorlovka,” YouTube, 19 November. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZeH6nwM4taQ; Khorishko, V. (2017). “Horlivka, Donetsk region,” Travellerspoint, 22 April. Available at: https://horlivka.travellerspoint.com.[17] Like the theater in Mariupol, the Shakhtar Cinema is a locally prominent building that is both taller and more likely to be more robustly constructed than neighboring buildings. The location is also centrally positioned in Horlivka. These characteristics may have made the location appealing to attacking and defending military forces, exposing the building to a heightened risk of damage. The characteristics of this building are also consistent with the patterns of building damage uncovered in our statistical analysis.

Results for Donetsk Oblast

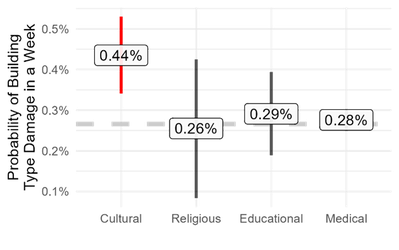

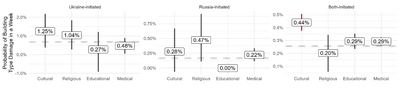

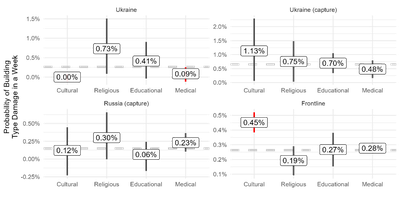

Three model specifications are utilized to identify where and why damage to a building type occurs. The main model, shown in Figure 4, shows the effect of building type on the occurrence of damage using the full sample of Donetsk Oblast. This allows us to assess whether a building type experiences disproportionate damage on average across all cities in Donetsk Oblast. We run two additional models that interact the main variable with a measure of conflict, Figure 5, and a measure of Russia’s territorial control, Figure 6. These two measures capture a similar idea: identifying which areas Russia and Ukraine are attacking or contesting directly and which areas may instead see indirect strikes by just one combatant. All models are robust to the inclusion or exclusion of various area weighting schemes including inverse area weights, dropping linear time trends, dropping all control variables, and using different distance measures for nearby damaged buildings. Note also that our results are robust to the use of a simple two-way fixed effects model without any control variables. All robustness test results are available upon request. Full statistical results for the models used to create Figures 4–6 can be found in Appendix Table A1.

Deliberate Targeting

Based on quantitative analysis of damage to buildings in Donetsk Oblast that occurred between 24 February 2022 and 24 February 2023, cultural buildings have a greater probability of experiencing damage than do religious, educational, or medical buildings (see Figure 4). Cultural buildings include heritage buildings, libraries, archives, memorials/monuments, museums, and performance centers. The X-axis indicates the building type. The Y-axis shows the probability that a building type is damaged in a week. The label shows the point estimate while the vertical bars show the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference in the probability that a building type will be damaged compared to the “baseline” probability (a “first difference”). The horizontal dashed gray line shows the baseline probability that a building type other than the four listed above is damaged. If the CI does not cross the dashed gray line, the effect is statistically significant. Only cultural buildings, which have a 0.44% chance of experiencing damage in a week, are statistically different from other building types. By comparison, the probability of damage to another building type is 0.27%. More directly, this means that cultural buildings are the only building type that is observed to be deliberately targeted. While this probability appears small, it accumulates over time. Within the first year of war, for instance, each of the 102 cultural buildings in our sample had a 20.4% chance of experiencing damage compared to a 13.0–14.1% chance for a building of another type. An example helps to demonstrate the magnitude of damage. In a city with 10 cultural buildings, we would expect that two of these buildings would be damaged in the first year of conflict.

Our analysis accounts for other common explanations for the occurrence of damage, such as the size of the building’s footprint. If cultural buildings are larger on average, they might also be damaged at a higher rate due to armed activity. Because we control for this variable, we know that cultural buildings are damaged at a higher rate regardless of their size. Similarly, presence in a location within a city that is more likely to experience fighting and collateral damage due to proximity to other targets, such as roads, does not explain why cultural buildings exhibit disproportionate damage. It is important to note that we examine large-scale damage observable by satellite, such as damage to the roof. Therefore, when we use the word “damage,” we mean large-scale damage that might result from artillery, missile strike, or tank fire. Smaller-scale damage, such as broken windows or bullet holes, is not included. It is possible that other building types also experience small-scale damage at a higher rate.

To better understand why buildings of a specific type are more likely to be damaged, we analyze building destruction in areas that differ in important conflict dynamics. Specifically, we look at areas that differ in terms of who initiated conflict events (Russia, Ukraine, or both), who had territorial control (Russia, Ukraine, or contested by both), and whether this territory was (re)captured or controlled since the start of the war. These additional analyses produce consistent findings for both armed conflict and territorial control.Ongoing conflict and extent of territorial control are measured using different data sources and conceptually capture different yet closely related phenomena to armed contestation. For example, see Kalyvas, S. (2006). The logic of violence in civil war. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. We use two separate models to avoid concerns about multicollinearity, one including conflict and the other including territorial control variable.[18] Cultural buildings are more likely to experience damage during weeks when there is active armed contestation in the city where a building is located. Areas under armed contestation are defined as areas where both sides initiate conflict events or areas where neither side can establish territorial control. Figures 5 and 6 visualize these results for locations with ongoing armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine (see Figure 5)We examine only locations where at least one combatant, Russia or Ukraine, initiated an attack.[19] and for locations with varying territorial control (see Figure 6).

The effect for cultural buildings in frontline locations is above the gray dashed line. In a week, there is a 0.45% chance that a cultural building is damaged. Over a year, more than one in five cultural buildings (21.1%) in frontline locations are likely to be damaged compared to 12.6% for other building types. No building type suffers damage at a disproportionate rate in other locations: where no fighting is occurring, where fighting is initiated only by one side but not both, and where one side has complete control. This indicates that there is a “heterogenous treatment effect.” While analysis of the full sample identifies a higher rate of damage to cultural buildings in all cities, subsequent analysis shows that the effect only occurs in locations with ongoing, direct fighting between Russia and Ukraine. This finding should be interpreted as the main result of the paper.

The results shown in Figures 5 and Figure 6 also provide evidence that medical buildings are more likely to experience damage in actively contested areas. (The effect is positive but not significant in locations of incomplete territorial control.) In a week, each medical building has a 0.29% chance of being damaged. Over a year, this equates to damage to one in six medical buildings (14.2%) in contested areas. Despite the smaller effect compared to cultural buildings, this is still an important finding—medical buildings, which are crucial for civilians and combatants, are disproportionately damaged and destroyed during ongoing fighting.

We also find two negative and significant effects in areas held by Ukraine since the start of the war. Cultural and Medical buildings are both less likely than other building types to be damaged. When attacks do occur, they occur because Russia has used indirect-fire weapons such as long-range artillery, suicide drones, or missiles. This finding suggests that Russia may be trying to avoid deliberately striking targets such as cultural sites and medical facilities that lack any local military utility and are likely to lead to more international condemnation if damaged. This is consistent with Russia’s use of indirect weapons to prioritize targeting of strategic economic or military assets such as energy or transportation infrastructure.Meilhan, P., and Roth, R. (2022). “Ukrainian military says 18 Russian cruise missiles destroyed amid attacks on energy infrastructure,” CNN, 22 October. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/10/22/europe/russia-ukraine-war-intl-hnk/index.html.[20] An important caveat is that these patterns may differ if locations such as Kyiv or cities further west were included in the sample. As a result, this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Explanation for Deliberate Targeting

Our results are consistent with a main explanation for why damage occurs: Cultural buildings (and to a lesser extent medical buildings) suffer damage at a higher rate than expected due to the role that they likely play in active military contestation.

There are several characteristics of cultural buildings that may influence their role in local combat. Cultural buildings, for example, may be constructed of sturdier material such as stone, or may be taller than other nearby buildings. When fighting in a city, combatants are advantaged by emplacing themselves in positions that are protected from enemy fire and that provide an advantage for spotting opposing forces. These characteristics that increase a combatant’s desire to occupy or fight in a specific type of building also make it more likely that the same type of building will be targeted by enemy attack.This characteristic of historic buildings has led to their destruction many times in history. Examples include German use of Monte Cassino in World War Two (Gregg, C. (2021). “The destruction of Monte Cassino,” The National WWII Museum, 15 January. Available at: https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/destruction-of-monte-cassino-1944) and the Islamic State use of ruins and castles in Syria (Maclean, R. (2017). “Desecrated but still majestic: inside Palmyra after second ISIS occupation,” The Guardian, 9 March. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/09/inside-palmyra-syria-after-second-isis-islamic-state-occupation).[21] Medical buildings are not as likely to provide commanding terrain but do directly support a combatant’s ability to fight in a city by providing treatment to wounded personnel, which helps to sustain a combatant’s willingness to keep fighting.For a discussion of collective action, see Fog, A. (2019). “Collective action problems in offensive and defensive warfare,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 42(122): e122; Lehman, T. C., and Zhukov, Y. (2019). “Until the bitter end? the diffusion of surrender across battles,” International Organization 73(1): pp. 133–169.[22] Anecdotally, several of the cultural buildings that were damaged also had humanitarian infrastructure co-located.For example, the Mariupol Drama Theatre had the main field kitchen serving individuals trapped in the city. See Hinnant, L., Chernov, M., and Stepanenko, V. (2022.) “AP evidence points to 600 dead in Mariupol theater airstrike,” AP News, 4 May. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-war-mariupol-theater-c321a196fbd568899841b506afcac7a1. Similarly, the Palace of Culture in Chasiv Yar was also a local aid distribution and medical center that was reportedly struck by Russian attacks. See: “Russians destroy Palace of Culture used to provide medical assistance,” Ukrainska Pravda, 23 July. Available at: https://sports.yahoo.com/chasiv-yar-russians-destroy-palace-094404513.html.[23] This humanitarian infrastructure may have also helped to sustain the willingness of Ukrainian forces, who have demonstrated greater concern for civilian wellbeing, to continue to defend a location. The targeting of civilians with coercion to undermine an opponent’s will or ability to fight has long been used as a military strategy to varying effect.Zhukov, Y. (2023). “Repression works (just not in moderation),” Comparative Political Studies (forthcoming).[24]

We reach this conclusion about the reason cultural (and secondarily medical) buildings are damaged at a rate disproportional to the damage experienced by other building types based on several findings. First, damage occurs at a disproportionate rate only in cities and weeks where conflict initiated by both Ukraine and Russia is ongoing. Damage does not occur at a disproportionate rate in cities where only one combatant initiates attacks (e.g., long-range artillery or missile strikes) or in cities where a single combatant has dominant control (e.g., Mariupol was under Russia’s complete control from June 2022 onward). In other words, these building types are damaged due to characteristics that matter during direct and ongoing armed conflict.The effect for educational buildings in contested locations is also positive but not statistically significant (Figure 3). Certain educational buildings, such as schools, may also have many of the relevant characteristics of cultural buildings such as sturdy construction. Additional analysis with a larger sample or decomposition of the “educational” category to identify sturdier buildings may yield different results.[25] Any explanation of disproportionate damage needs to identify why a building type is targeted during but not outside of a battle. This helps to exclude other possible explanations for observed damage based on ideological reasons, such as targeting Ukrainian identity. Instead, these results suggest that the reason of disproportionate damage to cultural and medical buildings is to undermine Ukrainian will and/or ability to fight in a specific ongoing battle.

Second, the analysis accounts for key reasons why buildings might suffer unintentional damage, including centrality in a city, proximity to major roads that combatants might use to move forces and supplies, the density of other nearby buildings, and the number of other nearby same- and different-type buildings that were damaged in the prior week. Because we account for all these reasons, it is unlikely that cultural (and medical) buildings are damaged at a higher rate in contested locations due to collateral damage. In other words, the damage we identify does not occur because cultural and medical buildings happen to be in locations within a city where fighting naturally occurs or locations near to other buildings (e.g., train stations) that are more likely to be a military target. Excluding explanations for collateral damage does not guarantee that targeting was deliberate, but it does make it much more likely.

Third, the analysis accounts for the size of buildings based on the area of their footprint. If military activity such as artillery fire were randomly distributed throughout a city, larger buildings would naturally be damaged at a higher rate than smaller buildings. More area, in other words, means more exposure to explosions and errant strikes. Our findings hold after controlling for building area, suggesting that area does not explain disproportionate damage. This helps to exclude the explanation that cultural and medical buildings are damaged at a higher rate because they happen to be larger buildings on average. (It should also be noted that our analysis examines the rate of damage, so the number of buildings of a particular type also does not bias the findings.)

Fourth, the disproportionate damage that occurs to cultural but not religious buildings provides evidence that buildings are not being targeted because of the religious identity or ideology that they represent.We do not have data on the affiliation of religious buildings (Russia or Ukraine). Incorporation of this information may affect our findings.[26] If, for example, Russia was seeking to destroy buildings for ideological reasons, they would also target religious buildingsSubsequent analysis will seek to disaggregate religious buildings based on whether they affiliate with the Moscow Patriarchate. This will produce further evidence of whether or not targeting of civilian infrastructure was ideological in nature.[27]—like the Islamic State’s targeting of non-Sunni sites in Iraq and Syria.See, for example, Clapperton, M., Jones, D. M., and Smith, M. L. R. (2017). “Iconoclasm and strategic thought: Islamic State and cultural heritage in Iraq and Syria,” International Affairs 93(5): 1205–1231.[28] This is further supported by the decreased damage to cultural and medical buildings observed in territory held by Ukraine since the start of the war. In addition, damage also occurs at a disproportionate rate for medical buildings, which is another building type most likely to have local military value in ongoing armed conflict (as noted above, some cultural buildings also contained medical/humanitarian support). Together, this suggests that building types are not systematically targeted for ideological reasons, which helps to exclude ideology-based explanations for the occurrence of damage.

Several examples illustrate our theorized mechanisms and provide support for our empirical analysis. In the battle for Sviatohirsk in northern Donetsk province in June 2022, Ukrainian forces fought on or around the grounds of the Sviatohirsk Cave Monastery. The Monastery provided shelter to civilians, but, more importantly, was a tall and sturdy building that provided overwatch of the only bridge into the town and served as a critical defense position for Ukrainian forces. As the battle unfolded Russian fire damaged the building. Ukrainian artillery also likely damaged the structure when Russian forces operating in the vicinity of the Monastery were bombarded. As the military administrator of the town notes, damage occurred because both sides fought for control of the building: “the enemy was held off here, when the Ukrainians kept the Russians from fording the river.”Gibbons-Neff, T., and Yermak, N. (2022). “A Gray Area of Loyalties Splinters a Liberated Ukrainian Town,” New York Times, 10 December. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/08/world/europe/ukraine-russia-loyalty-sviatohirsk.html.[29] Russian forces also attacked hospitals due to their perceived role in sustaining Ukrainian resistance. In Kharkiv, for instance, Ukrainian forces at the Military Medical Center were attacked just a week into the invasion.Clark, M., Barros, G., and Stepanenko, K. (2022). “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, March 2,” Institute for the Study of War, 2 March. Available at: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-2.[30] Correctly or incorrectly, the Russians believed that Ukrainian troops were fighting in or being supported by the medical facility. In Mykolaiv, a hospital was struck by missile fire for the same reason. This justification was laid out by a pro-Russian Telegram source: “The civilian hospital was converted into a military hospital, where they tried to get the wounded evacuated from the front back on their feet.”Rybar. (2022). “About a strike on a military hospital in Mykolaiv,” 4 September. Available at: https://t.me/rybar/38193.[31] These justifications for striking Cultural and Medical buildings does not necessarily mean that they are legitimate targets according to international law.

In sum, our process allows us to say with some confidence that cultural, and to a lesser extent medical, buildings were deliberately targeted by combatants in cities in Donetsk Oblast where both Russia and Ukraine have been actively engaged in direct military contestation. The statistical analysis can rule out several common alternative explanations for disproportionate damage. For example, the analysis suggests that disproportionate damage did NOT occur because these building types are present in cities that experienced more widespread or intense fighting, or because these building types are bigger on average. The analysis can also rule out several explanations related to where in a city a building is located. Disproportionate damage did NOT occur because these building types are in areas within a city where fighting is more likely to occur, where both sides used heavier ordnance, or are near to other buildings that are more likely to be damaged (collateral).

Limitations of Methodological Approach

There are several limitations of the process and results presented. Use of statistical analysis allows us to identify patterns of damage, which we link to deliberate combatant policies. This approach, however, is not appropriate for determining if a combatant targeted any single building. In addition, our analysis examines only a single oblast. Results may change if we examine all buildings in Ukraine or include cities, such as Kyiv, where Russia has targeted civilian infrastructure outside of actively contested areas. This difference in results would be due to variation in combatant goals and strategies across Ukraine. However, the scale and scope of conflict in Donetsk is comparable to other heavily contested oblasts such as Kherson and Kharkiv. Consequently, we expect that the findings in this paper are likely to apply to other areas that experienced similar large-scale attritional warfare. Lastly, the estimand in our study is the rate of damage by building type. We do not seek to, nor does our estimator produce results for, the count of damaged buildings of a specific type, although it would be possible to use the estimated rate to predict the number of buildings of a type that are damaged.

There are also a few limitations associated with the data generation process. As we have noted, our data records only damage that can be identified through satellite imagery. Small-scale damage such as bullet holes or damage that occurs inside a building are not detectable by satellite. Satellite-observable damage is more likely to occur when high-explosive weapons such as artillery or missiles are used and when these weapon systems are directed at the building. This is unlikely to bias our results, as we seek to exclude accidental damage and damage that does not result from military actions initiated by the armed forces of Russia or Ukraine. Finally, the minimum buildings size included in our data is 370 square meters (~4,000 square feet), which means our results only apply for buildings of this size or larger. Despite this, it is likely that our findings would apply to smaller buildings. The main reason why our findings would not apply is if smaller buildings had systematic differences along critical dimensions from large buildings (aside, of course, from size, which is controlled for). For instance, if small cultural buildings were not as robustly constructed as large cultural buildings on average, our findings would not apply.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a new process for identifying the deliberate targeting of buildings during armed conflict. This process involves the use of AI to identify building damage in satellite imagery combined with quantitative causal methods focused on the use of statistical analysis to eliminate observed and unobserved explanations for the correlation of building type and the occurrence of damage other than deliberate targeting. This method is applied to the case of Donetsk Oblast in the first year of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, February 2022–February 2023. Results demonstrate that of the building types examined—cultural, religious, educational, medical, and other—only cultural and, secondarily, medical buildings are deliberately targeted and that targeting occurs only in locations and periods where both Russia and Ukraine have armed forces engaged in direct battle with each other. Building types are not damaged at a higher rate in other locations. The evidence assembled is consistent with deliberate targeting by combatants due to the perception that cultural and medical buildings affect the local ability or will of opponents to keep fighting. These buildings, in other words, affect the dynamics of local conflict and are targeted for this reason. This evidence is based on the type of building damaged, where and when damage was observed, and the use of statistical analysis to eliminate alternative explanations.

Below, we discuss the policy implications of these findings and next steps in this research agenda.

Policy Implications

Our main finding is that building types are deliberately targeted at a different rate because of the role that they play in local as opposed to national conflict dynamics. When seeking to justify damage to domestic or international audiences, this military reasoning is likely to be front and center. Unless there is a real threat of reciprocation, international law is unlikely to have much impact on this type of behavior because combatants view it as important to wartime outcomes.Morrow, J. D. (2007). “When do states follow the laws of war,” American Political Science Review 101(3): 559–572.[32] For instance, Russia’s behavior may change if Ukraine can credibly threaten to destroy important buildings in Russia in response to Russia’s deliberate targeting of buildings in Ukraine. A second implication is that the characteristics of a building that make it useful for military occupation and the presence of support institutions (especially “dual-use” services/institutions such as hospitals that can provide medical care to civilians and soldiers) increase the chance that a building will be deliberately targeted. Civilians seeking shelter from violence should take this into account. Humanitarian institutions should also be aware of how combatants perceive their role in conflict. While we do not test this directly, this type of targeting is likely to be especially problematic in long, grinding battles where one side has become militarily frustrated and is seeking alternative means to coerce an opponent.See, for example, Downes, A. B. (2007). “Restraint or propellant? Democracy and civilian fatalities in interstate wars,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51(6): 872–904; Downes, A. B. (2006). “Desperate times, desperate measures: the causes of civilian victimization in war,” International Security 30(4): 152–195.[33]

The data developed and the results of the quantitative analysis can also be used to improve decision-making and forecasting in the following ways:

(1) The identification of the extent of destruction in a location based on the portion of buildings damaged can improve planning for post-conflict reconstruction.

(2) The examination of the likely impact of conflict (or a natural disaster) on buildings can help provide interested third parties with information about civilian access to an adequate standard of living in a location. Understanding which types of buildings are destroyed and the extent of this damage provides policymakers with information that improves their ability to allocate humanitarian resources or effort.

(3) The determination of the type and extent of buildings damaged can enable broad determinations about whether combatants are pursuing maneuver or attrition strategies, which provides information about how a combatant operates and what it is seeking to achieve. In addition, the types of deliberately targeted buildings provide information about combatant strategy, including how combatants view the link between the use of coercive activity and the accomplishment of local goals. For instance, whether a combatant uses a strategy of denial or punishment can be identified.Pape, R. A. (1996). Bombing to win: air power and coercion in war. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.[34] A better understanding of an opponent’s local strategy can lead to a better military response.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrew Marx provided data, assisted with questions about data fidelity and collection details, and consulted to improve discussions about the data cited.

Graphs

Figure 1: Satellite images of Martynov Palace of Culture, Bakhmut, Ukraine.

Source: Left: WV03_VNIR, Acquisition date: 2022-05-08, Resolution: 40 cm, Copyright: ©2022 Maxar; Right: WV03_VNIR, Acquisition date: 2023-03-06, Resolution: 36 cm, Copyright: ©2023 Maxar

Figure 2: Satellite images of Mariupol Drama Theater, Mariupol, Ukraine.

Source: Left: GE01, Acquisition date: 2022-03-14, Resolution: 48 cm, Copyright: ©2022 Maxar; Right: WV03_VNIR, Acquisition date: 2022-03-29, Resolution: 38 cm, Copyright: ©2022 Maxar

Figure 3: Satellite images of Shakhtar Cinema, Horlivka, Ukraine.

Source: Left: WV02, Acquisition date: 2022-11-08, Resolution: 48 cm, Copyright: ©2022 Maxar; Right: WV03_VNIR, Acquisition date: 2022-11-29, Resolution: 38 cm, Copyright: ©2022 Maxar

Figure 6: Damage in Frontline Locations (Incomplete Territorial Control)

Note: In locations with back-and-forth fighting between Russia and Ukraine (“Both-initiated” and “Frontline”) Cultural and Medical buildings are more likely than other building types to be damaged. In areas where Ukraine has territorial control, Medical buildings are less likely than other building types to be damaged.

Source: Original work by authors.

Look Ahead

There are two next steps for future research. First, we intend to apply our process and statistical methodology to more oblasts in Ukraine and to other cases. Analyzing additional data will provide further insight on the perpetrator of deliberate targeting and the reason why deliberate targeting occurred. Second, we plan to incorporate additional data on industrial buildings, powerplants, and energy and transportation infrastructure. These additional building types are currently included in the “other” building category. Power and transportation infrastructure are known strategic and tactical targets for Russia's armed forces. Additional analysis of expanded data may identify deliberate targeting of energy and transportation buildings, which would provide additional insight into who targeted distinct types of buildings in Ukraine, why deliberate targeting occurred, and the strategy Russia intends to use to try to bring Ukraine to the bargaining table.

Things to Watch

- expanding building types to include industry, energy, and transportation categories